Are They Associated with Precocious Puberty Too? Daniëlle C.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

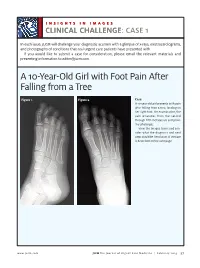

A 10-Year-Old Girl with Foot Pain After Falling from a Tree

INSIGHTS IN IMAGES CLINICAL CHALLENGECHALLENGE: CASE 1 In each issue, JUCM will challenge your diagnostic acumen with a glimpse of x-rays, electrocardiograms, and photographs of conditions that real urgent care patients have presented with. If you would like to submit a case for consideration, please email the relevant materials and presenting information to [email protected]. A 10-Year-Old Girl with Foot Pain After Falling from a Tree Figure 1. Figure 2. Case A 10-year-old girl presents with pain after falling from a tree, landing on her right foot. On examination, the pain emanates from the second through fifth metatarsals and proxi- mal phalanges. View the images taken and con- sider what the diagnosis and next steps would be. Resolution of the case is described on the next page. www.jucm.com JUCM The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine | February 2019 37 INSIGHTS IN IMAGES: CLINICAL CHALLENGE THE RESOLUTION Figure 1. Mediastinal air Figure 1. Differential Diagnosis Pearls for Urgent Care Management and Ⅲ Fracture of the distal fourth metatarsal Considerations for Transfer Ⅲ Plantar plate disruption Ⅲ Emergent transfer should be considered with associated neu- Ⅲ Sesamoiditis rologic deficit, compartment syndrome, open fracture, or vas- Ⅲ Turf toe cular compromise Ⅲ Referral to an orthopedist is warranted in the case of an in- Diagnosis tra-articular fracture, or with Lisfranc ligament injury or ten- Angulation of the distal fourth metatarsal metaphyseal cortex derness over the Lisfranc ligament and hairline lucency consistent with fracture. Acknowledgment: Images courtesy of Teleradiology Associates. Learnings/What to Look for Ⅲ Proximal metatarsal fractures are most often caused by crush- ing or direct blows Ⅲ In athletes, an axial load placed on a plantar-flexed foot should raise suspicion of a Lisfranc injury 38 JUCM The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine | February 2019 www.jucm.com INSIGHTS IN IMAGES CLINICAL CHALLENGE: CASE 2 A 55-Year-Old Man with 3 Hours of Epigastric Pain 55 years PR 249 QRSD 90 QT 471 QTc 425 AXES P 64 QRS -35 T 30 Figure 1. -

Genetic Mechanisms of Disease in Children: a New Look

Genetic Mechanisms of Disease in Children: A New Look Laurie Demmer, MD Tufts Medical Center and the Floating Hospital for Children Boston, MA Traditionally genetic disorders have been linked to the ‘one gene-one protein-one disease’ hypothesis. However recent advances in the field of molecular biology and biotechnology have afforded us the opportunity to greatly expand our knowledge of genetics, and we now know that the mechanisms of inherited disorders are often significantly more complex, and consequently, much more intriguing, than originally thought. Classical mendelian disorders with relatively simple genetic mechanisms do exist, but turn out to be far more rare than originally thought. All patients with sickle cell disease for example, carry the same A-to-T point mutation in the sixth codon of the beta globin gene. This results in a glutamate to valine substitution which changes the shape and the function of the globin molecule in a predictable way. Similarly, all patients with achondroplasia have a single base pair substitution at nucleotide #1138 of the FGFR3 gene. On the other hand, another common inherited disorder, cystic fibrosis, is known to result from changes in a specific transmembrane receptor (CFTR), but over 1000 different disease-causing mutations have been reported in this single gene. Since most commercial labs only test for between 23-100 different mutations, interpreting CFTR mutation testing is significantly complicated by the known risk of false negative results. Many examples of complex, or non-Mendelian, inheritance are now known to exist and include disorders of trinucleotide repeats, errors in imprinting, and gene dosage effects. -

Background Briefing Document from the Consortium of Sponsors for The

BRIEFING BOOK FOR Pediatric Advisory Committee (PAC) Prepared by Alan Rogol, M.D., Ph.D. Prepared for Consortium of Sponsors Meeting Date: April 8th, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. LIST OF TABLES ...........................................................................................................................4 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND FOR THE MEETING .............................6 1.1. INDICATION AND USAGE .......................................................................................6 2. SPONSOR CONSORTIUM PARTICIPANTS ............................................................6 2.1. TIMELINE FOR SPONSOR ENGAGEMENT FOR PEDIATRIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE (PAC): ............................................................................6 3. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE .........................................................................7 3.1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................7 3.2. PHYSICAL CHANGES OF PUBERTY ......................................................................7 3.2.1. Boys ..............................................................................................................................7 3.2.2. Growth and Pubertal Development ..............................................................................8 3.3. AGE AT ONSET OF PUBERTY.................................................................................9 3.4. -

Segmental Overvekst Og Vaskulærmalformasjoner V02

2/1/2021 Segmental overvekst og vaskulærmalformasjoner v02 Avdeling for medisinsk genetikk Segmental overvekst og vaskulærmalformasjoner Genpanel, versjon v02 * Enkelte genomiske regioner har lav eller ingen sekvensdekning ved eksomsekvensering. Dette skyldes at de har stor likhet med andre områder i genomet, slik at spesifikk gjenkjennelse av disse områdene og påvisning av varianter i disse områdene, blir vanskelig og upålitelig. Disse genetiske regionene har vi identifisert ved å benytte USCS segmental duplication hvor områder større enn 1 kb og ≥90% likhet med andre regioner i genomet, gjenkjennes (https://genome.ucsc.edu). Vi gjør oppmerksom på at ved identifiseringav ekson oppstrøms for startkodon kan eksonnummereringen endres uten at transkript ID endres. Avdelingens websider har en full oversikt over områder som er affisert av segmentale duplikasjoner. ** Transkriptets kodende ekson. Ekson Gen Gen affisert (HGNC (HGNC Transkript Ekson** Fenotype av symbol) ID) segdup* ACVRL1 175 NM_000020.3 2-10 Telangiectasia, hereditary hemorrhagic, type 2 OMIM ADAMTS3 219 NM_014243.3 1-22 Hennekam lymphangiectasia- lymphedema syndrome 3 OMIM AKT1 391 NM_005163.2 2-14 Cowden syndrome 6 OMIM Proteus syndrome, somatic OMIM AKT2 392 NM_001626.6 2-14 Diabetes mellitus, type II OMIM Hypoinsulinemic hypoglycemia with hemihypertrophy OMIM AKT3 393 NM_005465.7 2-14 Megalencephaly-polymicrogyria- polydactyly-hydrocephalus syndrome 2 OMIM file:///data/SegOv_v02-web.html 1/7 2/1/2021 Segmental overvekst og vaskulærmalformasjoner v02 Ekson Gen Gen affisert (HGNC (HGNC -

Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty Melissa Schoelwer, MD and Erica A Eugster, MD Section of Pediatric Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana Send correspondence to: 705 Riley Hospital Drive, Room 5960 Indianapolis, IN 46202 Phone: 317-944-3889 Fax: 317-944-3882 Email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Schoelwer, M., & Eugster, E. A. (2016). Treatment of Peripheral Precocious Puberty. In Puberty from Bench to Clinic (Vol. 29, pp. 230-239). Karger Publishers. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000438895 Peripheral Precocious Puberty Abstract There are many etiologies of peripheral precocious puberty (PPP) with diverse manifestations resulting from exposure to androgens, estrogens, or both. The clinical presentation depends on the underlying process and may be acute or gradual. The primary goals of therapy are to halt pubertal development and restore sex steroids to prepubertal values. Attenuation of linear growth velocity and rate of skeletal maturation in order to maximize height potential are additional considerations for many patients. McCune-Albright syndrome (MAS) and Familial Male-Limited Precocious Puberty (FMPP) represent rare causes of PPP that arise from activating mutations in GNAS1 and the LH receptor gene, respectively. Several different therapeutic approaches have been investigated for both conditions with variable success. Experience to date suggests that the ideal therapy for precocious puberty secondary to MAS in girls remains elusive. In contrast, while the number of treated patients remains small, several successful therapeutic options for FMPP are available. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

Precocious Puberty Children with Spina Bi�Da and Hydrocephalus May Start Puberty Earlier Than Their Peers

SBA National Resource Center: 800-621-3141 Precocious Puberty Children with Spina Bida and hydrocephalus may start puberty earlier than their peers. What is Puberty? If major breast development starts before age 8, it is considered early. (Sometimes girls will have some Puberty refers to normal body changes that lead to breast development, with no other signs of puberty. maturity and the ability to have children. Normal puberty This isolated change may be normal.) begins between ages 8 and 12 in girls and between 9 and 14 in boys. Hormones made in the brain control the timing and sequence of puberty. These hormones What are the stages of normal puberty in boys? stimulate other parts of the body to make sex hormones. The usual sequence in boys is: The sex hormones, especially estrogen in girls and testosterone in boys, cause sexual maturation. • The testicles grow larger. • The penis grows larger. What are the stages of normal puberty in girls? • Pubic hair grows. The physical changes seen in puberty are labeled by “Tanner staging.” Stage 1 is child-like (before puberty) • There is a growth spurt.rt. and stage 5 is full maturity. The usual sequence in girls is: • Other body hair grows.s. • Breasts start to develop. If boys show major developmentelopment • Hips widen and a there is a growth spurt that usually before age 9, it is considereddered lasts about three to four years. early. Early puberty in girls or boys is called • Pubic hair grows (three-to-six months after breasts “Precocious Puberty.” develop). • Other body hair grows. -

Precocious Puberty: a Red Flag for Malignancy in Childhood

CLINICAL Paul R. D’Alessandro, MD, MSc, Jillian Hamilton, MBChB, Karine Khatchadourian, MD, MSc, Ewa Lunaczek-Motyka, MD, Kirk R. Schultz, MD, Daniel Metzger, MD, Rebecca J. Deyell, MD, MHSc Precocious puberty: A red flag for malignancy in childhood Three clinical cases of precocious puberty resulting from rare but serious functional solid tumors in children highlight the need for physicians to identify the condition early and refer to tertiary care to minimize morbidity and optimize survival. ABSTRACT: Pediatric solid tumors have a range of 1-3 Dr D’Alessandro is a pediatric hematology/ abnormalities. These tumors may present clinical presentations, including those driven by oncology subspecialty resident in the with early onset of isosexual or contrasexual the ectopic production of hormones secreted by Division of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, puberty as a first symptom. Treatment may some malignancies. Functional tumors lead to a and Bone Marrow Transplant, Department involve surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radio- variety of presentations, including Cushing syn- of Pediatrics, University of British therapy. Genetic testing or counseling may be drome, growth acceleration, abnormal virilization Columbia, British Columbia Children’s indicated for families. Early identification mini- or feminization, and hypertension with electrolyte Hospital Research Institute. mizes disease-related morbidity and mortality abnormalities. Precocious puberty, the onset of Dr Hamilton is a general practice specialty and optimizes outcomes. We present illustrative secondary sexual characteristics before age 8 in trainee, NHS Forth Valley, Larbert, cases of functional solid tumors in children from girls or 9 in boys, may be a warning sign of occult United Kingdom. Dr Khatchadourian is a British Columbia with the aim of educating malignancy. -

Hypogonadism in Adolescence 173:1 R15–R24 Review

A A Dwyer and others Hypogonadism in adolescence 173:1 R15–R24 Review TRANSITION IN ENDOCRINOLOGY Hypogonadism in adolescence Andrew A Dwyer1,2, Franziska Phan-Hug1,3, Michael Hauschild1,3, Eglantine Elowe-Gruau1,3 and Nelly Pitteloud1,2,3,4 1Center for Endocrinology and Metabolism in Young Adults (CEMjA), 2Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Correspondence Service and 3Division of Pediatric Endocrinology Diabetology and Obesity, Department of Pediatric Medicine and should be addressed Surgery, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), Rue du Bugnon 46, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland and to N Pitteloud 4Department of Physiology, Faculty of Biology and Medicine, University of Lausanne, Rue du Bugnon 7, Email 1005 Lausanne, Switzerland [email protected] Abstract Puberty is a remarkable developmental process with the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis culminating in reproductive capacity. It is accompanied by cognitive, psychological, emotional, and sociocultural changes. There is wide variation in the timing of pubertal onset, and this process is affected by genetic and environmental influences. Disrupted puberty (delayed or absent) leading to hypogonadism may be caused by congenital or acquired etiologies and can have significant impact on both physical and psychosocial well-being. While adolescence is a time of growing autonomy and independence, it is also a time of vulnerability and thus, the impact of hypogonadism can have lasting effects. This review highlights the various forms of hypogonadism in adolescence and the clinical challenges in differentiating normal variants of puberty from pathological states. In addition, hormonal treatment, concerns regarding fertility, emotional support, and effective transition to adult care are discussed. European Journal of Endocrinology (2015) 173, R15–R24 European Journal of Endocrinology Introduction Adolescence is generally defined as the transitional phase (FSH)) (1, 2). -

Precocious Puberty

Precocious Puberty The Pituitary Gland: The "Master Gland" The pituitary gland, which is often referred to as the "master gland", regulates the release of most of the body's hormones (chemical messengers that send information to different parts of the body). It is a pea-sized gland that is located underneath the brain. The pituitary gland controls the release of thyroid, adrenal, growth and sex hormones. The hypothalamus, located in the brain above the pituitary gland, regulates the release of hormones from the pituitary gland. Hormones: The "Chemical Messengers" Chemical messengers that carry information from one cell to another in the body. Hormones are carried throughout body by the blood, and are responsible for regulating many body functions. The body makes many hormones (e.g., thyroid, growth, sex and adrenal hormones) that work together to maintain normal bodily function. Hormones involved in the control of puberty include: GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone, which comes from the brain in boys and in girls. Other androgens from the adrenal glands (located near the kidneys) produce pubic and axillary hair at the time of puberty. Estrogen: A female sex hormone, which is responsible for breast development in girls. It is made mainly by the ovaries, but is also present in boys in smaller amounts. Sex Hormones: Responsible for the development of pubertal signs as well as changes in behavior and the ability to have children. Precocious Puberty Precocious puberty means having signs of puberty (e.g., pubic hair or breast development) at an earlier age than usual. Normal Puberty There is a wide range of ages at which individuals normally start puberty. -

MECHANISMS in ENDOCRINOLOGY: Novel Genetic Causes of Short Stature

J M Wit and others Genetics of short stature 174:4 R145–R173 Review MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY Novel genetic causes of short stature 1 1 2 2 Jan M Wit , Wilma Oostdijk , Monique Losekoot , Hermine A van Duyvenvoorde , Correspondence Claudia A L Ruivenkamp2 and Sarina G Kant2 should be addressed to J M Wit Departments of 1Paediatrics and 2Clinical Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, Email The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract The fast technological development, particularly single nucleotide polymorphism array, array-comparative genomic hybridization, and whole exome sequencing, has led to the discovery of many novel genetic causes of growth failure. In this review we discuss a selection of these, according to a diagnostic classification centred on the epiphyseal growth plate. We successively discuss disorders in hormone signalling, paracrine factors, matrix molecules, intracellular pathways, and fundamental cellular processes, followed by chromosomal aberrations including copy number variants (CNVs) and imprinting disorders associated with short stature. Many novel causes of GH deficiency (GHD) as part of combined pituitary hormone deficiency have been uncovered. The most frequent genetic causes of isolated GHD are GH1 and GHRHR defects, but several novel causes have recently been found, such as GHSR, RNPC3, and IFT172 mutations. Besides well-defined causes of GH insensitivity (GHR, STAT5B, IGFALS, IGF1 defects), disorders of NFkB signalling, STAT3 and IGF2 have recently been discovered. Heterozygous IGF1R defects are a relatively frequent cause of prenatal and postnatal growth retardation. TRHA mutations cause a syndromic form of short stature with elevated T3/T4 ratio. Disorders of signalling of various paracrine factors (FGFs, BMPs, WNTs, PTHrP/IHH, and CNP/NPR2) or genetic defects affecting cartilage extracellular matrix usually cause disproportionate short stature. -

ANDROGEN INSENSITIVITY SYNDROME AMONG COUSIN SISTERS - a RARE ENTITY Sarah Ramamurthy *1, Aravindhan Karuppusamy 2

International Journal of Anatomy and Research, Int J Anat Res 2018, Vol 6(3.2):5564-67. ISSN 2321-4287 Case Study DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2018.282 ANDROGEN INSENSITIVITY SYNDROME AMONG COUSIN SISTERS - A RARE ENTITY Sarah Ramamurthy *1, Aravindhan Karuppusamy 2. *1 Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalapet, Pondicherry, India. 2 Additional Professor and Head, Department of Anatomy, JIPMER, Pondicherry, India. ABSTRACT Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS), is a X-linked disorder characterized by resistance to androgen caused by mutation of androgen receptor gene in which XY karyotype individuals exhibit female phenotype. AIS is characterised by evidence of feminization (under masculinization) of the external genitalia at birth, abnormal secondary sexual development at puberty, and infertility in individuals with 46 XY karyotype. We are presenting here a familial case of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome in south Indian Population. 46 XY karyotype was found in two subjects who were cousin sisters with female phenotype,who presented with primary amenorrhoea. Comet assay was done, which showed results comparable with normal males. In both girls’ inguinal gonads was present which was removed and hormonal therapy with estrogen was given to prevent osteoporosis. Androgen insensitivity syndrome can be inherited as an X linked disorder as evidenced by previous studies. KEY WORDS: testicular feminization syndrome, Androgen Receptor Deficiency, Primary amennorrhea, Comet