Buffalo Soldiers: the Formation of the Tenth Cavalry Regiment from September 1866 to August 1867 C"}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid Into Alabama'

H-Indiana McMullen on Willett, 'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama' Review published on Monday, May 1, 2000 Robert L. Willett, Jr. The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama. Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 1999. 232 pp. $18.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-57860-025-0. Reviewed by Glenn L. McMullen (Curator of Manuscripts and Archives, Indiana Historical Society) Published on H-Indiana (May, 2000) A Union Cavalry Raid Steeped in Misfortune Robert L. Willett's The Lightning Mule Brigade is the first book-length treatment of Indiana Colonel Abel D. Streight's Independent Provisional Brigade and its three-week raid in spring 1863 through Northern Alabama to Rome, Georgia. The raid, the goal of which was to cut Confederate railroad lines between Atlanta and Chattanooga, was, in Willett's words, a "tragi-comic war episode" (8). The comic aspects stemmed from the fact that the raiding force was largely infantry, mounted not on horses but on fractious mules, anything but lightning-like, justified by military authorities as necessary to take it through the Alabama mountains. Willett's well-written and often moving narrative shifts between the forces of the two Union commanders (Streight and Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge) and two Confederate commanders (Col. Phillip Roddey and Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest) who were central to the story, staying in one camp for a while, then moving to another. The result is a highly textured and complex, but enjoyable, narrative. Abel Streight, who had no formal military training, was proprietor of the Railroad City Publishing Company and the New Lumber Yard in Indianapolis when the war began. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

2011-Summer Timelines

OMENA TIMELINES Remembering Omena’s Generals and … The American Civil War Sesquicentennial A PUBLICATION OF THE OMENA HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 2011 From the Editor Jim Miller s you can see, our Timelines publica- tion has changed quite a bit. We have A taken it from an institutional “newslet- ter” to a full-blown magazine. To make this all possible, we needed to publish it annually rather than bi-annually. By doing so, we will be able to provide more information with an historical focus rather than the “news” focus. Bulletins and OHS news will be sent in multiple ways; by e-mail, through our website, published in the Leelanau Enterprise or through special mailings. We hope you like our new look! is the offi cial publication Because 2011 is the sesquicentennial year for Timelines of the Omena Historical Society (OHS), the start of the Civil War, it was only fi tting authorized by its Board of Directors and that we provide appropriately related matter published annually. for this issue. We are focusing on Omena’s three Civil War generals and other points that should Mailing address: pique your interest. P.O. Box 75 I want to take this opportunity to thank Omena, Michigan 49674 Suzie Mulligan for her hard work as the long- www.omenahistoricalsociety.com standing layout person for Timelines. Her sage Timelines advice saved me on several occasions and her Editor: Jim Miller expertise in laying out Timelines has been Historical Advisor: Joey Bensley invaluable to us. Th anks Suzie, I truly appre- Editorial Staff : Joan Blount, Kathy Miller, ciate all your help. -

The Buffalo Soldiers Study, March 2019

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUFFALO SOLDIERS STUDY MARCH 2019 BUFFALO SOLDIERS STUDY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION The study explores the Buffalo Soldiers’ stewardship role in the early years of the national Legislation and Purpose park system and identifies NPS sites associated with the history of the Buffalo Soldiers and their The National Defense Authorization Act of 2015, post-Civil War military service. In this study, Public Law 113-291, authorized the Secretary of the term “stewardship” is defined as the total the Interior to conduct a study to examine: management of the parks that the US Army carried out, including the Buffalo Soldiers. “The role of the Buffalo Soldiers in the early Stewardship tasks comprised constructing and years of the national park system, including developing park features such as access roads an evaluation of appropriate ways to enhance and trails; performing regular maintenance historical research, education, interpretation, functions; undertaking law enforcement within and public awareness of the Buffalo Soldiers in park boundaries; and completing associated the national parks, including ways to link the administrative tasks, among other duties. To a story to the development of national parks and lesser extent, the study also identifies sites not African American military service following the managed by the National Park Service but still Civil War.” associated with the service of the Buffalo Soldiers. The geographic scope of the study is nationwide. To meet this purpose, the goals of this study are to • evaluate ways to increase public awareness Study Process and understanding of Buffalo Soldiers in the early history of the National Park Service; and The process of developing this study involved five phases, with each phase building on and refining • evaluate ways to enhance historical research, suggestions developed during the previous phase. -

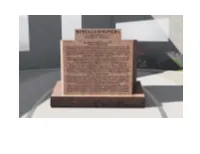

The Tucson Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Project

The Tucson Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Project The Tucson Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Project A COLLABORATION BETWEEN: CITY OF TUCSON, WARD 5 ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE GREATER SOUTHERN ARIZONA AREA CHAPTER, 9TH and 10TH CAVALRY ASSOCIATION 9TH MEMORIAL UNITED STATES CAVALRY, INC 10TH CAVALRY TROOP B FOUNDATION OMEGA PSI PHI FRATENITY We Can, We Will, We Are So Others Can Learn The Tucson Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Subject Page Memorial Project Overview 1 The Need 1 The Purpose 1 Goals 1 Mission Statement 1 Their Story - Our History 2 Buffalo Soldier Background 2 The Buffalo Soldier Legacy 2 Black American Officers 2 Buffalo Soldier Medal of Honor Recipients 3 Memorial Project Coalition Members 6 Current Coalition Members 6 Other Partnership Possibilities 6 Letters of Support 7 Memorial Project Design 7 Memorial Design 7 Other Memorial Features 7 Possible Feature Examples 8 Proposed Memorial Layout 9 Fundraising 10 Fundraising Ideas 10 Other Funding Sources 10 Project Financial Information 10 Budget (Overall) 10 Budget - Phase I (Planning and Memorial Preparation) 11 Budget - Phase II (Project Features) 11 Budget - Phase III (Project Construction) 11 The Tucson Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Project TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUED Timeline/Milestones 11 Location Site and its Benefits 12 The Quincie Douglas Neighborhood Center 12 Quincie Douglas Bio 12 Location Benefits 13 Audience 13 Memorial Awareness Trend 13 Audience 13 Appendix A 14 Proposed Resolution The Tucson Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Project MEMORIAL PROJECT OVERVIEW Over the past seven years, various Buffalo Soldier organizations have been working with Tucson City Council Members to honor the contributions of some of America’s greatest heroes, the Buffalo Soldiers. -

Publication Number: M-1821 Publication Title: Compiled Military

Publication Number: M-1821 Publication Title: Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 8th through 13th, including the 11th (new) Date Published: 2000 COMPILED MILITARY SERVICE RECORDS OF VOLUNTEER UNION SOLDIERS WHO SERVED WITH THE UNITED STATES COLORED TROOPS: INFANTRY ORGANIZATIONS, 8TH THROUGH 13TH, INCLUDING THE 11TH (NEW) Introduction On the 109 rolls of this microfilm publication, M1821, are reproduced the compiled military service records of volunteer Union soldiers belongs to the 8th through the 13th infantry units, including the 11th (new) organized for service with the United States Colored Troops (USCT). The USCT included 7 numbered cavalry regiments; 13 numbered artillery regiments plus 1 independent battery; 144 numbered infantry regiments; Brigade Bands Nos. 1 & 2 (Corps d'Afrique and U.S. Colored Troops); Powell's Regiment Colored Infantry; Southard's Company Colored Infantry; Quartermaster Detachment; Pioneer Corps, 1st Division, 16th Army Corps; Pioneer Corps, Cavalry Division, 16th Army Corps; Unassigned Company A Colored Infantry; and Unassigned USCT. There are also miscellaneous service cards arranged alphabetically by surname at the end of the unit records. The records reproduced are part of the Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's-1917, Record Group (RG) 94. Background Since the time of the American Revolution, African Americans have volunteered to serve their country in time of war. The Civil War was no exception. Official sanction was the difficulty. In the fall of 1862 there were four Union regiments of African Americans raised in New Orleans, LA: the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard, and the 1st Louisiana Heavy Artillery (African Descent). -

African American Soldiers in the Philippine War: An

AFRIC AN AMERICAN SOLDIERS IN THE PHILIPPINE WAR: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF BUFFALO SOLDIERS DURING THE SPANISH AMERICAN WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH, 1898-1902 Christopher M. Redgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Geoffrey D. W. Wawro, Major Professor Richard Lowe, Committee Member G. L. Seligmann, Jr., Committee Member Richard G. Vedder, Committee Member Jennifer Jensen Wallach, Committee Member Harold Tanner, Chair of the Department of History David Holdeman, Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Redgraves, Christopher M. African American Soldiers in the Philippine War: An Examination of the Contributions of Buffalo Soldiers during the Spanish American War and Its Aftermath, 1898–1902. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August 2017, 294 pp., 8 tables, bibliography, 120 titles. During the Philippine War, 1899 – 1902, America attempted to quell an uprising from the Filipino people. Four regular army regiments of black soldiers, the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry served in this conflict. Alongside the regular army regiments, two volunteer regiments of black soldiers, the Forty-Eighth and Forty-Ninth, also served. During and after the war these regiments received little attention from the press, public, or even historians. These black regiments served in a variety of duties in the Philippines, primarily these regiments served on the islands of Luzon and Samar. The main role of these regiments focused on garrisoning sections of the Philippines and helping to end the insurrection. To carry out this mission, the regiments undertook a variety of duties including scouting, fighting insurgents and ladrones (bandits), creating local civil governments, and improving infrastructure. -

608Ca27da37e1.Pdf.Pdf

BLACK SOLDIERS IN THE WEST: A PROUD TRADITION During the Civil War over 180,000 Black Americans served in the Union Army and Navy. More than 33,000 died. After the war, the future of black men in the nation’s military was in doubt. In 1866, however, Congress authorized black Americans to serve in the peacetime army of the United States in segregated units mostly commanded by white officers. Two cavalry and four infantry regiments were created and designated the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments and the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Infantry Regiments. In 1869, Congress enacted a troop reduction and consolidation leading to the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Infantry Regiments being re- designated as the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments. The four remaining regiments, the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments and the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments would become known as the “Buffalo Soldiers.” During the 19th century, Buffalo Soldiers served in Arizona, California, Colorado, the Dakotas, Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming. In Arizona they garrisoned such posts s as Fort Apache, Fort Bowie, Fort Grant, Fort Huachuca, Fort Verde, and Fort Whipple. Fort Huachuca enjoys the distinction of being the only military installation having served as home to each of the four Buffalo Soldier regiments at one time or another. Buffalo Soldiers played a major role in the settlement and development of the American West. They performed such duties as guarding and delivering the mail as well as escorting and or guarding stagecoaches, railroad crews, and surveyors. They built roads and telegraph lines, mapped and explored the territories and provided security for westward expansion. -

Tuesday, February 18, 2020

Camera #1 Good Morning Cougars! Today is Tuesday, February 18th and my name is ______ . Camera #1 And my name is _______ Welcome to the Cabin John Morning News Show!! Camera #1 Please stand for the pledge of allegiance. (Pause for a 5 seconds) Camera #1 I pledge allegiance to the flag of the united states of America, and to the republic for which it stands, one nation, under god, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Camera #1 Please be seated. (Pause for a 3 seconds) Here’s _____ and _____with today’s weather and more announcements for the day. Camera #2 Thank you _____. Todays weather will be cloudy with occasional showers and sunset at 5:48pm today. Camera #2 We will have a high near 60 degrees and winds from the south of about 10 to 15 miles per hour. Camera #2 Attention CJMS, International Night planning is underway! We invite all students, their families and staff for the CJMS International Night! Camera #2 On Friday, March 6th, Cabin John will go International with a celebration of our cultures! Camera #2 Please help make this a night to remember by attending this event. Better yet, you can volunteer with a performance, or host a table, representing the best of your favorite country! Camera #2 Sign up links are available on the Cabin John website. Sign up to host a Country table, or to Perform, or sign up for both experiences! Camera #2 We encourage families to work together, too!! We hope you will support and attend this event! Camera #2 The deadline for any and all SSL forms is Friday June 5th, 2020. -

The Role of Officer Selection and Training on the Successful Formation and Employment of U.S

THE ROLE OF OFFICER SELECTION AND TRAINING ON THE SUCCESSFUL FORMATION AND EMPLOYMENT OF U.S. COLORED TROOPS IN THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1863-1865 A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE Military History by DANIEL V. VAN EVERY, MAJOR, US ARMY B.S., Minnesota State University, Mankato, Minnesota, 1999 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2011-01 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 10-06-2011 Master‘s Thesis AUG 2010 – JUN 2011 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER The Role of Officer Selection and Training on the Successful 5b. -

In 1848 the Slave-Turned-Abolitionist Frederick Douglass Wrote In

The Union LeagUe, BLack Leaders, and The recrUiTmenT of PhiLadeLPhia’s african american civiL War regimenTs Andrew T. Tremel n 1848 the slave-turned-abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote in Ithe National Anti-Slavery Standard newspaper that Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, “more than any other [city] in our land, holds the destiny of our people.”1 Yet Douglass was also one of the biggest critics of the city’s treatment of its black citizens. He penned a censure in 1862: “There is not perhaps anywhere to be found a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than Philadelphia.”2 There were a number of other critics. On March 4, 1863, the Christian Recorder, the official organ of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, commented after race riots in Detroit, “Even here, in the city of Philadelphia, in many places it is almost impossible for a respectable colored per- son to walk the streets without being assaulted.”3 To be sure, Philadelphia’s early residents showed some mod- erate sympathy with black citizens, especially through the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, but as the nineteenth century progressed, Philadelphia witnessed increased racial tension and a number of riots. In 1848 Douglass wrote in response to these pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013. Copyright © 2013 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 09 Jan 2019 20:56:18 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pennsylvania history attitudes, “The Philadelphians were apathetic and neglectful of their duty to the black community as a whole.” The 1850s became a period of adjustment for the antislavery movement.