Criminal Justice Proposed Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined Seventeenth to Twenty-Second Periodic Reports Submitted by Botswana Under Article 9 of the Convention, Due Since 2009*

United Nations CERD/C/BWA/17-22 International Convention on Distr.: General 21 July 2020 the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination Original: English English, French and Spanish only Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Combined seventeenth to twenty-second periodic reports submitted by Botswana under article 9 of the Convention, due since 2009* [Date received: 30 January 2020] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.20-09810(E) CERD/C/BWA/17-22 General Information Replies to the list of issues prior to reporting CERD/C/BWA/QPR/17-22 Reply to paragraph 1 of the list of issues 1. In Botswana, the primary legislation that offers protection to human rights covered by the Convention is the Constitution. Section 3 of the Constitution accords fundamental rights and freedoms to every person on a non-discriminatory basis, including race. In addition, Section 15 of the Constitution specifically prohibits discrimination on the basis of, among others, race. 2. Since Botswana’s last report, significant legislative developments which promote and protect human rights covered by this Convention have taken place. These include the enactment of the Local Government Act of 2008, Cybercrime and Computer Related Crimes Act of 2018 and the Children’s Act of 2009. These laws incorporate the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of race in public procurement, transmission of electronic material and administration of the Children’s Act, respectively. 3. In terms of institutional framework, the Government has established a Human Rights Unit within the Ministry of Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration. -

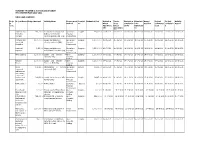

MINISTRY of DEFENCE JUSTICE and SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Ct Code Project Name Budget Amount Ac

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE JUSTICE AND SECURITY PROCUREMEN PLAN 2021-2022 MDJS HEADQUARTERS Proje Project Name Budget Amount Activity Name Procurement Descipli Estimated Cost Invitation Tender Evaluation Submissio Award Project Project Activity ct Method ne Direct Close completion n for Decision Commence Completio Report Code Appointme Direct by PE Adjudicati ment n ntte Appointme on ntte Uniforms and 143,230.00 A Contract for Supply and Quotations Supplies 143,230.00 20-04-2021 08-05-2021 08-04-2021 04-12-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 Protective Delivery of Protective Proposal Clothing Clothing and Uniform (HQ) Procurement Domestic and 1,500,000.00 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 1,500,000.00 16-08-2021 31-08-2021 31-08-2021 09-06-2021 15-06-2021 15-06-2021 22-06-2021 26-08-2021 household cleaning materials (HQ) Proposal Requisites Procurement Incidental 2,350,000 Supply and delivery of Quotations Supplies 2,350,000.00 16-07-2021 08-03-2021 08-05-2021 08-09-2021 08-12-2021 16-08-2021 20-08-2021 23-08-2021 Expenses Refreshments for MDJS (HQ) Proposal Procurement Office supplies 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Sationery (HQ) Domestic Bidding Genuine 1,500,000.00 Supply and Delivery of Open Supplies 1,500,000.00 14-06-2021 07-09-2021 14-07-2021 23-07-2021 29-07-2021 08-02-2021 23-08-2021 27-08-2021 Toners Toners to MDJS HQ Domestic Bidding Office 172,110.00 Maintanance of running Quotations Service -

Tender Advert

TENDER ADVERT www.etender.co.bw Botswana Prison Service - DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 Companies are invited to express their interest in the consultancy services on conditions of service for non-uniformed (civilian) staff of the Botswana Prison Service Closing: 21 January 2021 09H00 Site Visit: Contacts Senior Superintendent Ntshebe 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Senior Superintendent Bedi 3611711/21 3975398/003 [email protected] Collection : The physical address for the collection of Tender Document is Botswana Prison Service Headquarters, Broadhurst Industrial, Plot No. 10211, next to Mafulo House at the Supplies Office. Documents may be collected during office days between 07:30 and 12:45 and from 13:45 to 16:30 with effect from 14th December 2020. Queries relating to the issuance of these documents may be addressed to: Senior Superintendent Ntshebe and Senior Superintendent Bedi at Telephone No. 3611711/21, Fax Nos. 3975398/003, Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Fee: Delivery: The names and addresses of companies should be clearly marked on the envelope. One (1) original marked “Original” plus two (2) copies marked “Copy” must be hand-delivered in sealed envelopes. Identification details to be shown on each tender offer are: “Tender No. DJS/MTC/PRI 031/2020/2021 - Expression of Interest for Consultancy Services on Conditions of Service for Non-Uniformed (Civilian) Staff of the Botswana Prison Service”. Tender offers will be submitted to The Secretary, Ministerial Tender Committee, Ministry of Defence, Justice and Security Headquarters, Central Square Building, Ground Floor, Office No. 004 at the Tender Opening Hall, Gaborone, Central Business District, Phase 2, Plot No. -

Republic of Botswana - European Community

Republic of Botswana - European Community JOINT ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Country Performance ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Update on the political situation and political governance ................................................................. 4 1.2 Update on the economic situation and economic governance............................................................. 6 1.3 Update on the poverty and social situation......................................................................................... 10 1.4 Update on the environmental situation............................................................................................... 12 2. Overview of past and ongoing co-operation................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Reporting on the financial performance of EDF resources............................................................... 13 2.2 Reporting on General and Sector Budget Support............................................................................ 14 2.3 Project and programmes in the focal and non-focal areas................................................................ 15 2.3.1 Focal Sector: Human Resource Development......................................................................... -

Botswana Country Report-Annex-4 4Th Interim Techical Report

PROMOTING PARTNERSHIPS FOR CRIMEPREVENTION BETWEEN THE STATE AND PRIVATE SECURITY PROVIDERS IN BOTSWANA BY MPHO MOLOMO AND ZIBANI MAUNDENI Introduction Botswana stands out as the only African country to have sustained an unbroken record of liberal democracy and political stability since independence. The country has been dubbed the ‘African Miracle’ (Thumberg Hartland, 1978; Samatar, 1999). It is widely regarded as a success story arising from its exploitation and utilisation of natural resources, establishing a strong state, institutional and administrative capacity, prudent macro-economic stability and strong political leadership. These attributes, together with the careful blending of traditional and modern institutions have afforded Botswana a rare opportunity of political stability in the Africa region characterised by political and social strife. The expectation is that the economic growth will bring about development and security. However, a critical analysis of Botswana’s development trajectory indicates that the country’s prosperity has it attendant problems of poverty, unemployment, inequalities and crime. Historically crime prevention was a preserve of the state using state security agencies as the police, military, prisons and other state apparatus, such as, the courts and laws. However, since the late 1980s with the expanded definition of security from the narrow static conception to include human security, it has become apparent that state agencies alone cannot combat the rising levels of crime. The police in recognising that alone they cannot cope with the crime levels have been innovative and embarked on other models of public policing, such as, community policing as a public society partnership to combat crime. To further cater for the huge demand on policing, other actors, which are non-state actors; in particular private security firms have come in, especially in the urban market and occupy a special niche to provide a service to those who can afford to pay for it. -

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

State of the Nation Address to the 3Rd Session of the 10Th Parliament

State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament 08/11/11 State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament State of the Nation Address to the 3rd Session of the 10th Parliament STATE OF THE NATION ADDRESS BY HIS EXCELLENCY Lt. GEN. SERETSE KHAMA IAN KHAMA PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE TENTH PARLIAMENT "BOTSWANA FIRST" 7th November 2011, GABORONE: 1. Madam Speaker, before we begin, I request that we all observe a moment of silence for those who have departed during the past year. Thank you. 2. Let me also take this opportunity to commend the Leader of the House, His Honour the Vice President, on his recent well deserved awards. In addition to the Naledi ya Botswana, which he received for his illustrious service to the nation, His Honour also did us proud when he received a World Citizen Award for his international, as well as domestic, contributions. I am sure other members will agree with me that these awards are deserving recognition of a true statesman. 3. Madam Speaker, it is a renewed privilege to address this Honourable House and the nation. This annual occasion allows us to step back and take a broader look at the critical challenges we face, along with the opportunities we can all embrace when we put the interests of our country first. 4. As I once more appear before you, I am mindful of the fact that this address will be the subject of further deliberations. -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

Government Gazette

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Vol. XV, No. 64 GABORONE 21st October, 1977. CONTENTS Page Presidential Awards — G.N. No. 598of 1977 ......................................................................................... 854 Acting Appointment - Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Mineral Resources and Water Affairs G.N. No. 599 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 854 Acting Appointment - Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance and Development Planning — G.N. No. No. 600 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 855 Acting Appointment - Auditor-General — G.N. No. 601 of 1977......................................................... 855 Appointment of General Registration Period — G.N. No. 602 of 1977 ................................................ 855 Application for Change in Establishment of School — G.N. No. 603 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 856 G.N. No. 604 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 856 G.N. No. 605 of 1977 ......................................................................................................................... 856 G.N. No. 606 of 1977 ........................................................................................................................ -

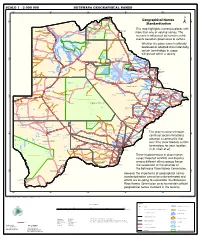

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

New List of Archaeologists 2019.Pdf

P Department of National Museum Monument and Art Gallery 331 Independence Avenue Gaborone, Botswana Private Bag 00114 Tel: (267) 3974616 (267) 3610400 Fax: (267) 3902797 Email: [email protected] Website: www.national- museum.gov.bw A LIST OF APPROVED ARCHAEOLOGISTS 2019 Our reference Dr Alfred Tsheboeng Dr Alinah Segobye P.O. Box 2789 University of Botswana Gaborone International Finance Park P/Bag 0022, Gaborone Plot 128,Kgale Court, Unit 8, Gaborone Tel: 3162036 Cel: 71374291 Tel: 3552281 Cel: 71625018 e-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Catrien Van Waarden Dr Nick Walker Marope Research Achilles Investments Pty Ltd P.O. Box 910, Francistown Gaborone Tel: 2414257 Cell: 71378415 Email: [email protected] [email protected] P. Sekgarametso-Modikwa Pena Monageng Archaeological Resources Management Services Ditso Archaeological Surveys P.O. Box 601271 P/Bag 0029, suit no 285 Gaborone Postnet Mogoditshane Tel: 3922289 cell: 71653378 Tel: 3552267 Cell: 71728860 Fax: 3922289 Fax: 3938757 Email: [email protected] Mr. O.J. NOKO Mr. Donald Mookodi Crystal Touch (Pty) Ltd Geoarch Investment Pty Ltd Postnet Kgale View P.O. Box 10111 P/Bag 351 suite 418 Gaborone Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (5442552 Cell: 71710397 Cell: 72202884 Fax: 3975566 Email: [email protected]/ 1 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Mr. Oscar Motsumi Nyatsego L. Baeletsi Watershed (Pty) Ltd Kgato-Go-Ya-Pele (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 3347 P.O. Box 202850 Gaborone, Botswana Gaborone Tel: (09267) 316400/3699840 Tel/Fax: 3185133 Cel: 71676356 Cel: (09267) 71313089/74222285 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] motsumio@botsnet-bw Dr Susan O. -

CIMS Newsletter, Vol 5, Issue 2, 2013

Volume 5 • Issue 2 MAY 2013 Administration of Justice Newsletter E- GOVERNANCE TEAM TAKES WEBSITE TO STAFF ..................5 Gauging Of Stations ........6 INSIDE THIS ISSUE MR G. NTHOMIWA APPOINTED A JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT ......3 DEFENCE ATTACHES VISIT THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE .........9 HIGH COURT JUDGES VISIT TANZANIAN JUDICIAL SERVICE COMMISSION DTCB .........4 DELEGATION VISITS BOTSWANA...................... 12 MOCHUDI MAGISTRATE COURT- A SUCCESS DURING THE GAUGING OF MARCH- SEPTEMBER 2012......18 19 Ask the Guru!.... MR G. NTHOMIWA Editorial APPOINTED A JUDGE Vision he CIMS team would like to commend the good work that the users all over the courts continue “Access to Justice to give in. Users your never ending, T for All by 2016.” relentless commitment towards CRMS is beginning to bear fruits as evidenced by the October 2012-March 2013 gauging results. When the lowest court in rating used to garner as little as 35% , this time the last court has garnered a comfortable 53%. And the highest court this time has also broken record. At 89%, this is the highest ever for the number one station in the history of gauging. This is remarkable!!! However we have not completely won the battle, our criminal cases and scanning are still the areas that need our special Mission attention. What needs to be done? Please see the full article by Ms G Dintsi. To uphold human rights, Democracy and the rule of Ms King covers the Legal Year opening celebration. Please enjoy the article and law in accordance with the the splash of pictures that accompany the Constitution of Botswana article.