Philippinean Vegetation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dipterocarpaceae)

DNA Sequence-Based Identification and Molecular Phylogeny Within Subfamily Dipterocarpoideae (Dipterocarpaceae) Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) at Forest Genetics and Forest Tree Breeding, Büsgen Institute Faculty of Forest Sciences and Forest Ecology Georg-August-Universität Göttingen By Essy Harnelly (Born in Banda Aceh, Indonesia) Göttingen, 2013 Supervisor : Prof. Dr. Reiner Finkeldey Referee : Prof. Dr. Reiner Finkeldey Co-referee : Prof. Dr. Holger Kreft Date of Disputation : 09.01.2013 2 To My Family 3 Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Dr. Reiner Finkeldey for accepting me as his PhD student, for his support, helpful advice and guidance throughout my study. I am very grateful that he gave me this valuable chance to join his highly motivated international working group. I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Holger Kreft and Prof. Dr. Raphl Mitlöhner, who agreed to be my co-referee and member of examination team. I am grateful to Dr. Kathleen Prinz for her guidance, advice and support throughout my research as well as during the writing process. My deepest thankfulness goes to Dr. Sarah Seifert (in memoriam) for valuable discussion of my topic, summary translation and proof reading. I would also acknowledge Dr. Barbara Vornam for her guidance and numerous valuable discussions about my research topic. I would present my deep appreciation to Dr. Amarylis Vidalis, for her brilliant ideas to improve my understanding of my project. My sincere thanks are to Prof. Dr. Elizabeth Gillet for various enlightening discussions not only about the statistical matter, but also my health issues. -

Development of Instant Sinigang Powder from Katmon Fruit (Dellenia Philippinensis)

E-ISSN: 2476-9606 Abstract Proceedings International Scholars Conference Volume 7 Issue 1, October 2019, pp.367-383 https://doi.org/10.35974/isc.v7i1.1034 Development of Instant Sinigang Powder from Katmon Fruit (Dellenia Philippinensis) Marchelita Beverly Tappy1, Sophiya Celine Dellosa2, Teejay Malabonga3 1,2,3Adventist University of the Philippines [email protected] ABSTRACT Katmon Fruit (Dillenia Philippinensis) is a fruit tree commonly use in the rural area in the Philippines. Katmon is eaten as fruit but is not very popular because of the unacceptable taste that resembles a green sour apple. The purpose of this study is to develop an instant sinigang powder as a base ingredient of sinigang and using the natural sour taste for sinigang dish. This study use katmon fruit, shiitake mushroom, garlic, iodized salt, and sugar to develop an instant sinigang mix powder. It were dehydrated using the Multi-Commodity Heat Pump Dryer for 13 hours. These were powdered using a grinder mixed with iodized salt and sugar. The nutrient content was computed using iFNRI online software. Thirty participants comprising: 10 faculty, 10 dormitory students,10 senior high school students did the taste test. The results revealed that the product was liked very much in terms of color, texture, taste, aroma, and appearance. The instant sinigang powder is stored in a polyethylene metalized zip lock packaging 8.5 x 14cm. The cost per serving is PhP 37.5 It is cheaper and has more nutritional value compared to other products. The study recommending for more enhancement in terms of flavour of instant sinigang powder from katmon additional ingredient from natural sources to have more tasty and more nutritional content. -

Tropical Plant-Animal Interactions: Linking Defaunation with Seed Predation, and Resource- Dependent Co-Occurrence

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2021 TROPICAL PLANT-ANIMAL INTERACTIONS: LINKING DEFAUNATION WITH SEED PREDATION, AND RESOURCE- DEPENDENT CO-OCCURRENCE Peter Jeffrey Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Williams, Peter Jeffrey, "TROPICAL PLANT-ANIMAL INTERACTIONS: LINKING DEFAUNATION WITH SEED PREDATION, AND RESOURCE-DEPENDENT CO-OCCURRENCE" (2021). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11777. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TROPICAL PLANT-ANIMAL INTERACTIONS: LINKING DEFAUNATION WITH SEED PREDATION, AND RESOURCE-DEPENDENT CO-OCCURRENCE By PETER JEFFREY WILLIAMS B.S., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, 2014 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology – Ecology and Evolution The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2021 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Graduate School Dean Jedediah F. Brodie, Chair Division of Biological Sciences Wildlife Biology Program John L. Maron Division of Biological Sciences Joshua J. Millspaugh Wildlife Biology Program Kim R. McConkey School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences University of Nottingham Malaysia Williams, Peter, Ph.D., Spring 2021 Biology Tropical plant-animal interactions: linking defaunation with seed predation, and resource- dependent co-occurrence Chairperson: Jedediah F. -

Renata Gabriela Vila Nova De Lima Filogenia E Distribuição

RENATA GABRIELA VILA NOVA DE LIMA FILOGENIA E DISTRIBUIÇÃO GEOGRÁFICA DE CHRYSOPHYLLUM L. COM ÊNFASE NA SEÇÃO VILLOCUSPIS A. DC. (SAPOTACEAE) RECIFE 2019 RENATA GABRIELA VILA NOVA DE LIMA FILOGENIA E DISTRIBUIÇÃO GEOGRÁFICA DE CHRYSOPHYLLUM L. COM ÊNFASE NA SEÇÃO VILLOCUSPIS A. DC. (SAPOTACEAE) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Botânica da Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE), como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Botânica. Orientadora: Carmen Silvia Zickel Coorientador: André Olmos Simões Coorientadora: Liliane Ferreira Lima RECIFE 2019 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Sistema Integrado de Bibliotecas da UFRPE Biblioteca Central, Recife-PE, Brasil L732f Lima, Renata Gabriela Vila Nova de Filogenia e distribuição geográfica de Chrysophyllum L. com ênfase na seção Villocuspis A. DC. (Sapotaceae) / Renata Gabriela Vila Nova de Lima. – 2019. 98 f. : il. Orientadora: Carmen Silvia Zickel. Coorientadores: André Olmos Simões e Liliane Ferreira Lima. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, Recife, BR-PE, 2019. Inclui referências e anexo(s). 1. Mata Atlântica 2. Filogenia 3. Plantas florestais 4. Sapotaceae I. Zickel, Carmen Silvia, orient. II. Simões, André Olmos, coorient. III. Lima, Liliane Ferreira, coorient. IV. Título CDD 581 ii RENATA GABRIELA VILA NOVA DE LIMA Filogenia e distribuição geográfica de Chrysophyllum L. com ênfase na seção Villocuspis A. DC. (Sapotaceae Juss.) Dissertação apresentada e -

Diversity and Composition of Plant Species in the Forest Over Limestone of Rajah Sikatuna Protected Landscape, Bohol, Philippines

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55790 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e55790 Research Article Diversity and composition of plant species in the forest over limestone of Rajah Sikatuna Protected Landscape, Bohol, Philippines Wilbert A. Aureo‡,§, Tomas D. Reyes|, Francis Carlo U. Mutia§, Reizl P. Jose ‡,§, Mary Beth Sarnowski¶ ‡ Department of Forestry and Environmental Sciences, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Bohol Island State University, Bohol, Philippines § Central Visayas Biodiversity Assessment and Conservation Program, Research and Development Office, Bohol Island State University, Bohol, Philippines | Institute of Renewable Natural Resources, College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines ¶ United States Peace Corps Philippines, Diosdado Macapagal Blvd, Pasay, 1300, Metro Manila, Philippines Corresponding author: Wilbert A. Aureo ([email protected]) Academic editor: Anatoliy Khapugin Received: 24 Jun 2020 | Accepted: 25 Sep 2020 | Published: 29 Dec 2020 Citation: Aureo WA, Reyes TD, Mutia FCU, Jose RP, Sarnowski MB (2020) Diversity and composition of plant species in the forest over limestone of Rajah Sikatuna Protected Landscape, Bohol, Philippines. Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e55790. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e55790 Abstract Rajah Sikatuna Protected Landscape (RSPL), considered the last frontier within the Central Visayas region, is an ideal location for flora and fauna research due to its rich biodiversity. This recent study was conducted to determine the plant species composition and diversity and to select priority areas for conservation to update management strategy. A field survey was carried out in fifteen (15) 20 m x 100 m nested plots established randomly in the forest over limestone of RSPL from July to October 2019. -

Nazrin Full Phd Thesis (150246576

Maintenance and conservation of Dipterocarp diversity in tropical forests _______________________________________________ Mohammad Nazrin B Abdul Malik A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Science Department of Animal and Plant Sciences November 2019 1 i Thesis abstract Many theories and hypotheses have been developed to explain the maintenance of diversity in plant communities, particularly in hyperdiverse tropical forests. Maintenance of the composition and diversity of tropical forests is vital, especially species of high commercial value. I focus on the high value dipterocarp timber species of Malaysia and Borneo as these have been extensive logged owing to increased demands from global timber trade. In this thesis, I explore the drivers of diversity of this group, as well as the determinants of global abundance, conservation and timber value. The most widely supported hypothesis for explaining tropical diversity is the Janzen Connell hypothesis. I experimentally tested the key elements of this, namely density and distance dependence, in two dipterocarp species. The results showed that different species exhibited different density and distance dependence effects. To further test the strength of this hypothesis, I conducted a meta-analysis combining multiple studies across tropical and temperate study sites, and with many species tested. It revealed significant support for the Janzen- Connell predictions in terms of distance and density dependence. Using a phylogenetic comparative approach, I highlight how environmental adaptation affects dipterocarp distribution, and the relationships of plant traits with ecological factors and conservation status. This analysis showed that environmental and ecological factors are related to plant traits and highlights the need for dipterocarp conservation priorities. -

Threatenedtaxa.Org Journal Ofthreatened 26 June 2020 (Online & Print) Vol

10.11609/jot.2020.12.9.15967-16194 www.threatenedtaxa.org Journal ofThreatened 26 June 2020 (Online & Print) Vol. 12 | No. 9 | Pages: 15967–16194 ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) JoTT PLATINUM OPEN ACCESS TaxaBuilding evidence for conservaton globally ISSN 0974-7907 (Online); ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Publisher Host Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society Zoo Outreach Organizaton www.wild.zooreach.org www.zooreach.org No. 12, Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampat - Kalapat Road, Saravanampat, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Ph: +91 9385339863 | www.threatenedtaxa.org Email: [email protected] EDITORS English Editors Mrs. Mira Bhojwani, Pune, India Founder & Chief Editor Dr. Fred Pluthero, Toronto, Canada Dr. Sanjay Molur Mr. P. Ilangovan, Chennai, India Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development (WILD) Society & Zoo Outreach Organizaton (ZOO), 12 Thiruvannamalai Nagar, Saravanampat, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, Web Design India Mrs. Latha G. Ravikumar, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, India Deputy Chief Editor Typesetng Dr. Neelesh Dahanukar Indian Insttute of Science Educaton and Research (IISER), Pune, Maharashtra, India Mr. Arul Jagadish, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Mrs. Radhika, ZOO, Coimbatore, India Managing Editor Mrs. Geetha, ZOO, Coimbatore India Mr. B. Ravichandran, WILD/ZOO, Coimbatore, India Mr. Ravindran, ZOO, Coimbatore India Associate Editors Fundraising/Communicatons Dr. B.A. Daniel, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Mrs. Payal B. Molur, Coimbatore, India Dr. Mandar Paingankar, Department of Zoology, Government Science College Gadchiroli, Chamorshi Road, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra 442605, India Dr. Ulrike Streicher, Wildlife Veterinarian, Eugene, Oregon, USA Editors/Reviewers Ms. Priyanka Iyer, ZOO/WILD, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641035, India Subject Editors 2016–2018 Fungi Editorial Board Ms. Sally Walker Dr. B. -

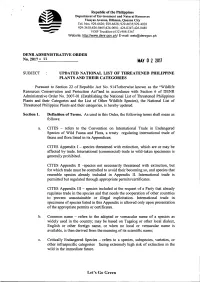

DENR Administrative Order. 2017. Updated National List of Threatened

Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Tel. Nos. 929-6626; 929-6628; 929-6635;929-4028 929-3618;426-0465;426-0001; 426-0347;426-0480 VOiP Trunkline (632) 988-3367 Website: http://www.denr.gov.ph/ E-mail: [email protected] DENR ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER No. 2017----------11 MAVO 2 2017 SUBJECT UPDATED NATIONAL LIST OF THREATENED PHILIPPINE PLANTS AND THEIR CATEGORIES Pursuant to Section 22 of Republic Act No. 9147otherwise known as the "Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act"and in accordance with Section 6 of DENR Administrative Order No. 2007-01 (Establishing the National List of Threatened Philippines Plants and their Categories and the List of Other Wildlife Species), the National List of Threatened Philippine Plants and their categories, is hereby updated. Section 1. Definition of Terms. As used in this Order, the following terms shall mean as follows: a. CITES - refers to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, a treaty regulating international trade of fauna and flora listed in its Appendices; CITES Appendix I - species threatened with extinction, which are or may be affected by trade. International (commercial) trade in wild-taken specimens is generally prohibited. CITES Appendix II -species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but for which trade must be controlled to avoid their becoming so, and species that resemble species already included in Appendix II. International trade is permitted but regulated through appropriate permits/certificates. CITES Appendix III - species included at the request of a Party that already regulates trade in the species and that needs the cooperation of other countries to prevent unsustainable or illegal exploitation. -

Lamiales – Synoptical Classification Vers

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.6.2 (in prog.) Updated: 12 April, 2016 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.6.2 (This is a working document) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, P. Beardsley, D. Bedigian, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, J. Chau, J. L. Clark, B. Drew, P. Garnock- Jones, S. Grose (Heydler), R. Harley, H.-D. Ihlenfeldt, B. Li, L. Lohmann, S. Mathews, L. McDade, K. Müller, E. Norman, N. O’Leary, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, D. Tank, E. Tripp, S. Wagstaff, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, A. Wortley, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and many others [estimated 25 families, 1041 genera, and ca. 21,878 species in Lamiales] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near- term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. -

Acteoside and Related Phenylethanoid Glycosides in Byblis Liniflora Salisb

Vol. 73, No. 1: 9-15, 2004 ACTA SOCIETATIS BOTANICORUM POLONIAE 9 ACTEOSIDE AND RELATED PHENYLETHANOID GLYCOSIDES IN BYBLIS LINIFLORA SALISB. PLANTS PROPAGATED IN VITRO AND ITS SYSTEMATIC SIGNIFICANCE JAN SCHLAUER1, JAROMIR BUDZIANOWSKI2, KRYSTYNA KUKU£CZANKA3, LIDIA RATAJCZAK2 1 Institute of Plant Biochemistry, University of Tübingen Corrensstr. 41, 72076 Tübingen, Germany 2 Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medical Sciences in Poznañ w. Marii Magdaleny 14, 61-861 Poznañ, Poland 3 Botanical Garden, University of Wroc³aw Sienkiewicza 23, 50-335 Wroc³aw, Poland (Received: May 30, 2003. Accepted: February 4, 2004) ABSTRACT From plantlets of Byblis liniflora Salisb. (Byblidaceae), propagated by in vitro culture, four phenylethanoid glycosides acteoside, isoacteoside, desrhamnosylacteoside and desrhamnosylisoacteoside were isolated. The presence of acteoside substantially supports a placement of the family Byblidaceae in order Scrophulariales and subclass Asteridae. Moreover, the genera containing acteoside are listed; almost all of them appear to belong to the order Scrophulariales. KEY WORDS: Byblis liniflora, Byblidaceae, Scrophulariales, chemotaxonomy, phenylethanoid gly- cosides, acteoside, in vitro propagation. INTRODUCTION et Conran, B. filifolia Planch, B. rorida Lowrie et Conran, and B. lamellata Conran et Lowrie. Byblidaceae are a small family of essentially Western Byblis liniflora Salisb. grows erect to 15-20 cm. Its lea- and Northern Australian (extending to Papuasia) herbs ves are alternate, involute in vernation, simple, linear with with exstipulate, linear sticky leaves spirally arranged a clavate apical swelling, and with stipitate, adhesive and along a more or less upright or sprawling stem and solita- sessile, digestive glands on the lamina (Huxley et al. 1992; ry, ebracteolate, pentamerous, weakly sympetalous, very Lowrie 1998). -

P;J/AI1)~!Jp/L

~. p;J/AI1) ~!Jp/l \II ~iJIO.IYO-r.?(}) l .._ A REVIEW AND ASSESSMENT OF THE FLORISTIC KNOWLEDGE OF SAMAR ISLAND Based on literature, PNH Records and Current Knowledge' ..l ..I .., USAID ******* 'I.; , I:,•• A REVIEW AND ASSESSMENT OF THE FLORISTIC KNOWLEDGE OF SAMAR ISLAND Based on literature, PNH Records and Current Knowledge' by DOMINGO A. MADUUD' Specialist for Flora November 30, 2000 Samar Island Biodiversity Study (SAMBIO) Resources, Environment and Economics Center for Studies, Inc. (REECS) In association with Orient Integrated Development Consultants, Inc. (OIDCI) Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) I This publication was made possible through support provided by the U. S. Agency for International Development, under the terms of Grant No. 492-G-OO-OO-OOOOT-OO. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U. S. Agency for International DevelopmenL 2 The author, Dr. Domingo Madulid, is the Floristic Assessment Specialist of SAMBIO, REECS. / TABLE OF CONTENTS List ofTables Executive Summary.................................................................................... iv 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 2. METHODOLOGy . 2 2.1 Brief Historical Account of Botanical Explorations in Samar (based on records of the Philippine National Herbarium) . 2 3. BOTANICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF SAMAR ISLAND.............................. 5 3.1 Rare, Endangered, Endemic, and Useful Plants of Samar................ 5 3.2 Vegetation Types in Samar Island............................................. 7 4. ASSESSMENT OF BOTANICAL INFORMATION AVAILABLE............... 8 4.1 Plant Diversity Assessment Inside the Forest Resource Assessment Transect Lines........................................................................ 9 4.2 List of Threatened Plants Found in the Transect Plots and Adjoining Areas...................................................................... 10 1iIII. 4.3 Species Diversity of Economic Plants from the Transect.............. -

Gogoi P, Nath N. Diversity and Inventorization of Angiospermic Flora in Dibrugarh District, Assam, Northeast India. Plant Science Today

1 Gogoi P, Nath N. Diversity and inventorization of angiospermic flora in Dibrugarh district, Assam, Northeast India. Plant Science Today. 2021;8(3):621–628. https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.2021.8.3.1118 Supplementary Tables Table 1. Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG IV) Classification of angiosperm taxa from Dibrugarh District. Families according to B&H Superorder/Order Family and Species System along with family Common name Habit Nativity Uses number BASAL ANGIOSPERMS APG IV Nymphaeales Nymphaeaceae Nymphaea nouchali 8.Nymphaeaceae Boga-bhet Aquatic Herb Native Edible Burm.f. Nymphaea rubra Roxb. Mokua/ Ronga 8.Nymphaeaceae Aquatic Herb Native Medicinal ex Andrews bhet MAGNOLIIDS Piperales Saururaceae Houttuynia cordata 139.(A) Mosondori Herb Native Medicinal Thunb. Saururaceae Piperaceae Piper longum L. 139.Piperaceae Bon Jaluk Climber Native Medicinal Piper nigrum L. 139.Piperaceae Jaluk Climber Native Medicinal Piper thomsonii (C.DC.) 139.Piperaceae Aoni pan Climber Native Medicinal Hook.f. Peperomia mexicana Invasive/ 139.Piperaceae Pithgoch Herb (Miq.) Miq. SAM Aristolochiaceae Aristolochia ringens Invasive/ 138.Aristolochiaceae Arkomul Climber Medicinal Vahl TAM Magnoliales Magnolia griffithii 4.Magnoliaceae Gahori-sopa Tree Native Wood Hook.f. & Thomson Magnolia hodgsonii (Hook.f. & Thomson) 4.Magnoliaceae Borhomthuri Tree Native Cosmetic H.Keng Magnolia insignis Wall. 4.Magnoliaceae Phul sopa Tree Native Magnolia champaca (L.) 4.Magnoliaceae Tita-sopa Tree Native Medicinal Baill. ex Pierre Magnolia mannii (King) Figlar 4.Magnoliaceae Kotholua-sopa Tree Native Annonaceae Annona reticulata L. 5.Annonaceae Atlas Tree Native Edible Annona squamosa L. 5.Annonaceae Atlas Tree Invasive/WI Edible Monoon longifolium Medicinal/ (Sonn.) B. Xue & R.M.S. 5.Annonaceae Debodaru Tree Exotic/SR Biofencing Saunders Laurales Lauraceae Actinodaphne obovata 143.Lauraceae Noga-baghnola Tree Native (Nees) Blume Beilschmiedia assamica 143.Lauraceae Kothal-patia Tree Native Meisn.