Iiliij Nitumon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Badjaos in Tawi- Tawi, Southwest Philippines Erwin Rapiz Navarro

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Living by the Day: A Study of the Badjaos in Tawi- Tawi, Southwest Philippines Erwin Rapiz Navarro Master’s thesis in Peace and Conflict Transformation – November 2015 i Abstract This study examines the impacts of sedentarization processes to the Badjaos in Tawi-Tawi, southwest of the Philippines. The study focuses on the means of sedentarizing the Badjaos, which are; the housing program and conditional cash transfer fund system. This study looks into the conditionalities, perceptions and experiences of the Badjaos who are beneficiaries of the mentioned programs. To realize this objective, this study draws on six qualitative interviews matching with participant-observation in three different localities in Tawi-Tawi. Furthermore, as a conceptual tool of analysis, the study uses sedentarization, social change, human development and ethnic identity. The study findings reveal the variety of outcomes and perceptions of each program among the informants. The housing project has made little impact to the welfare of the natives of the region. Furthermore, the housing project failed to provide security and consideration of cultural needs of the supposedly beneficiaries; Badjaos. On the other hand, cash transfer fund, though mired by irregularities, to some extent, helped in the subsistence of the Badjaos. Furthermore, contentment, as an antithesis to poverty, was being highlighted in the process of sedentarization as an expression of ethnic identity. Analytically, this study brings substantiation on the impacts of assimilation policies to indigenous groups, such as the Badjaos. Furthermore, this study serves as a springboard for the upcoming researchers in the noticeably lack of literature in the study of social change brought by sedentarization and development policies to ethnic groups in the Philippines. -

Diocese of Richmond Retired: Rt

618 RENO P.O. Box 325. Winnemucca, Humboldt Co., St. Paul's, Rev. Absent on leave: Revs. Joseph Azzarelli, Dio Missions—Beatty, St Theresa, Round George B. Eagleton, V.F. cese of Scranton; Edward O. Cassidy, So Mountain. P.O. Box 93. ciety of St. James the Apostle, working in Latin America, Charles W. Paris. Stations—Fish Lake Valley, Goldfield. Missions—St. Alphonsus', Paradise Valley, Diocese of Richmond Retired: Rt. Rev. Msgrs. Luigi Roteglia, Virginia City, Storey Co., St. Mary's in the Sacred Heart. McDermitt. Daniel B. Murphy, V.F., Henry J. M. (Dioecesis Richmondiensis) Mountains, Rev. Caesar J. Caviglia. Yerington, Lyon Co., Holy Family, Rev. Hu- Wientjes, Revs. Timothy 0. Ryan, Michael P.O. Box 384. [CEM] burt A Buel. O'Meara. Mission—Dayton. P.O. Box 366. On duty outside the diocese: Revs. William T. Mission—St John the Baptist, Smith Val Condon, Urban S. Konopka, Chaps. U. S. Wells. Elko Co., St Thomas Aquinas, Rev. ley. Army; Raymond Stadia, Chap. U. S. Air Thomas J. Miller. Force; Willy Price, Ph.D., Faculty of the P.O. Box 371. University of Indiana, Bloomington, Ind. ESTABLISHED IN 1820. Square Miles = Virginia, INST1T U TIONS OF THE DIOCESE 31,590; West Virginia, 3.486; = 36,076. HIGH SCHOOLS, DIOCESAN CONVENTS AND RESIDENCES FOR further information regarding the Community SISTEBS may be found. Comprises the State of Virginia, with the ex RENO. Bishop Manogue Catholic High School C.S.V. [64]—Clerics of St. Viator.—Las Vegas: Most Reverend ception of the Counties of Accomac, Northamp —400 Bartlett st—Rev. -

State Congregation Country Website Cong Belgium A14 Gasthuiszers Augustinessen B ‐ 3290 Diest France Adoration Reparatrice F ‐ 75005 Paris India Adoration Srs

STATE CONGREGATION COUNTRY WEBSITE_CONG BELGIUM A14 GASTHUISZERS AUGUSTINESSEN B ‐ 3290 DIEST FRANCE ADORATION REPARATRICE F ‐ 75005 PARIS INDIA ADORATION SRS. OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT ALWAYE,KERALA 683.102 ARGENTINA ADORATRICES DEL SMO. SACRAMENTO 1061 BUENOS AIRES MEXICO ADORATRICES PERPETUAS GUADALUPANAS 04010 MEXICO D.F. ITALIA ADORATRICI DEL SS. SACRAMENTO 26027 RIVOLTA D'ADDA CR www.suoreadoratrici.it UNITED KINGDOM ADORERS OF THE SACRED HEART GB ‐ LONDON W2 2LJ U.S.A. ADRIAN DOMINICAN SISTERS ADRIAN, MI 49221‐1793 MEXICO AGUSTINAS DE NUESTRA SEÑORA DEL SOCORRO 03920 MEXICO D.F. ESPAÑA AGUSTINAS HERMANAS DELAMPARO BALEARES PORTUGAL ALIANÇA DE SANTA MARIA 4800‐443 GUIMARÃES www.aliancadesantamaria.com PUERTO RICO AMISTAD MISIONERA EN CRISTO OBRERO SAN JUAN 00912‐3601 ITALIA ANCELLE DEL S. CUORE DI GESU' 40137 BOLOGNA BO ROMA ANCELLE DEL S. CUORE DI GESU' 00188 ROMA RM www.ancellescg.it ITALIA ANCELLE DEL SACRO CUORE DELLA VEN. C. VOLPICELLI 80137 NAPOLI NA ROMA ANCELLE DELLA BEATA VERGINE MARIA IMMACOLATA 00191 ROMA RM ITALIA ANCELLE DELLA CARITA' 25100 BRESCIA BS ROMA ANCELLE DELLA VISITAZIONE 00161 ROMA RM www.ancelledellavisitazione.org ROMA ANCELLE DELL'AMORE MISERICORDIOSO 00176 ROMA RM ITALIA ANCELLE DELL'IMMACOLATA DI PARMA 43123 PARMA PR ITALIA ANCELLE DELL'INCARNAZIONE 66100 ‐ CHIETI CH ITALIA ANCELLE DI GESU' BAMBINO 30121 VENEZIA VE ROMA ANCELLE FRANCESCANE DEL BUON PASTORE 00166 ROMA RM POLAND ANCELLE IMMACOLATA CONCEZIONE B. V. MARIA PL ‐ 62‐031 LUBON 3 ROMA ANCELLE MISSIONARIE DEL SS. SACRAMENTO 00135 ROMA RM www.ancellemisionarie.org ITALIA ANCELLE RIPARATRICI 98121 MESSINA ME CHILE APOSTOLADO POPULAR DEL SAGRADO CORAZON CONCEPCION ‐ VIII ROMA APOSTOLE DEL SACRO CUORE DI GESU' 00185 ROMA RM www.apostole.it INDIA APOSTOLIC CARMEL GENERALATE BANGALORE 560.041 ‐ KARNATAKA ESPAÑA APOSTOLICAS DEL CORAZON DE JESUS MADRID 28039 GERMANY ARME DIENSTMAEGDE JESU CHRISTI D ‐ 56428 DERNBACH www.phjc‐generalate.org GERMANY ARME FRANZISKANERINNEN V. -

The Filipino Express V32 Issue 41

VOL. 32 w NO. 41 w October 5-11, 2018 w NATIONAL EDITION w NEW JERSEY w NEW YORK w 201-434-1114 Possible 'growth' seen in Duterte's digestive tract after test PALACE TO RELEASE PRESIDENT'S MEDICAL BULLETIN IF IT'S CRITICAL By Nestor Corrales The result of the endoscopy of President Rodrigo Duterte showed a possible “growth” in his digestive tract that prompted him to make further examinations, Malacanang said Friday, Oct. 5. Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said Duterte revealed about the result of his endoscopy during the joint command conference of the police and the military u Pa inge 6 Filipino home care workers win as LA city attorney settles wage theft case Page 4 NY Times: Trump got 413M from his dad, much from tax dodges Page 7 Trump’s new proposal on public aid triggers panic among immigrants Page 9 Los Angeles City Attorney with victorious Filipino home care workers. LA CA WEBSITE Bans galore await tourists when Boracay reopens Page 2 Tuna catchers decry raw deal on payment Reds recruiting in 18 schools Page 20 for oust-Duterte plot - AFP By Jeannette I. Andrade A senior military officer on Wednesday, Oct. 3, warned that communist rebels were recruiting students from some of the country's top universities to join a plot to oust President Rodrigo Duterte so they could establish a dictatorship similar to the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia that killed millions of its own people. Brig. Gen. Antonio Parlade Jr., assistant deputy chief of staff for operations of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, told reporters that the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing, the New People's Army (NPA), had infiltrated 18 schools in Golden girls: US wins 3rd straight women’s Metro Manila, including De La Salle University (DLSU) and Ateneo de Manila University hoops World Cup Page 28 u Page 6 October 5-11, 2018 Page 2 THE FILIPINO EXPRESS Bans galore await tourists when Boracay reopens By Nestor P. -

Company Registration and Monitoring Department

Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance Securities and Exchange Commission SEC Building, EDSA, Greenhills, Mandaluyong City Company Registration and Monitoring Department LIST OF CORPORATIONS WITH APPROVED PETITIONS TO SET ASIDE THEIR ORDER OF REVOCATION SEC REG. HANDLING NAME OF CORPORATION DATE APPROVED NUMBER OFFICE/ DEPT. A199809227 1128 FOUNDATION, INC. 1/27/2006 CRMD A199801425 1128 HOLDING CORPORATION 2/17/2006 CRMD 3991 144. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL INC. 2/27/2009 CRMD 12664 18 KARAT, INC. 11/24/2005 CRMD A199906009 1949 REALTY CORPORATION 3/30/2011 CRMD 153981 1ST AM REALTY AND DEVLOPMENT CORPORATION 5/27/2014 CRMD 98097 20th Century Realty Devt. Corp. 3/11/2008 OGC A199608449 21st CENTURY ENTERTAINMENT, INC. 4/30/2004 CRMD 178184 22ND CENTURY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 7/5/2011 CRMD 141495 3-J DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 2/3/2014 CRMD A200205913 3-J PLASTICWORLD & DEVELOPMENT CORP. 3/13/2014 CRMD 143119 3-WAY CARGO TRANSPORT INC. 3/18/2005 CRMD 121057 4BS-LATERAL IRRIGATORS ASSN. INC. 11/26/2004 CRMD 6TH MILITARY DISTRICT WORLD WAR II VETERANS ENO9300191 8/16/2004 CRMD (PANAY) ASSOCIATION, INC. 106859 7-R REALTY INC. 12/12/2005 CRMD A199601742 8-A FOOD INDUSTRY CORP. 9/23/2005 CRMD 40082 A & A REALTY DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES, INC. 5/31/2005 CRMD 64877 A & S INVESTMENT CORPORATION 3/7/2014 CRMD A FOUNDATION FOR GROWTH, ORGANIZATIONAL 122511 9/30/2009 CRMD UPLIFTMENT OF PEOPLE, INC. (GROUP) GN95000117 A HOUSE OF PRAYER FOR ALL NATIONS, INC. CRMD AS095002507 A&M DAWN CORPORATION 1/19/2010 CRMD A. RANILE SONS REALTY DEVELOPMENT 10/19/2010 CRMD A.A. -

Oblación Y Martirio”

Editores: Fabio Ciar- Studia 8 di, omi y Alberto Ruiz González, omi; ellos son, respectivamente, el Director del Servicio General de Estudios Oblatio Oblatio Studia 8 Oblatos y el Vicepro- vincial de la Provincia Mediterránea. Juntos organizaron y dirigie- ron la Conferencia sobre “Oblación y martirio”. En este volumen se pu- blican sus Actas. El Servicio General de Estudios Oblatos, de acuerdo con la Postulación General y la Provincia Mediterránea, organizó en Pozuelo, del 4 al 5 de mayo de 2019, una Conferencia sobre “Oblación y martirio”, con un triple propósito: reflexionar sobre el vínculo íntimo entre oblación y martirio; estudiar de cerca la historia de los mártires oblatos de España; iniciar un estudio sistemático sobre el martirio de los oblatos en los diferentes conti- nentes, a partir de algunos ejemplos significativos para cada región. Le Service général des études oblates, d’accord avec la Postulation généra- le et la Province méditerranéenne, du 4 au 5 mai 2019, à Pozuelo, Madrid, a organisé cette conférence sur « l’Oblation et le martyre » dans un triple objectif: réfléchir sur le lien intime entre l’oblation et le martyre; étudier de près l’histoire des martyrs Oblats d’Espagne; commencer une étude systé- Fabio Ciardi, omi matique sur le martyre des Oblats sur différents continents, en se basant sur y Alberto Ruiz González, omi (editores) des exemples significatifs pour chaque région. Oblación y Martirio The General Service of Oblate Studies, in agreement with the General Pos- Oblation et Martyre – and Martyrdom tulation -

Christ's Shepherd Among the Disciples

CHRIST’S SHEPHERD AMONG THE DISCIPLES: RE-EXPLORING FORMATION MINISTRY’S SCRIPTURAL, PHILOSOPHICAL, AND THEOLOGICAL GROUNDING IN THE PHILIPPINE CONTEXT by Fr. Jaime Del Rosario, OMI, DMin 1 CHRIST’S SHEPHERD AMONG THE DISCIPLES: RE-EXPLORING FORMATION MINISTRY’S SCRIPTURAL, PHILOSOPHICAL, AND THEOLOGICAL GROUNDING IN THE PHILIPPINE CONTEXT by Fr. Jaime Del Rosario, OMI, DMin The dwindling number of Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) college-level seminarians in the Philippines proceeding to their novitiate prompted this researcher’s study of both the situation of these seminarians and contextualizing scriptural, philosophical, and theological principles for a ministerial response. The Pastoral Situation and Method of the Study The aforementioned formands begin with a good number in their first-year in the college-level seminary ranging from fifteen to forty-five freshmen formands in the recent five academic years since 2010. About a quarter of this number continue unto their senior college seminary year and a postulancy year after their college graduation; but those entering the novitiate after postulancy from each of these classes ranged from 0 for two consecutive academic years to 1 to 2 novices for the more recent three years. The contemporary Filipino young persons’ characteristics strongly influence the OMI college-level seminarians themselves, based on what these formands usually narrate of their seminary formative experience for decision-making whether to proceed further into the next stages of the OMI seminary formation. What are -

B Taxes ~ AUG 21 2 ~ 91 941

V MB Ho 7545-0052 Form ~ fnt'tturn of Private Fot]!!iciafwn 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust DepatmmtallneTressry Treated as a Private Foundation Manias Rmsiua sake Note The organization may be able to use a copy of this ietum to sahsly state repor LUOZ Forcalendar Year 2002.ortexYear becmmna APR 1 . 2002 .andendmo MAT Name of organization Employer number Use the IRS Identification label otherwise, OCH FOUNDATION INC . »-ioo» print NumEsir and street (v P 0 DOa numUt it mYl is not ENrveW to street aculress) hiynt- B Telephone number °'hpe 2830 NW 41ST STREET SUITE H lJ7L/J/J-/Y71 Sea Specific town, u uanotim mo1raoon is onaoo clien, has Instructions City or state, and ZIP code Mil. El AINESVILLE FL 32606-6667 t Foreign organizations, check here No. Foreign vpani~t~onsmsstinpVie85%imt , H Check type of organization Ex] Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation Cnq~ nIa ana attach computabm If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method LXJ Cash U Accrual under section 507(6)(7)(A), check here "0 (from Part II, col (c), line 16) EDOther (specify) If the foundation is in a 60-month termination S 10 9 8 7 2 5 7 9 . (Pan i, column (d) must be on cash bass under section 507(b ) 1 )~B), check here Part I Analyse of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (d) oisou« .nte (rlistotyof emounisinrowmns(tA(c)ana(a) ay hot (c) Adjusted net for cnameis,o~ nxwIlYeuame mountainmWmnlal) expenses per books income income 1 Contributions, gins, grants, etc, received 9 , 3 69 . -

April 2012 a Publication of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Victoria

See Page 12 See Page 24 See Page 21 50th School Feature Holy Week International Queen of Angels Mass Schedule Eucharistic Congress The Diocesan MessengerApril 2012 A Publication of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Victoria I See His Blood upon the Rose By Joseph Mary Plunkett (1887–1916) I see his blood upon the rose And in the stars the glory of his eyes, His body gleams amid eternal snows, His tears fall from the skies. I see his face in every flower; The thunder and the singing of the birds Are but his voice—and carven by his power Rocks are his written words. All pathways by his feet are worn, His strong heart stirs the ever-beating sea, His crown of thorns is twined with every thorn, His cross is every tree. Canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Statement by the President of the Canadian Conference Of Catholic Bishops Welcoming The Canonization of Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha Inside It is with great joy that the Bishops of Canada welcome the February 18, 2012 announcement that our Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, will canonize Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, elevating her to sainthood. This event will be a great honour to all of North America, but also in a particular way to its Aboriginal Peoples, of whom Kateri will be the first to receive this dignity. Appeal in Action ............ 2 Blessed Kateri, known as “the Lily of the Mohawks”, was born in 1656 in what is now New York State. Persecuted for the Calendar of Events .......... 4 Catholic faith she held so tenaciously, she moved to a Christian Mohawk village in what is now Kahnawake, within the current diocese of Saint-Jean Longueuil, Quebec, where she died at the age of 24. -

Directory of Swdas Valid

List of Social Welfare and Development Agencies (SWDAs) with VALID REGISTRATION, LICENSED TO OPERATE AND ACCREDITATION CERTIFICATES per AO 17 s. 2008 as of January 11, 2012 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration Licens Accred. # Programs and Services Service Clientele Area(s) of Address /Tel-Fax Nos. Person # e # Delivery Operation Mode NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Children & Youth Welfare (Residential) A HOME FOR THE ANGELS Mrs. Ma. DSWD-NCR-RL- SB-2008-100 adoption and foster care, homelife, Residentia 0-6 months old NCR CHILD CARING FOUNDATION, Evelina I. 000086-2011 September 23, social and health services l Care surrendered, INC. Atienza November 21, 2011 2008 to abandoned and 2306 Coral cor. Augusto Francisco Executive to November 20, September 22, foundling children Sts., Director 2014 2011 San Andres Bukid, Manila Tel. #: 562-8085 Fax#: 562-8089 e-mail add:[email protected] ASILO DE SAN VICENTE DE Sr. Nieva C. DSWD-NCR RL- DSWD-SB-A- temporary shelter, homelife services, Residentia residential care -5- NCR PAUL Manzano 000032-2010 000409-2010 social services, psychological services, l care and 10 years old (upon No. 1148 UN Avenue, Manila Administrator July 16, 2010 to July September 20, primary health care services, educational community- admission) Tel. #: 523-3829/523-5264; 522- 15, 2013 2010 to services, supplemental feeding, based neglected, 6898/522-1643 September 19, vocational technology program surrendered, Fax # 522-8696 2013 (commercial cooking, food and abandoned, e-mail add: [email protected] (Residential beverage, transient home) emergency physically abused, care) relief streetchildren - vocational DSWD-SB-A- technology progrm 000410-2010 - youth 18 years September 20, old above 2010 to - transient home- September 19, financially hard up, 2013 no relative in (Community Manila based) Page 1 of 332 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration Licens Accred. -

Interdisiplinaryong Journal Sa Edukasyong Pangkultura

2017, Tomo 2 Interdisiplinaryong Journal sa Edukasyong Pangkultura Talas: Interdisiplinaryong Journal sa Edukasyong Pangkultura 2017, Tomo 2 Karapatang-ari @ 2017 Pambansang Komisyon para sa Kultura at mga Sining at Philippine Cultural Education Program Pambansang Komisyon para sa Kultura at mga Sining Philippine Cultural Education Program Room 5D #633 General Luna Street, Inramuros, Maynila Telepono: (02) 527-2192, lokal 529 Email: [email protected] BACH Institute, Inc. Bulacan Arts Culture and History Institute 2nd Floor, Gat Blas Ople Building Sentro ng Sining at Kultura ng Bulacan Bulacan Provincial Capitol, Complex Malolos City, Bulacan 3000 The National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) is the overall coordination and policy making government body that systematizes and streamlines national efforts in promoting culture and the arts. The NCCA promotes cultural and artistic development: conserves and promotes the nation’s historical and cultural heritages; ensures the widest dissemination of artistic and cultural products among the greatest number across the country; preserves and integrates traditional culture and its various expressions as dynamic part of the national cultural mainstream; and ensures that standards of excellence are pursued in programs and activities. The NCCA administers the National Endowment Fund for Culture and the Arts (NEFCA). Hindi maaaring kopyahin ang alinmang bahagi ng aklat sa alinmang paraan—grapiko, elektroniko, mekanikal—nang walang nakasulat na pahintulot mula sa mga may hawak ng karapatang-sipi. 5 Lupon ng EditorEditor Nilalaman Paunang Salita/Joseph “Sonny” Cristobal 7 Introduksiyon/Galileo S. Zafra 8 Joseph “Sonny” Cristobal Direktor, Philippine Cultural Education Program Mga Saliksik at Malikhaing Akda Pambansang Komisyon para sa Kultura at mga Sining Tagapaglathala I. -

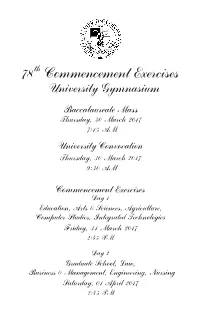

78Th Commencement Exercises

78th Commencement Exercises University Gymnasium Baccalaureate Mass Thursday, 30 March 2017 7:15 AM University Convocation Thursday, 30 March 2017 9:30 AM Commencement Exercises Day 1 Education, Arts & Sciences, Agriculture, Computer Studies, Integrated Technologies Friday, 31 March 2017 2:45 PM Day 2 Graduate School, Law, Business & Management, Engineering, Nursing Saturday, 01 April 2017 2:45 PM Baccalaureate Mass Presider & Preacher ANTONIO J LEDESMA SJ DD Archbishop of Cagayan de Oro University Convocation Processional National Anthem XAVIER UNIVERSITY GLEE CLUB Declaration of Opening RENE C TACASTACAS SJ of Convocation Academic Vice President Valedictory Address BRIAN ADAM S ANAY, Cum Laude Bachelor of Science in Development Communication Conferring of University Awards Archbishop Santiago TG Hayes SJ Awardee DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY OF ST VINCENT DE PAUL Servants of Christ's Mission in the Peripheries of Mindanao Response DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY OF ST VINCENT DE PAUL Represented by Provincial Councillor Sr Neriza Herbon DC Fr Francisco R Demetrio SJ Awardee SR MA DELIA CORONEL ICM Folklorist and Interfaith Dialogue Advocate Response SR MA DELIA CORONEL ICM Represented by Sr Amelia David ICM, Provincial Superior Choral Tribute XAVIER UNIVERSITY GLEE CLUB Conferring of Honorary Doctorate BR CARLITO "KARL" GASPAR CSSR Author, Interfaith Scholar, and Mindanaon Socio-anthropologist Address to the Graduates BR CARLITO "KARL" GASPAR CSSR Closing Remarks ROBERTO C YAP SJ University President Master of Ceremonies LILIA A COTEJAR MA Assistant Professor,