Console Games in the Age of Convergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imperial College London Department of Physics Graphene Field Effect

Imperial College London Department of Physics Graphene Field Effect Transistors arXiv:2010.10382v2 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 20 Jul 2021 By Mohamed Warda and Khodr Badih 20 July 2021 Abstract The past decade has seen rapid growth in the research area of graphene and its application to novel electronics. With Moore's law beginning to plateau, the need for post-silicon technology in industry is becoming more apparent. Moreover, exist- ing technologies are insufficient for implementing terahertz detectors and receivers, which are required for a number of applications including medical imaging and secu- rity scanning. Graphene is considered to be a key potential candidate for replacing silicon in existing CMOS technology as well as realizing field effect transistors for terahertz detection, due to its remarkable electronic properties, with observed elec- tronic mobilities reaching up to 2 × 105 cm2 V−1 s−1 in suspended graphene sam- ples. This report reviews the physics and electronic properties of graphene in the context of graphene transistor implementations. Common techniques used to syn- thesize graphene, such as mechanical exfoliation, chemical vapor deposition, and epitaxial growth are reviewed and compared. One of the challenges associated with realizing graphene transistors is that graphene is semimetallic, with a zero bandgap, which is troublesome in the context of digital electronics applications. Thus, the report also reviews different ways of opening a bandgap in graphene by using bi- layer graphene and graphene nanoribbons. The basic operation of a conventional field effect transistor is explained and key figures of merit used in the literature are extracted. Finally, a review of some examples of state-of-the-art graphene field effect transistors is presented, with particular focus on monolayer graphene, bilayer graphene, and graphene nanoribbons. -

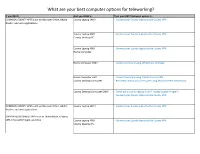

What Are Your Best Computer Options for Teleworking?

What are your best computer options for teleworking? If you NEED… And you HAVE a… Then your BEST telework option is… COMMON COUNTY APPS such as Microsoft Office, Adobe County Laptop ONLY - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Reader, and web applications County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN County Desktop PC County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Home Computer Home Computer ONLY - Connect remotely using VDI (Virtual Desktop) Home Computer AND - Connect remotely using Dakota County VPN County Desktop Computer - Remotely control your computer using Windows Remote Desktop County Desktop Computer ONLY - Check out a County laptop from IT Laptop Loaner Program - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN COMMON COUNTY APPS such as Microsoft Office, Adobe County Laptop ONLY - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Reader, and web applications SUPPORTED BUSINESS APPS such as OneSolution, OnBase, SIRE, Microsoft Project, and Visio County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN County Desktop PC If you NEED… And you HAVE a… Then your BEST telework option is… County Laptop AND - Connect your County laptop to the County VPN Home Computer Home Computer ONLY - Contact the County IT Help Desk at 651/438-4346 Home Computer AND - Connect remotely using Dakota County VPN County Desktop Computer - Remotely control your computer using Windows Remote Desktop County Desktop Computer ONLY - Check out a County laptop from IT Laptop Loaner Program - Connect your County laptop -

Arithmetic and Logic Unit (ALU)

Computer Arithmetic: Arithmetic and Logic Unit (ALU) Arithmetic & Logic Unit (ALU) • Part of the computer that actually performs arithmetic and logical operations on data • All of the other elements of the computer system are there mainly to bring data into the ALU for it to process and then to take the results back out • Based on the use of simple digital logic devices that can store binary digits and perform simple Boolean logic operations ALU Inputs and Outputs Integer Representations • In the binary number system arbitrary numbers can be represented with: – The digits zero and one – The minus sign (for negative numbers) – The period, or radix point (for numbers with a fractional component) – For purposes of computer storage and processing we do not have the benefit of special symbols for the minus sign and radix point – Only binary digits (0,1) may be used to represent numbers Integer Representations • There are 4 commonly known (1 not common) integer representations. • All have been used at various times for various reasons. 1. Unsigned 2. Sign Magnitude 3. One’s Complement 4. Two’s Complement 5. Biased (not commonly known) 1. Unsigned • The standard binary encoding already given. • Only positive value. • Range: 0 to ((2 to the power of N bits) – 1) • Example: 4 bits; (2ˆ4)-1 = 16-1 = values 0 to 15 Semester II 2014/2015 8 1. Unsigned (Cont’d.) Semester II 2014/2015 9 2. Sign-Magnitude • All of these alternatives involve treating the There are several alternative most significant (leftmost) bit in the word as conventions used to -

FUNDAMENTALS of COMPUTING (2019-20) COURSE CODE: 5023 502800CH (Grade 7 for ½ High School Credit) 502900CH (Grade 8 for ½ High School Credit)

EXPLORING COMPUTER SCIENCE NEW NAME: FUNDAMENTALS OF COMPUTING (2019-20) COURSE CODE: 5023 502800CH (grade 7 for ½ high school credit) 502900CH (grade 8 for ½ high school credit) COURSE DESCRIPTION: Fundamentals of Computing is designed to introduce students to the field of computer science through an exploration of engaging and accessible topics. Through creativity and innovation, students will use critical thinking and problem solving skills to implement projects that are relevant to students’ lives. They will create a variety of computing artifacts while collaborating in teams. Students will gain a fundamental understanding of the history and operation of computers, programming, and web design. Students will also be introduced to computing careers and will examine societal and ethical issues of computing. OBJECTIVE: Given the necessary equipment, software, supplies, and facilities, the student will be able to successfully complete the following core standards for courses that grant one unit of credit. RECOMMENDED GRADE LEVELS: 9-12 (Preference 9-10) COURSE CREDIT: 1 unit (120 hours) COMPUTER REQUIREMENTS: One computer per student with Internet access RESOURCES: See attached Resource List A. SAFETY Effective professionals know the academic subject matter, including safety as required for proficiency within their area. They will use this knowledge as needed in their role. The following accountability criteria are considered essential for students in any program of study. 1. Review school safety policies and procedures. 2. Review classroom safety rules and procedures. 3. Review safety procedures for using equipment in the classroom. 4. Identify major causes of work-related accidents in office environments. 5. Demonstrate safety skills in an office/work environment. -

Video Games: Changing the Way We Think of Home Entertainment

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2005 Video games: Changing the way we think of home entertainment Eri Shulga Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Shulga, Eri, "Video games: Changing the way we think of home entertainment" (2005). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Video Games: Changing The Way We Think Of Home Entertainment by Eri Shulga Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Technology Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Copyright 2005 Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Thesis Approval Form Student Name: _ __;E=.;r....;...i S=-h;....;..;u;;;..;..lg;;i..;:a;;...__ _____ Thesis Title: Video Games: Changing the Way We Think of Home Entertainment Thesis Committee Name Signature Date Evelyn Rozanski, Ph.D Evelyn Rozanski /o-/d-os- Chair Prof. Andy Phelps Andrew Phelps Committee Member Anne Haake, Ph.D Anne R. Haake Committee Member Thesis Reproduction Permission Form Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Video Games: Changing the Way We Think Of Home Entertainment L Eri Shulga. hereby grant permission to the Wallace Library of the Rochester Institute of Technofogy to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. -

The Central Processing Unit(CPU). the Brain of Any Computer System Is the CPU

Computer Fundamentals 1'stage Lec. (8 ) College of Computer Technology Dept.Information Networks The central processing unit(CPU). The brain of any computer system is the CPU. It controls the functioning of the other units and process the data. The CPU is sometimes called the processor, or in the personal computer field called “microprocessor”. It is a single integrated circuit that contains all the electronics needed to execute a program. The processor calculates (add, multiplies and so on), performs logical operations (compares numbers and make decisions), and controls the transfer of data among devices. The processor acts as the controller of all actions or services provided by the system. Processor actions are synchronized to its clock input. A clock signal consists of clock cycles. The time to complete a clock cycle is called the clock period. Normally, we use the clock frequency, which is the inverse of the clock period, to specify the clock. The clock frequency is measured in Hertz, which represents one cycle/second. Hertz is abbreviated as Hz. Usually, we use mega Hertz (MHz) and giga Hertz (GHz) as in 1.8 GHz Pentium. The processor can be thought of as executing the following cycle forever: 1. Fetch an instruction from the memory, 2. Decode the instruction (i.e., determine the instruction type), 3. Execute the instruction (i.e., perform the action specified by the instruction). Execution of an instruction involves fetching any required operands, performing the specified operation, and writing the results back. This process is often referred to as the fetch- execute cycle, or simply the execution cycle. -

Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C

04 3677_CH03 6/3/03 12:30 PM Page 67 Chapter 3 THE EXPERTS • Sid Meier, Firaxis General Game Design: • Bill Roper, Blizzard North • Brian Reynolds, Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C. Shelley, Ensemble Studios • Peter Molyneux, Do you like to use some brains along with (or instead of) brawn Lionhead Studios when gaming? This chapter is for you—how to create breathtaking • Alex Garden, strategy games. And do we have a roundtable of celebrities for you! Relic Entertainment Sid Meier, Firaxis • Louis Castle, There’s a very good reason why Sid Meier is one of the most Electronic Arts/ accomplished and respected game designers in the business. He Westwood Studios pioneered the industry with a number of unprecedented instant • Chris Sawyer, Freelance classics, such as the very first combat flight simulator, F-15 Strike Eagle; then Pirates, Railroad Tycoon, and of course, a game often • Rick Goodman, voted the number one game of all time, Civilization. Meier has con- Stainless Steel Studios tributed to a number of chapters in this book, but here he offers a • Phil Steinmeyer, few words on game inspiration. PopTop Software “Find something you as a designer are excited about,” begins • Ed Del Castillo, Meier. “If not, it will likely show through your work.” Meier also Liquid Entertainment reminds designers that this is a project that they’ll be working on for about two years, and designers have to ask themselves whether this is something they want to work on every day for that length of time. From a practical point of view, Meier says, “You probably don’t want to get into a genre that’s overly exhausted.” For me, working on SimGolf is a fine example, and Gettysburg is another—something I’ve been fascinated with all my life, and it wasn’t mainstream, but was a lot of fun to write—a fun game to put together. -

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

Super Mario Galaxy 2 Dolphin Emulato Download Iso Free Download Full PC Games

super mario galaxy 2 dolphin emulato download iso Free Download Full PC Games. Free PC Games Download - Full Version PC Games Download from direct links with complete DLCs, Updates, Patches, Trainers, Keys, and Cracks guaranteed. Top Ad unit 728 × 90. Don't Miss This! Super Mario Galaxy 2 (PC)–Dolphin Emulator 32.bit & 64.bit. Release Date: May 23, 2010 Exclusively on: Wii E for Everyone Genre: Platformer Publisher: Nintendo Developer: Nintendo EAD Tokyo Local Play: 2 Co-op. Super Mario Galaxy 2, the sequel to the smash-hit galaxy-hopping original game, includes the amazing gravity-defying, physics-based exploration from the first game, but is loaded with entirely new galaxies and features to challenge and delight players. On some stages, Mario can pair up with his dinosaur buddy Yoshi and use his tongue to grab items and spit them back at enemies. Players can also have fun with new items such as a drill that lets our hero tunnel through solid rock. (fileserver 400MB/link) http://pro-links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_fs.1.html http://pro- links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_fs.2.html http://pro- links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_fs.3.html http://pro- links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_fs.4.html Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | (iMirror – megaupload) http://pro-links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_mu.1.html http://pro- links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_mu.2.html http://pro- links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_mu.3.html http://pro- links.co.cc/vault/071609/downloads/Super_Mario_Galaxy_2_mu.4.html Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | (Important) Dolphin Emulator Settings And For Super Mario Galaxy 2 And Instructions: http://www.fileserve.com/file/mwn3b58. -

Scaling the Digital Divide: Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement

Scaling the Digital Divide Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement J a c o b V i g d o r a n d H e l e n l a d d w o r k i n g p a p e r 4 8 • j u n e 2 0 1 0 Scaling the Digital Divide: Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement Jacob L. Vigdor [email protected] Duke University Helen F. Ladd Duke University Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 Basic Evidence on Home Computer Use by North Carolina Public School Students 5 Access to home computers 5 Access to broadband internet service 7 How Home Computer Technology Might Influence Academic Achievement 10 An Adolescent's time allocation problem 10 Adapting the rational model to ten-year-olds 13 Estimation strategy 14 The Impact of Home Computer Technology on Test Scores 16 Comparing across- and within-student estimates 16 Extensions and robustness checks 22 Testing for effect heterogeneity 25 Examining the mechanism: broadband access and homework effort 29 Conclusions 34 References 36 Appendix Table 1 39 i Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the William T. Grant Foundation and the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER), supported through Grant R305A060018 to the Urban Institute from the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education for research support. They wish to thank Jon Guryan, Jesse Shapiro, Tim Smeeding, Andrew Leigh, and seminar participants at the University of Michigan, the University of Florida, Cornell University, the University of Missouri‐ Columbia, the University of Toronto, Georgetown University, Harvard University, the University of Chicago, Syracuse University, the Australian National University, the University of South Australia, and Deakin University for helpful comments on earlier drafts. -

The Video Game Industry an Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective

The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Nik Shah T’05 MBA Fellows Project March 11, 2005 Hanover, NH The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Authors: Nik Shah • The video game industry is poised for significant growth, but [email protected] many sectors have already matured. Video games are a large and Tuck Class of 2005 growing market. However, within it, there are only selected portions that contain venture capital investment opportunities. Our analysis Charles Haigh [email protected] highlights these sectors, which are interesting for reasons including Tuck Class of 2005 significant technological change, high growth rates, new product development and lack of a clear market leader. • The opportunity lies in non-core products and services. We believe that the core hardware and game software markets are fairly mature and require intensive capital investment and strong technology knowledge for success. The best markets for investment are those that provide valuable new products and services to game developers, publishers and gamers themselves. These are the areas that will build out the industry as it undergoes significant growth. A Quick Snapshot of Our Identified Areas of Interest • Online Games and Platforms. Few online games have historically been venture funded and most are subject to the same “hit or miss” market adoption as console games, but as this segment grows, an opportunity for leading technology publishers and platforms will emerge. New developers will use these technologies to enable the faster and cheaper production of online games. The developers of new online games also present an opportunity as new methods of gameplay and game genres are explored. -

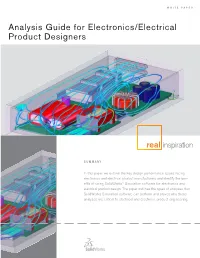

Analysis Guide for Electronics/Electrical Product Designers

WHITE PAPER Analysis Guide for Electronics/Electrical Product Designers inspiration SUMMARY In this paper we outline the key design performance issues facing electronics and electrical product manufacturers and identify the ben- efits of using SolidWorks® Simulation software for electronics and electrical product design. The paper outlines the types of analyses that SolidWorks Simulation software can perform and proves why these analyses are critical to electrical and electronic product engineering. Introduction Analysis and simulation software has become an indispensable tool for the development, certification, and success of electronics and electrical products. In addition to having to meet federal requirements, such as standards regulating electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) and product safety, electronics and electri- cal products manufacturers must meet various industry standards, such as the Bellcore standard for telecommunications equipment and standards governing the reliability of printed circuit boards (e.g., all PCBs must be able to withstand 21 pounds of load in the center). Combined with customer and market demand for smaller, more compact, and lighter products, these requirements create competitive pressures that make flawless, reliable development of electronics and electrical products an absolute necessity. FIGURE 1: THE USE OF CFD MAKES IT POSSIBLE TO ELIMINATE EXPENSIVE PHYS- IcaL PROTOTYpeS, AND FIND SERIOUS FLAWS MUCH eaRLIER IN THE deSIGN PROCESS. Today’s electronics/electrical product manufacturers use analysis software to simulate and assess the performance of a variety of product designs, including consumer electronics, appliances, sophisticated instrumentation, electronics components, printed circuit boards, RF equipment, motors, drives, electrical con- trols, micro electromechanical systems (MEMS), optical networking equipment, electronics packaging, and semiconductors. Analysis software enables engi- neers to simulate design performance and identify and address potential design problems before prototyping and production.