Preservation Education & Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Historic Landmark Nomination New

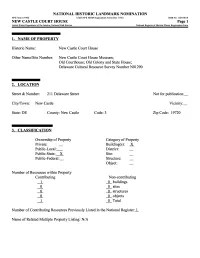

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: New Castle Court House Other Name/Site Number: New Castle Court House Museum; Old Courthouse; Old Colony and State House; Delaware Cultural Resource Survey Number NO 1290 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 211 Delaware Street Not for publication: City/Town: New Castle Vicinity:_ State: DE County: New Castle Code: 3 Zip Code: 19720 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): JL Public-Local:__ District: _ Public-State:_X. Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Non-contributing 1 0 buildings 0 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, N ational Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Black Evangelicals and the Gospel of Freedom, 1790-1890

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 Alicestyne Turley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turley, Alicestyne, "SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890" (2009). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 79. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/79 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Alicestyne Turley The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 _______________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _______________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Alicestyne Turley Lexington, Kentucky Co-Director: Dr. Ron Eller, Professor of History Co-Director, Dr. Joanne Pope Melish, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2009 Copyright © Alicestyne Turley 2009 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 The true nineteenth-century story of the Underground Railroad begins in the South and is spread North by free blacks, escaping southern slaves, and displaced, white, anti-slavery Protestant evangelicals. This study examines the role of free blacks, escaping slaves, and white Protestant evangelicals influenced by tenants of Kentucky’s Second Great Awakening who were inspired, directly or indirectly, to aid in African American community building. -

Special Master Report Appendices

No. 134, Original ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States ---------------------------------♦ --------------------------------- STATE OF NEW JERSEY, Plaintiff, v. STATE OF DELAWARE, Defendant. ---------------------------------♦ --------------------------------- REPORT OF THE SPECIAL MASTER APPENDICES ---------------------------------♦ --------------------------------- RALPH I. LANCASTER, JR. Special Master April 12, 2007 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page APPENDIX A: Proposed Decree ....................................A-1 APPENDIX B: Compact of 1905 ....................................B-1 APPENDIX C: Joint Statement of Facts.......................C-1 APPENDIX D: Order on New Jersey’s Motion to Strike Proposed Issues of Fact .................................... D-1 APPENDIX E: New Jersey’s Index of Evidentiary Materials........................................................................E-1 APPENDIX F: Delaware’s Index of Evidentiary Materials........................................................................F-1 APPENDIX G: New Jersey’s Proposed Decree............. G-1 APPENDIX H: Delaware’s Proposed Form of Judgment ...................................................................... H-1 APPENDIX I: Table of Actions by Delaware and New Jersey Reflecting an Assertion of Jurisdic tion or Authority Over the Eastern Shore of the Delaware -

The Dover Plan from the People – for the People

The Dover Plan From the People – For the People City of Dover, Delaware 2008 Comprehensive Plan Prepared by the City of Dover Department of Planning Adopted by the Dover City Council February 9, 2009 Adopted by the Dover Planning Commission December 2, 2008 Certified by the State of Delaware April 24, 2009 The Dover Plan From the People – For the People Acknowledgements Mayor: Carleton E. Carey, Sr. City Manager: Anthony J. DePrima, AICP City Council: Kenneth L. Hogan Planning Commission: John Friedman Thomas J. Leary William J. DiMondi James G. McGiffin John H. Baldwin, Sr. William P. McGlumphy Thomas Holt Eugene B. Ruane Francis C. Nichols Sophia R. Russell Michael von Reider Reuben Salters Ronald Shomo Timothy Slavin Fred Tolbert Beverly Williams Colonel Robert D. Welsh City of Dover Historic District Commission: C. Terry Jackson, II Joseph McDaniel James D. McNair, II Charles A. Salkin Ret. Col. Richard E. Scrafford The 2008 Dover Comprehensive Plan Project Team: City of Dover Planning Staff: Ann Marie Townshend, AICP, Director of Planning & Inspections Dawn Melson-Williams, AICP, Principal Planner Janelle Cornwell, AICP, Planner II Michael Albert, AICP, Planner Diane Metsch, Secretary II City of Dover Public Services: Scott Koenig, P.E., Director of Public Services Tracy Harvey, Community Development Manager City of Dover Public Utilities: Sharon Duca, P.E., Water/Wastewater Manager Steve Enss, Engineering Services & System Operations Supervisor City of Dover GIS Staff: Mark Nowak, GIS Coordinator Jeremy Gibb, GIS Technician City of Dover Parks & Recreation: Zachery C. Carter, Director University of Delaware: Asma Manejwala, Graduate Research Assistant City of Dover Economic Development Strategy Committee: Anthony J. -

John Hunn and the Underground Railroad in Southern Delaware by Justin Wilson John Hunn (1818-1894), Son of Ezekiel Hunn from Kent County, Delaware

The Quaker Hill Quill Quaker Hill Historic Preservation Foundation Vol. V, Number 2, May, 2016 521 N. West Street 302-655-2500 Wilmington, DE 19801 www.quakerhillhistoric.org To Learn about Harriett Tubman and Thomas Garrett, Lansdowne Friends Students Visit Quaker Hill by Ashley Cloud Quaker Hill echoed with the excited chatter of the Hicksite schism twenty 3rd and 4th graders from Lansdowne Friends over the Quaker School in Upper Darby, PA as they disembarked from community taking their bus on the corner of 4th and West early on Friday a proactive role in morning April 1st. This precocious bunch joined us as abolitionism. While part of the Underground Railroad field trip conceived the children and their by their teacher Alison Levie, to give her students a chaperones enjoyed visceral experience as they traced Harriet Tubman’s snacks and water, we story to her birthplace in Bucktown, Maryland. Given explored the relation- the school’s Quaker roots and its location near Thomas ship between Thomas Garret’s birthplace, a visit to Quaker Hill was a natural Garrett and Harriet starting point on their educational journey. Tubman in the con- The children had wonderful, inquisitive energy as text of the times and we began our presentation at the corner of 5th and their remarkable ac- West at the site of the first residence in Quaker Hill complishments in the built by Thomas West in 1738. The idea of history be- face of personal peril. ing a scavenger hunt for clues had them scouring the The attentive students had excellent remarks and building and pointing out the carvings and dates they questions. -

Street Name List

KENT COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING SERVICES Approved and Proposed Street Names MAPPING/911 ADDRESSING DIVISION 555 BAY ROAD, DOVER, DE 19901 THIS LIST IS FOR REFERENCE PURPOSES ONLY AND IS SUBJECT TO ph: 302-744-2420 f: 302-736-2128 PERIODIC CHANGES [email protected] Street Location Street Location Street Location Street Location ALBERTA MISTY PINES AMUR KESSELRING APPOORVA GARRISON LAKE GRE A ALBION ROESVILLE ESTATES - AMY ESTATES OF PICKERI APPRENTICE STEEPLECHASE AARON PAYNTERS VILLAGE ALBRIGHT GREEN MEADOWS ANCESTORS WALNUT SHADE RD 1 APRICOT DUCK CREEK TOWNH ABADON ABADON ESTATES ALCOTT JARRELL RIDGE ANCHOR BAY TREE APRIL WHITEOAK ROAD 240 ABAGAIL SOUTHFIELD ALDEN BUTTERFIELDS ANCHOR INN FREDRICK LODGE N/O AQUAMARINE EMERALD POINTE ABBEY WORTHINGTON ALDER MAYFAIR ANCRUM WEXFORD ARABIAN STEEPLECHASE ABBOTT MILFORD ALDERBROOK WORTHINGTON ANDALUSIAN THOROUGHBRED FAR ARBOR WESTFIELD ABBOTTS POND HOUSTON S/O ALEMBIC WEXFORD ANDARE OVATIONS ARDEN GATE WAY MEADOWS ABEC FELTON ALEXANDRIA WOODLAND MANOR ANDERSON MAGNOLIA W/O ARDMONT AUBURN MEADOWS ABEL STAR HILL VILLAGE ALEXIS CHESWOLD FARMS ANDIRON CHIMNEY HILL PHASE ARDMORE CENTERVILLE ABELIA WILLOWWOOD ALEZACH ESTATES OF VERONA ANDIRON CHIMNEY HILL SUBDIV ARDSLEY CARLISLE VILLAGE ABGAIL ESTATES OF PICKERI ALFALFA SUNNYSIDE VILLAGE ANDOVER BRANCH PROVIDENCE CROSSI ARIA WIND SONG FARMS ABODE HOMESTEAD ALFORD EDEN HILL FARM ANDRENA WELSH PROPERTY 9-0 ARIEL NOBLES POND 3 ABRUZZI OLD COUNTRY FARM ALGIERS GREEN SUBDIVISION ANDREW PRESIDENTS WAY ARISTOCRAT THE PONDS AT WILLO ACCESS ROBERT -

The Role of Historical Context in New Jersey V

The Role of Historical Context in New Jersey v. Delaware III (2008) Matthew F. Boyer, The Role of Historical Context in New Jersey v. Delaware III (2008), 11 DEL. L. REV. 101, 123 (2010). Copyright © 2010 by Delaware Law Review; Matthew F. Boyer. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission. Newark Office Wilmington Office 267 East Main Street 1000 West Street; Suite 1400 Newark, DE 19711 Wilmington, DE 19802 © 2017 Connolly Gallagher, LLP T 302-757-7300 F 302-757-7299 THE ROLE OF HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN NEW JERSEY v...., 11 Del. L. Rev. 101 11 Del. L. Rev. 101 Delaware Law Review 2010 Matthew F. Boyera1 Copyright © 2010 by Delaware Law Review; Matthew F. Boyer THE ROLE OF HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN NEW JERSEY v. DELAWARE III (2008) “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” --L. P. Hartley, from “The Go Between” The 2008 decision of the United States Supreme Court in New Jersey v. Delaware1 (“NJ v. DE III”) was hailed as a victory for Delaware, and so it was. The Court upheld Delaware’s authority to block the construction of a liquefied natural gas (“LNG”) unloading terminal that would have extended from New Jersey’s side of the Delaware River well into Delaware territory. But while the case involved modern concerns over the environment, clean energy, and even the threat of terrorist attack, the States’ underlying dispute was, like the River itself, of ancient origin, with a folklore of its own, and powerful, sometimes twisting currents. This was New Jersey’s third Supreme Court original jurisdiction action against Delaware since the Civil War, all challenging Delaware’s claim to sovereignty within a twelve-mile circle from the town of New Castle, which reaches across the River to within a few feet of the New Jersey side. -

Quaker Hill Quill

Quaker Hill Quill Quaker Hill Historic Preservation Foundation Vol. VI, Number 2, July, 2017 521 N. West Street 302-655-2500 Wilmington, DE 19801 www.quakerhillhistoric.org Pacem in Terris Speaker John Bonifaz Makes Case Against Citizens United Ruling and for a 28th Amendment to U.S. Constitution by Terence Maguire; photo by Tim Bayard He also pointed out that, because corporations can now be regarded as persons, some have even begun to resist John Bonifaz, Wilmington Friends School class of 1984, government investigations into possible wrong-doing by is a tireless and resourceful leader in the fight against the claiming the right against self-incrimination. Citizens influence of big money in politics. He spoke to a crowded United has also allowed, through “corporate citizenship,” room at Westminster Presbyterian Church on May 30, foreign influence on American politics. 2017, one of the special guest speakers for Delaware Pa- Bonifaz sees a proposed 28th amendment to the Consti- cem in Terris, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary as tution as an an organization. answer to the Born in Wilmington, John has spent his adult life in New seemingly England, leaving Friends early in 1983 to attend Brown unlimited University. After Brown, he graduated from Harvard Law influence of School and settled into the Boston area until about seven big money years ago, when he, his wife Lissa, and their daughter Mari- on American sol moved to Amherst, Mass. He is able to do a great deal politics. A of his work from homes, though he still travels extensively. great major- His topic that night was “We the People: The Movement ity of Ameri- to Reclaim our Democracy and Defend our Constitution.” cans favor He discussed the organization he recently co-founded, Free overturning Speech for People, one of the primary aims of which is to the Citizens overturn the 2010 Citizens United decision of the Supreme United deci- Court. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination New

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NP S NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: New Castle Court House Other Name/Site Number: New Castle Court House Museum; Old Courthouse; Old Colony and State House; Delaware Cultural Resource Survey Number NO 1290 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 211 Delaware Street Not for publication: City/Town: New Castle Vicinity:_ State: DE County: New Castle Code: 3 Zip Code: 19720 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): JL Public-Local:__ District: _ Public-State:_X. Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Non-contributing 1 0 buildings 0 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Find Your Freedom Sites & Events

Sites and Events Participating in “Find Your Freedom”Event Thursday, March 10, 2016 Delaware Historical Society (DHS) tours: Sterling Selections silver exhibit with emphasis on Thomas Garrett presentation silver and African American themes and Old Town Hall 12:00 noon-1:15 Tour the silver exhibit with DHS curator of objects Jennifer Potts, followed by a guided tour of Old Town Hall by DHS Wilmington campus education curator Rebecca Faye. RSVP required. Participants can reserve spaces by calling 302-655-7161 or emailing [email protected] NTF; HTURB Delaware History Museum, 504 N. Market Street, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Network to Freedom Markers Unveiling 12:00 noon The contrasts between slavery and freedom are especially poignant in Denton, Maryland, where several sites recently recognized by the Network to Freedom will have new markers unveiled. At the Caroline County Courthouse, several unsuccessful escape attempts ended with the participants in custody. In 1848, free African American Isaac Gibson was tried and convicted at the Caroline County Courthouse for enticing John Stokes to freedom. Ten years later, Irishman Hugh Hazlett was placed in the adjacent jail for helping a group of freedom seekers, before he was sent back to Cambridge where he was convicted of his crime. The story of Richard Potter, a young African American boy kidnapped into slavery, ended more happily as he was rescued and reunited with his parents. The site of the reunion, formerly a hotel, and now the town hall, has been recognized by the NTF, as well as the home that he lived in as an adult and wrote his memoirs. -

Constitutional Settlements and the Economies of Secondary Seaports

An Interest in Union: Constitutional Settlements and the Economies of Secondary Seaports Rick Demirjian Rutgers University-Camden Prepared for the Sixteenth Annual Conference of the Program in Early American Economy and Society Library Company of Philadelphia October 6-7, 2016 1 In their 1990 study of the economic and ideological concerns framing the drafting of the Constitution, Cathy Matson and Peter Onuf broke important new ground. Re-examining the forging and ratification of the Constitution through the lens of political economy, Matson and Onuf gave equal attention to political and economic questions that weighed upon the minds of delegates and policymakers from throughout the confederated republic. A Union of Interests illuminated the intensity of interstate jealousies and how the need to satiate the developmental goals of tenacious local interests characterized constitutional formation. According to these two scholars, one important aspect of this process was how “the critical contribution of development rhetoric, even when aimed at promoting the interests of one city or region at the expense of others, [became] an expansive and dynamic conception of the American economy.” The sustained, successful employment of this rhetoric yielded a new nation characterized by the pursuit of self-interest in disinterested republican ways. This new union of interests demonstrated to increasing numbers of citizens that it could foster the development of political economies, “even as it transcended the specific local contexts in which ‘interest’ was often defined.”1 A developmentalist language steeped in shared republican assumptions about the ways in which elected leaders and economically powerful men (often one and the same) should direct policy for the greatest public good made it rhetorically possible, at times, to make national and local interests indistinct.