The Role of Historical Context in New Jersey V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Historic Landmark Nomination New

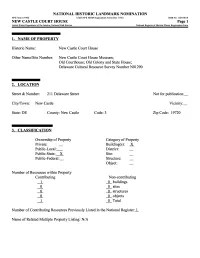

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: New Castle Court House Other Name/Site Number: New Castle Court House Museum; Old Courthouse; Old Colony and State House; Delaware Cultural Resource Survey Number NO 1290 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 211 Delaware Street Not for publication: City/Town: New Castle Vicinity:_ State: DE County: New Castle Code: 3 Zip Code: 19720 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): JL Public-Local:__ District: _ Public-State:_X. Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Non-contributing 1 0 buildings 0 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NEW CASTLE COURT HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, N ational Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

State of New Jersey, Petition for Review (PDF)

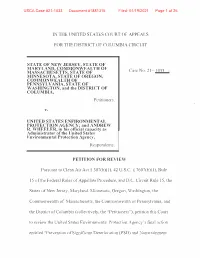

USCA Case #21-1033 Document #1881315 Filed: 01/19/2021 Page 1 of 26 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT STATE OF NEW JERSEY, STATE OF MARYLAND, COMMONWEAL TH OF MASSACHUSETTS, STATE OF Case No. 21 1033 MINNESOTA, STATE OF OREGON, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, STATE OF WASHINGTON, and the DISTRICT O_F COLUMBIA, Petitioners, v. UNITED STATES ENFIRONMENT AL PROTECTION AGENCY; and ANDREW R. WHEELER, in his official capacity as Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Respondents. PETITION FOR REVIEW Pursuant to Clean Air Act§ 307(b)(l), 42 U.S.C. § 7607(6)(1), Rule 15 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, and D.C. Circuit Rule 15, the States of New Jersey, Maryland, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia (collectively, the "Petitioners"), petition this Cou11 to review the United States Environmental Protection Agency's finalaction entitled "Prevention of Significant Deterioration(PSD) and Nonattainment USCA Case #21-1033 Document #1881315 Filed: 01/19/2021 Page 2 of 26 New Source Review (NNSR): Project Emissions Accounting," published at 85 Fed. Reg. 74,890 (Nov. 24, 2020). A copy of the rule is attached hereto as Attachment A. Dated: January 19, 2021 Respectfully Submitted, FOR THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY GURBIR GREWAL ATTORNEY GENERAL /s/Lisa J. Morelli LISA 1. MORELLI DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL NEW JERSEY DIVISION OF LAW 2S MARKET STREET TRENTON, NEW JERSEY 08625 Tel: (609) 376-2745 Email: Lisa.Morelli(a~l~ aw.n~oa .~ov CD UNSEL FOR THE STATE OF NEW MERSEY FOR THE STATE OF MARYLAND FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS BRIAN E. -

New Jersey State Department of Education Mercer County Office

2020-2021 NEW JERSEY STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MERCER COUNTY OFFICE CHARTER AND PUBLIC SCHOOLS DIRECTORY COUNTY OF MERCER McDade Administration Building 640 South Broad Street P.O. Box 8068 Trenton, New Jersey 08650 Brian M. Hughes, County Executive BOARD OF CHOSEN FREEHOLDERS John D. Cimino [email protected] Lucylle R. S. Walter [email protected] Ann M. Cannon [email protected] Samuel T. Frisby [email protected] Pasquale “Pat” Colavita [email protected] Nina Melker [email protected] Andrew Koontz [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS County Office of Education New Jersey Department of Education 1 State Board of Education 2 Mercer County Bd. of Chosen Freeholders 2 Mercer County Colleges and Universities 3 Mercer County Organizations 4 New Jersey Organizations 5 5 CHARTER SCHOOLS Achievers Early College Prep Charter 6 Foundation Academy Charter School 7 International Charter School 8 Pace Charter School of Hamilton 9 Paul Robeson Charter School for the Humanities 10 Princeton Charter School 11 StemCivics Charter School 12 Village Charter School 13 SCHOOL DISTRICTS East Windsor Regional 14 Ewing Township 15 Hamilton Township 16 -17 Hopewell Valley Regional 18 Lawrence Township 19 Marie Katzenbach School for the Deaf 20 Mercer County Special Services 21 Mercer County Technical 22 Princeton 23 Robbinsville 24 Trenton 25-26 West Windsor-Plainsboro Regional 27 SCHOOL DISTRICT CONTACTS: Affirmative Action Officers 28 NCLB Contacts 28 Bilingual/ESL Contacts 29 Coordinators of School Improvement -

New Jersey SAFE Act

New Jersey SAFE Act The New Jersey Security and Financial Empowerment Act (“NJ SAFE Act”), P.L. 2013, c.82, provides that certain employees are eligible to receive an unpaid leave of absence, for a period not to exceed 20 days in a 12-month period, to address circumstances resulting from domestic violence or a sexually violent offense. To be eligible, the employee must have worked at least 1,000 hours during the immediately preceding 12-month period. Further, the employee must have worked for an employer in the State that employs 25 or more employees for each working day during each of 20 or more calendar workweeks in the then-current or immediately preceding calendar year. Leave under the NJ SAFE Act may be taken by an employee who is a victim of domestic violence, as that term is defined in N.J.S.A. 2C:25-19, or a victim of a sexually violent offense, as that term is defined in N.J.S.A. 30:4-27.6. Leave may also be taken by an employee whose child, parent, spouse, domestic partner, or civil union partner is a victim of domestic violence or a sexually violent offense. Leave under the NJ SAFE Act may be taken for the purpose of engaging in any of the following activities as they relate to an incident of domestic violence or a sexually violent offense: (1) Seeking medical attention for, or recovering from, physical or psychological injuries caused by domestic or sexual violence to the employee or the employee’s child, parent, spouse, domestic partner or civil union partner (2) Obtaining services from a victim services organization for -

New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-CT Nonattainment Area

New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-CT Nonattainment Area Final Area Designations for the 2015 Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards Technical Support Document (TSD) 1.0 Summary This technical support document (TSD) describes the EPA’s final designation for the counties of Fairfield, New Haven and Middlesex in the state of Connecticut; the counties of Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Hunterdon, Middlesex, Monmouth, Morris, Passaic, Somerset, Sussex, Union and Warren in the state of New Jersey; and the counties of Bronx, Kings, Nassau, New York, Queens, Richmond, Rockland, Suffolk and Westchester in the state of New York as nonattainment, and include them in a single nonattainment area, for the 2015 ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). We refer to this nonattainment area as the New York- Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-CT Nonattainment Area, also referred to as the New York Metro nonattainment Area. On October 1, 2015, the EPA promulgated revised primary and secondary ozone NAAQS (80 FR 65292; October 26, 2015). The EPA strengthened both standards to a level of 0.070 parts per million (ppm). In accordance with Section 107(d) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), whenever the EPA establishes a new or revised NAAQS, the EPA must promulgate designations for all areas of the country for that NAAQS. Under section 107(d), states were required to submit area designation recommendations to the EPA for the 2015 ozone NAAQS no later than 1 year following promulgation of the standards, i.e., by October 1, 2016. Tribes were also invited to submit area designation recommendations. -

Delaware County: Community Health Assessment and Improvement Plan and Community Service Plans

2016- 2018 Delaware County: Community Health Needs Assessment and Improvement Plan and Community Service Plans This page was intentionally left blank. 1 | P a g e Delaware County 2016-2018 Community Health Needs Assessment and Improvement Plan and Community Service Plans Local Health Department: Delaware County Public Health Amanda Walsh, MPH, Public Health Director 99 Main Street, Delhi, NY 13856 607-832-5200 [email protected] Heather Warner, Health Education Coordinator 99 Main Street, Delhi, NY 13856 607-832-5200 [email protected] Hospitals: UHS Delaware Valley Hospital Dotti Kruppo, Community Relations Director 1 Titus Place Walton, NY 13856 607-865-2409 [email protected] Margaretville Hospital Laurie Mozian, Community Health Coordinator 42084 NY Route 28, Margaretville, NY 12455 845-338-2500 [email protected] Mark Pohar, Executive Director 42084 NY Route 28, Margaretville, NY 12455 845-586-2631 [email protected] O’Connor Hospital Amy Beveridge, Director of Operational Support 460 Andes Road, Delhi, NY 13753 607-746-0331 [email protected] Tri-Town Regional Hospital Amy Beveridge, Director of Operational Support 43 Pearl Street W., Sidney, NY 13838 607-746-0331 [email protected] Community Health Assessment update completed with the assistance of the HealthlinkNY Community Network, the regional Population Health Improvement Program (PHIP) in the Southern Tier. Support provided by Emily Hotchkiss and Mary Maruscak. 2 | P a g e 2016-2018 Community Health Needs Assessment and Improvement Plan for Delaware County Table of Contents Executive Summary 4-7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction 8-9 Mission 8 Vision 8 Core Values 8 Background and Purpose 9 Community Health Assessment Update 9-82 I. -

Preparing for Tomorrow's High Tide

Preparing for Tomorrow’s High Tide Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment for the State of Delaware July 2012 Other Documents in the Preparing for Tomorrow’s High Tide Series A Progress Report of the Delaware Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee (November 2011) A Mapping Appendix to the Delaware Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment (July 2012) Preparing for Tomorrow’s High Tide Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment for the State of Delaware Prepared for the Delaware Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee by the Delaware Coastal Programs of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control i About This Document This Vulnerability Assessment was developed by members of Delaware’s Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee and by staff of the Delaware Coastal Programs section of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. It contains background information about sea level rise, methods used to determine vulnerability and a comprehensive accounting of the extent and impacts that sea level rise will have on 79 resources in the state. The information contained within this document and its appendices will be used by the Delaware Sea Level Rise Advisory Committee and other stakeholders to guide development of sea level rise adaptation strategies. Users of this document should carefully read the introductory materials and methods to understand the assumptions and trade-offs that have been made in order to describe and depict vulnerability information at a statewide scale. The Delaware Coastal Programs makes no warranty and promotes no other use of this document other than as a preliminary planning tool. This project was funded by the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, in part, through a grant from the Delaware Coastal Programs with funding from the Offi ce of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrations, under award number NA11NOS4190109. -

The Delawarean (Dover, Del.), 1900-09-29

/ ■ ? I ■ X 2 TILE DELAWAREAN, DOVER, DELAWARE, SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 190(f m ---------- - __ THE DELAWAREAN, eemtatton -of the Issues at stake in the ten beef?” asked tone of 'the auditor*. State's Vi tmpaign and will be read with 41 ate lit,” responded' Roosevelt, “but - Established 1859. 1 interest! A man .possessing the senltl- you will never get 'near enough Ito be mente expressed by Mir. Ford le a safe Mt with a bullet, (or within five miles WILLIAM SAULSBDRT, Ease your burdens man to iti with executive powers. of it.” This was an' ilntimatlon that Edito* and Profeiktor. This is li'kfely to 'be the opinion of the inlterrogatior was a «xxwiard. Mr. 8Mm m Sou * b State Street, Oppeelte Court Houle. every thinking voter -wiho reads this Roosevelt 'is given to classing people by USING Telephone, No. 36. speech. who do raolt agree with, him as cowards. The 1tenderfoot of ithe Basil tolerate it The Delawarean is published each Satur ier and Wednesday Subscription prioe, $1.00 «DROPPING THE MASK. as they know Teddy, but to the per annum, strictly in adTanoe- Advertising rates In a speech dielivenad at Chicago denizens of the wild end wooly west tarnished on application. GOLD Correspondence solicited, but it must al recently, Hon. David B. Hendrason, (the epithet is regarded as a deadly in- ss ways be accompanied by the narno of the writer, Speaker of the House of Represenlaa- JsullO. lit brought trouble i.lo Teddy. not for publication, but for our information. Tho V W V proprietor disclaims all responsibility for the opin . -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Key Findings: Existing Conditions Report – January 2017

NY 443/Delaware Avenue from Elsmere Avenue to the Normanskill Bridge Summary of Key Findings: Existing Conditions Report – January 2017 NY 443/Delaware Avenue in the Town of Bethlehem is owned and maintained by New York State. In general, it is a four-lane roadway 48 feet wide, with two 11-foot wide travel lanes in each direction, one-foot wide shoulders, and two-foot wide striping in the center. The roadway widens in the central part of the study area near Delaware Plaza and provides a 5-lane cross section (60 feet wide), and transitions on both ends to provide a two-lane cross section entering the Delmar hamlet on the west, and the City of Albany to the east. The roadway right-of-way is typically 66 feet wide; 90 feet wide near the Delaware Plaza, and variable width approaching the Normanskill bridge. As an urban minor arterial in a Commercial Hamlet District, Delaware Avenue serves several different functions. The roadway provides access to adjacent residential neighborhood streets and residences, businesses and a school, as well as serving as a multi-modal commuting route between the Town of Bethlehem and the City of Albany and activities elsewhere in the region. Delaware Avenue from Elsmere Avenue to Delaware Plaza carries about 18,300 vehicles on an average weekday. Daily traffic volumes between Delaware Plaza and the Normanskill Bridge are lower at approximately 15,600 vehicles. The amount of motor vehicle traffic along Delaware Avenue has remained relatively the same over the last 30 years. CDTA’s bus route 18 travels the study area providing service between Slingerlands and downtown Albany with most frequent service provided during the evening commute. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy.