The Development of Molecular Biology and the Discovery of the Structure Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insight from the Sociology of Science

CHAPTER 7 INSIGHT FROM THE SOCIOLOGY OF SCIENCE Science is What Scientists Do It has been argued a number of times in previous chapters that empirical adequacy is insufficient, in itself, to establish the validity of a theory: consistency with the observable ‘facts’ does not mean that a theory is true,1 only that it might be true, along with other theories that may also correspond with the observational data. Moreover, empirical inadequacy (theories unable to account for all the ‘facts’ in their domain) is frequently ignored by individual scientists in their fight to establish a new theory or retain an existing one. It has also been argued that because experi- ments are conceived and conducted within a particular theoretical, procedural and instrumental framework, they cannot furnish the theory-free data needed to make empirically-based judgements about the superiority of one theory over another. What counts as relevant evidence is, in part, determined by the theoretical framework the evidence is intended to test. It follows that the rationality of science is rather different from the account we usually provide for students in school. Experiment and observation are not as decisive as we claim. Additional factors that may play a part in theory acceptance include the following: intuition, aesthetic considerations, similarity and consistency among theories, intellectual fashion, social and economic influences, status of the proposer(s), personal motives and opportunism. Although the evidence may be inconclusive, scientists’ intuitive feelings about the plausibility or aptness of particular ideas will make it appear convincing. The history of science includes many accounts of scientists ‘sticking to their guns’ concerning a well-loved theory in the teeth of evidence to the contrary, and some- times in the absence of any evidence at all. -

The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021

More Fun Than Fun: The Joys and Burdens of Our Heroes 12/05/2021 An iconic photo of Konrad Lorenz with his favourite geese. Photo: Willamette Biology, CC BY-SA 2.0 This article is part of the ‘More Fun Than Fun‘ column by Prof Raghavendra Gadagkar. He will explore interesting research papers or books and, while placing them in context, make them accessible to a wide readership. RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR Among the books I read as a teenager, two completely changed my life. One was The Double Helix by Nobel laureate James D. Watson. This book was inspiring at many levels and instantly got me addicted to molecular biology. The other was King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz, soon to be a Nobel laureate. The study of animal behaviour so charmingly and unforgettably described by Lorenz kindled in me an eternal love for the subject. The circumstances in which I read these two books are etched in my mind and may have partly contributed to my enthusiasm for them and their subjects. The Double Helix was first published in London in 1968 when I was a pre-university student (equivalent to 11th grade) at St Joseph’s college in Bangalore and was planning to apply for the prestigious National Science Talent Search Scholarship. By then, I had heard of the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA and its profound implications. I was also tickled that this momentous discovery was made in 1953, the year of my birth. I saw the announcement of Watson’s book on the notice board in the British Council Library, one of my frequent haunts. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

Barbara Mcclintock's World

Barbara McClintock’s World Timeline adapted from Dolan DNA Learning Center exhibition 1902-1908 Barbara McClintock is born in Hartford, Connecticut, the third of four children of Sarah and Thomas Henry McClintock, a physician. She spends periods of her childhood in Massachusetts with her paternal aunt and uncle. Barbara at about age five. This prim and proper picture betrays the fact that she was, in fact, a self-reliant tomboy. Barbara’s individualism and self-sufficiency was apparent even in infancy. When Barbara was four months old, her parents changed her birth name, Eleanor, which they considered too delicate and feminine for such a rugged child. In grade school, Barbara persuaded her mother to have matching bloomers (shorts) made for her dresses – so she could more easily join her brother Tom in tree climbing, baseball, volleyball, My father tells me that at the and football. age of five I asked for a set of tools. He My mother used to did not get me the tools that you get for an adult; he put a pillow on the floor and give got me tools that would fit in my hands, and I didn’t me one toy and just leave me there. think they were adequate. Though I didn’t want to tell She said I didn’t cry, didn’t call for him that, they were not the tools I wanted. I wanted anything. real tools not tools for children. 1908-1918 McClintock’s family moves to Brooklyn in 1908, where she attends elementary and secondary school. In 1918, she graduates one semester early from Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. -

I. Hox Genes 2

School ofMedicine Oregon Health Sciences University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL This is certify that the Ph.D. thesis of WendyKnosp has been approved Mentor/ Advisor ~ Member Member QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF HOXA13 FUNCTION IN THE DEVELOPING LIMB By Wendy M. lt<nosp A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics and the Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS X ABSTRACT xii CHAPTER 1: Introduction 1 I. Hox genes 2 A. Discovery of Hox genes in Drosophila melanogaster 2 B. Hox cluster colinearity and conservation 7 C. Human Hox mutations 9 D. Hoxa13: HFGS and Guttmacher syndromes 10 II. The Homeodomain 12 A. Homeodomain structure 12 B. DNA binding 14 Ill. Limb development 16 A. Patterning of the limb axes 16 B. Digit formation 20 C. lnterdigital programmed cell death 21 IV. BMPs and limb development 23 A. BMP signaling in the limb 23 B. BMP target genes 27 V. Hoxa13 and embryonic development 30 A. The Hoxa13-GFP mouse model 30 B. Hoxa13 mutant phenotypes 34 C. HOXA 13 homeodomain 35 D. HOXA 13 protein-protein interactions 36 E. HOXA 13 target genes 37 VI. Hypothesis and Rationale 39 CHAPTER 2: HOXA13 regulates Bmp2 and Bmp7 40 I. Abstract 42 II. Introduction 43 Ill. Results 46 IV. Discussion 69 v. Materials and Methods 75 VI. Acknowledgements 83 11 CHAPTER 3: Quantitative analysis of HOXA13 function 84 HOXA 13 regulation of Sostdc1 I. -

The Contributions of George Beadle and Edward Tatum

| PERSPECTIVES Biochemical Genetics and Molecular Biology: The Contributions of George Beadle and Edward Tatum Bernard S. Strauss1 Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637 KEYWORDS George Beadle; Edward Tatum; Boris Ephrussi; gene action; history It will concern us particularly to take note of those cases in Genetics in the Early 1940s which men not only solved a problem but had to alter their mentality in the process, or at least discovered afterwards By the end of the 1930s, geneticists had developed a sophis- that the solution involved a change in their mental approach ticated, self-contained science. In particular, they were able (Butterfield 1962). to predict the patterns of inheritance of a variety of charac- teristics, most morphological in nature, in a variety of or- EVENTY-FIVE years ago, George Beadle and Edward ganisms although the favorites at the time were clearly Tatum published their method for producing nutritional S Drosophila andcorn(Zea mays). These characteristics were mutants in Neurospora crassa. Their study signaled the start of determined by mysterious entities known as “genes,” known a new era in experimental biology, but its significance is to be located at particular positions on the chromosomes. generally misunderstood today. The importance of the work Furthermore, a variety of peculiar patterns of inheritance is usually summarized as providing support for the “one gene– could be accounted for by alteration in chromosome struc- one enzyme” hypothesis, but its major value actually lay both ture and number with predictions as to inheritance pattern in providing a general methodology for the investigation of being quantitative and statistical. -

Watson's Way with Words

books and arts My teeth were set on edge by reference to “the stable form of uranium”,a violation of Kepler’s second law in a description of how the Earth’s orbit would change under various circumstances, and by “the rest mass of the neutrino is 4 eV”. Collins has been well served by his editor and publisher, but not perfectly. There are un-sort-out-able mismatches between text and index, references and figures; acronyms D.WRITING LIFE OF JAMES THE WATSON in the second half of the alphabet go un- decoded; several well-known names are misspelled. And readers are informed that Weber’s death occurred “on September 31, E. C. FRIEDBERG, 2000”. Well, Joe always said he could do things that other people couldn’t, but there are limits. Incidentally, my adviser was partly right: I should not have agreed to review this book. It is very much harder to hear harsh, some- times false, things said about one’s spouse after he can no longer defend himself. I am not alone in this feeling. Carvel Gold, widow of Thomas Gold, whose work was also far from universally accepted (see Nature 430, 415;2004),says the same thing. ■ Virginia Trimble is at the University of California, Irvine, California 92697-4575, USA. She and Joe The write idea? In The Double Helix,James Watson gave Weber were married from 16 March 1972 until his a personal account of the quest for the structure of DNA. death on 30 September 2000. Watson set out to produce a good story that the public would enjoy as much as The Great Gatsby.He started writing in 1962 with the working title “Honest Jim”,which is illumi- Watson’s way nating in itself. -

Genes, Genomes and Genetic Analysis

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION UNIT 1 © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORDefining SALE OR DISTRIBUTION and WorkingNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION with Genes © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Chapter 1 Genes, Genomes, and Genetic Analysis Chapter 2 DNA Structure and Genetic Variation © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Molekuul/Science Photo Library/Getty Images. © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 9781284136609_CH01_Hartl.indd 1 08/11/17 8:50 am © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC -

Barbara Mcclintock

Barbara McClintock Lee B. Kass and Paul Chomet Abstract Barbara McClintock, pioneering plant geneticist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983, is best known for her discovery of transposable genetic elements in corn. This chapter provides an overview of many of her key findings, some of which have been outlined and described elsewhere. We also provide a new look at McClintock’s early contributions, based on our readings of her primary publications and documents found in archives. We expect the reader will gain insight and appreciation for Barbara McClintock’s unique perspective, elegant experiments and unprecedented scientific achievements. 1 Introduction This chapter is focused on the scientific contributions of Barbara McClintock, pioneering plant geneticist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983 for her discovery of transposable genetic elements in corn. Her enlightening experiments and discoveries have been outlined and described in a number of papers and books, so it is not the aim of this report to detail each step in her scientific career and personal life but rather highlight many of her key findings, then refer the reader to the original reports and more detailed reviews. We hope the reader will gain insight and appreciation for Barbara McClintock’s unique perspective, elegant experiments and unprecedented scientific achievements. Barbara McClintock (1902–1992) was born in Hartford Connecticut and raised in Brooklyn, New York (Keller 1983). She received her undergraduate and graduate education at the New York State College of Agriculture at Cornell University. In 1923, McClintock was awarded the B.S. -

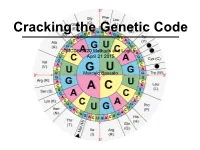

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J.