Larger Than Tigers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary, Cardamom Mountains, Southwest Cambodia

Zootaxa 3388: 41–55 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of kukri snake (Colubridae: Oligodon Fitzinger, 1826) from the Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary, Cardamom Mountains, southwest Cambodia THY NEANG1,2, L. LEE GRISMER3 & JENNIFER C. DALTRY4 1Department of National Parks, Ministry of Environment, # 48, Samdech Preah Sihanouk, Tonle Bassac, Chamkarmorn, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 2Fauna & Flora International (FFI), Cambodia. # 19, Street 360, BKK1, Chamkarmorn, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Biology, La Sierra University, 4500 Riverwalk Parkway, Riverside, California, 92515-8247 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4Fauna & Flora International (FFI), Jupiter House (4th Floor), Station Road, Cambridge, CB1 2JD, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of kukri snake Oligodon Fitzinger, 1826 is described from the Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary, Carda- mom Mountains, southwest Cambodia. Oligodon kampucheaensis sp. nov. differs from other Indochinese and Southeast Asian species of Oligodon by having 15–15–15 dorsal scale rows; 164 ventral scales; 39 subcaudal scales; anal plate un- divided; deep bifurcated hemipenes, lacking papillae and spines extending to subcaudal scale 11; 17 transverse cream and black-edged bands on body; three bands on tail; eight or nine scales long between dorsal bands; white ventrolateral spots on the lateral margin of every dark brown squarish or subrectangular ventral blotch. The hemipenial characters place it as the tenth species of the O. cyclurus group but it has a lower dorsal scale count than other species in this group. -

Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop Reflections by Brian Sheppard 11

WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Tongariro National Park, New Zealand 26–30 October 2000 Contents/Introduction 1 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP Cover: Ngatoroirangi, a tohunga and navigator of the Arawa canoe, depicted rising from the crater to tower over the three sacred mountains of Tongariro National Park—Tongariro (foreground), Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu (background). Photo montage: Department of Conservation, Turangi This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington; design and layout by Ian Mackenzie. © Copyright October 2001, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–22125–8 Published by: DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit Science and Technical Centre Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Search our catalogue at http://www.doc.govt.nz 2 World Heritage Managers Workshop—Tongariro, 26–30 October 2000 WORLD HERITAGE MANAGERS WORKSHOP CONTENTS He Kupu Whakataki—Foreword by Tumu Te Heuheu 7 Hemi Kingi by Brian Sheppard 9 Workshop reflections by Brian Sheppard 11 EVALUATING WORLD HERITAGE MANAGEMENT 13 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Performance management and evaluation 15 Terry Bailey, Projects Manager, Kakadu National Park, NT, Australia Managing our World Heritage 25 Hugh Logan, Director General, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand Tracking the fate of New Zealand’s natural -

Quarterly Progress Report January-March 2020

KARNATAKA NEERAVARI NIGAM LTD Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program ADB LOAN 3836-IND Quarterly Progress Report January-March 2020 Project Management Unit, KISWRMIP Project Support Consultant SMEC International Pty. Ltd. Australia in association with SMEC (India) Pvt. Ltd. 3 June 2020 Revised 20 June 2020 DOCUMENTS/REPORT CONTROL FORM Report Name Quarterly Progress Report January-March 2020 (draft) Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Project Name: Investment Program Project Number: 5061164 Report for: Karnataka Neeravari Nigam Ltd (KNNL) REVISION HISTORY Revision Date Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by # Dr. Srinivas Mudrakartha Dr Srinivas Dr Srinivas 1 3 June 2020 Mudrakartha/ Mudrakartha/ Balaji Maddikera Gaurav Srivastava Gaurav Srivastava Deepak GN and Team Dr. Srinivas Mudrakartha Dr Srinivas Dr Srinivas Mudrakartha/ Mudrakartha/ 2 20 June 2020 Balaji Maddikera Gaurav Srivastava Gaurav Srivastava Deepak GN and Team ISSUE REGISTER Distribution List Date Issued Number of Copies KNNL 20 June 2020 10 SMEC Staff 20 June 2020 2 Associate (Gaurav Srivastava) 20 June 2020 1 Office Library (Shimoga) 20 June 2020 1 SMEC Project File 20 June 2020 2 SMEC COMPANY DETAILS Dr Janardhan Sundaram, Executive Director 1st Floor, Novus Tower, West Wing, Plot Number -18, Sector – 18, Gurgaon – 122016, Haryana Tel: +91 124 4501100 Fax: +91 124 4376018 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.smec.com CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4 -

Hanna Rosti. Conservation News

Conservation news 153 SIMON BEARDER Nocturnal Primates Research Group, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK JAMES MWANG’OMBE MWAMODENYI Kenya Forest Service, Kenya *Also at: Taita Research Station, Wundanyi, Kenya Privately funded land purchase programme in Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, India The Taita Mountain dwarf galago Paragalago sp. photographed Habitat fragmentation and loss are the most serious threats to in Ngangao Forest in . Photo: Hanna Rosti. biodiversity and ecological integrity. In this context, privately held land enclaves within the biologically rich Western of which was successful. We regularly observed dwarf galagos Ghats of India have negative impacts on biodiversity, includ- hunting insects on small trees with a trunk diameter of – cm. ing within protected areas. These impacts include persecution We also observed galagos both descending to the ground and of wildlife arising from negative human–wildlife interactions, ascending to the forest canopy at c. m. In the morning and overgrazing, firewood collection and illegal hunting. group members made loud incremental calls close to their To address this issue, the Wildlife Conservation Society– nest site. The Ngangao group used several tree hollows as India is using an innovative habitat consolidation project daytime sleeping sites, moving every few days. We heard to facilitate the voluntary relinquishment of such privately and recorded incremental contact calls irregularly throughout owned land to the state government, for the specific purpose the night. Because of the small size of this population, and pre- of amalgamating such land with adjacent protected areas. dation pressure, its future in Ngangao Forest is bleak. In the The compensation to the land owner is paid directly by Wild- larger Mbololo Forest we heard dwarf galagos throughout life Conservation Society–India (WCS–India) on mutually the fragment, although they were shy and our visual observa- agreed terms. -

5- Informe ASEAN- Centre-1.Pdf

ASEAN at the Centre An ASEAN for All Spotlight on • ASEAN Youth Camp • ASEAN Day 2005 • The ASEAN Charter • Visit ASEAN Pass • ASEAN Heritage Parks Global Partnerships ASEAN Youth Camp hen dancer Anucha Sumaman, 24, set foot in Brunei Darussalam for the 2006 ASEAN Youth Camp (AYC) in January 2006, his total of ASEAN countries visited rose to an impressive seven. But he was an W exception. Many of his fellow camp-mates had only averaged two. For some, like writer Ha Ngoc Anh, 23, and sculptor Su Su Hlaing, 19, the AYC marked their first visit to another ASEAN country. Since 2000, the AYC has given young persons a chance to build friendships and have first hand experiences in another ASEAN country. A project of the ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, the AYC aims to build a stronger regional identity among ASEAN’s youth, focusing on the arts to raise awareness of Southeast Asia’s history and heritage. So for twelve days in January, fifty young persons came together to learn, discuss and dabble in artistic collaborations. The theme of the 2006 AYC, “ADHESION: Water and the Arts”, was chosen to reflect the role of the sea and waterways in shaping the civilisations and cultures in ASEAN. Learning and bonding continued over visits to places like Kampung Air. Post-camp, most participants wanted ASEAN to provide more opportunities for young people to interact and get to know more about ASEAN and one another. As visual artist Willy Himawan, 23, put it, “there are many talented young people who could not join the camp but have great ideas Youthful Observations on ASEAN to help ASEAN fulfill its aims.” “ASEAN countries cooperate well.” Sharlene Teo, 18, writer With 60 percent of ASEAN’s population under the age of thirty, young people will play a critical role in ASEAN’s community-building efforts. -

Change Notification No 06 2015

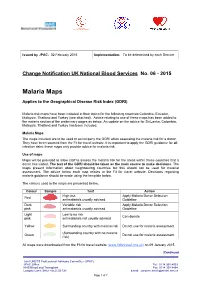

Northern Ireland BLOOD TRANSFUSION SERVICE Issued by JPAC: 02 February 2015 Implementation: To be determined by each Service Change Notification UK National Blood Services No. 06 - 2015 Malaria Maps Applies to the Geographical Disease Risk Index (GDRI) Malaria risk maps have been included in their topics for the following countries Colombia, Ecuador, Malaysia, Thailand and Turkey (see attached). Advice relating to use of these maps has been added to the malaria section of the preliminary pages as below. An update on the advice for Sri Lanka, Colombia, Malaysia, Thailand,and Turkey has been included. Malaria Maps The maps included are to be used to accompany the GDRI when assessing the malaria risk for a donor. They have been sourced from the Fit for travel website. It is important to apply the GDRI guidance for all infection risks; these maps only provide advice for malaria risk. Use of maps Maps will be provided to allow staff to assess the malaria risk for the areas within these countries that a donor has visited. The text of the GDRI should be taken as the main source to make decisions. The maps present information about neighbouring countries but this should not be used for malarial assessment. The advice below each map relates to the Fit for travel website. Decisions regarding malaria guidance should be made using the template below. The colours used in the maps are presented below. Colour Sample Text Action High risk Apply Malaria Donor Selection Red antimalarials usually advised Guideline Dark Variable risk Apply Malaria Donor -

Asian Ibas & Ramsar Sites Cover

■ INDIA RAMSAR CONVENTION CAME INTO FORCE 1982 RAMSAR DESIGNATION IS: NUMBER OF RAMSAR SITES DESIGNATED (at 31 August 2005) 19 Complete in 11 IBAs AREA OF RAMSAR SITES DESIGNATED (at 31 August 2005) 648,507 ha Partial in 5 IBAs ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORITY FOR RAMSAR CONVENTION Special Secretary, Lacking in 159 IBAs Conservation Division, Ministry of Environment and Forests India is a large, biologically diverse and densely populated pressures on wetlands from human usage, India has had some country. The wetlands on the Indo-Gangetic plains in the north major success stories in wetland conservation; for example, of the country support huge numbers of breeding and wintering Nalabana Bird Sanctuary (Chilika Lake) (IBA 312) was listed waterbirds, including high proportions of the global populations on the Montreux Record in 1993 due to sedimentation problem, of the threatened Pallas’s Fish-eagle Haliaeetus leucoryphus, Sarus but following successful rehabilitation it was removed from the Crane Grus antigone and Indian Skimmer Rynchops albicollis. Record and received the Ramsar Wetland Conservation Award The Assam plains in north-east India retain many extensive in 2002. wetlands (and associated grasslands and forests) with large Nineteen Ramsar Sites have been designated in India, of which populations of many wetland-dependent bird species; this part 16 overlap with IBAs, and an additional 159 potential Ramsar of India is the global stronghold of the threatened Greater Sites have been identified in the country. Designated and potential Adjutant Leptoptilos dubius, and supports important populations Ramsar Sites are particularly concentrated in the following major of the threatened Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis, Lesser wetland regions: in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, two designated Adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus, White-winged Duck Cairina Ramsar Sites overlap with IBAs and there are six potential scutulata and wintering Baer’s Pochard Aythya baeri. -

WESTERN GHATS HOME to 3,387 LEOPARDS Relevant For: Environment | Topic: Biodiversity, Ecology, and Wildlife Related Issues

Source : www.thehindu.com Date : 2020-12-23 WESTERN GHATS HOME TO 3,387 LEOPARDS Relevant for: Environment | Topic: Biodiversity, Ecology, and Wildlife Related Issues Cat count:India has an estimated population of 12,852 leopards.M.A. SRIRAM The Western Ghats region is home to 3,387 leopards stealthily roaming around its forests. Karnataka tops the list with 1,783 leopards, followed by Tamil Nadu with 868, according to the Status of Leopards in India 2018 report. With 650 leopards, Kerala has the third highest number of big cats in the Western Ghats region. Goa has 86. “The Western Ghats is home to 3,387 leopards, against India’s population of 12,852,” says the report released recently by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. The leopard population was counted during the tiger population assessment undertaken in 2018. The leopard population was estimated to be within the forested habitats in tiger-occupied States, the report said. The presence of the animal was recorded in the forested areas of Western Ghats, Nilgiris, and sporadically across much of the dry forests of Central Karnataka. Leopard population of the Western Ghats landscape was reported from the four distinct blocks. The Northern block covered the contiguous forests of Radhanagari and Goa covering Haliyal- Kali Tiger Reserve, Karwar, Honnavar, Madikeri, Kudremukh, Shettihali Wild Life Sanctuary (WLS), Bhadra and Chikmagalur. The Central population covered southern Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and northern Kerala covering the forests of Virajpet, Nagarhole, Bandipur, Madumalai, Satyamangalam, Nilgiris, Silent Valley, Wayanad, BRT Hills, MM Hills, Cauvery WLS, Bannerghhata National Park. -

Lorentz National Park Indonesia

LORENTZ NATIONAL PARK INDONESIA Lorentz National Park is the largest protected area in southeast Asia and one of the world’s last great wildernesses. It is the only tropical protected area to incorporate a continuous transect from snowcap to sea, and include wide lowland wetlands. The mountains result from the collision of two continental plates and have a complex geology with glacially sculpted peaks. The lowland is continually being extended by shoreline accretion. The site has the highest biodiversity in New Guinea and a high level of endemism. Threats to the site: road building, associated with forest die-back in the highlands, and increased logging and poaching in the lowlands. COUNTRY Indonesia NAME Lorentz National Park NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1999: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE [pending] The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription: Justification for Inscription The site is the largest protected area in Southeast Asia (2.35 mil. ha.) and the only protected area in the world which incorporates a continuous, intact transect from snow cap to tropical marine environment, including extensive lowland wetlands. Located at the meeting point of two colliding continental plates, the area has a complex geology with on-going mountain formation as well as major sculpting by glaciation and shoreline accretion which has formed much of the lowland areas. These processes have led to a high level of endemism and the area supports the highest level of biodiversity in the region. The area also contains fossil sites that record the evolution of life on New Guinea. -

Synthesis Report on Ten ASEAN Countries Disaster Risks Assessment

Synthesis Report on Ten ASEAN Countries Disaster Risks Assessment ASEAN Disaster Risk Management Initiative December 2010 Preface The countries of the Association of Southeast (Vietnam) droughts, September 2009 cyclone Asian Nations (ASEAN), which comprises Brunei, Ketsana (known as Ondoy in the Philippines), Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, catastrophic flood of October 2008, and January Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, is 2007 flood (Vietnam), September 1997 forest-fire geographically located in one of the most disaster (Indonesia) and many others. Climate change is prone regions of the world. The ASEAN region expected to exacerbate disasters associated with sits between several tectonic plates causing hydro-meteorological hazards. earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis. The region is also located in between two great Often these disasters transcend national borders oceans namely the Pacific and the Indian oceans and overwhelm the capacities of individual causing seasonal typhoons and in some areas, countries to manage them. Most countries in tsunamis. The countries of the region have a the region have limited financial resources and history of devastating disasters that have caused physical resilience. Furthermore, the level of economic and human losses across the region. preparedness and prevention varies from country Almost all types of natural hazards are present, to country and regional cooperation does not including typhoons (strong tropical cyclones), exist to the extent necessary. Because of this high floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, vulnerability and the relatively small size of most landslides, forest-fires, and epidemics that of the ASEAN countries, it will be more efficient threaten life and property, and droughts that leave and economically prudent for the countries to serious lingering effects. -

Rattan Field Guide Change Style-Edit Last New:Layout 1.Qxd

Contents Page Foreword Acknowledgement 1- Introduction . .1 2- How to use this book . 1 3- Rattan in Cambodia . .1 4- Use . .2 5- Rattan ecology and habitat . 2 6- Rattan characters . 3 6.1 Habit . 4 6.2 Stem/can . .4 6.3 Leaf Sheath . .4 6.4 Leave and leaflet . 6 6.5 Climbing organ . .8 6.6 Inflorescence . .9 6.7 Flower . .10 6.8 Fruit . .11 7- Specimen collection . .12 7.1 Collection method . 12 7.2 Field record . .13 7.3 Maintenance and drying . 13 8- Local names . .14 9- Key Identification to rattan genera . 17 9.1 Calamus L. .18 9.2 Daemonorops Bl. 44 9.3 Korthalsia Bl. 48 9.4 Myrialepis Becc. 52 9.5 Plectocomia Mart. ex Bl. 56 9.6 Plectocomiopsis Becc. 62 Table: Species list of Cambodia Rattan and a summary of abundance and distribution . .15 Glossary . 66 Reference . 67 List of rattan species . .68 Specimen references . .68 FOREWORD Rattan counts as one of the most important non-timber forest products that contribute to livelihoods as source of incomes and food and also to national economy with handicraft and furniture industry. In Cambodia, 18 species have been recorded so far and most of them are daily used by local communities and supplying the rattan industry. Meanwhile, with rattan resources decreasing due to over-harvesting and loss of forest ecosystem there is an urgent need to stop this trend and find ways to conserve this biodiversity that play an important economic role for the country. This manual is one step towards sustainable rattan management as it allows to show/display the diversity of rattan and its contribution.