Richard III and the Origins of the Court of Requests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) 3 Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) George M

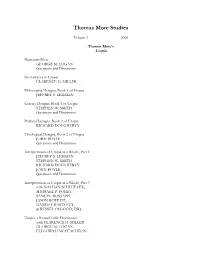

Thomas More Studies Volume 1 2006 Thomas More’s Utopia Humanist More GEORGE M. LOGAN Questions and Discussion No Lawyers in Utopia CLARENCE H. MILLER Philosophic Designs, Book 1 of Utopia JEFFREY S. LEHMAN Literary Designs, Book 1 of Utopia STEPHEN W. SMITH Questions and Discussion Political Designs, Book 2 of Utopia RICHARD DOUGHERTY Theological Designs, Book 2 of Utopia JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 1 JEFFREY S. LEHMAN STEPHEN W. SMITH RICHARD DOUGHERTY JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 2 with NATHAN SCHLUETER, MICHAEL P. FOLEY, SAMUEL BOSTAPH, JASON BOFETTI, GABRIEL BARTLETT, & RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Utopia, a Round Table Discussion with CLARENCE H. MILLER GEORGE M. LOGAN ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON The Development of Thomas More Studies Remarks CLARENCE H. MILLER ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON GEORGE M. LOGAN Interrogating Thomas More Interrogating Thomas More: The Conundrums of Conscience STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Response JOSEPH KOTERSKI, SJ Reply STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Questions and Discussion Papers On “a man for all seasons” CLARENCE H. MILLER Sir Thomas More’s Noble Lie NATHAN SCHLUETER Law in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia as Compared to His Lord Chancellorship RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Variations on a Utopian Diversion: Student Game Projects in the University Classroom MICHAEL P. FOLEY Utopia from an Economist’s Perspective SAMUEL BOSTAPH These are the refereed proceedings from the 2005 Thomas More Studies Conference, held at the University of Dallas, November 4-6, 2005. Intellectual Property Rights: Contributors retain in full the rights to their work. George M. Logan 2 exercises preparing himself for the priesthood.”3 The young man was also extremely interested in literature, especially as conceived by the humanists of the period. -

Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: the Ne Glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607 Daniel R

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 1981 Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The nE glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607 Daniel R. Coquillette Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Coquillette. "Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The nE glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607." Boston University Law Review 61, (1981): 1-89. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 61 NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1981 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW LEGAL IDEOLOGY AND INCORPORATION I: THE ENGLISH CIVILIAN WRITERS, 1523-1607t DANIEL R. COQUILLETTE* "And sure I am that no man can either bring over those bookes of late written (which I have seene) from Rome or Romanists, or read them, and justifie them, or deliver them over to any other with a liking and allowance of the same (as the author's end and desire is they should) but they runne into desperate dangers and downefals .... These bookes have glorious and goodly titles, which promise directions for the conscience, and remedies for the soul, but there is mors in olla: They are like to Apothecaries boxes... whose titles promise remedies, but the boxes themselves containe poyson." Sir Edward Coke "A strange justice that is bounded by a river! Truth on this side of the Pyrenees, error on the other side." 2 Blaise Pascal This Article initiates a three-part series entitled Legal Ideology and In- corporation. -

Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System George Jarvis Thompson

Cornell Law Review Volume 17 Article 1 Issue 2 February 1932 Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System George Jarvis Thompson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation George Jarvis Thompson, Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System, 17 Cornell L. Rev. 203 (1932) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol17/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORNELL LAW QUARTERLY VOLUME XVII FEBRUARY, 1932 NUMBER 2 THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANGLO-AMERICAN JIUDICIAL SYSTEM* GEORGE JARVIS THOMPSONt PART I HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH COURTS TO THE JUDICATURE ACTS b. The PrerogativeCourts 6"' In post-Conquest England, as in most primitive societies, the king as the fountain of justice and supreme administrator of the laws decided each case before him according to his royal will, exercising a prerogative or extraordinary jurisdiction much like the oriental justice of the Arabian Nights tales1 70 With respect to the conquered English, the king's justice in this period was always extraordinary. *Copyright, 1932, by George Jarvis Thompson. This article is the second installment of Part I of a historical survey of the Anglo-American judicial system. The first installment appeared in the December, 1931, issue of the CORNELL LAW QUARTERLY. It is expected that the succeeding installments of Part I will appear in subsequent issues of this volume. -

The Seventeenth-Century Revolution in the English Land Law

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 4 1995 The Seventeenth-Century Revolution in the English Land Law Charles J. Reid Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Land Use Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Charles J. Reid Jr., The Seventeenth-Century Revolution in the English Land Law, 43 Clev. St. L. Rev. 221 (1995) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol43/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION IN THE ENGLISH LAND LAW CHARLES J. REID, JR.1 INTRODUCTION ..................................... 223 I. THE ENGLISH REVOLUTION ........................... 225 A. A Schematic Chronology of the Revolution .......... 225 B. The Gentry and Revolution ...................... 230 II. THE ABOLITION OF THE FEUDAL INCIDENTS AND THE TRIUMPH OF SOCAGE TENURE ......................... 232 A. Origins of Knight Service and Wardship ........... 234 B. The Sixteenth-Century Revival of the Feudal Incidents .................................... 237 C. PopularResistance to the Feudal Incidents and the Eradicationof the Practice .................... 240 Ill. THE ENCLOSURE MOVEMENT, THE DOMESTICATION OF COPYHOLD, AND THE DESTRUCTION OF RIGHTS IN COMMON .... 243 A. Background to the EnclosureMovement of the Seventeenth Century .......................... 243 B. The Attack on Copyhold ........................ 246 1. Fifteenth-Century Conditions ............... 246 2. The Creation and Judicial Protection of Copyhold ................................. 247 3. -

DAVID STARKEY Court, Council, and Nobility in Tudor England

DAVID STARKEY Court, Council, and Nobility in Tudor England in RONALD G. ASCH AND ADOLF M. BIRKE (eds.), Princes, Patronage, and the Nobility: The Court at the Beginning of the Modern Age c.1450-1650 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991) pp. 175–203 ISBN: 978 0 19 920502 7 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 7 Court, Council, and Nobility in Tudor England DAVID STARKEY 'IT is difficult to realize that the king's Council was part of the king's household, ... and that we have to trace the develop- ment of the Council with the help of household books and ordinances.' This is A. F. Pollard's most striking insight into the history of the council. It is also the one that has least affected the historiography. This chapter aims to redress the balance by treating the development of the Tudor privy council as an aspect of the history of the Tudor court. -

Women in Chancery: an Analysis of Chancery As a Court of Redress for Women in Late Seventeenth Century England

The University of Hull The National Archives The Arts and Humanities Research Council Women in Chancery: An Analysis of Chancery as a Court of Redress for Women in Late Seventeenth Century England Being a thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Hull and The National Archives by Charlotte Garside (BA, MA) 201007894 June 2019 1 Contents Page List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………………...…..4 List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………………………………4 List of Abbreviations………………………………………………………………………………...…….7 Acknowledgements and Dedication ………………………………………………………………...8 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………….…12 1.1 The Court of Chancery…………………………………………………………………………..…16 1.2 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………26 2. Literature Review: Women and the Law in Early Modern England…….....43 2.1 The Female Legal Experience…………………………………………………………………...43 2.2 Female Legal Knowledge……………………………………………………………………….…48 2.3 Quantitative Historiography.................................................................................................65 3. Quantitative Analysis: Women in Chancery…………………………………………....74 3.1 Plaintiffs……………………………………………………………………………………………….…75 3.2 Defendants………………………………………………………………………………………….…..86 3.3 Depositions…………………………………………………………………………………………..…92 3.4 Types of Suits……………….………………………………………………………………………....94 3.5 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………….100 4. The Experience of Singlewoman in Chancery………………………………………105 4.1 -

Cromwelliana

Cromwelliana The Cromwell Association 1990 ~ ...>~~t1 CROMWELLIANA 1990 edited by Peter Gaunt The Cromwell Association ~ President: Dr JOHN MORRILL •••• ~ Vice-Presidents: THE LORD CARADON OF ST CLEER CONTENTS Professor IVAN ROOTS ~ page Dr MAURICE ASHLEY, C.B.E. CROMWELL'S DAY 1989. By Robert Ashton ~ 2 Dr E.S. DE BEER, C.B.E. STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: OLIVER CROMWELL, JOHN GOODWIN AND .L-:t 1 THE CRISIS_ OF CALVINISM. By Tom Webster 7 Miss HILARY PLATT GOD'S ENGLISHMAN: OLIVER CROMWELL. Part One. By Glyn Brace Jones 17 Chainnan: Mr TREWIN COPPLESTONE HER HIGHNESS'S COURT. By Sarah Jones Hon. Secretary: Miss PAT BARNES '. .•i-•·J:I 20 Cosswell Cottage, North edge, Tupton, Chesterfield, S42 6AY OLIVER CROMWELL AND SwEDEN'S KING CHARLES X GUsTAVUS· 25 :J~t· ENGlA'.ID, SWEDEN AND THE PROTESTANT INTERNATIONAL . Hon. Treasurer: Mr JOHN WESTMACOTT By Bertil Haggman · . , · Salisbury Close, Wokingham, Berks, RGll 4AJ :J~<C BEATING UP QUARTERS. By Keith.Robert~ Hon. Editor of Cromwe//iana: Dr PETER GAUNT 29 G ... THE MATCHLEsS ORINDA: MRS KA~ PHILIPS 1631-64 -•c By John Atkins · ' · . 33 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt. Hon. Isaac Foot ~ CRO~WELLIAN FACT IN MALOON, ESSEX. and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan statesman, and to encourage By Michael Byrd 35 the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims ~J~'.°;b CROMWELLIAN BRITAIN ill: APPLEBY,. CUMBRIA in a variety of ways which have included: . -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Grief As Medicine for Grief: Complaint Poetry in Early Modern England, 1559-1609 a DISSERTATION SUBMITT

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Grief as Medicine for Grief: Complaint Poetry in Early Modern England, 1559-1609 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of English By Joanne Teresa Diaz EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2008 2 © Copyright by Joanne Teresa Diaz 2008 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Grief as Medicine for Grief: Early Modern Complaint Poetry in England, 1559-1609 Joanne Teresa Diaz This dissertation traces the meaning and scope of early modern complaint poetry. I argue that what I understand as a secular “poetics of dissatisfaction” arose to fill the void left when religious auricular confession was no longer an institutionalized practice, and that this mode of literary expression was itself shaped by the evolving legal discourse of complaining. These articulations of dissatisfaction cross genre, style, and medium, but they all share a common language with two prominent discourses: the penitential literature of the Reformation, which worked to refigure confession when it was no longer a sacrament; and juridical testimony, which regularly blurred the line between auricular confession in the ecclesiastical courts and secular jurisprudence in the common law courts. Complaint poetry investigates questions about evidence, sincerity, and the impossibility of ever doing—or saying—enough about despair; it also considers the imaginative implications of a post-Reformation world in which the remedy for despair might be its poetic expression. Critics have long seen emergent interiority as a defining characteristic of early modern poetry; however, I argue that complaint poems are argumentative, highly emotional, and committed to revealing a shattered self in publicly staged distress. -

The Separation of Law and Equity and the Arkansas Chancery Courts: Historical Anomalies and Political Realities

University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review Volume 17 Issue 2 Symposium on Arkansas Law: The Article 2 Arkansas Courts 1995 The Separation of Law and Equity and the Arkansas Chancery Courts: Historical Anomalies and Political Realities Morton Gitelman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Morton Gitelman, The Separation of Law and Equity and the Arkansas Chancery Courts: Historical Anomalies and Political Realities, 17 U. ARK. LITTLE ROCK L. REV. 215 (1995). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol17/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review by an authorized editor of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEPARATION OF LAW AND EQUITY AND THE ARKANSAS CHANCERY COURTS: HISTORICAL ANOMALIES AND POLITICAL REALITIES Morton Gitelman' Separate courts of equity have largely passed from the legal scene in both England and the United States. Arkansas, however, still maintains the separation. The purpose of this article is to explain the historical background of the Anglo-American phenomenon of separate courts of equity and to explore the reasons in favor of and prospects for changing the current system, or merging law and equity into a unitary court system. When Joseph Story published his brilliant commentaries on equity in 1835, he stated: "The Origin of the Court of Chancery is involved in the same obscurity, which attends the investigation of many other questions, of high antiquity, relative to the Common Law." ' 2 The obscurity referred to is only in the sense of the paucity of records concerning the work of the English Chancellors for the greater part of the history of the English courts. -

Conscience and the King's Household Clergy in the Early Tudor Court Of

Conscience and the King’s Household Clergy in the Early Tudor Court of Requests Laura Flannigan* Newnham College, Cambridge The early Tudor Court of Requests was closely attached to the king’s person and his duty to provide ‘indifferent’ justice. In practice, however, it was staffed by members of the attendant royal household and council. Utilizing the little-studied but extensive records of the court, this article traces the rising dominance of the dean of the Chapel Royal and the royal almoner as administrators and judges there from the 1490s to the 1520s. It exam- ines the relationship between supposedly ‘secular’ and ‘spiritual’ activities within the central administration and between the formal and informal structures and ideologies of the church, the law and the royal household. It explores the politics of proximity and the ad hoc nature of early Tudor governance which made the conscience-based jurisdiction in Requests especially convenient to the king and desperate litigants alike. Overall the article argues that although the influence of clergymen in the court waned towards the end of the sixteenth century in favour of common-law judges, its enduring association with ‘poor men’scauses’ and ‘conscience’ grew directly from these early clerical underpinnings. In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, litigants without remedy at the rigid English common law could increasingly sue to the king’s extraordinary justice. This justice was executed within an expanding range of distinct central tribunals, including the courts of Chancery and Star Chamber as well as the little-studied Court of Requests, which emerged as the judicial arm of the attendant royal council in the late fifteenth century. -

The Tudor Privy Council, C. 1540–1603

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Tudor Privy Council, c. 1540–1603 Dr David J. Crankshaw King’s College London Various source media, State Papers Online EMPOWER™ RESEARCH THE TUDOR PRIVY COUNCIL, C. staff, not least the clerks, whose unrelenting labours [1] kept the operational wheels turning. The sixteenth- 1540–1603 century history of the Privy Council has not been uncontroversial; two major debates are sketched below. The essay concludes with some ‘Notes on Using Introduction the Privy Council Registers’ because there are potential No matter what aspect of later Tudor history we care to pitfalls for readers unused to Tudor primary sources, investigate, we cannot afford to ignore the Privy and especially for those who may consult the Council.[2] In Sir Geoffrey Elton’s words, it was ‘the manuscripts with reference to the Victorian-Edwardian [5] centre of administration, the instrument of policy publication entitled Acts of the Privy Council. If the making, the arena of political conflict, and the ultimate essay tends to draw examples from Elizabeth’s reign, means for dispensing the king’s justice’, an institution then that is partly because it constituted the bulk of the at once ‘essential’ and ‘inescapable’.[3] David Dean calls period under review and partly because materials it ‘the most important policy-making and administrative relating to the years 1558–1603 are those with which institution of Elizabethan government’. He quotes the author is most familiar. approvingly Thomas Norton (d. 1584), a busy conciliar The Late Medieval King’s Council and the Emergence agent, who claimed that the Privy Council was ‘the of the Privy Council wheels that hold the chariot of England upright’.[4] In many ways, it was significantly different to the Councils England’s medieval kings had a council, but not a Privy of France and Spain: they could only advise action, Council in the Tudor sense. -

A History of Injunctions in England Before 1700

Indiana Law Journal Volume 61 Issue 4 Article 1 Fall 1986 A History of Injunctions in England Before 1700 David W. Raack Ohio Northern University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Raack, David W. (1986) "A History of Injunctions in England Before 1700," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 61 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol61/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indiana __ Law :5 Journal Vol. 61, No.4 CCC~ 1985-1986 A History of Injunctions in England Before 1700* DAviD W. RAACK** INTRODUCTION The injunction has been called the quintessential equitable remedy.' This article will examine the history of this equitable remedy before 1700. First, several of the injunction's possible forerunners, in ancient Roman law and in the equity administered by the early English common law courts, will be discussed. The article will then trace the development of injunctions in England until the end of the 1600's. The rules of injunctions, like the rules of equity generally,2 were a product of the institution of the Court of Chancery, and this account of the evolution of injunctions will necessarily entail an account of the growth of Chancery from its origin as an administrative office to its emergence as a judicial body.