A History of Injunctions in England Before 1700

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641 Nathaniel A

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2018 "This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641 Nathaniel A. Earle Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Earle, Nathaniel A., ""This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641" (2018). All Theses. 2950. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2950 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS COURT DOTH KEEP ALL ENGLAND IN QUIET" STAR CHAMBER AND PUBLIC EXPRESSION IN PREREVOLUTIONARY ENGLAND 1625–1641 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Nathaniel A. Earle August 2018 Accepted by: Dr. Caroline Dunn, Committee Chair Dr. Alan Grubb Dr. Lee Morrissey ABSTRACT The abrupt legislative destruction of the Court of Star Chamber in the summer of 1641 is generally understood as a reaction against the perceived abuses of prerogative government during the decade of Charles I’s personal rule. The conception of the court as an ‘extra-legal’ tribunal (or as a legitimate court that had exceeded its jurisdictional mandate) emerges from the constitutional debate about the limits of executive authority that played out over in Parliament, in the press, in the pulpit, in the courts, and on the battlefields of seventeenth-century England. -

Delaware Chancery Court Review

State of Connecticut Judicial Branch Court Operations Unit Quality Assurance, Performance Measures & Statistics Joseph Greelish, Deputy Director (phone) 860-263-2734 (fax) 860-263-2773 Delaware Chancery Court Review “The arbiter of corporate conflicts and fiduciary disputes and equity matters, all under the mantle of "institutionalized fairness". -Sam Glasscock, Vice Chancellor Delaware Chancery Court Background and Jurisdiction • Delaware created its Court of Chancery in 1792 bucking a national trend away from Chancery Courts. • Article IV, Section 10 of the Delaware Constitution establishes the Court and provides that it "shall have all the jurisdiction and powers vested by the laws of this State in the Court of Chancery." The Court has one Chancellor, who is the chief judicial officer of the Court, and four Vice Chancellors. It also has two Masters in Chancery, who are assigned by the Chancellor and Vice Chancellors to assist in matters as needed. • The Court of Chancery has jurisdiction to hear all matters relating to equity. o The Court cannot grant relief in the form of money damages to compensate a party for a loss or where another court has coterminous jurisdiction. o However, under the rules of equity, the court can grant monetary relief in the form of restitution by ruling that another party has unjustly gained money that belongs to the plaintiff. • Apart from its general equitable jurisdiction, the Court has jurisdiction over a number of other matters. The Court has sole power to appoint guardians of the property and person for mentally or physically disabled Delaware residents. Similarly, the Court may also appoint guardians for minors, although the Family Court has coterminous jurisdiction over such matters. -

PLEASE NOTE This Is a Draft Paper Only and Should Not Be Cited Without

PLEASE NOTE This is a draft paper only and should not be cited without the author’s express permission THE SHORT-TERM IMPACT OF THE >GLORIOUS REVOLUTION= ON THE ENGLISH JUDICIAL SYSTEM On February 14, 1689, The day after William and Mary were recognized by the Convention Parliament as King and Queen, the first members of their Privy Council were sworn in. And, during the following two to three weeks, all of the various high offices in the government and the royal household were filled. Most of the politically powerful posts went either to tories or to moderates. The tory Earl of Danby was made Lord President of the Council and another tory, the Earl of Nottingham was made Secretary of State for the Southern Department. The office of Lord Privy Seal was given to the Atrimming@ Marquess of Halifax, whom dedicated whigs had still not forgiven for his part in bringing about the disastrous defeat of the exclusion bill in the Lords= house eight years earlier. Charles Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, who was named Principal Secretary of State, can really only be described as tilting towards the whigs at this time. But, at the Admiralty and the Treasury, both of which were put into commission, in each case a whig stalwart was named as the first commissioner--Lord Mordaunt and Arthur Herbert respectivelyBand also in each case a number of other leading whigs were named to the commission as well.i Whig lawyers, on the whole, did rather better than their lay fellow-partisans. Devonshire lawyer and Inner Temple Bencher Henry Pollexfen was immediately appointed Attorney- General, and his cousin, Middle Templar George Treby, Solicitor General. -

Pdfsussex County Opening Brief in Motion to Dismiss

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE DELAWAREANS FOR ) EDUCATIONAL ) OPPORTUNITY and NAACP ) DELAWARE STATE ) C.A. No. 2018-0029-JTL CONFERENCE OF ) BRANCHES, ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) JOHN CARNEY, Governor of ) the State of Delaware; SUSAN ) BUNTING, Secretary of ) Education of the State of ) Delaware; KENNETH A. ) SIMPLER, Treasurer of the ) State of Delaware; SUSAN ) DURHAM, Director of ) Finance of Kent County, ) Delaware; BRIAN ) MAXWELL, Chief Financial ) Officer of New Castle County, ) Delaware; and GINA ) JENNINGS, Finance Director ) for Sussex County, ) Defendants. ) DEFENDANT GINA JENNINGS’ OPENING BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF HER MOTION TO DISMISS THE VERIFIED COMPLAINT PURSUANT TO COURT OF CHANCERY RULE 12(B)(6). MARGOLIS EDELSTEIN /s/ Herbert W. Mondros Herbert W. Mondros, Esq. ID No. 3308 Helene Episcopo, Esq. ID No. 6406 300 Delaware Ave., Suite 800 Wilmington, DE 19801 (302) 888-1112 Email:[email protected] Counsel to Defendant Gina Jennings DATED: April 13, 2018 Table of Contents I. Nature and Stage of Proceedings…………………..……………………… 1 II. Statement of Relevant Facts…………………………………………….… 3 III. Questions Involved……………………..…………………………….….... 7 IV. Argument…………………………………………………………………. 8 A. Standards for a Motion to Dismiss Under Rule 12(b)(6)……….…. 8 B. The Court of Chancery Lacks Subject Matter Jurisdiction Over This Case Because Adequate Remedies At Law Exist. )………………. 9 1. This Court Lack Subject Matter Jurisdiction Over This Declaratory Judgment Action Because There Is No Underlying Basis for Equity Jurisdiction……………….……………….. 9 2. This Court Lack Subject Matter Jurisdiction Over This Case Because Plaintiffs Are Truly Seeking A Writ of Mandamus..15 C. Counts I, II, and III Should Be Dismissed Because Plaintiffs Complaint Seeks An Advisory Opinion Disguised As Declaratory Relief.…..………….……………………………………………… 16 D. -

The Accomplish'd Practiser in the High Court of Chancery (1790)

• • , • THE • , ccom 1 Pra , • IN TH E (lCOUlt of SHEWING The whole Method of Proceedings, according to the prefent Practice, from the Bill to the AppeaJ, inclufive. CONTAINING , The Original Power aml JurifdiC1ion of the Chancery, both as a Court of Law and Equity; the Office of the Lord Chancel lor, lVIall:er vf the Rolls, and the rell: of the Officers: A L SO The beft Forms and Precedents of Bills, Anfwers, Pleas, Demurrers, WI>S, Commifiions, Interrogatories, Aflidavits, Petitions, ami Order; : TOGETHER WITH A LIST of the OFFICERS and their Fees: LIKeWISE Other MATTERS urduJ for PRACTISIlRS. I . .I 7 T " . • • , // C I' By JOSEPH H~gRISON of Lincoln's Inn, Efq. I " .- - • • • I The SEVENTH EDITION, (being a new one) upon • Plan din.tent frolll that purfucd in the forDlcr Editions of this \Vork; with all the IIJatticc enJargcd under 'every Head, and an adJition of Precedents of all kinds; the P(oceedjng~ upon a Conlmillion of Lunacy; with additional Notes and References to the Ancient and f'Aouern Reports in Equity. By JOHN GRIFFITH WILLIAMS, ECq. Of Lincoln's Inn, Barrifter at Law. • • . ... IN TWO VOL U M E S. , VOL. I. " LON DON: PRINTED BY A. STRAHAN AND W. WOODFALL, I,AW-PRINTERS TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY; fOR T. WHIELDON, IN FLEET-STREET; AND R. PHIlNEY, IN lNNER TEMPLE LANll. ( 1790 • c ' • " IDf tbe ~OUtt of ~bancet~. Soifa bill be touching titles afland, not more than fix acres, Mor. 356. nnd not of the yearly value of forty lhillings, upon /hewing this to the court by affidavit, the caufe will ordinarily be difmilfed. -

Business Courts

THE “NEW”BUSINESS COURTS by Lee Applebaum1 Lawyer 1: “I’ll say a phrase and you name the first court that comes to mind.” Lawyer 2: “Ok, go.” Lawyer 1: “Business Court.” Lawyer 2: “Delaware Court of Chancery.” Fifteen years ago, the over two hundred year old Delaware Court of Chancery would have been the only response; but today other possibilities exist. If this same word association test was conducted in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston or Charlotte, to name a few cities, the subconscious link from the phrase “business court” would no longer inexorably lead to Delaware. For nearly 15 years, various states’ trial courts have incorporated specialized business and commercial tracks within their dockets, often starting as pilot programs. Some of these experiments have become institutionalized, with “business courts” operating for over a decade in Manhattan, Chicago and North Carolina. Other business courts -- in Rhode Island, Philadelphia, Las Vegas, Reno, and Boston -- are on their way to the ten year mark; and a new generation has arisen in the last few years. Delaware’s Court of Chancery remains the bright star in this firmament, and it sets the standard to which other courts aspire: to institutionalize the qualities that make Chancery a great court. Hard work, long development and study of legal issues, intelligence and integrity are the foundation of its excellence, forming the qualitative archetype for the new business courts. Chancery’s “aspirational model” goes more to the essence than the attributes of these “new” business courts, however, which have taken a distinctly different form. They are not courts of equity focusing on corporate governance and constituency issues, though these issues form part of their jurisdiction. -

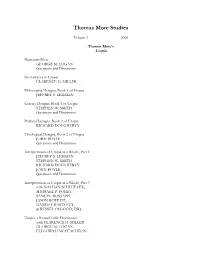

Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) 3 Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) George M

Thomas More Studies Volume 1 2006 Thomas More’s Utopia Humanist More GEORGE M. LOGAN Questions and Discussion No Lawyers in Utopia CLARENCE H. MILLER Philosophic Designs, Book 1 of Utopia JEFFREY S. LEHMAN Literary Designs, Book 1 of Utopia STEPHEN W. SMITH Questions and Discussion Political Designs, Book 2 of Utopia RICHARD DOUGHERTY Theological Designs, Book 2 of Utopia JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 1 JEFFREY S. LEHMAN STEPHEN W. SMITH RICHARD DOUGHERTY JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 2 with NATHAN SCHLUETER, MICHAEL P. FOLEY, SAMUEL BOSTAPH, JASON BOFETTI, GABRIEL BARTLETT, & RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Utopia, a Round Table Discussion with CLARENCE H. MILLER GEORGE M. LOGAN ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON The Development of Thomas More Studies Remarks CLARENCE H. MILLER ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON GEORGE M. LOGAN Interrogating Thomas More Interrogating Thomas More: The Conundrums of Conscience STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Response JOSEPH KOTERSKI, SJ Reply STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Questions and Discussion Papers On “a man for all seasons” CLARENCE H. MILLER Sir Thomas More’s Noble Lie NATHAN SCHLUETER Law in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia as Compared to His Lord Chancellorship RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Variations on a Utopian Diversion: Student Game Projects in the University Classroom MICHAEL P. FOLEY Utopia from an Economist’s Perspective SAMUEL BOSTAPH These are the refereed proceedings from the 2005 Thomas More Studies Conference, held at the University of Dallas, November 4-6, 2005. Intellectual Property Rights: Contributors retain in full the rights to their work. George M. Logan 2 exercises preparing himself for the priesthood.”3 The young man was also extremely interested in literature, especially as conceived by the humanists of the period. -

Taht Ve the Throne and Papal Relations in the Framework

e-ISSN: 2149-3871 TAHT VE * , . (2020). Provisors ve Praemunire v . Kabul Tarihi: 14.03.2021 , E-ISSN: 2149-3871 10(2), 331-342. DOI: https://doi.org/10.30783/nevsosbilen.890858 si, Fen-Edebiyat si, Tarih [email protected] ORCID No: 0000-0002- 1587-657X si, [email protected] ORCID No: 0000-0002-6076-6994 ve 1353 - Anahtar Kelimeler: THE THRONE AND PAPAL RELATIONS IN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE STATUTE OF PROVISORS AND PRAEMUNIRE LAWS ABSTRACT In the Middle Ages, the kingdom and the scene of rivalry and conflict with each other are frequently encountered.Therefore, the same situation is seen in the Middle Ages England.Because the Church was an institution legally attached to the Papacy.Kings and Popes were lords to whom the British clergy offered their loyalty and allegiance.In addition, his men and religious institutions were influential in economic life in medieval England.The claims of the Church, which has broad authority over the laws, caused it to be lived in a conflict zone.The most important to begin with are the Provisors Law in 1351 and the Praemunire laws enacted in 1353, which were a turning point in the relations between the kingdom and the papacy. With these laws, the anti-papacy feeling of enlargement has become evident since the beginning of the third century and has made itself permanent in the laws of the region.In this market, the power conflict between the Kingdom and the Church will be studied to be evaluated within the framework of these laws. Keywords:Middle Age, England,The Statute of Provisors, Papacy, The Statute of Praemunire. -

The Right of Silence

Review The Right of Silence Neill H. Alford, Jr.t Origins of the Fifth Amendment: The Right Against Self-Incrimina. tion. By Leonard W. Levy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968. Pp. xii, 561. $12.50. "Freeborn" John Lilburne defied his first "establishment" at the age of seventeen. He sued Hewson, the master to whom he was appren- ticed, before the Lord Chamberlain of London for showering abuse upon him. During the stormy years which followed, Lilburne tilted with the Star Chamber, committees of the House of Commons, the Council of State and Cromwell's judicial commissioners. He wore himself out by his determined opposition to those in power at the comparatively early age of forty-three. Had this not occurred, Lil- burne certainly would have made Charles II a "gloomy" rather than a "merry" monarch. Perhaps he would have ended his days, not in prison at Dover, but banished to Massachusetts, where those who of- fended Charles were likely to be sent. There he unquestionably would have contributed to the already considerable discomforts of the Pil- grim Fathers. When, in 1637, Lilburne was arrested at the age of twenty-three by pursuivants of the Stationers' Company and tried before the Star Chamber for shipping seditious books from Holland to England, he stoutly refused to take the ex officio oath on the ground he should not be made to accuse himself. The Court of Star Chamber consisted of the judicial members of the Privy Council. At the time Lilburne was brought before it, the Court had a reputation for fairness in proce- dure and speed in decision-making that attracted many litigants to it from the common law courts. -

The Great Statute of Praemunire Downloaded From

1922 173 The Great Statute of Praemunire Downloaded from HE so-called statutes of praemunire are among the most T famous laws in English history, and of the three acts to which the title is commonly applied, that of 1393—sometimes http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ called ' the great statute of praemunire ' by modern writers1— has won special renown, partly because it has been generally regarded as an anti-papal enactment of singular boldness, and also because it furnished Henry Vlil with perhaps the most formidable of the weapons used by him to destroy Wolsey and to intimidate the clergy. But when the student, anxious to know precisely what the statute contained and what it was designed to effect, turns for light to the works of modern historians, he finds at University of California, San Diego on August 28, 2015 himself faced by a perplexing variety of opinions. Stubbs, who in one place * says bluntly that ' the great statute of praemunire imposed forfeiture of goods as the penalty for obtaining bulls or other instruments at Rome ', elsewhere 3 restricts its effect to those who procured bulls, instruments, or other things ' which touch the king, his crown, regality, or realm ', while in another passage * he states that though the statute allowed appeals to Rome ' in causes for which the English common law provided no remedy ', it nevertheless contributed to a great diminution in the number of such appeals. In other works one may read that ' the great statute of Praemunire was the most anti-papal Act of Parliament passed prior to the reign of Henry Vlil; the Act from which the rapid decline of Papal authority in England is commonly dated ' ; 6 that by the statute ' papal interference was shut out [of England] as far as law could shut it out' ; * or that with its predecessors of 1353 and 1365 it ranked as 'the great bulwark of the independence of the National Church '.7 On the other hand, Makower, speaking of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, says : ' Only in so far as was necessary for the execution of the statutes against provisors was the endeavour 1 e.g. -

Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: the Ne Glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607 Daniel R

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 1981 Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The nE glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607 Daniel R. Coquillette Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Coquillette. "Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The nE glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607." Boston University Law Review 61, (1981): 1-89. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 61 NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1981 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW LEGAL IDEOLOGY AND INCORPORATION I: THE ENGLISH CIVILIAN WRITERS, 1523-1607t DANIEL R. COQUILLETTE* "And sure I am that no man can either bring over those bookes of late written (which I have seene) from Rome or Romanists, or read them, and justifie them, or deliver them over to any other with a liking and allowance of the same (as the author's end and desire is they should) but they runne into desperate dangers and downefals .... These bookes have glorious and goodly titles, which promise directions for the conscience, and remedies for the soul, but there is mors in olla: They are like to Apothecaries boxes... whose titles promise remedies, but the boxes themselves containe poyson." Sir Edward Coke "A strange justice that is bounded by a river! Truth on this side of the Pyrenees, error on the other side." 2 Blaise Pascal This Article initiates a three-part series entitled Legal Ideology and In- corporation. -

Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System George Jarvis Thompson

Cornell Law Review Volume 17 Article 1 Issue 2 February 1932 Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System George Jarvis Thompson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation George Jarvis Thompson, Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System, 17 Cornell L. Rev. 203 (1932) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol17/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORNELL LAW QUARTERLY VOLUME XVII FEBRUARY, 1932 NUMBER 2 THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANGLO-AMERICAN JIUDICIAL SYSTEM* GEORGE JARVIS THOMPSONt PART I HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH COURTS TO THE JUDICATURE ACTS b. The PrerogativeCourts 6"' In post-Conquest England, as in most primitive societies, the king as the fountain of justice and supreme administrator of the laws decided each case before him according to his royal will, exercising a prerogative or extraordinary jurisdiction much like the oriental justice of the Arabian Nights tales1 70 With respect to the conquered English, the king's justice in this period was always extraordinary. *Copyright, 1932, by George Jarvis Thompson. This article is the second installment of Part I of a historical survey of the Anglo-American judicial system. The first installment appeared in the December, 1931, issue of the CORNELL LAW QUARTERLY. It is expected that the succeeding installments of Part I will appear in subsequent issues of this volume.