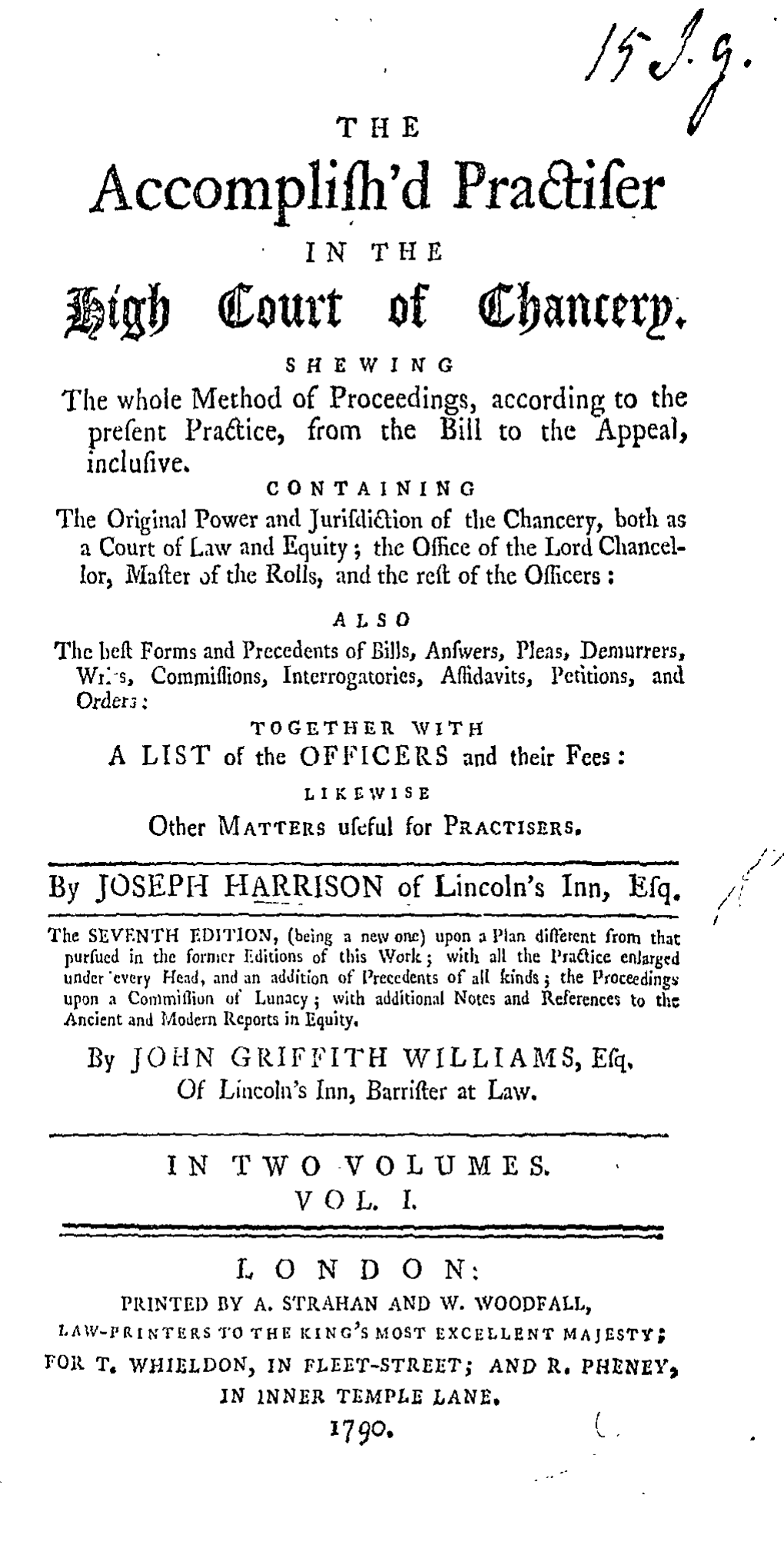

The Accomplish'd Practiser in the High Court of Chancery (1790)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641 Nathaniel A

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2018 "This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641 Nathaniel A. Earle Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Earle, Nathaniel A., ""This Court Doth Keep All England in Quiet": Star Chamber and Public Expression in Prerevolutionary England, 1625–1641" (2018). All Theses. 2950. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2950 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS COURT DOTH KEEP ALL ENGLAND IN QUIET" STAR CHAMBER AND PUBLIC EXPRESSION IN PREREVOLUTIONARY ENGLAND 1625–1641 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Nathaniel A. Earle August 2018 Accepted by: Dr. Caroline Dunn, Committee Chair Dr. Alan Grubb Dr. Lee Morrissey ABSTRACT The abrupt legislative destruction of the Court of Star Chamber in the summer of 1641 is generally understood as a reaction against the perceived abuses of prerogative government during the decade of Charles I’s personal rule. The conception of the court as an ‘extra-legal’ tribunal (or as a legitimate court that had exceeded its jurisdictional mandate) emerges from the constitutional debate about the limits of executive authority that played out over in Parliament, in the press, in the pulpit, in the courts, and on the battlefields of seventeenth-century England. -

Delaware Chancery Court Review

State of Connecticut Judicial Branch Court Operations Unit Quality Assurance, Performance Measures & Statistics Joseph Greelish, Deputy Director (phone) 860-263-2734 (fax) 860-263-2773 Delaware Chancery Court Review “The arbiter of corporate conflicts and fiduciary disputes and equity matters, all under the mantle of "institutionalized fairness". -Sam Glasscock, Vice Chancellor Delaware Chancery Court Background and Jurisdiction • Delaware created its Court of Chancery in 1792 bucking a national trend away from Chancery Courts. • Article IV, Section 10 of the Delaware Constitution establishes the Court and provides that it "shall have all the jurisdiction and powers vested by the laws of this State in the Court of Chancery." The Court has one Chancellor, who is the chief judicial officer of the Court, and four Vice Chancellors. It also has two Masters in Chancery, who are assigned by the Chancellor and Vice Chancellors to assist in matters as needed. • The Court of Chancery has jurisdiction to hear all matters relating to equity. o The Court cannot grant relief in the form of money damages to compensate a party for a loss or where another court has coterminous jurisdiction. o However, under the rules of equity, the court can grant monetary relief in the form of restitution by ruling that another party has unjustly gained money that belongs to the plaintiff. • Apart from its general equitable jurisdiction, the Court has jurisdiction over a number of other matters. The Court has sole power to appoint guardians of the property and person for mentally or physically disabled Delaware residents. Similarly, the Court may also appoint guardians for minors, although the Family Court has coterminous jurisdiction over such matters. -

PLEASE NOTE This Is a Draft Paper Only and Should Not Be Cited Without

PLEASE NOTE This is a draft paper only and should not be cited without the author’s express permission THE SHORT-TERM IMPACT OF THE >GLORIOUS REVOLUTION= ON THE ENGLISH JUDICIAL SYSTEM On February 14, 1689, The day after William and Mary were recognized by the Convention Parliament as King and Queen, the first members of their Privy Council were sworn in. And, during the following two to three weeks, all of the various high offices in the government and the royal household were filled. Most of the politically powerful posts went either to tories or to moderates. The tory Earl of Danby was made Lord President of the Council and another tory, the Earl of Nottingham was made Secretary of State for the Southern Department. The office of Lord Privy Seal was given to the Atrimming@ Marquess of Halifax, whom dedicated whigs had still not forgiven for his part in bringing about the disastrous defeat of the exclusion bill in the Lords= house eight years earlier. Charles Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, who was named Principal Secretary of State, can really only be described as tilting towards the whigs at this time. But, at the Admiralty and the Treasury, both of which were put into commission, in each case a whig stalwart was named as the first commissioner--Lord Mordaunt and Arthur Herbert respectivelyBand also in each case a number of other leading whigs were named to the commission as well.i Whig lawyers, on the whole, did rather better than their lay fellow-partisans. Devonshire lawyer and Inner Temple Bencher Henry Pollexfen was immediately appointed Attorney- General, and his cousin, Middle Templar George Treby, Solicitor General. -

Pdfsussex County Opening Brief in Motion to Dismiss

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE DELAWAREANS FOR ) EDUCATIONAL ) OPPORTUNITY and NAACP ) DELAWARE STATE ) C.A. No. 2018-0029-JTL CONFERENCE OF ) BRANCHES, ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) JOHN CARNEY, Governor of ) the State of Delaware; SUSAN ) BUNTING, Secretary of ) Education of the State of ) Delaware; KENNETH A. ) SIMPLER, Treasurer of the ) State of Delaware; SUSAN ) DURHAM, Director of ) Finance of Kent County, ) Delaware; BRIAN ) MAXWELL, Chief Financial ) Officer of New Castle County, ) Delaware; and GINA ) JENNINGS, Finance Director ) for Sussex County, ) Defendants. ) DEFENDANT GINA JENNINGS’ OPENING BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF HER MOTION TO DISMISS THE VERIFIED COMPLAINT PURSUANT TO COURT OF CHANCERY RULE 12(B)(6). MARGOLIS EDELSTEIN /s/ Herbert W. Mondros Herbert W. Mondros, Esq. ID No. 3308 Helene Episcopo, Esq. ID No. 6406 300 Delaware Ave., Suite 800 Wilmington, DE 19801 (302) 888-1112 Email:[email protected] Counsel to Defendant Gina Jennings DATED: April 13, 2018 Table of Contents I. Nature and Stage of Proceedings…………………..……………………… 1 II. Statement of Relevant Facts…………………………………………….… 3 III. Questions Involved……………………..…………………………….….... 7 IV. Argument…………………………………………………………………. 8 A. Standards for a Motion to Dismiss Under Rule 12(b)(6)……….…. 8 B. The Court of Chancery Lacks Subject Matter Jurisdiction Over This Case Because Adequate Remedies At Law Exist. )………………. 9 1. This Court Lack Subject Matter Jurisdiction Over This Declaratory Judgment Action Because There Is No Underlying Basis for Equity Jurisdiction……………….……………….. 9 2. This Court Lack Subject Matter Jurisdiction Over This Case Because Plaintiffs Are Truly Seeking A Writ of Mandamus..15 C. Counts I, II, and III Should Be Dismissed Because Plaintiffs Complaint Seeks An Advisory Opinion Disguised As Declaratory Relief.…..………….……………………………………………… 16 D. -

Business Courts

THE “NEW”BUSINESS COURTS by Lee Applebaum1 Lawyer 1: “I’ll say a phrase and you name the first court that comes to mind.” Lawyer 2: “Ok, go.” Lawyer 1: “Business Court.” Lawyer 2: “Delaware Court of Chancery.” Fifteen years ago, the over two hundred year old Delaware Court of Chancery would have been the only response; but today other possibilities exist. If this same word association test was conducted in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston or Charlotte, to name a few cities, the subconscious link from the phrase “business court” would no longer inexorably lead to Delaware. For nearly 15 years, various states’ trial courts have incorporated specialized business and commercial tracks within their dockets, often starting as pilot programs. Some of these experiments have become institutionalized, with “business courts” operating for over a decade in Manhattan, Chicago and North Carolina. Other business courts -- in Rhode Island, Philadelphia, Las Vegas, Reno, and Boston -- are on their way to the ten year mark; and a new generation has arisen in the last few years. Delaware’s Court of Chancery remains the bright star in this firmament, and it sets the standard to which other courts aspire: to institutionalize the qualities that make Chancery a great court. Hard work, long development and study of legal issues, intelligence and integrity are the foundation of its excellence, forming the qualitative archetype for the new business courts. Chancery’s “aspirational model” goes more to the essence than the attributes of these “new” business courts, however, which have taken a distinctly different form. They are not courts of equity focusing on corporate governance and constituency issues, though these issues form part of their jurisdiction. -

The Right of Silence

Review The Right of Silence Neill H. Alford, Jr.t Origins of the Fifth Amendment: The Right Against Self-Incrimina. tion. By Leonard W. Levy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968. Pp. xii, 561. $12.50. "Freeborn" John Lilburne defied his first "establishment" at the age of seventeen. He sued Hewson, the master to whom he was appren- ticed, before the Lord Chamberlain of London for showering abuse upon him. During the stormy years which followed, Lilburne tilted with the Star Chamber, committees of the House of Commons, the Council of State and Cromwell's judicial commissioners. He wore himself out by his determined opposition to those in power at the comparatively early age of forty-three. Had this not occurred, Lil- burne certainly would have made Charles II a "gloomy" rather than a "merry" monarch. Perhaps he would have ended his days, not in prison at Dover, but banished to Massachusetts, where those who of- fended Charles were likely to be sent. There he unquestionably would have contributed to the already considerable discomforts of the Pil- grim Fathers. When, in 1637, Lilburne was arrested at the age of twenty-three by pursuivants of the Stationers' Company and tried before the Star Chamber for shipping seditious books from Holland to England, he stoutly refused to take the ex officio oath on the ground he should not be made to accuse himself. The Court of Star Chamber consisted of the judicial members of the Privy Council. At the time Lilburne was brought before it, the Court had a reputation for fairness in proce- dure and speed in decision-making that attracted many litigants to it from the common law courts. -

Jury Trial of Issues in Equity Cases Before 1791

Chancery Procedure and the Seventh Amendment: Jury Trial of Issues in Equity Cases Before 1791 Harold Chesnint and Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr.$ The jury is like rock music. Classical theory frowns; the masses applaud. And in a democracy the felt need of the masses has a claim upon the law.1 There is some evidence that courts of equity in the eighteenth cen- tury and before, and in the early part of the nineteenth century, relied on procedures involving jury trial to determine disputed questions of fact. Because the evidence is modest it suggests rather than demon- strates the validity of the inferences that may be drawn from it. At the same time these inferences may be significant in assessing the consti- tutional position of jury trial in this country. This article seeks to contribute to that assessment and to encourage further research. Broadly, the evidence suggests that at the time of the adoption in 1791 of the Seventh Amendment guarantee of jury trial "in Suits at common law," the practice in the English Court of Chancery was in transition. The court was moving from a rule that disputed fact issues were generally, if not invariably, submitted to juries to one that made such submissions discretionary. The character of this transformation may be inferred from the language of cases decided at different points before and after 1791. In Webb v. Claverdon,2 decided in 1742, the court said: t Member of the New York Bar. $ Professor of Law, Yale University. The research on which this article is based was done chiefly by Mr. -

Equity Jurisdiction in the Federal Courts

University of Pennsylvania Law Review And American Law Register FOUNDED 1852 Published Monthly. November to June, by the Univerity of Pennsylvania Law Schooi, at 34th and Chetnut Street4 Philadelphia. Pa. Vol. 75. FEBRUARY, 1927. No. 4. EQUITY JURISDICTION IN THE FEDERAL COURTS Three lectures, delivered by the writer of this article, in No- vember, 1925, before the Law School of the University of Penn- sylvania,1 treat of the place of common law in, our federal juris- prudence; here, the purpose is to examine the equity side of the same field, to show that, in the national courts, there is a chancery jurisdiction which stands quite free of other juridical powers, and that this is accompanied by a body of uniform rules and rem- edies, not only separate and distinct from those of the various states but entirely independent of, and uncontrolled by, the equity systems there prevailing. In order, however, to understand the genesis, nature and development of federal equity jurisdiction, it is necessary to consider the subject in its relation to the correspond- ing, though dissimilar, growth of equity jurisdiction in the states. From this standpoint, the development of equity powers in the federal courts is highly important,--even more important, per- haps, than the development which has taken place on the common law side of those tribunals; for, as Professor Beale has expressed it, "In a system which has, separately, law and equity, the doc- trines of equity represent the real law." 2 In some of the leading colonies, equity, as a remedial system, either had no existence at all or, where it did exist, suffered from "Published in 74 U. -

Trust and Fiduciary Duty in the Early Common Law

TRUST AND FIDUCIARY DUTY IN THE EARLY COMMON LAW DAVID J. SEIPP∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1011 I. RIGOR OF THE COMMON LAW ........................................................... 1012 II. THE MEDIEVAL USE .......................................................................... 1014 III. ENFORCEMENT OF USES OUTSIDE THE COMMON LAW ..................... 1016 IV. ATTENTION TO USES IN THE COMMON LAW ..................................... 1018 V. COMMON LAW JUDGES AND LAWYERS IN CHANCERY ...................... 1022 VI. FINDING TRUST IN THE EARLY COMMON LAW ................................. 1024 VII. THE ATTACK ON USES ....................................................................... 1028 VIII. FINDING FIDUCIARY DUTIES IN THE EARLY COMMON LAW ............. 1034 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................. 1036 INTRODUCTION Trust is an expectation that others will act in one’s own interest. Trust also has a specialized meaning in Anglo-American law, denoting an arrangement by which land or other property is managed by one party, a trustee, on behalf of another party, a beneficiary.1 Fiduciary duties are duties enforced by law and imposed on persons in certain relationships requiring them to act entirely in the interest of another, a beneficiary, and not in their own interest.2 This Essay is about the role that trust and fiduciary duty played in our legal system five centuries ago and more. -

English Courts of the Present Day W

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 9 | Issue 4 Article 3 1921 English Courts of the Present Day W. Lewis Roberts University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Courts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Roberts, W. Lewis (1921) "English Courts of the Present Day," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 9 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol9/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENGLISH COURTS OF THE PRESENT DAY. W. Lmis ROBERTS Professor of Law, University of Kentucky. The English Judicature Act of 1873 and the supplementary act of 1875 provided for a thorough reorganization of the courts of England and of English judicial procedure. We are all familia with the fact that cases in the common law courts decided before the former Vate are found either in the King's or Queen's Bench reports, in the Exchequer reports or in the Common Plea's relports; but that common law cases decided after that date are found in the reports of the Queen's Bench Division. Few of us, however, ever stop to think that sweeping changes lay behind this departure from the old way of reporting English law cases. Today the superior courts of England consist of the House of Lords, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Judicature, and the Central Criminal Court. -

The Merger of Common-Law and Equity Pleading in Virginia, 41 U

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 1-2006 The eM rger of Common-Law and Equity Pleading in Virginia William Hamilton Bryson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Common Law Commons, Courts Commons, Legal History Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Hamilton Bryson, The Merger of Common-Law and Equity Pleading in Virginia, 41 U. Rich L. Rev. 77 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MERGER OF COMMON-LAW AND EQUITY PLEADING IN VIRGINIA W. Hamilton Bryson * As of January 1, 2006, all civil actions governed by the Rules of Court of the Supreme Court of Virginia are pleaded by a single form of action,1 and the parties can put into one single action all causes of action sounding in common law, equity, and admiralty so far as permitted by the law of joinder of actions.2 The Rules of Court, however, do not apply to causes of action for which the procedure is provided by statute, such as mandamus,3 prohibi- tion,4 quo warranto,5 eminent domain condemnations,6 probate,7 and habeas corpus.8 Substantive rights, whether sounding in common law, equity, probate, divorce, admiralty, or whatever, remain as before. -

A Profusion of Chancery Reform

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2004 A Profusion of Chancery Reform James Oldham Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/595 22 Law & Hist. Rev. 609-614 (2004) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Legal History Commons FORUM: COMMENT A Profusion of Chancery Reform JAMES OLDHAM The refrain that law and equity cannot peaceably cohabit the same court is familiar and persistent. In his 1790 treatise on contracts, Joseph Powell protested that blending law and equity was "subversive of first principles."1 He claimed, "That a right in itself purely legal cannot be the proper sub ject of discussion in a jurisdiction purely equitable, and that a right purely equitable, cannot be the proper subject of a purely legal jurisdiction, are axioms that cannot be denied," adding for good measure: "It is a proposi tion as self-evident as that black is not red, or white black."2 Almost two centuries later, in a provocative 1974 essay called The Death o/Contract, Grant Gilmore asserted that the legal doctrine of consideration in contract law and the equitable doctrine of promissory estoppel were like "matter and anti-matter," and "The one thing that is clear is that these two contra dictory propositions cannot live comfortably together: in the end one must swallow the other Up."3 Gilmore and Powell notwithstanding, law and equity have been able to live together successfully, if occasionally uneasily, for well over a centu ry.