1 Ian Williams* Christopher St German, a Barrister and Writer, Has

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments Through 2016

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 constituteproject.org Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments through 2016 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 Table of contents CHAPTER I: THE STATE AND THE CONSTITUTION . 7 1. The State . 7 2. Constitution is supreme law . 7 CHAPTER II: PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS OF THE INDIVIDUAL . 7 3. Fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual . 7 4. Protection of right to life . 7 5. Protection of right to personal liberty . 8 6. Protection from slavery and forced labour . 10 7. Protection from inhuman treatment . 11 8. Protection from deprivation of property . 11 9. Protection for privacy of home and other property . 14 10. Provisions to secure protection of law . 15 11. Protection of freedom of conscience . 17 12. Protection of freedom of expression . 17 13. Protection of freedom of assembly and association . 18 14. Protection of freedom to establish schools . 18 15. Protection of freedom of movement . 19 16. Protection from discrimination . 20 17. Enforcement of protective provisions . 21 17A. Payment or retiring allowances to Members . 22 18. Derogations from fundamental rights and freedoms under emergency powers . 22 19. Interpretation and savings . 23 CHAPTER III: CITIZENSHIP . 25 20. Persons who became citizens on 12 March 1968 . 25 21. Persons entitled to be registered as citizens . 25 22. Persons born in Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . 26 23. Persons born outside Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . -

Pupillage: What to Expect

PUPILLAGE: WHAT TO EXPECT WHAT IS IT? Pupillage is the Work-based Learning Component of becoming a barrister. It is a 12- 18 month practical training period which follows completion of the Bar Course. It is akin to an apprenticeship, in which you put into practise everything you have learned in your vocational studies whilst under the supervision of an experienced barrister. Almost all pupillages are found in sets of barristers’ chambers. However, there are a handful of pupillages at the ‘employed bar’, which involves being employed and working as a barrister in-house for a company, firm, charity or public agency, such as the Crown Prosecution Service. STRUCTURE Regardless of where you undertake your pupillage, the training is typically broken down into two (sometimes three) distinct parts or ‘sixes’. First Six First six is the informal name given to the first six months of pupillage. It is often referred to as the non-practising stage as you are not yet practising as a barrister in your own right. The majority of your time in first six will be spent attending court and conferences with your pupil supervisor, who will be an experienced barrister from your chambers. In a busy criminal set, you will be in court almost every day (unlike your peers in commercial chambers). In addition to attending court, you will assist your supervisor with preparation for court which may include conducting legal research and drafting documents such as advices, applications or skeleton arguments (a written document provided to the court in advance of a hearing). During first six you will be required to attend a compulsory advocacy training course with your Inn of Court. -

The Inns of Court and the Impact on the Legal Profession in England

SMU Law Review Volume 4 Issue 4 Article 2 1950 The Inns of Court and the Impact on the Legal Profession in England David Maxwell-Fyfe Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation David Maxwell-Fyfe, The Inns of Court and the Impact on the Legal Profession in England, 4 SW L.J. 391 (1950) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol4/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. 19501 THE INNS OF COURT THE INNS OF COURT AND THE IMPACT ON THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN ENGLAND The Rt. Hon. Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, K.C., M.P., London, England A TTHE present day there are many eminent lawyers who have received a part, perhaps the greater part, of their legal grounding at Oxford or Cambridge or other universities, but there was a time when no legal teaching of any consequence, except in Canon and Roman law, was obtainable anywhere outside the Inns of Court. Sir Wm. Blackstone called them "Our Judicial Univer- sity." In them were taught and trained the barristers and the judges who molded and developed the common law and the principles of equity. The Inns were not in earlier times, as they are now, inhabited merely during the daytime by lawyers and students who dispersed in all directions to their homes every night. -

Women and Legal Rights

Chapter I1 "And Justice I Shall Have": Women and Legal Rights New Brunswickfollowed theEnglishlegal so displacing the legal heritage of the other non-British groups in the province: the aboriginal peoples, the reestablished Acadians and other immigrants of European origin, such as the Germans. Like all law, English common law reflected attitudes towards women which were narrow and riddled with misconceptions and prejudices. As those attitudes slowly changed, so did the law.' Common law evolves in two ways: through case law and through statute law. Case law evolves as judges interpret the law; their written decisions form precedents by which to decide future disputes. Statute law, or acts of legislation, change as lawmakers rewrite legislation, often as a result of a change in public opinion. Judges in turn interpret these new statutes, furthering the evolution of the law. Women's legal rights are therefore much dependent on the attitudes of judges, legislators and society. Since early New Brunswick, legal opinion has reflected women's restricted place in society in general and women's highly restricted place in society when mamed. Single women In New Brunswick, as in the rest of Canada, single women have always enjoyed many of the samelegal rights as men. They could always own and manage property in their own name, enter into contracts and own and operate their own businesses. Their civic rights were limited, although less so at times than for married women. However, in spite of their many legal freedoms not sharedby their married sisters, single women were still subject to society's limited views regarding women's capabilities, potential and place. -

UK Immigration, Legal Aid Funding Reform and Caseworkers

Deborah James and Evan Kilick Ethical dilemmas? UK immigration, Legal Aid funding reform and caseworkers Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: James, Deborah and Killick, Evan (2010) Ethical dilemmas? UK immigration, Legal Aid funding reform and caseworkers. Anthropology today, 26 (1). pp. 13-16. DOI: 10.3366/E0001972009000709 © 2009 Deborah James This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/21396/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2011 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Ethical dilemmas? UK immigration, legal aid funding reform and case workers Evan Killick and Deborah James Anthropology Today 26(1):13-15. Anthropologists have an abiding concern with migrants’ transnational movement. Such concern confronts us with some sharp ethical dilemmas.1 Anthropologists have been intensely critical of the forms of law applied to both asylum seekers and potential immigrants, drawing attention to its ‘patchy’ and ‘paradoxical’ character (Andersson 2008). -

“Clean Hands” Doctrine

Announcing the “Clean Hands” Doctrine T. Leigh Anenson, J.D., LL.M, Ph.D.* This Article offers an analysis of the “clean hands” doctrine (unclean hands), a defense that traditionally bars the equitable relief otherwise available in litigation. The doctrine spans every conceivable controversy and effectively eliminates rights. A number of state and federal courts no longer restrict unclean hands to equitable remedies or preserve the substantive version of the defense. It has also been assimilated into statutory law. The defense is additionally reproducing and multiplying into more distinctive doctrines, thus magnifying its impact. Despite its approval in the courts, the equitable defense of unclean hands has been largely disregarded or simply disparaged since the last century. Prior research on unclean hands divided the defense into topical areas of the law. Consistent with this approach, the conclusion reached was that it lacked cohesion and shared properties. This study sees things differently. It offers a common language to help avoid compartmentalization along with a unified framework to provide a more precise way of understanding the defense. Advancing an overarching theory and structure of the defense should better clarify not only when the doctrine should be allowed, but also why it may be applied differently in different circumstances. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1829 I. PHILOSOPHY OF EQUITY AND UNCLEAN HANDS ...................... 1837 * Copyright © 2018 T. Leigh Anenson. Professor of Business Law, University of Maryland; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Business Ethics, Regulation, and Crime; Of Counsel, Reminger Co., L.P.A; [email protected]. Thanks to the participants in the Discussion Group on the Law of Equity at the 2017 Southeastern Association of Law Schools Annual Conference, the 2017 International Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference, and the 2018 Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference. -

William & Mary Law Library

WILLIAM & MARY LAW LIBRARY FIRST DAY SECTION ONE VIRGINIA BOARD OF BAR EXAMINERS Norfclk, Virginia - February 24,2004 WrZte your answer to Questions 1 and 2 in Answer Booklet A - (the WHiTE booklet) 1. While Cameron was visiting her grandmother ("Grandmother") in Roanoke, Virginia, Grandmother showed her three valuable silver cups, nhich had been in their family since the nineteenth century. Each cup was inscribed with the family's last name and bore the respective birth year (1 880, 1885, and 1890) of Cameron's great grandfather and his two brothers. As Cameron admired the cups, Grandmother said, "Cameron, I want you to have the i 890 cup, so take it with you. The 188.5 cup is for your sister: Sofia, in New York. I'm giving it to you to take to her. I intend to give the 1880 cup to your brother, Jackson, who is coming here to see me next week." Cameron thanked Grandmother and took the 1885 and 1890 cups as requested. In a rush to catch her flight at the Roanoke Airport, Cameron inadvertently left the 188.5 silver cup in the back seat pocket of the taxicab she had taken to the airport. Driver, who was an employee of the taxi company, found the silver cup as he was cleaning out the taxi at the end of his shift. Driver told Taxi Owner, who owned the taxi and the taxi company, that he had found the silver cup and that he was going to keep it for himself. Taxi Owner, i/ thinking he recognized the cup, took it from Driver and, over the objection of Driver, ~eturneclit to \.- Grandmother. -

Common Law, Informal and Putative Marriage

COMMON LAW, INFORMAL, AND PUTATIVE MARRIAGE STEPHEN J. NAYLOR The Law Office of Stephen J. Naylor P.L.L.C. 5201 West Freeway, Suite 102 Fort Worth, Texas 76107 (817) 735-1305 Telephone (817) 735-9071 Facsimile [email protected] CHRIS H. NEGEM Law Offices of Chris H. Negem Energy Plaza, Suite 105 8620 North New Braunfels San Antonio, Texas 78217 (210) 226-1200 Telephone (210) 798-2654 Facsimile [email protected] State Bar of Texas 36TH ANNUAL MARRIAGE DISSOLUTION INSTITUTE April 18-19, 2013 Galveston CHAPTER 5 STEPHEN J. NAYLOR Law Office Of Stephen J. Naylor, P.L.L.C. 5201 West Freeway, Suite 102 Fort Worth, TX 76107 Telephone: (817) 735-1305 Facsimile: (817) 735-9071 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: Texas Tech University School of Law J.D. May 1994 Student Senator Officer - Christian Legal Society Officer - Criminal Trial Lawyers Association Recipient, American Jurisprudence Award in Trial Advocacy Recipient, American Jurisprudence Award in Products Liability Texas Tech University B.B.A. in Management, (summa cum laude) 1990 Beta Gamma Sigma Honor Society President's Honor List Dean's Honor List AREAS OF PRACTICE: Board Certified-Family Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES: State Bar Of Texas State Bar Of Texas Family Law Section Tarrant County Bar Association Tarrant County Family Law Bar Association Eldon B. Mahon Inn of Court - Barrister (1999-2002, 2008-2009) Pro Bono Committee, State Bar of Texas Family Law Section 2005 to present Co-Chairman, Pro Bono Committee, State Bar of Texas Family -

The Uk's Leading Immigration Barrister Law Firm

THE UK’S LEADING IMMIGRATION BARRISTER LAW FIRM Tel: +44(0)203 617 9173 Fax: +44(0)203 004 1611 Email: [email protected] www.richmondchambers.com WHY CHOOSE US? WHAT WE DO contents We’ve helped scores of individuals and Our multi-award winning immigration Why choose us? 03 …with Richmond businesses obtain visas for the UK and/or barristers provide expert legal advice and challenge Home Office immigration decisions. representation, directly to individuals and What we do 03 Chambers you get real Our immigration barristers bring years of businesses, in relation to all aspects of UK Investment migration 04 barristers who are at the knowledge and experience to the table. immigration law. top of their profession Family migration 05 and understand the We work hard to understand our clients’ plans We assist individuals with the full range of and objectives. Then we put together the right personal immigration matters, from preparing EEA nationals and family 06 legal system very well. We would highly team, with the right mix of skills, languages and visa applications to enter and remain in the UK, Work visas 07 experience, to help our clients get to where to providing representation at appeals before recommend them. they want to be as easily and cost-effectively the immigration tribunal and higher courts. Short stay visas 08 as possible. Ehab Shouly Study visas 09 Our immigration barristers provide We combine the We’re obsessed with excellence and clear business decision makers with a range of Settlement in the UK 10 expertise and quality communication is vital to what we do. -

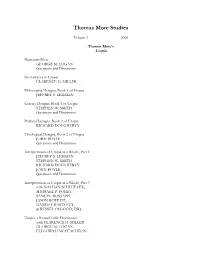

Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) 3 Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) George M

Thomas More Studies Volume 1 2006 Thomas More’s Utopia Humanist More GEORGE M. LOGAN Questions and Discussion No Lawyers in Utopia CLARENCE H. MILLER Philosophic Designs, Book 1 of Utopia JEFFREY S. LEHMAN Literary Designs, Book 1 of Utopia STEPHEN W. SMITH Questions and Discussion Political Designs, Book 2 of Utopia RICHARD DOUGHERTY Theological Designs, Book 2 of Utopia JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 1 JEFFREY S. LEHMAN STEPHEN W. SMITH RICHARD DOUGHERTY JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 2 with NATHAN SCHLUETER, MICHAEL P. FOLEY, SAMUEL BOSTAPH, JASON BOFETTI, GABRIEL BARTLETT, & RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Utopia, a Round Table Discussion with CLARENCE H. MILLER GEORGE M. LOGAN ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON The Development of Thomas More Studies Remarks CLARENCE H. MILLER ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON GEORGE M. LOGAN Interrogating Thomas More Interrogating Thomas More: The Conundrums of Conscience STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Response JOSEPH KOTERSKI, SJ Reply STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Questions and Discussion Papers On “a man for all seasons” CLARENCE H. MILLER Sir Thomas More’s Noble Lie NATHAN SCHLUETER Law in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia as Compared to His Lord Chancellorship RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Variations on a Utopian Diversion: Student Game Projects in the University Classroom MICHAEL P. FOLEY Utopia from an Economist’s Perspective SAMUEL BOSTAPH These are the refereed proceedings from the 2005 Thomas More Studies Conference, held at the University of Dallas, November 4-6, 2005. Intellectual Property Rights: Contributors retain in full the rights to their work. George M. Logan 2 exercises preparing himself for the priesthood.”3 The young man was also extremely interested in literature, especially as conceived by the humanists of the period. -

Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: the Ne Glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607 Daniel R

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers January 1981 Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The nE glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607 Daniel R. Coquillette Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Daniel R. Coquillette. "Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The nE glish Civilian Writers, 1523-1607." Boston University Law Review 61, (1981): 1-89. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 61 NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1981 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW LEGAL IDEOLOGY AND INCORPORATION I: THE ENGLISH CIVILIAN WRITERS, 1523-1607t DANIEL R. COQUILLETTE* "And sure I am that no man can either bring over those bookes of late written (which I have seene) from Rome or Romanists, or read them, and justifie them, or deliver them over to any other with a liking and allowance of the same (as the author's end and desire is they should) but they runne into desperate dangers and downefals .... These bookes have glorious and goodly titles, which promise directions for the conscience, and remedies for the soul, but there is mors in olla: They are like to Apothecaries boxes... whose titles promise remedies, but the boxes themselves containe poyson." Sir Edward Coke "A strange justice that is bounded by a river! Truth on this side of the Pyrenees, error on the other side." 2 Blaise Pascal This Article initiates a three-part series entitled Legal Ideology and In- corporation. -

Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System George Jarvis Thompson

Cornell Law Review Volume 17 Article 1 Issue 2 February 1932 Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System George Jarvis Thompson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation George Jarvis Thompson, Development of the Anglo-American Judicial System, 17 Cornell L. Rev. 203 (1932) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol17/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORNELL LAW QUARTERLY VOLUME XVII FEBRUARY, 1932 NUMBER 2 THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANGLO-AMERICAN JIUDICIAL SYSTEM* GEORGE JARVIS THOMPSONt PART I HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH COURTS TO THE JUDICATURE ACTS b. The PrerogativeCourts 6"' In post-Conquest England, as in most primitive societies, the king as the fountain of justice and supreme administrator of the laws decided each case before him according to his royal will, exercising a prerogative or extraordinary jurisdiction much like the oriental justice of the Arabian Nights tales1 70 With respect to the conquered English, the king's justice in this period was always extraordinary. *Copyright, 1932, by George Jarvis Thompson. This article is the second installment of Part I of a historical survey of the Anglo-American judicial system. The first installment appeared in the December, 1931, issue of the CORNELL LAW QUARTERLY. It is expected that the succeeding installments of Part I will appear in subsequent issues of this volume.