Violence, Power, and Human Sacrifice in Ancient Egypt A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ug Abuse and Dependence

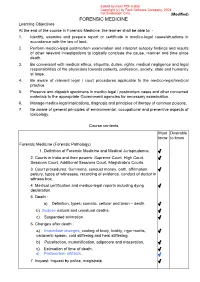

Edited by Foxit PDF Editor Copyright (c) by Foxit Software Company, 2004 For Evaluation Only. (Modified) FORENSIC MEDICINE Learning Objectives At the end of the course in Forensic Medicine, the learner shall be able to: - 1. Identify, examine and prepare report or certificate in medico-legal cases/situations in accordance with the law of land. 2. Perform medico-legal postmortem examination and interpret autopsy findings and results of other relevant investigations to logically conclude the cause, manner and time since death. 3. Be conversant with medical ethics, etiquette, duties, rights, medical negligence and legal responsibilities of the physicians towards patients, profession, society, state and humanity at large. 4. Be aware of relevant legal / court procedures applicable to the medico-legal/medical practice. 5. Preserve and dispatch specimens in medico-legal / postmortem cases and other concerned materials to the appropriate Government agencies for necessary examination. 6. Manage medico-legal implications, diagnosis and principles of therapy of common poisons. 7. Be aware of general principles of environmental, occupational and preventive aspects of toxicology. Course contents Must Desirable know to know Forensic Medicine (Forensic Pathology) 1. Definition of Forensic Medicine and Medical Jurisprudence. √ 2. Courts in India and their powers: Supreme Court, High Court, √ Sessions Court, Additional Sessions Court, Magistrate’s Courts. 3. Court procedures: Summons, conduct money, oath, affirmation, √ perjury, types of witnesses, recording of evidence, conduct of doctor in witness box, 4. Medical certification and medico-legal reports including dying √ declaration. 5. Death : a) Definition, types; somatic, cellular and brain – death. √ b) Sudden natural and unnatural deaths. √ c) Suspended animation. √ 6. -

DOA Stories and Questions

Name:_________________ Hour:_______ Dead On Arrival Articles Getting Rid of the Body !Criminals don"t like to leave behind evidence, although they usually do. In a murder, the primary bit of evidence is obviously the body. Sometimes a murderer attempts to completely destroy the body of a victim, reasoning that no body means no conviction. Not true -- convictions have been obtained even when no body is found. Regardless, destroying a body is no easy task. Fire seems to be the favorite tool of murderers looking to cover their tracks, but its almost never successful. Short of a crematorium, creating a fire that burns hot enough and long enough to destroy a human corpse is nearly impossible. !Another favorite is quicklime, which murderers often have seen used in the movies. Knowing the chemistry behind it might make them think twice about this one. Quicklime is calcium oxide. When it contacts water, as it often does in burial sites, it reacts with the water to make calcium hydroxide, also known as slaked lime. This corrosive material may damage the surface of the corpse, but the heat produced from its activity kills many of the putrefying bacteria and dehydrates the body, thereby preventing decay and promoting mummification. Thus, the use of quicklime actually may help preserve the body. !Acids also are commonly used by ill-informed criminals hoping to dissolve the body, which is not only difficult but extremely hazardous. Acids that are powerful enough to dissolve a body exist, but they require a great deal of time to complete the task. -

Forensic Medicine and Toxicology

FORENSIC MEDICINE AND TOXICOLOGY CURRICULUM OF SYLLABUS UNDER THE NEW REGULATIONS FOR THE MBBS. COURSES OF STUDIES EFFECTIVE FROM THE SESSION: 2017-18 . 3RD SEMESTER: 1.INTRODUCTION (1hr) a. Definitions: forensic medicine, state medicine, legal medicine, medical jurisprudence, medical ethics, medical etiquette b. Various branches of forensic science. c. History and evolution of forensic medicine from ancient period to modern period 2.LEGAL PROCEDURE (2hr) a. Definition: bill, act, code, court, law, statutory law b. Major codes and acts: Indian Penal Code (IPC), Criminal Procedure Code (Cr.PC), Indian Evidence Act c. Different Courts of Law, their structure and functions: Supreme Court, High Court, Sessions Court, Judicial Magistrate Courts d. Offences: cognizable/non-cognizable, bailable/non-bailable, warrant case, summon case e. Different types of punishments authorized by law f. Inquest: definition, types and procedure of different inquests [police inquest, magistrate inquest (executive and judicial magistrate inquest), coroner’s inquest, medical examiner’s system] g. Summon: definition, types, salient features h. Conduct money i. Medical evidence: definition, types (documentary and oral), documentary evidence (defn, types of medical documentary evidences), special emphasis on ‘how to record dying declaration’, oral evidence (defn, exception to oral evidence), direct evidence, indirect evidence (circumstantial and hearsay) j. Chain of custody k. Witness: definition, types, hostile witness and perjury l. Procedure of recording of evidence in Court of law: starting from receiving a summon, oath taking, examination in chief, cross examination, re-examination, question by the Judge, checking the written form of oral evidence by the doctor, Court attendance certificate m. Conduct and duties of a doctor in witness box n. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

Lawyer's Guide to Forensic Medicine

LAWYER’S GUIDE TO FORENSIC MEDICINE CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney LAWYER’S GUIDE TO FORENSIC MEDICINE Second Edition Bernard Knight, CBE, MD, DSc (Hon), LLD (Hon), BCh, MRCP, FRCPath, Dip Med Jur Barrister of Gray’s Inn Emeritus Professor of Forensic Pathology, University of Wales College of Medicine CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney Published in Great Britain 1998 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom. Telephone: +44 (0) 171 278 8000 Facsimile: +44 (0) 171 278 8080 E-mail: [email protected] Visit our Home Page on http://www.cavendishpublishing.com First published by William Heinemann Medical Books 1982 © Knight, Bernard 1998 First edition 1982 Second edition 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. Knight, Bernard Lawyer’s Guide to Forensic Medicine – 2nd edn 1. Medical jurisprudence I. Title 614.1 ISBN 1 85941 159 2 Printed and bound in Great Britain PREFACE The 16 years that have elapsed since the first edition of this book have seen many changes which require significant updating of the text. Some entries have been deleted and others added, to reflect the changing priorities in the interface between medicine and the law. -

Cranial Suture Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Insights and Advances

biomolecules Review Cranial Suture Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Insights and Advances Bo Li 1, Yigan Wang 1, Yi Fan 2, Takehito Ouchi 3 , Zhihe Zhao 1,* and Longjiang Li 4,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Orthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China; [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (Y.W.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Cariology and Endodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Physiology, Tokyo Dental College, Tokyo 1010061, Japan; [email protected] 4 State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Head and Neck Oncology, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (L.L.) Abstract: The cranial bones constitute the protective structures of the skull, which surround and protect the brain. Due to the limited repair capacity, the reconstruction and regeneration of skull defects are considered as an unmet clinical need and challenge. Previously, it has been proposed that the periosteum and dura mater provide reparative progenitors for cranial bones homeostasis and injury repair. In addition, it has also been speculated that the cranial mesenchymal stem cells reside in the perivascular niche of the diploe, namely, the soft spongy cancellous bone between the interior and exterior layers of cortical bone of the skull, which resembles the skeletal stem cells’ distribution pattern of the long bone within the bone marrow. -

Hijikata Tatsumi's Sabotage of Movement and the Desire to Kill The

Death and Desire in Contemporary Japan Representing, Practicing, Performing edited by Andrea De Antoni and Massimo Raveri Hijikata Tatsumi’s Sabotage of Movement and the Desire to Kill the Ideology of Death Katja Centonze (Universität Trier, Deutschland; Waseda University, Japan) Abstract Death and desire appear as essential characteristics in Hijikata Tatsumi’s butō, which brings the paradox of life and death, of stillness and movement into play. Hijikata places these con- tradictions at the roots of dance itself. This analysis points out several aspects displayed in butō’s death aesthetics and performing processes, which catch the tension between being dead and/or alive, between presence and absence. It is shown how the physical states of biological death are enacted, and demonstrated that in Hijikata’s nonhuman theatre of eroticism death stands out as an object aligned with the other objects on stage including the performer’s carnal body (nikutai). The discussion focuses on Hijikata’s radical investigation of corporeality, which puts under critique not only the nikutai, but even the corpse (shitai), revealing the cultural narratives they are subjected to. Summary 1 Deadly Erotic Labyrinth. – 2 Death Aesthetics for a Criminal and Erotic Dance. – 3 Rigor Mortis and Immobility. – 4 Shibusawa Tatsuhiko. Performance as Sacrifice and Experience. – 5 Pallor Mortis and shironuri. – 6 Shitai and suijakutai. The Dead are Dancing. – 7 The Reiteration of Death and the miira. – 8 The shitai under Critique. Death and the nikutai as Object. – 9 Against the Ideology of Death. Keywords Hijikata Tatsumi. Butō. Death. Eroticism. Corporeality. Acéphale. Anti-Dance. Body and Object. Corpse. Shibusawa Tatsuhiko. -

Modelling Suture Ossification: a View from the Cranial Capsule

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-1992 Modelling Suture Ossification: A View from the Cranial Capsule Hugh Bryson Matternes University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Matternes, Hugh Bryson, "Modelling Suture Ossification: A View from the Cranial Capsule. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Hugh Bryson Matternes entitled "Modelling Suture Ossification: A View from the Cranial Capsule." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Richard L. Jantz, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Lyle W. Konigsberg, William M. Bass Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: -

Cranial Sutures & Funny Shaped Heads: Radiological Diagnosis

Objectives • The objectives of this presentation are to: – Review the imaging features of normal cranial sutures – Identify the characteristics of abnormal skull shape on imaging – Review the characteristics of the most common non- syndromic and syndromic causes of craniosynostosis Anatomical Review Anatomical Review • The bony plates of the skull communicate at the cranial sutures • The anterior fontanelle occurs where the coronal & metopic sutures meet • The posterior fontanelle occurs where the sagittal & lambdoid sutures meet Anatomical Review • The main cranial sutures & fontanelles include: Metopic Suture Anterior Fontanelle Coronal Sutures Squamosal Sutures Posterior Fontanelle Sagittal Suture Lambdoid Sutures Anatomical Review • Growth of the skull occurs perpendicular to the cranial suture • This is controlled by a complex signalling system including: – Ephrins (mark the suture boundary) – Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR) – Transcription factor TWIST Anatomical Review • The cranial sutures are important for rapid skull growth in-utero & infancy • The cranial sutures can usually be visualised on imaging into late adulthood Normal Radiological Appearances Normal Radiological Appearances • The cranial sutures can be visualised on plain radiographs • Standard views include: – PA – Lateral – Townes PA Skull radiograph Sagittal Suture Left Coronal Suture Right CoronalRight lambdoidSutureSuture Metopic Suture Left lambdoid Suture Townes View Sagittal Suture Left Coronal Suture Right Coronal Suture Right Lambdoid Suture Left -

A Heads up on Craniosynostosis

Volume 1, Issue 1 A HEADS UP ON CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS Andrew Reisner, M.D., William R. Boydston, M.D., Ph.D., Barun Brahma, M.D., Joshua Chern, M.D., Ph.D., David Wrubel, M.D. Craniosynostosis, an early closure of the growth plates of the skull, results in a skull deformity and may result in neurologic compromise. Craniosynostosis is surprisingly common, occurring in one in 2,100 children. It may occur as an isolated abnormality, as a part of a syndrome or secondary to a systemic disorder. Typically, premature closure of a suture results in a characteristic cranial deformity easily recognized by a trained observer. it is usually the misshapen head that brings the child to receive medical attention and mandates treatment. This issue of Neuro Update will present the diagnostic features of the common types of craniosynostosis to facilitate recognition by the primary care provider. The distinguishing features of other conditions commonly confused with craniosynostosis, such as plagiocephaly, benign subdural hygromas of infancy and microcephaly, will be discussed. Treatment options for craniosynostosis will be reserved for a later issue of Neuro Update. Types of Craniosynostosis Sagittal synostosis The sagittal suture runs from the anterior to the posterior fontanella (Figure 1). Like the other sutures, it allows the cranial bones to overlap during birth, facilitating delivery. Subsequently, this suture is the separation between the parietal bones, allowing lateral growth of the midportion of the skull. Early closure of the sagittal suture restricts lateral growth and creates a head that is narrow from ear to ear. However, a single suture synostosis causes deformity of the entire calvarium. -

Buried but Alive?

Buried but Alive? Interpreting Post-depositional Bone Movement, Anxieties over Death and Premature Burial BY SIAN ANTHONY Abstract The young, beautiful and wealthy widow Giertrud Birgitte Bodenhoff was buried in Assistens cemetery, Copenhagen on 23 July 1798 but was she dead? Family stories claimed she had been buried alive but was found by grave-robbers who then killed her to conceal their crime. Her skeleton was exhumed in 1953 and the unexpected position of it within the coffin was used to confirm the stories, which echo many similar narratives that betray anxieties over death and premature burial. With advances in archaeological methods and forensic taphonomy, this conclusion requires reinterpretation. The burial environment is not static and the body and later the skeleton can move while undergoing the de- cay process. The position of the skeleton in burials excavated in the same cemetery from 2009–11 is used to review the Bodenhoff story. How does decomposition move the bones within a well-preserved coffin? Can some typical movements of bones in coffins be identified in Assistens to advance greater understanding of what happens underground in the coffin? Introduction Gothic literature and popular culture are full collected as evidence that premature burial of premature burials, but the fear of being was a common phenomenon (e.g. Tebb & buried alive is also a long-held fascination Vollum 1896). The behaviour of people, as in the western world, with stories attested told in the stories, suggests a malleable sense from the Classical period onwards. There of death where it is a reversible and porous was a particular peak of interest in the 18th state (Ariès 1981, 609) in contrast to a finite and 19th centuries (Bondesen 2001, 77 medical state. -

The Sima De Los Huesos Crania: Analysis of the Cranial Breakage Patterns

Journal of Archaeological Science 72 (2016) 25e43 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas The Sima de los Huesos Crania: Analysis of the cranial breakage patterns * Nohemi Sala a, b, c, , Ana Pantoja-Perez c, a, d, Juan Luis Arsuaga c, d, Adrian Pablos e, f, a, c, Ignacio Martínez a, c a Area de Antropología Física, Departamento de Ciencias de la Vida, Universidad de Alcala, Madrid, Spain € b Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte und Archaologie€ des Mittelalters Abteilung für Altere Urgeschichte und Quartar€ okologie,€ Eberhard-Karls Universitat€ Tübingen, Schloss Hohentübingen, 72070 Tübingen, Germany c Centro Mixto UCM-ISCIII de Evolucion y Comportamiento Humanos, Madrid, Spain d Departamento de Paleontología, Facultad Ciencias Geologicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain e Centro Nacional de Investigacion sobre Evolucion Humana-CENIEH, Burgos, Spain f Paleoanthropology, Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment, Eberhard Karls Universitat€ Tübingen, Germany article info abstract Article history: The Sima de los Huesos (SH) site has provided the largest collection of hominin crania in the fossil record, Received 29 March 2016 offering an unprecedented opportunity to perform a complete Forensic-Taphonomic study on a popu- Received in revised form lation from the Middle Pleistocene. The fractures found in seventeen crania from SH display a post- 1 June 2016 mortem fracturation pattern, which occurred in the dry bone stage and is compatible with collective Accepted 3 June 2016 burial assemblages. Nevertheless, in addition to the postmortem fractures, eight crania also display some Available online 14 June 2016 typical perimortem traumas. By using CT images we analyzed these fractures in detail.