Hezbollah Psychological Warfare Against Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Three Perspectives on the Second Intifada

Three Perspectives on the Second Intifada Perspective I: “What Caused the Current Wave of Palestinian Terrorism?” Source: Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs; http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFA-Archive/2003/Pages/Israel- %20the%20Conflict%20and%20Peace-%20Answers%20to%20Frequen.aspx#terror The wave of terrorism that began in September 2000 is the direct result of a strategic Palestinian decision to use violence - rather than negotiation - as the primary means to advance their agenda. Despite Palestinian claims to the contrary, Israel's so-called "occupation" of the territories is not the true cause of the terrorism, as negotiations could have peacefully resolved all aspects of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict well before the violence started. When the wave of violence and terrorism began in September 2000, the Palestinians originally claimed that it was a spontaneous reaction to the visit of then-opposition leader Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount. However, later statements by Palestinian leaders in the Arab-language media contradicted this assertion. Neither did the report issued by the Mitchell Committee, composed of American and European leaders, give support to the earlier Palestinian claim. Consequently, Palestinian spokespersons changed their tactics and instead began to assert that the violence was a response to Israel's "occupation" of the West Bank and Gaza. This claim ignores events both before and after 1967 (when Israel came into control of the territories during a war of self-defense) that prove that the "occupation" is not the true cause of Palestinian terrorism. Not only did Palestinian terrorism precede Israel's presence in the West Bank and Gaza; it has often hit brutally at those moments, as in 1994-1996, when the peace process was making the greatest progress. -

THE CHALLENGE of GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications

BROOKINGS 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20036-2103 www.brookings.edu ANALYSIS PAPER Number 23, July 2011 THE CHALLENGE OF GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications Daniel Byman Gad Goldstein ANALYSIS PAPER Number 23, July 2011 THE CHALLENGE OF GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications Daniel Byman Gad Goldstein The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2011 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu Table of Contents Executive Summary . iv Acknowledgements . ix The Authors . x Introduction . 1 The Nature of the Challenge in Gaza . 3 Factors Beyond Gaza to Consider . 18 Policy Options . 24 THE CHALLENGE OF GAZA: Policy Options and Broader Implications The Saban Center at BRooKings iii Executive Summary lthough both the United States and Israel Hamas draws on many resources to stay in power . devote tremendous attention to the Middle Most notably, Hamas has long exploited its infra- East peace process, the Gaza Strip and its structure of mosques, social services, and communi- HamasA government have continued to vex Ameri- ty organizations to raise money and attract recruits . -

The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada

The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada Yoram Schweitzer The decades-long Israeli-Palestinian conflict has seen several rounds of violence and has claimed many casualties on both sides. The second 1 intifada occupies a particularly painful place, especially for the Jewish population, which suffered an unprecedented high casualty toll – dead and injured – in a relatively short period of time. As part of the violence perpetrated by the Palestinians during the second intifada, suicide bombings played a particularly prominent role and served as the primary effective weapon in the hands of the planners. Since the outbreak of the second intifada in late September 2000 until today, there have been a total of 146 suicide attacks, and more than 389 2 suicide attacks have been foiled. Although the relative representation in the total number of hostile activities waged by Palestinian organizations was not high, suicide attacks were without a doubt the most significant component in the death and destruction they sowed. In the decade since September 2000, 516 of the 1178 deaths (43.8 percent) were caused by suicide attacks. In addition to the attacks on Israeli civilians, which also resulted in thousands of physical and emotional casualties, suicide bombings helped the Palestinian organizations instill fear among the Israeli public and create a sense – even if temporary – of danger on the streets, on public transportation, and at places of entertainment. This essay presents a short description and analysis of the rise and fall of suicide terrorism in the decade since the second intifada erupted. It then presents the Israeli and Palestinian perspectives regarding their relative success in attaining their respective goals. -

The IDF in the Second Intifada

Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade |Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | Shiri Tal-Landman המכון למחקרי ביטחון לאומי THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURcITY STUDIES INCORPORATING THE JAFFEE bd CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 CONteNts Abstracts | 3 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | 7 Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | 27 Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | 39 Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | 49 Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | 63 Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | 71 Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | 85 Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | 101 Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade | 123 Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | 133 Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | 141 Shiri Tal-Landman The purpose of Strategic Assessment is to stimulate and Strategic enrich the public debate on issues that are, or should be, ASSESSMENT on Israel’s national security agenda. -

Pdf | 408.55 Kb

Middle East Report Online: Another War Zone: Social Media in the Isra... http://www.merip.org/mero/interventions/steinINT.html Another War Zone: Social Media in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Adi Kuntsman and Rebecca L. Stein September 2010 Search MERIP (Adi Kuntsman is Leverhulme Research Fellow at the Research Institute for Cosmopolitan Cultures of the University of Manchester. Rebecca L. Stein is associate professor of cultural anthropology at Duke University.) Middle East Report Online Subject Index In late May Afghanistan and 2010, the Pakistan convoy Algeria known as Arab and Muslim Subscribe Online to Middle East Report the Americans Freedom Arabian Peninsula Flotilla Egypt met off Elections Order a subscription and of Europe and the back issues to the award- Middle East winning magazine Middle Cyprus East Report. and From the Editors Horn of Africa Click here for the order headed page. south, Human Rights carrying International Law/International SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Justice Interventions Primer on Palestine, Iran Israel and the Arab-Israeli Conflict Iraq Israeli ship warns Freedom Flotilla not to proceed to Gaza. Still from Click here (PDF) Israel Israeli navy video distributed on YouTube. [Click here for HTML Israel and version] humanitarian aid and hundreds of international activists who aimed to break Israel’s Lebanon/Syria Jordan blockade of the Gaza Strip. The organizers used social media extensively: tweeting updates from the boats; webcasting live with cameras uplinked to the Internet and a Kuwait satellite, enabling simultaneous rebroadcasting; employing Facebook, Flickr, YouTube Kurds and and other social networking websites to allow interested parties to see and hear them in Kurdistan real time; and using Google Maps to chart their location at sea. -

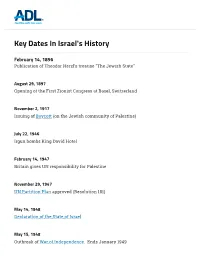

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution -

A Decade Since the Outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada: a Strategic the IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland the Rise and Fall

Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade |Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | Shiri Tal-Landman המכון למחקרי ביטחון לאומי THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURcITY STUDIES INCORPORATING THE JAFFEE bd CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 13 | No. 3 | October 2010 CONteNts Abstracts | 3 A Decade since the Outbreak of the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Strategic Overview | 7 Michael Milstein The IDF in the Second Intifada | 27 Giora Eiland The Rise and Fall of Suicide Bombings in the Second Intifada | 39 Yoram Schweitzer The Political Process in the Entangled Gordian Knot | 49 Anat Kurz The End of the Second Intifada? | 63 Jonathan Schachter The Second Intifada and Israeli Public Opinion | 71 Yehuda Ben Meir and Olena Bagno-Moldavsky The Disengagement Plan: Vision and Reality | 85 Zaki Shalom Israel’s Coping with the al-Aqsa Intifada: A Critical Review | 101 Ephraim Lavie 2000-2010: An Influential Decade | 123 Oded Eran Resuming the Multilateral Track in a Comprehensive Peace Process | 133 Shlomo Brom and Jeffrey Christiansen The Core Issues of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict: The Fifth Element | 141 Shiri Tal-Landman The purpose of Strategic Assessment is to stimulate and Strategic enrich the public debate on issues that are, or should be, ASSESSMENT on Israel’s national security agenda. -

Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict∗

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/12/48 25 September 2009 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Twelfth session Agenda item 7 HUMAN RIGHTS IN PALESTINE AND OTHER OCCUPIED ARAB TERRITORIES Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict∗ ∗ Late submission. GE.09-15866 A/HRC/12/48 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Acronyms and abbreviations .......................................................................................... 11 Executive summary .............................................................................. 1-130 13 PART ONE: METHODOLOGY, CONTEXT AND APPLICABLE LAW INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 131-150 37 I. METHODOLOGY ............................................................... 151-175 41 A. Mandate and terms of reference ................................. 151-155 41 B. Methods of work ......................................................... 156-167 42 C. Assessment of information ......................................... 168-172 44 D. Consultation with the parties ...................................... 173-175 45 II. CONTEXT............................................................................. 176-222 46 A. Historical context......................................................... 177-197 46 B. Overview of Israel’s pattern of policies and conduct relevant to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, and links between the situation in Gaza and in the West Bank...................................... 198-209 -

From Cast Lead to Protective Edge: Lessons from Israel's Wars in Gaza

From Cast Lead to Protective Edge Lessons from Israel’s Wars in Gaza Raphael S. Cohen, David E. Johnson, David E. Thaler, Brenna Allen, Elizabeth M. Bartels, James Cahill, Shira Efron C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1888 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9787-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photos (clockwise): Nir Elias/Reuters; Amir Cohen/Reuters; Abu Mustafa/Reuters; Tsafrir Abayov/AP Photo Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report examines the Israel Defense Forces operations in Gaza from the end of Operation Cast Lead in 2009 through Operation Pillar of Defense in 2012 to Operation Protective Edge in 2014. -

What Happened on the Mavi Marmara? an Analysis of the Turkel Commission Report

TÜRKİYE ORTADOĞU ÇALIŞMALARI DERGİSİ Turkish Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Cilt: 1, Sayı: 2, 2014, ss.31-53 What Happened on the Mavi Marmara? An Analysis of the Turkel Commission Report Norman Finkelstein* Abstract On 31 May 2010, Israeli commandos killed nine Turkish citizens aboard the Mavi Marmara, the flagship vessel of a humanitarian flotilla headed for besieged Gaza. The Israeli attack evoked international outrage, which caused Israel to appoint an official commission of inquiry chaired by former Israeli Supreme Court Judge Jacob Turkel. In January 2011, the Turkel Commission released a 300 page report that allegedly established what happened in the course of the Israeli assault. In fact, and unsurprisingly, the report was a grotesque whitewash of Israeli acti- ons. Nonetheless this mendacious report effectively shielded Israel from further international scrutiny. A panel of inquiry created by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to resolve differences between Turkey and Israel over the Mavi Marmara killings “fully associated itself” - in the bitter words of the Turkish representative on the panel - with the the Turkel report’s findings. To date, no independent rese- archer has exposed in detail the dishonesty and fraud of the Turkel report. The purpose of my article is to fill this gap. Keywords: Mavi Marmara, Israel, Turkey, International Law, Turkel Report * Assoc. Prof., Sakarya University, Center for Middle Eastern Studies - [email protected] 31 TURKISH JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES Türkiye Ortadoğu Çalışmaları Dergisi Vol: 1, No: 2, 2014, ss.31-53 Mavi Marmara’da Ne Oldu? Turkel Komisyonu Raporunun Analizi Norman Finkelstein* Özet 31 Mayıs 2010 tarihinde kuşatma altındaki Gazze’ye yardım götürmekte olan Mavi Marmara gemisinde bulunan 9 Türk vatandaşı İsrailli komandolar tarafın- dan öldürüldü. -

Twenty-Seven Months -- Intifada, Closures

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen World Bank Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Twenty-Seven Months - Intifada, Closures and Twenty-Seven Months - Intifada, Closures and Palestinian Economic Crisis Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized An Assessment Palestinian Economic Crisis Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized An Assessment Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized May 2003 World Bank, May 2003 Cover-final.prn J:\World Bank\27months\Cover\Cover-final.cdr 20 June, 2003 02:06:51 PM Twenty-Seven Months - Intifada, Closures and Palestinian Economic Crisis An Assessment The World Bank May 2003 All rights reserved ©2003 The World Bank West Bank and Gaza Office P.O.Box 54842, Jerusalem ii Contents PREFACE.................................................................................................................................. VII ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS...................................................................................IX SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................XI THE PALESTINIAN ECONOMY IN 2002.........................................................................................XI Dramatic Decline, Signs of Stabilization............................................................................... xi Averting Economic Collapse................................................................................................xiii