Expanding Food Justice: Gender, Race and Hunger in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 1, 2017 Time: 9:30 A.M

City Planning Division Anita MacLeod Committee of Adjustment Manager & Deputy Secretary Treasurer City Hall 100 Queen Street West Toronto ON M5H 2N2 Tel: 416-392-7565 Fax: 416-392-0580 COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT AGENDA TORONTO EAST YORK PANEL Hearing Date: March 1, 2017 Time: 9:30 a.m. Location: Committee Room - Toronto City Hall - 100 Queen Street West 1. OPENING REMARKS Declarations of Interest Confirmation of Minutes from Previous Hearing Closed & Deferred Files 2. DEPUTATION ITEMS The following applications will be heard at 9:30 a.m. or shortly thereafter: File Number Property Community (Ward) 1. A1114/16TEY 76 ROSEHEATH AVE Beaches-East York (32) 2. A1115/16TEY 44 MCGILL ST Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 3. A1116/16TEY 2154 QUEEN ST E Beaches-East York (32) 4. A1117/16TEY 159 HUDSON DR Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 5. A1119/16TEY 34 BELLWOODS AVE Trinity-Spadina (19) 6. A1120/16TEY 1090 - 1092 Toronto-Danforth (29) DANFORTH AVE 7. A1122/16TEY 354 MAIN ST Beaches-East York (31) 8. A1123/16TEY 554 DUFFERIN ST Davenport (18) 9. A1124/16TEY 173 TORRENS AVE Toronto-Danforth (29) 10. A1125/16TEY 97 LESMOUNT AVE Toronto-Danforth (29) 11. A1126/16TEY 97 A GRANBY ST Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 12. A1127/16TEY 220 ROBERT ST Trinity-Spadina (20) 13. A1128/16TEY 65 HAMMERSMITH Beaches-East York (32) AVE 14. A1174/16TEY 31 SUMMERHILL Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) AVE 15. A1276/16TEY 591 DUNDAS ST E (51 Toronto Centre-Rosedale (28) WYATT AVE) 1 The following applications will be heard at 1:30 p.m. or shortly thereafter: File Number Property Community (Ward) 16. -

Women's Suffrage in Ontario the Beginning of Women’S Suffrage Movements

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY an educational resource OF ONTARIO MESSAGE TO TEACHERS This educational resource was developed to compliment the documentary Women Should Vote: A Short History of how Women Won the Franchise in Ontario (www.ola.org/en/visit-learn/ about-ontarios-parliament/womens-suffrage-ontario), A NOTE ON LANGUAGE which tells the story of the struggle for women’s Some historical terms used in this resource are suffrage in Ontario at the turn of the 20th century. no longer in common use. First Nations peoples in Canada were initially called “Indians” by colonial It invites students to deepen their understanding of Europeans. This term is no longer used, though gender equality and democracy through examining and “Status Indian” is still a legal definition and is analyzing the suffrage movement, and facilitates mentioned throughout this guide. “Status Indian” engaging discussions and activities. Students will does not include all Indigenous peoples – for examine issues of identity, equity, activism and example, Métis and Inuit are excluded (see the justice in historical and contemporary contexts. Glossary on Page 22 for more information). CONTENTS The Suffrage Movement in Running the Good Race ............. 9 Glossary ......................... 22 Ontario: Votes for Women ............ 2 Indigenous Suffrage ............... 11 Activities The Beginning of Women’s Clues from the Archives Suffrage Movements ................ 3 Final Reflections ..................13 (Designed for Grades 8-12) .......23 Should I Support the Vote? The Long Road Timeline of Women’s Suffrage (Designed for Grades 4-7) ........24 to Women’s Suffrage ................ 4 in Ontario and Canada ............. 14 Our Rights Today ................25 A New Century ..................... 5 Feature Figures Appendix A ...................... -

The Woman Candidate for the Ontario Legislative Assembly, 1919-1929 Frederick Brent Scollie

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 11:37 Ontario History The Woman Candidate for the Ontario Legislative Assembly, 1919-1929 Frederick Brent Scollie Volume 104, numéro 2, fall 2012 Résumé de l'article L’histoire brosse un tableau sombre du manque de succès électoral des femmes URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065435ar ontariennes après 1919, l’année où elles ont obtenu le droit d’être élues à la DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1065435ar législature et aux conseils municipaux. Nous examinons de près treize des 21 femmes qui ont posé leur candidature à l’Assemblée législative de l’Ontario Aller au sommaire du numéro avant 1943, notamment les douze qui furent candidates entre 1919-1929, toutes vaincues, le succès politique de quelques-unes de leurs prédécesseurs élues à des commissions scolaires dès 1892, et l’expérience de ces femmes avec les Éditeur(s) partis politiques. Cela nous permet de vérifier les thèses et explications offertes par la politologue Sylvia Bashevkin et la sociologue Thelma McCormack sur le The Ontario Historical Society comportement politique des femmes au Canada anglais. ISSN 0030-2953 (imprimé) 2371-4654 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Scollie, F. B. (2012). The Woman Candidate for the Ontario Legislative Assembly, 1919-1929. Ontario History, 104(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065435ar Copyright © The Ontario Historical Society, 2012 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. • • " •.. •• . " "" ~ •• City Clerk's Office Secretariat Christine Archibald Toronto and East York Community Council 1 City Hall, 12 h Floor, West 100 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 OOlE~[ij UOOle©!E~W!EllD IN THE MATTER OF THE ONTARIO HERITAGE ACT R.S.O. 1990 CB APTER 0.18 AND 2 2 --08- 2006 53 TURNER ROAD CITY OF TORONTO, PROVINCE OF ONTARIO ----·----------- NOTICE OF INTENTION TO DESIGNATE • Ontario Heritage Trust 53 Turner Road 10 Adelaide Street East Toronto, Ontario Toronto, ,Ontario M6G3H7 MSC 1J3 Take notice that Toronto City Council intends to designate the lands and buildings known municipally as 53 Turner Road (St. Paul's, Ward 21) under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act. Reasons for Designation: Description The property at 53 Turner Road is worthy of designation under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, and meets the criteria for municipal designation prescribed by the Province of Ontario under the three categories of design or physical value, historical or associative value, and contextual value. Located on the southeast comer of Turner Road and Tyrrell Avenue, the detached house forn1 building was constructed for businessman John Agnew in 1926. Statement of Cultural Heritage Value The cultural heritage value of the John Agnew House is related to its design or physical value as a 1~-storey cottage that is a representative example of Period Revival styling reflecting a high degree of craftsmanship, including interior features. -

MAKING the SCENE: Yorkville and Hip Toronto, 1960-1970 by Stuart

MAKING THE SCENE: Yorkville and Hip Toronto, 1960-1970 by Stuart Robert Henderson A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada October, 2007 Copyright © Stuart Robert Henderson, 2007 Abstract For a short period during the 1960s Toronto’s Yorkville district was found at the centre of Canada’s youthful bohemian scene. Students, artists, hippies, greasers, bikers, and “weekenders” congregated in and around the district, enjoying the live music and theatre in its many coffee houses, its low-rent housing in overcrowded Victorian walk- ups, and its perceived saturation with anti-establishmentarian energy. For a period of roughly ten years, Yorkville served as a crossroads for Torontonian (and even English Canadian) youth, as a venue for experimentation with alternative lifestyles and beliefs, and an apparent refuge from the dominant culture and the stifling expectations it had placed upon them. Indeed, by 1964 every young Torontonian (and many young Canadians) likely knew that social rebellion and Yorkville went together as fingers interlaced. Making the Scene unpacks the complicated history of this fraught community, examining the various meanings represented by this alternative scene in an anxious 1960s. Throughout, this dissertation emphasizes the relationship between power, authenticity and identity on the figurative stage for identity performance that was Yorkville. ii Acknowledgements Making the Scene is successful by large measure as a result of the collaborative efforts of my supervisors Karen Dubinsky and Ian McKay, whose respective guidance and collective wisdom has saved me from myself on more than one occasion. -

St. Clair West in Pictures

St. Clair West in Pictures A history of the communities of Carlton, Davenport, Earlscourt, and Oakwood Third Edition Revised and Expanded 1 Nancy Byers and Barbara Myrvold St Clair district west of Dufferin Street, 1890. Charles E. Goad, Atlas of the city of Toronto and vicinity, plate 40 and plate 41(section) Digitally merged. TRL 912.7135 G57.11 BR fo St. Clair West in Pictures A history of the communities of Carlton, Davenport, Earlscourt, and Oakwood Nancy Byers and Barbara Myrvold Third Edition Revised and Expanded Local History Handbook No. 8 a Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Back: Key to Abbreviations in Picture Credits and Notes Publication G. A. Reid. The Family, 1925/6. Interior murals, Dufferin/St. Clair Branch, Toronto Public Library. Adam Adam, G. Mercer. Toronto, Old and New. Byers, Nancy, 1924- Restored by Restorart Inc., 2004-7. Toronto: Mail Printing, 1891; Coles, 1974. St. Clair West in pictures : a history of the AO Archives of Ontario communities of Canton, Davenport, Earlscourt and Dufferin/St. Clair Branch is home to interior AO/Horwood Archives ofOntario. J. C. B. and Oakwood / Nancy Byers and Barbara Myrvold. -- 3rd murals painted between 1925 and 1932 by George E. C. Horwood Collection ed. rev. and expanded A. Reid (1860-1947), principal of the Ontario ATA Archdiocese of Toronto Archives College of Art, and two of Reid’s former students. CTA City of Toronto Archives (Local history handbook ; no. 8) Reid depicted “various aspects of community Careless Careless, J. M. S. Toronto to 1918. Includes bibliographical references and index. life.” His panel representing ‘The Family’ was Toronto: J. -

Mid-West Toronto Profile

Mid-West Toronto Sub-Region Profile September 19, 2016 This report was prepared by the following individuals: Thivya Sornalingam, Cynthia Damba, Ranjeeta Jhaveri, Mohamedraza Khaki, Myuri Elango Pandian, Kinga Byczko (Toronto Central LHIN Health Analytics and Innovation Team); Daniel Laidsky (Reconnect MHA Services). If you have any questions about this, please contact: Ranjeeta Jhaveri ([email protected]) and Cynthia Damba ([email protected]) 2 Table of Contents • Section 1 - Introduction to the Report and Mid-West Toronto sub-region………4 • Section 2 - Population Characteristics…………………………………………….11 • Section 3 – Health Status………………………..………………………………….29 • Section 4 – Health Service Use…………………….………………………………37 • Section 5 – Primary Care and Prevention………………………..……………….72 • Appendix A– Additional Information on Population Demographics……………..84 • Appendix B - Methodology for Identifying Primary Care Physicians……...…….90 3 Section 1. Introduction to the Report and Mid-West Toronto Sub-Region 4 Planning at the Sub-Region Level • One of the key Strategic Priorities that underpins the goals of the Toronto Central LHIN strategic plan is Taking a Population Health Approach, which will direct how we plan, prioritize, fund, and partner with other organizations to target the needs of the population and the sub-populations within. • This begins with a strong understanding of what our current and future patients’ needs and wants are in order to improve their health status and experience with health care. This information will help to identify neighbourhoods and population segments that may need targeted interventions to achieve the desired and equitable outcomes reflected in our goals. • A population based approach integrates the full spectrum of health care delivery – from preventing disease (e.g. -

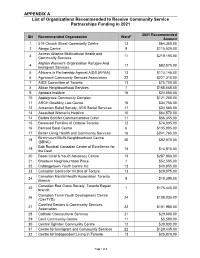

Community Service Partnerships Grant Allocation

APPENDIX A List of Organizations Recommended to Receive Community Service Partnerships Funding in 2021 2021 Recommended SN Recommended Organization Ward* Amount 1 519 Church Street Community Centre 13 $64,350.00 2 Abrigo Centre 9 $115,525.00 Access Alliance Multicultural Health and 3 11 $219,195.00 Community Services Afghan Women's Organization Refugee And 4 17 $82,075.00 Immigrant Services 5 Africans in Partnership Against AIDS (APAA) 13 $113,145.00 6 Agincourt Community Services Association 22 $221,310.00 7 AIDS Committee of Toronto 13 $75,700.00 8 Albion Neighbourhood Services 1 $165,085.00 9 Aphasia Institute 16 $24,560.00 10 Applegrove Community Complex $121,200.00 11 ARCH Disability Law Centre 10 $34,755.00 12 Armenian Relief Society, ARS Social Services 17 $24,560.00 13 Assaulted Women's Helpline 10 $64,570.00 14 Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic 11 $56,355.00 15 Bereaved Families of Ontario-Toronto 12 $74,035.00 16 Bernard Betel Centre 6 $135,005.00 17 Better Living Health and Community Services 16 $241,765.00 Birchmount Bluffs Neighbourhood Centre 18 20 $92,070.00 (BBNC) Bob Rumball Canadian Centre of Excellence for 19 15 $14,910.00 the Deaf 20 Boost Child & Youth Advocacy Centre 15 $287,960.00 21 Braeburn Neighbourhood Place 1 $52,505.00 22 Cabbagetown Youth Centre Inc. 13 $40,955.00 23 Canadian Centre for Victims of Torture 13 $29,075.00 Canadian Mental Health Association Toronto 24 8 $19,395.00 Branch Canadian Red Cross Society, Toronto Region 25 1 $175,445.00 branch Canadian Tamil Youth Development Centre 26 24 $138,035.00 -

Services for Seniors in TORONTO

Services for Seniors IN TORONTO HEALTH & WELLNESS / HOUSING / LEGAL & FINANCIAL HELP EDUCATION & EMPLOYMENT / TRANSPORTATION / RECREATION & MORE... SERVICES FOR SENIORS INTRODUCTION Introduction elcome to the governments and non-prot waiting lists, catchment areas rst edition of organizations. ese are or other criteria that may not “Services for oered in Toronto unless be listed. WSeniors” from the City of otherwise indicated. Services Also, information may Toronto’s Shelter, Support are grouped according to have changed since time of and Housing Administration subject with an index provided publication. Please call ahead Division. e focus of this at the back to help you locate to verify information and guide is to provide vulnerable information. avoid a wasted trip. seniors and their caregivers While general information with information about For more information about service access services that can help them to about this or other service and eligibility criteria is maintain their independence directories, contact provided along with service and stay housed. e listings [email protected]. descriptions, it is important to are restricted to programs note that many programs have and services provided by ISBN 978-1-895739-69-5 JG1310v2 Services for Seniors IN TORONTO 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS Crisis and Emergency ................................................................4 General Information and Referral ..............................................5 Elder Abuse ...........................................................................6-7 -

Ce Document Est Tiré Du Registre Aux Fins De La

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. ~ TQllOI\IIDERITAGE TRUST Ulli S. Watkiss City Clerk City Clerk's Office Secretariat Tel : 416-392-7033 NOV- 1 1 1017 Ellen Devlin Fax: 41 6-397-0111 Toronto and East York Community Council e-mail: [email protected] City Hall, 2nd Floor, West Web: www.toronto.ca 100 Queen Street West RECEIVED Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 IN THE MATTER OF THE ONTARIO HERITAGE ACT R.S.O. 1990 CHAPTER 0.18 AND CITY OF TORONTO, PROVINCE OF ONTARIO 6 FRANK CRESCENT NOTICE OF INTENTION _TO DES!GNATE . Ontario Heritage Trust 1O Adelaide Street East Toronto, Ontario MSC 1J3 Take notice that Toronto City Council intends to designate the lands and buildings known municipally as 6 Frank Crescent under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act. Reasons for Designation The property at 6 Frank Crescent (Chester B. Hamilton house) is worthy of designation under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act for its cultural heritage value, and meets Ontario Regulation 9/06, the provincial criteria prescribed for municipal designation under all three categories of design, associative and contextual value. Description The property at 6 Frank Crescent contains the former Chester B. Hamilton house (1924) , a two-and-a-half storey brick house, located on the west side of Frank Crescent between Hillcrest Drive and Bracondale Hill Road. -

Backgroundfile-49637.Pdf

p. ii Wayfinding System Strategy (Phase One) for the City of Toronto The City of Toronto has embarked on a planning process to develop a unified and coherent Wayfinding System. This report documents the processes and outcomes of the strategy phase of the study and will serve to inform the City’s decision on whether to carry the project forward into implementation. For further Acknowledgments - Steering Committee information please contact: Judy Morgan PF&R Partnerships, Fiona Chapman City of Toronto, Manager Transport Services Tourism - Program Adam Popper (416)392-0828 Support, Director City of Toronto, PF&R - fchapma@ Tobias Novogrodsky Policy Planning, Policy toronto.ca City of Toronto, Officer (Alternate) Strategic & Briana Illingworth Prepared for the Corporate- Metrolinx, Strategic City of Toronto by: Corporate Policy, Policy & Systems Sr Corp Mmt & Planning, Advisor Steer Davies Gleave Policy Consultant 1500-330 Bay Street John Forestieri Toronto, ON Allen Vansen Metrolinx, Signage M5H 2S8 Pan Am 2015, Services, Supervisor Toronto 2015 Pan/ in association with: Parapan American Michael Johnston, DIALOG Games, CEO Go Transit, Capital Infrastructure, Katie Ozolins Manager, Standards Completed in Pan Am 2015, August 2012 Toronto 2015 Pan/ Hilary Ashworth All images by Steer Parapan American RGD Ontario, Executive Davies Gleave unless Games, Operations Director (Alternate) otherwise stated. Associate Lionel Gadoury (Alternate) RGD Ontario, President Tim Laspa John Kiru City of Toronto, TABIA, Executive City Planning, Director Program Manager Michael Comstock Roberto Stopnicki TABIA, President City of Toronto, (Alternate) Transportation Pam Laite Services - Traffic Tourism Toronto, Mgmt, Director Member Care, Director (Retired) Harrison Myles Currie TTC , Wayfinding & City of Toronto, Signage, Co-ordinator Transportation John Mende Services - Traffic City of Toronto, Mgmt, Director Transportation Services- Rob Richardson Infrastructure, Director City of Toronto, Wayfinding System Strategy (Phase One) for the City of Toronto p. -

C 340 Representation Act Ontario

Ontario: Revised Statutes 1950 c 340 Representation Act Ontario © Queen's Printer for Ontario, 1950 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/rso Bibliographic Citation Representation Act, RSO 1950, c 340 Repository Citation Ontario (1950) "c 340 Representation Act," Ontario: Revised Statutes: Vol. 1950: Iss. 4, Article 28. Available at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/rso/vol1950/iss4/28 This Statutes is brought to you for free and open access by the Statutes at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ontario: Revised Statutes by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. REPRESENTATION Chap. 340 477 CHAPTER 340 The Representation Act 1. Notwithstanding anything in any general or special Act Municipal **°""***"®®" the boundaries of any county, territorial district, city, town, village or township shall for the purposes of this Act be deemed to be the boundaries of such county, territorial district, city, town, village or township as defined by statute, by-law, proclamation or other lawful authority on the 16th day of May, 1934. R.S.O. 1937, c. 6, s. 1. 2. The Assembly shall consist of 90 members. R-S.O. Number^of 1937, c. 6, s. 2. 3. Ontario shall for the purpose of representation in the Division of "° Assembly be divided into electoral districts as enumerated into and defined in the Schedule to this Act and one member shall diltricte. be returned to the Assembly for each electoral district. R.S.O. 1937, c. 6, s. 3. 4. The boundaries of any electoral district as set out in the changes in Schedule to this Act shall not be affected by any alteration boundaries, in municipal boundaries made after the 16th day of May, 1934.