Paving the Way to Paradise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Wychwood Park Wychwood Park Sits on a Height of Land That Was Once the Lake Iroquois Shore

Wychwood Park Wychwood Park sits on a height of land that was once the Lake Iroquois shore. The source for Taddle Creek lies to the north and provides the water for the pond found in the centre of the Park. Today, Taddle Creek continues under Davenport Road at the base of the escarpment and flows like an underground snake towards the Gooderham and Worts site and into Lake Ontario. Access to this little known natural area of Toronto is by two entrances one at the south, where a gate prevents though traffic, and the other entrance at the north end, off Tyrell Avenue, which provides the regular vehicular entrance and exit. A pedestrian entrance is found between 77 and 81 Alcina Avenue. Wychwood Park was founded by Marmaduke Matthews and Alexander Jardine in the third quarter of the 19th century. In 1874, Matthews, a land- scape painter, built the first house in the Park (6 Wychwood Park) which he named “Wychwood,” after Wychwood Forest near his home in England. The second home in Wychwood Park, “Braemore,” was built by Jardine a few years later (No. 22). When the Park was formally established in 1891, the deed provided building standards and restrictions on use. For instance, no commercial activities were permitted, there were to be no row houses, and houses must cost not less than $3,000. By 1905, other artists were moving to the Park. Among the early occupants were the artist George A. Reid (Uplands Cottage at No. 81) and the architect Eden Smith (No. 5). Smith designed both 5 and 81, as well as a number of others, all in variations of the Arts and Crafts style promoted by C.F.A. -

March 1, 2017 Time: 9:30 A.M

City Planning Division Anita MacLeod Committee of Adjustment Manager & Deputy Secretary Treasurer City Hall 100 Queen Street West Toronto ON M5H 2N2 Tel: 416-392-7565 Fax: 416-392-0580 COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT AGENDA TORONTO EAST YORK PANEL Hearing Date: March 1, 2017 Time: 9:30 a.m. Location: Committee Room - Toronto City Hall - 100 Queen Street West 1. OPENING REMARKS Declarations of Interest Confirmation of Minutes from Previous Hearing Closed & Deferred Files 2. DEPUTATION ITEMS The following applications will be heard at 9:30 a.m. or shortly thereafter: File Number Property Community (Ward) 1. A1114/16TEY 76 ROSEHEATH AVE Beaches-East York (32) 2. A1115/16TEY 44 MCGILL ST Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 3. A1116/16TEY 2154 QUEEN ST E Beaches-East York (32) 4. A1117/16TEY 159 HUDSON DR Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 5. A1119/16TEY 34 BELLWOODS AVE Trinity-Spadina (19) 6. A1120/16TEY 1090 - 1092 Toronto-Danforth (29) DANFORTH AVE 7. A1122/16TEY 354 MAIN ST Beaches-East York (31) 8. A1123/16TEY 554 DUFFERIN ST Davenport (18) 9. A1124/16TEY 173 TORRENS AVE Toronto-Danforth (29) 10. A1125/16TEY 97 LESMOUNT AVE Toronto-Danforth (29) 11. A1126/16TEY 97 A GRANBY ST Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 12. A1127/16TEY 220 ROBERT ST Trinity-Spadina (20) 13. A1128/16TEY 65 HAMMERSMITH Beaches-East York (32) AVE 14. A1174/16TEY 31 SUMMERHILL Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) AVE 15. A1276/16TEY 591 DUNDAS ST E (51 Toronto Centre-Rosedale (28) WYATT AVE) 1 The following applications will be heard at 1:30 p.m. or shortly thereafter: File Number Property Community (Ward) 16. -

December 1982

TORONTO FIELD NATURALIST Number 352, December 1982 Br-id~ing the years ••• Sec page 2 TFN 352 This Month's Cover "The Old Mill Bridge", sketched in the field by Mary Cumming In May 1840 a British army officer visited William Gamble's flourmill at the site of the present Old Mill and wrote this interesting description of the Humber Valley where the Old Mill Bridge now stands : "This mi 11 is on the right bank of the Humber about three mi 1es from the 1ake in a small circular valley bounded partly by abrupt banks and partly by rounded ;1 knolls . At the upper end the highlands approach one another forming a narrow i gorge clothed with heavy masses of the original forest. The basin of the gorge ! is completely filled by the river, which issues from it in a narrow stream flow j ing over a stony channel; but below the mill the water becomes deep and quiet i and deviates into two branches to form a small wooded island. "Close to the water's edge is a large mill surrounded by a number of small cottages over the chimneys of which rose the masts of flour barges; and on the bank above, in the midst of green lawn bounded by the forest is a neat white frame mansion commanding a fine view of this pretty spot. 11 The circular valley referred to is presumably the former Marsh 8, now part of King's Mill Park immediately downstream from Bloor Street, which was then used for pasture and cornfields. -

June 1990 OHS Bulletin, Issue 66

QEIi:::r.2z 5151 Yonge Street Willowdalc, Ontario MZN SP5 Hands on History Holiday By Lorraine Lowry wheat, and learn the intricacies and the products of your labours Workshop Co-ordinator of quillwork (paper filigree) as to take home as momentos of well as embroider a sampler. this unique experience. Homespun and hand made ar- This programme is designed This programme will be ticles from the past are modern for both the interested beginner presented in memory of witnesses to the skills that early and the spirited professional. It Elizabeth Campbell who shared Ontario settlers used on a daily will give the participants a basic her very special skills and basis in their homes, on their introduction to each of the craffs knowledge with so many people. farms and in their shops. and skills so that they can be When Elizabeth passed away Everyone in 19th century On- pursued either for personal in- suddenly in the Fall of 1988, tario had a working knowledge terest or for group programmes. The Gibson House Volunteers of a wide range of handcrafts that made a generous donation to were needed to survive, to pro- The same programme will be The Ontario Historical Society vide decoration and to bring offered on July 9, 10 and 11 and in her memory and those funds good luck to their families. again on August 10, 11 and 12 will now be used to support the Hands on History Holiday from 10:00 a.m. until 4:00 p.m. two Hands on History Holi- will explore some of those crafts daily at Black Creek Pioneer day programmes. -

Women's Suffrage in Ontario the Beginning of Women’S Suffrage Movements

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY an educational resource OF ONTARIO MESSAGE TO TEACHERS This educational resource was developed to compliment the documentary Women Should Vote: A Short History of how Women Won the Franchise in Ontario (www.ola.org/en/visit-learn/ about-ontarios-parliament/womens-suffrage-ontario), A NOTE ON LANGUAGE which tells the story of the struggle for women’s Some historical terms used in this resource are suffrage in Ontario at the turn of the 20th century. no longer in common use. First Nations peoples in Canada were initially called “Indians” by colonial It invites students to deepen their understanding of Europeans. This term is no longer used, though gender equality and democracy through examining and “Status Indian” is still a legal definition and is analyzing the suffrage movement, and facilitates mentioned throughout this guide. “Status Indian” engaging discussions and activities. Students will does not include all Indigenous peoples – for examine issues of identity, equity, activism and example, Métis and Inuit are excluded (see the justice in historical and contemporary contexts. Glossary on Page 22 for more information). CONTENTS The Suffrage Movement in Running the Good Race ............. 9 Glossary ......................... 22 Ontario: Votes for Women ............ 2 Indigenous Suffrage ............... 11 Activities The Beginning of Women’s Clues from the Archives Suffrage Movements ................ 3 Final Reflections ..................13 (Designed for Grades 8-12) .......23 Should I Support the Vote? The Long Road Timeline of Women’s Suffrage (Designed for Grades 4-7) ........24 to Women’s Suffrage ................ 4 in Ontario and Canada ............. 14 Our Rights Today ................25 A New Century ..................... 5 Feature Figures Appendix A ...................... -

2013-05-TFN-Newsletter.Pdf

Number 596 May 2013 Groundhog photographed by Moy Nahon in Edwards Gardens, May 2011 (see p 19) FEATURES REGULARS th Coming Events 25 90 Anniversary Event 17 Extracts from Outings Reports 14 Toronto’s Staff-Tree Shrubs 18 In the News 21 TFN Grants Report 20 Keeping in Touch 19 Monthly Meetings Notice 3 Arils of Staff-tree Shrubs 20 Monthly Meeting Report 13 Toronto’s Future Climate Study 22 President’s Report 12 The Global Warming Trend: TFN Outings 4 23 A view from Toronto Weather – This Time Last Year 22 Membership Renewal 27 TFN 596-2 May 2013 Toronto Field Naturalist is published by the Toronto Field BOARD OF DIRECTORS Naturalists, a charitable, non-profit organization, the aims of President & Outings Margaret McRae which are to stimulate public interest in natural history and Past President Bob Kortright to encourage the preservation of our natural heritage. Issued Vice President & monthly September to December and February to May. Monthly Lectures Nancy Dengler Views expressed in the Newsletter are not necessarily those Secretary-Treasurer Charles Crawford of the editor or Toronto Field Naturalists. The Newsletter is Communications Alexander Cappell printed on 100% recycled paper. Membership & Newsletter Judy Marshall ISSN 0820-636X Monthly Lectures Corinne McDonald Monthly Lectures Lavinia Mohr IT’S YOUR NEWSLETTER! Nature Reserves & Charles Bruce- We welcome contributions of original writing of observa- Outings Thompson tions on nature in and around Toronto (up to 500 words). Outreach Tom Brown We also welcome reports, reviews, poems, sketches, pain- Webmaster Lynn Miller tings and digital photographs. Please include “Newsletter” in the subject line when sending by email, or on the MEMBERSHIP FEES envelope if sent by mail. -

Leaside Heritage Appreciation Event Fall 2012

Leaside Heritage Appreciation Event Fall 2012 Objectives To inform, educate and plan to move forward as a community in order to protect the significant built heritage resources of Leaside. The run-up year to the Town of Leaside’s Centennial (April 23 2013) is an opportune time to start the conversation. Agenda The session would include the following elements: • The history of the growth and development of Leaside • The “character” of Leaside and the current planning, building demolition, and built heritage challenges • Lessons from other places (e.g. Mount Royal) • Alternative strategies such as Heritage Conservation District(s) and their implications (e.g. property values) Background Heritage preservation is not only about saving old (and sometimes not so old) buildings, rather it is about maintaining a unique quality of place, about enhancing the quality of life, and about supporting the cultural and economic vitality that accompanies areas with high conservation values (such as Wychwood Park, Rosedale, Cabbagetown). Leaside was a “model town”, planned in complete detail before a single building was erected – its 1912 street and lot plan was the work of landscape architect Frederick Todd, who designed Mount Royal in Montreal. When development got going in the 1930s and 40s Georgian and Tudor Revival styles were favoured by its developers, of whom the most well known is Henry Howard Talbot our home town developer-Mayor. In Leaside today there are several protected properties but except for the Talbot apartments on Bayview, they are nearly all from the estates of the late 19 th century, such as 262 Bessborough (the Elgie House). -

Vertical Files (PDF)

Wychwood Branch Local History Collection Vertical File Subject Headings Aboriginal history of Toronto Ardwold Gate Artists Austin, James, 1813-1897 Authors Baldwin family Bathurst-St. Clair Planning Area Bathurst Street Bathurst-Vaughan Triangle Biographies Blake, William Hume, 1809-1870 Bracondale Buildings Businesses Casa Loma Cedarvale Cedarvale Ravine Cemeteries Christie Street Veterans’ Hospital Churches City planning Community History Project Corrigan, William James Councillors Crime Currelly, Charles Trick Davenport Road Day care centers Directories Earlscourt Eastern College Eaton, John Craig, Sir, 1876-1922 and family Eaton, Timothy, 1834-1907 Elections--Canada Entertainment Famous visitors Fleming, Robert James Forest Hill Gage, William James Garrison Creek Geological features Hahn, Gustav Hemingway, Ernest Hillcrest Hillcrest Hospital Hillcrest Information and Research Centre Hillcrest Public School Holy Rosary Church and School Housing Hughes, W. J. (Cornflower glass manufacturer) Humewood House Irishtown (St. Clair and Bathurst) Lennox, Edward James, 1854-1933 Local history collections--Management Local history websites Lyndhurst Lodge Maps - Early Mayors McMillan, Neil Matthews, Marmaduke, 1837-1913 Mayors Na-Me-Res (Native Men’s Residence) Nordheimer, Samuel, 1824-1912 North Toronto Oakwood Youth Centre Old Toronto Advocate Parks Pellatt, Henry Mill, Sir, 1859-1939 Politics and Government Ravines Real Estate Reid, G. A. (George Agnew), 1860-1947 Rise (Condominium) Schools Smith, Eden, 1860-1949 Spadina Spadina Museum Spadina -

West Toronto Pg

What’s Out There? Toronto - 1 - What’s Out There - Toronto The Guide The Purpose “Cultural Landscapes provide a sense of place and identity; they map our relationship with the land over time; and they are part of our national heritage and each of our lives” (TCLF). These landscapes are important to a city because they reveal the influence that humans have had on the natural environment in addition to how they continue to interact with these land- scapes. It is significant to learn about and understand the cultural landscapes of a city because they are part of the city’s history. The purpose of this What’s Out There Guide-Toronto is to identify and raise public awareness of significant landscapes within the City of Toron- to. This guide sets out the details of a variety of cultural landscapes that are located within the City and offers readers with key information pertaining to landscape types, styles, designers, and the history of landscape, including how it has changed overtime. It will also provide basic information about the different landscape, the location of the sites within the City, colourful pic- tures and maps so that readers can gain a solid understanding of the area. In addition to educating readers about the cultural landscapes that have helped shape the City of Toronto, this guide will encourage residents and visitors of the City to travel to and experience these unique locations. The What’s Out There guide for Toronto also serves as a reminder of the im- portance of the protection, enhancement and conservation of these cultural landscapes so that we can preserve the City’s rich history and diversity and enjoy these landscapes for decades to come. -

The Woman Candidate for the Ontario Legislative Assembly, 1919-1929 Frederick Brent Scollie

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 11:37 Ontario History The Woman Candidate for the Ontario Legislative Assembly, 1919-1929 Frederick Brent Scollie Volume 104, numéro 2, fall 2012 Résumé de l'article L’histoire brosse un tableau sombre du manque de succès électoral des femmes URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065435ar ontariennes après 1919, l’année où elles ont obtenu le droit d’être élues à la DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1065435ar législature et aux conseils municipaux. Nous examinons de près treize des 21 femmes qui ont posé leur candidature à l’Assemblée législative de l’Ontario Aller au sommaire du numéro avant 1943, notamment les douze qui furent candidates entre 1919-1929, toutes vaincues, le succès politique de quelques-unes de leurs prédécesseurs élues à des commissions scolaires dès 1892, et l’expérience de ces femmes avec les Éditeur(s) partis politiques. Cela nous permet de vérifier les thèses et explications offertes par la politologue Sylvia Bashevkin et la sociologue Thelma McCormack sur le The Ontario Historical Society comportement politique des femmes au Canada anglais. ISSN 0030-2953 (imprimé) 2371-4654 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Scollie, F. B. (2012). The Woman Candidate for the Ontario Legislative Assembly, 1919-1929. Ontario History, 104(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065435ar Copyright © The Ontario Historical Society, 2012 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

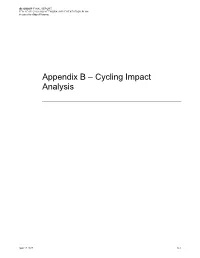

Appendix B – Cycling Impact Analysis

IBI GROUP FINAL REPORT TEN YEAR CYCLING NETWORK IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Prepared for City of Toronto Appendix B – Cycling Impact Analysis April 17, 2017 B-1 IBI GROUP FINAL REPORT TEN YEAR CYCLING NETWORK IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Prepared for City of Toronto Exhibit B-1: Criteria and Data Sources for Cycling Impact Analysis Criterion Operational Criteria Source Current demand Number of trips beginning or ending within a TTS 2011 500 m buffer around the project Trip mode: bicycle Potential demand Number of trips beginning or ending within a TTS 2011 500 m buffer around the project Trip mode: all motorized modes Trip distance: equal to or less than 5 km Population and Number of residents or employees within the City of Toronto employment density 500 m buffer around the project 2011 Network coverage Area within the 500 m buffer around the City of Toronto project not covered by the 250 m / 500 m Cycling buffers around an existing facilities Network 2015 250 m buffers used for existing facilities in the Area 1 500 m buffers used for existing facilities in the Area 2 Trip generators Number of trip generators near which the City of Toronto project passes 2015 Counted if the projects intersects the 250 m radius around the generator Generators counted are: mobility hub, major rapid transit station, university, school Safety Number of cycling accident sites near which City of Toronto the project passes 2015 Counted if the project intersects the 25 m radius around the accident site Barrier crossings Number of crossings through barriers to City