St. Clair West in Pictures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

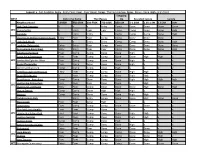

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Fixer Upper, Comp

Legend: x - Not Available, Entry - Entry Point, Fixer - Fixer Upper, Comp - The Compromise, Done - Done + Done, High - High Point Stepping WEST Get in the Game The Masses Up So-called Luxury Luxury Neighbourhood <$550K 550-650K 650-750K 750-850K 850-1M 1-1.25M 1.25-1.5M 1.5-2M 2M+ High Park-Swansea x x x Entry Comp Done Done Done Done W1 Roncesvalles x Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High Parkdale x Entry Entry x Comp Comp Comp Done High Dovercourt Wallace Junction South Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done x High Park North x x Entry Entry Comp Comp Done Done High W2 Lambton-Baby point Entry Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done Done Runnymede-Bloor West Entry Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Caledonia-Fairbank Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Corso Italia-Davenport Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High High x W3 Keelesdale-Eglinton West Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Rockcliffe-Smythe Fixer Comp Done Done Done High x x x Weston-Pellam Park Comp Comp Comp Done High x x x x Beechborough-Greenbrook Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x BriarHill-Belgravia x Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x Brookhaven--Amesbury Comp Comp Done Done Done High High High high Humberlea-Pelmo Park Fixer Fixer Fixer Done Done x High x x W4 Maple Leaf and Rustic Entry Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Done High Mount Dennis Comp Comp Done High High High x x x Weston Comp Comp Done Done Done High High x x Yorkdale-Glen Park x Entry Entry Comp Done Done High Done Done Black Creek Fixer Fixer Done High x x x x x Downsview Fixer Comp -

March 1, 2017 Time: 9:30 A.M

City Planning Division Anita MacLeod Committee of Adjustment Manager & Deputy Secretary Treasurer City Hall 100 Queen Street West Toronto ON M5H 2N2 Tel: 416-392-7565 Fax: 416-392-0580 COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT AGENDA TORONTO EAST YORK PANEL Hearing Date: March 1, 2017 Time: 9:30 a.m. Location: Committee Room - Toronto City Hall - 100 Queen Street West 1. OPENING REMARKS Declarations of Interest Confirmation of Minutes from Previous Hearing Closed & Deferred Files 2. DEPUTATION ITEMS The following applications will be heard at 9:30 a.m. or shortly thereafter: File Number Property Community (Ward) 1. A1114/16TEY 76 ROSEHEATH AVE Beaches-East York (32) 2. A1115/16TEY 44 MCGILL ST Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 3. A1116/16TEY 2154 QUEEN ST E Beaches-East York (32) 4. A1117/16TEY 159 HUDSON DR Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 5. A1119/16TEY 34 BELLWOODS AVE Trinity-Spadina (19) 6. A1120/16TEY 1090 - 1092 Toronto-Danforth (29) DANFORTH AVE 7. A1122/16TEY 354 MAIN ST Beaches-East York (31) 8. A1123/16TEY 554 DUFFERIN ST Davenport (18) 9. A1124/16TEY 173 TORRENS AVE Toronto-Danforth (29) 10. A1125/16TEY 97 LESMOUNT AVE Toronto-Danforth (29) 11. A1126/16TEY 97 A GRANBY ST Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) 12. A1127/16TEY 220 ROBERT ST Trinity-Spadina (20) 13. A1128/16TEY 65 HAMMERSMITH Beaches-East York (32) AVE 14. A1174/16TEY 31 SUMMERHILL Toronto Centre-Rosedale (27) AVE 15. A1276/16TEY 591 DUNDAS ST E (51 Toronto Centre-Rosedale (28) WYATT AVE) 1 The following applications will be heard at 1:30 p.m. or shortly thereafter: File Number Property Community (Ward) 16. -

Trailside Esterbrooke Kingslake Harringay

MILLIKEN COMMUNITY TRAIL CONTINUES TRAIL CONTINUES CENTRE INTO VAUGHAN INTO MARKHAM Roxanne Enchanted Hills Codlin Anthia Scoville P Codlin Minglehaze THACKERAY PARK Cabana English Song Meadoway Glencoyne Frank Rivers Captains Way Goldhawk Wilderness MILLIKEN PARK - CEDARBRAE Murray Ross Festival Tanjoe Ashcott Cascaden Cathy Jean Flax Gardenway Gossamer Grove Kelvin Covewood Flatwoods Holmbush Redlea Duxbury Nipigon Holmbush Provence Nipigon Forest New GOLF & COUNTRY Anthia Huntsmill New Forest Shockley Carnival Greenwin Village Ivyway Inniscross Raynes Enchanted Hills CONCESSION Goodmark Alabast Beulah Alness Inniscross Hullmar Townsend Goldenwood Saddletree Franca Rockland Janus Hollyberry Manilow Port Royal Green Bush Aspenwood Chapel Park Founders Magnetic Sandyhook Irondale Klondike Roxanne Harrington Edgar Woods Fisherville Abitibi Goldwood Mintwood Hollyberry Canongate CLUB Cabernet Turbine 400 Crispin MILLIKENMILLIKEN Breanna Eagleview Pennmarric BLACK CREEK Carpenter Grove River BLACK CREEK West North Albany Tarbert Select Lillian Signal Hill Hill Signal Highbridge Arran Markbrook Barmac Wheelwright Cherrystone Birchway Yellow Strawberry Hills Strawberry Select Steinway Rossdean Bestview Freshmeadow Belinda Eagledance BordeauxBrunello Primula Garyray G. ROSS Fontainbleau Cherrystone Ockwell Manor Chianti Cabernet Laureleaf Shenstone Torresdale Athabaska Limestone Regis Robinter Lambeth Wintermute WOODLANDS PIONEER Russfax Creekside Michigan . Husband EAST Reesor Plowshare Ian MacDonald Nevada Grenbeck ROWNTREE MILLS PARK Blacksmith -

The Simcoe Legacy: the Life and Times of Yonge Street

The Simcoe Legacy: The Life and Times of Yonge Street The Ontario Historical Society The Simcoe Legacy: The Life and Times of Yonge Street A collection of the papers from the seminar which explored the legacy of John Graves Simcoe, Upper Canada's first Lieutenant Governor, and his search for a route to Canada's interior that led to the building of the longest street in the world. The Ontario Historical Society 1996 © The Ontario Historical Society 1996 Acl~nowledgement_s The Simcoe Legacy: The Life and Times of Yonge Street is a publication of The Ontario Historical Society in celebration of the 200th anniversary of Yonge Street. The Ontario Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the support of the John Graves Simcoe Association, which amalgamated with the Society in 1992, and the Ministry of Citizenship, Culture and Recreation. Editing: Wyn Millar Typesetting and Production: Meribeth Clow The Ontario Historical Society 34 Parkview A venue Willowdale, Ontario M2N3Y2 ( 416) 226-9011 Fax (416) 226-2740 © 1996 ISBN# 0-919352-25-1 © The Ontario Historical Society 1996 Table of Contents Foreword Wyn Millar.......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction Linda Kelly .......................................................................................................................................... 2 The Mississauga and the Building of Yonge Street, 1794-1796 Donald B. Smith................................................................................................................................. -

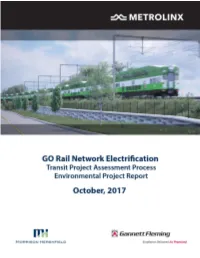

Volume 5 Has Been Updated to Reflect the Specific Additions/Revisions Outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, Dated November, 2017

DISCLAIMER AND LIMITATION OF LIABILITY This Revised Final Environmental Project Report – Volume 5 has been updated to reflect the specific additions/revisions outlined in the Errata to the Environmental Project Report, dated November, 2017. As such, it supersedes the previous Final version dated October, 2017. The report dated October, 2017 (“Report”), which includes its text, tables, figures and appendices) has been prepared by Gannett Fleming Canada ULC (“Gannett Fleming”) and Morrison Hershfield Limited (“Morrison Hershfield”) (“Consultants”) for the exclusive use of Metrolinx. Consultants disclaim any liability or responsibility to any person or party other than Metrolinx for loss, damage, expense, fines, costs or penalties arising from or in connection with the Report or its use or reliance on any information, opinion, advice, conclusion or recommendation contained in it. To the extent permitted by law, Consultants also excludes all implied or statutory warranties and conditions. In preparing the Report, the Consultants have relied in good faith on information provided by third party agencies, individuals and companies as noted in the Report. The Consultants have assumed that this information is factual and accurate and has not independently verified such information except as required by the standard of care. The Consultants accept no responsibility or liability for errors or omissions that are the result of any deficiencies in such information. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are valid as of the date of the Report and are based on the data and information collected by the Consultants during their investigations as set out in the Report. The opinions, advice, conclusions and recommendations in the Report are based on the conditions encountered by the Consultants at the site(s) at the time of their investigations, supplemented by historical information and data obtained as described in the Report. -

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

DUFFERIN STREET UNDERPASS Toronto, Ontario

Canadian Consulting Engineering Awards 2011 Project Entry for DUFFERIN STREET UNDERPASS Toronto, Ontario Association of Consulting Engineering Companies Dufferin Street Underpass 2011 Awards Toronto, Ontario TABLE OF CONTENTS Signed Official Entry Form ................................................................................ i Entry Consent Form ......................................................................................... ii PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS .................................................................................................. 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................ 1 TOC iii Association of Consulting Engineering Companies Dufferin Street Underpass 2011 Awards Toronto, Ontario PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS For more than one hundred years, the southbound journey on Dufferin Street in Toronto, Ontario was stopped short by a major, multi-track rail corridor. Cars, buses and emergency vehicles alike were forced to turn left, entering the infamous "Dufferin Jog". This three block circuitous route through a residential neighborhood added only time and confusion to those wishing to travel further south. Delcan was contracted to remedy this by designing and engineering a smart solution that would seamlessly link the two parts of Dufferin Street. The City of Toronto billed this project as an exercise in "urban place-making", wanting to both improve access and revitalize a community at the same time. Delcan's crisp urban design met these requirements -

Evaluation of Potential Impacts of an Inclusionary Zoning Policy in the City of Toronto

The City of Toronto Evaluation of Potential Impacts of an Inclusionary Zoning Policy in the City of Toronto May 2019 The City of Toronto Evaluation of Potential Impacts of an Inclusionary Zoning Policy in the City of Toronto Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. ii 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Housing Prices and Costs – Fundamental Factors ...................................................................... 2 3.0 Market Context ........................................................................................................................... 8 4.0 The Conceptual Inclusionary Zoning Policy .............................................................................. 12 5.0 Approach to Assessing Impacts ................................................................................................ 14 6.0 Analysis ..................................................................................................................................... 21 7.0 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................... 34 Disclaimer: The conclusions contained in this report have been prepared based on both primary and secondary data sources. NBLC makes every effort to ensure the data is correct but cannot guarantee -

We Want the Airport Subway Now!

Stop #1, Pearson Airport: There are over 70,000 total Stop #8, Junction (Dupont): West Toronto Junction is on-site employees from the airlines, aviation support, an historically significant neighbourhood of 12,000 passenger services, retail, food and beverage, and the people. The subway would serve this important retail federal government (see: GTAA website). and residential area. WE WANT THE Stop #2, Woodbine (Hwy 27): “Located in northwest Stop#9, Brockton Village (Bloor Street): Direct Toronto, the Humber North Campus is a community connection to the Bloor Street Subway. The new line AIRPORT SUBWAY within the larger Toronto community. It is home to could be built to permit eastbound Bloor trains to take a more than 10,000 full-time students, over 1,000 of them shortcut downtown or westbound Bloor trains to go out NOW! living on campus and over 50,000 part-time students.” to the airport. (see: Humber College website) Stop #10, Parkdale, (Queen/King Streets W.): Over Stop #3, Rexdale (Kipling Ave.): Over 42,000 people 50,000 people live in the three adjacent neighbourhoods live in the three neighbourhoods adjacent to this station; and they would be only two stops from Union Station! many of them are new Canadians. Currently it is proposed to construct an elite, Stop #11, Fort York (Strachan): This stop will serve private, express train service between Union Stop #4, Weston Village (Lawrence Ave.): Over the new Liberty Village area as well as King Street Station and Pearson Airport with a stop at the 17,000 people live within walking distance of this West. -

20 Frank Crescent, Toronto on M6G3K5 Virtual Tour 2016-05-16, 12:41 PM

20 Frank Crescent, Toronto ON M6G3K5 Virtual Tour 2016-05-16, 12:41 PM 20 FRANK CRESCENT, TORONTO ON M6G3K5 PRICE: $1,985,000 MLS #: C3484977 PROPERTY STYLE: 2.5 Storey PROPERTY TYPE: Residential BATHROOMS: 2 BEDROOMS: 5 PARKING: 3 STOREYS: 2 WATER SUPPLY: Municipal LAND SIZE: 55.00 x 106.00 EXTERIOR FINISH: Brick BASEMENT: Fully finished, Walk-out FUEL: Gas(natural) HEATING: Hot water GARAGE/DRIVEWAY: Attached, Triple drive FIRE PROTECTION: Alarm System NEARBY: Schools, Public Transit, Park, Playground, Recreation PROPERTY FEATURES: Eat-in kitchen Separate dining room In-lawIn-law suitesuite Alarm system Fireplace PROPERTY DESCRIPTION: An Elegant And Stately Home, On A Quiet Tree-Lined Street In Bracondale Hill, Steps To Hillcrest Park, Schools & Wychwood Barns Market. A 1930'S Architectural Style With 3,400Sf Of Living Space, A Classic Center Hall Plan With Great Bones. Large Living & Dining Rooms Perfect For Entertaining. Great Renovation Opportunity. Finished Bsmnt Walks Out To Large, Fenced, Tree'ed Backyard Garden. Attached Garage With Private Drive For 3. Open House Sat/Sun 2-4. Incl: Fridge,Stove,Washer & Dryer, Elfs And Window Coverings. Exclude Center Hall Chandelier. Floor Plans And Home Inspection Available Upon Request; [email protected]. No Survey. Most Plumbing And Electricals Upgraded Within 15 Yrs. http://houssmax.ca/vtour/c2289130#.Vzn3Wpnmgfg.email Page 1 of 4 20 Frank Crescent, Toronto ON M6G3K5 Virtual Tour 2016-05-16, 12:41 PM OPEN HOUSE SCHEDULE: Please call for a showing. VIDEO Welcome to 20 FrankGALLERY Crescent -

King Street East Properties (Leader Lane to Church Street) Date: June 14, 2012

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Intention to Designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act – King Street East Properties (Leader Lane to Church Street) Date: June 14, 2012 Toronto Preservation Board To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Urban Design, City Planning Division Wards: Toronto Centre-Rosedale – Ward 28 Reference P:\2012\Cluster B\PLN\HPS\TEYCC\September 11 2012\teHPS34 Number: SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council state its intention to designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act the properties identified in Recommendation No. 2. The properties are located on the south side of King Street East between Leader Lane and Church Street and contain a series of commercial and institutional buildings dating from the mid-19th to the early 20th century. The City has received an application for a zoning by-law amendment for the redevelopment of this block. Following research and evaluation, staff have determined that the King Street East properties meet Ontario Regulation 9/06, the provincial criteria prescribed for municipal designation under the Ontario Heritage Act. The designation of the properties would enable City Council to regulate alterations to the sites, enforce heritage property standards and maintenance, and refuse demolition. RECOMMENDATIONS City Planning Division recommend that: 1. City Council include the following properties on the City of Toronto Inventory of Heritage Properties: a. 71 King Street East (with a convenience address of 73 King Street East) b. 75 King Street East (with a convenience address of 77 King Street East) c. 79 King Street East (with a convenience address of 81 King Street East) Staff report for action – King Street East Properties – Intention to Designate 1 d.