Bathurst Manor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighbourhood Equity Scores for Toronto Neighbourhoods and Recommended Neighbourhood Improvement Areas

Appendix B Neighbourhood Equity Scores for Toronto Neighbourhoods and Recommended Neighbourhood Improvement Areas All Scores are out of a maximum 100 points: the lower the Score, the higher the level of total overall inequities faced by the neighbourhood. Neighbourhoods with Scores lower than the Neighbourhood Equity Benchmark of 42.89 face serious inequities that require immediate action. Neighbourhoods marked with "*" in the Rank column were designated by Council as Priority Neighbourhood Areas for Investment (PNIs) under the 2005 Strategy. For neighbourhoods marked with a "+" in the Rank column, a smaller portion of the neighbourhood was included in a larger Priority Neighbourhood Areas for Investment designated by Council under the 2005 Strategy. Neighbourhood Recommended Rank Neighbourhood Number and Name Equity Score as NIA 1* 24 Black Creek 21.38 Y 2* 25 Glenfield-Jane Heights 24.39 Y 3* 115 Mount Dennis 26.39 Y 4 112 Beechborough-Greenbrook 26.54 Y 5 121 Oakridge 28.57 Y 6* 2 Mount Olive-Silverstone-Jamestown 29.29 Y 7 5 Elms-Old Rexdale 29.54 Y 8 72 Regent Park 29.81 Y 9 55 Thorncliffe Park 33.09 Y 10 85 South Parkdale 33.10 Y 11* 61 Crescent Town 33.21 Y 12 111 Rockcliffe-Smythe 33.86 Y 13* 139 Scarborough Village 33.94 Y 14* 21 Humber Summit 34.30 Y 15 28 Rustic 35.40 Y 16 125 Ionview 35.73 Y 17* 44 Flemingdon Park 35.81 Y 18* 113 Weston 35.99 Y 19* 22 Humbermede 36.09 Y 20* 138 Eglinton East 36.28 Y 21 135 Morningside 36.89 Y Staff report for action on the Toronto Strong Neighbourhoods Strategy 2020 1 Neighbourhood Recommended -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Investment Insight

SOUL CONDOS INVESTMENT INSIGHT David Vu & Brigitte Obregon, Brokers RE/MAX Ultimate Realty Inc., Brokerage Cell: 416-258-8493 Cell: 416-371-3116 Fax: 416-352-7710 Email: [email protected] WWW.GTA-HOMES.COM BUFRILDINGA GROUPM Developer: FRAM Building Group Architect: Core Architects Landscape Architect: Baker Turner Port Street Market in Port Credit Riverhouse in East Village, Calgary Interior Designer: Union 31 Project Summary FR A M Phase 1: 2 buildings BUILDING GROUP w/ 403 units, 38 townhomes Creative. Passionate. Driven. This is the DNA of FRAM. Phase 2: 3 buildings An internationally acclaimed company that’s known w/ 557 units, 36 townhomes for its next level thinking, superior craftsmanship, bold architecture and ability to create dynamic Community: 7.2 Acres of new development lifestyles and communities where people love to live. 1 Acre public park A team that’s built on five generations of experience, professionalism and courage with a portfolio of over GODSTONE RD 11,000 residences across the GTA. 404 KINGSLAKE RDALLENBURY GARDENS North Shore in Port Credit First in East Village, Calgary FAIRVIEW MALL DR DVP, 401 INTERCHANGE FAIRVIEW MALL DON MILLS RD DON MILLS SHEPPARD AVE EAST 401 DVP SOUL CONDOS 3 A DYNAMIC, MASTER-PLANNED COMMUNITY AT FAIRVIEW Soul Condos at 150 Fairview Mall Drive is part of a dynamic master-planned 7.2 acre new development with a 1 acre public park. This community is destined to become a key landmark in this vibrant and growing North York neighbourhood. ACCESS ON RAMP TO DVP / 401 INTERCHANGES DVP FAIRVIEW -

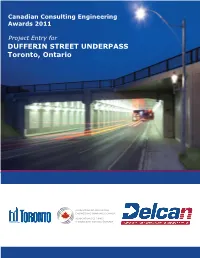

DUFFERIN STREET UNDERPASS Toronto, Ontario

Canadian Consulting Engineering Awards 2011 Project Entry for DUFFERIN STREET UNDERPASS Toronto, Ontario Association of Consulting Engineering Companies Dufferin Street Underpass 2011 Awards Toronto, Ontario TABLE OF CONTENTS Signed Official Entry Form ................................................................................ i Entry Consent Form ......................................................................................... ii PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS .................................................................................................. 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................ 1 TOC iii Association of Consulting Engineering Companies Dufferin Street Underpass 2011 Awards Toronto, Ontario PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS For more than one hundred years, the southbound journey on Dufferin Street in Toronto, Ontario was stopped short by a major, multi-track rail corridor. Cars, buses and emergency vehicles alike were forced to turn left, entering the infamous "Dufferin Jog". This three block circuitous route through a residential neighborhood added only time and confusion to those wishing to travel further south. Delcan was contracted to remedy this by designing and engineering a smart solution that would seamlessly link the two parts of Dufferin Street. The City of Toronto billed this project as an exercise in "urban place-making", wanting to both improve access and revitalize a community at the same time. Delcan's crisp urban design met these requirements -

Community Conversations: North York West Sub-Region

Central LHIN System Transformation Sub-region Planning Community Conversations: North York West Sub-region April 5, 2017 Setting the Stage for Today’s Discussions Kick off sub-region planning & share the Central LHIN strategy; Bring sub-region communities together to strengthen relationships through collaborative networking; Listen and reflect upon experiences of patients and providers as they move through the system; Create a common understanding of sub-regional attributes related to their communities and populations; Generate greater context of sub-region needs and attributes through collaborative discussion; Set the stage to co-create the system collectively to identify gaps in care continuity during transitions 2 Central LHIN Community Conversation North York West Sub-region Agenda Time Item Presenters 7:45 to 8:30 am Registration & Light Refreshments Sub Region Community Wall 8:30 am Overview of the Day Welcome & Kick Off Kim Baker Central LHIN Sub-region Strategy: Transitions Chantell Tunney 9:50 am Sharing Experiences in Care Guest Speaker: Central LHIN Resident Cottean Lyttle Guest Speaker: Care Provider Dr. Jerome Liu 9:50 pm BREAK 10:00 am Building a Foundation: Information Eugene Wong 11:00 am Filling in the Gaps Group Work 11:25 am Wrap Up & Next Steps Chantell Tunney 3 Integrated Health Service Plan 2016 - 2019 4 Sub-region Strategy Building momentum, leveraging local strengths and co-designing innovative approaches to care continuity 5 Population Health – What does it mean to take a Population Health approach? Population health allows us to address the needs of the entire population, while reminding us that special attention needs to be paid to existing disparities in health. -

Finch Avenue Sheppard Avenue Lawrence Ave. West Weston Rd . Sc Arlett Rd . Eglinton Ave. West Finch Avenue Sheppard Avenue

FUTURE VAUGHAN METROPOLITAN CENTRE SUBWAY STATION SHOPPING FUTURE HWY 407 SUBWAY STATION SHOPPING STEELES AVENUE FUTURE STEELES WEST UNIVERSITY SUBWAY STATION OF TORONTO INSTITUTE FOR DANBY AEROSPACE WOODS STUDIES ELM KEELE CAMPUS PARK JOHN SHOREHAM PARK BOOTH FUTURE BOYNTON MEMORIAL STONG YORK UNIVERSITY WOODS ARENA POND SUBWAY STATION SAYWELL WOODS G. ROSS LORD DUFFERIN STREET PARK DRIFTWOOD MALOCA 400 HULMAR COMMUNITY GARDEN PARK RECREATION CENTRE BLACK CREEK JANE STREET EDGLEY PARKLAND PARK FINCH HYDRO CORRIDOR RECREATIONAL TRAIL DRIFTWOOD FUTURE PARK FINCH HYDRO CORRIDOR FINCH WEST FIRE RECREATIONAL TRAIL SUBWAY STATION FINCH HYDRO CORRIDOR STATION GARTHDALE PARK RECREATIONAL TRAIL FOUNTAINHEAD PARK FINCH AVENUE JANE FINCH MALL DERRYDOWN PARK BRATTY TOPCLIFF PARK PARK SENTINEL PARK FIRGROVE PARK ELIA MIDDLE SCHOOL CHURCH CHURCH GRANDRAVINE PARK OAKDALE FUTURE PARK GRANDRAVINE SHEPPARD WEST FENNIMORE ARENA SUBWAY STATION PARK FIRE STATION SPENVALLEY CHURCH PARK STANLEY PARK ST. JANE BLESSED BROOKWELL KEELE STREET FRANCES DOWNSVIEW MARGHERITA NORHTWOOD PARK PARK CATHOLIC OF CITTA CASTELLO SCHOOL PARK SHOPPING SPORT CENTRE SILVIO CATHOLIC SCHOOL WILSON HEIGHTS BLVD COLELLA SHOPPING DOWNSVIEW BANTING PARK LIBRARY SHEPPARD AVENUE SUBWAY PARK ST. MARTHA STATION CHURCH DIANA CATHOLIC PARK SCHOOL ALLEN ROAD GILTSPUR PARK DOWNSVIEW BELMAR DELLS PARKETTE PARK LANGHOLM KEELE STREET WILSON OAKDALE GOLF & PARK COUNTRY CLUB HEIGHTS BEVERLEY HEIGHTS PARK 400 MIDDLE SCHOOL BLAYDON PUBLIC SCHOOL EXBURY PARK CHURCH ST. CONRAD JANE STREET CATHOLIC ST. GERARD HEATHROW SCHOOL DOWNSVIEW MAJELLA PARK SECONDARY ANCASTOR ANCASTER FIRE CATHOLIC TUMPANE RODING SCHOOL MT. SINAI PUBLIC PARK STATION WILSON SCHOOL PUBLIC COMMUNITY MEMORIAL SCHOOL SUBWAY SCHOOL CENTRE LIBRARY PARK ANCASTER ST. NORBERT STATION MODONNA COMMUNITY CATHOLIC CHALKFARM RODING SCHOOL PARK ST. -

Downsview Major Roads Environmental Study Report

City of Toronto Downsview Major Roads Municipal Class Environmental Assessment Environmental Study Report Prepared by: AECOM 30 Leek Crescent, Floor 4 905 882 4401 tel Richmond Hill, ON, Canada L4B 4N4 905 882 4399 fax www.aecom.com April, 2018 Project Number: 60306466 City of Toronto Downsview Area Major Roads Environmental Study Report Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name City of Toronto AECOM Canada Ltd. Rpt_2018-04-20_Damr_Final Esr_60306466 City of Toronto Downsview Area Major Roads Environmental Study Report Statement of Qualifications and Limitations The attached Report (the “Report”) has been prepared by AECOM Canada Ltd. (“AECOM”) for the benefit of the Client (“Client”) in accordance with the agreement between AECOM and Client, including the scope of work detailed therein (the “Agreement”). The information, data, recommendations and conclusions contained in the Report (collectively, the “Information”): . is subject to the scope, schedule, and other constraints and limitations in the Agreement and the qualifications contained in the Report (the “Limitations”); . represents AECOM’s professional judgement in light of the Limitations and industry standards for the preparation of similar reports; . may be based on information provided to AECOM which has not been independently verified; . has not been updated since the date of issuance of the Report and its accuracy is limited to the time period and circumstances in which it was collected, processed, made or issued; . must be read as a whole and sections thereof should not be read out of such context; . was prepared for the specific purposes described in the Report and the Agreement; and . in the case of subsurface, environmental or geotechnical conditions, may be based on limited testing and on the assumption that such conditions are uniform and not variable either geographically or over time. -

REPORT for ACTION Westbound U-Turn Prohibition

REPORT FOR ACTION Westbound U-Turn Prohibition - Sheppard Avenue East at Don Mills Road Date:September 19, 2019 To: North York Community Council From: Acting Director, Traffic Management, Transportation Services Wards: Ward 17, Don Valley North SUMMARY As the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) operates bus service on Sheppard Avenue East, City Council approval of this report is required. Transportation Services is requesting that City Council prohibit westbound U-turn movements at all times on Sheppard Avenue East at Don Mills Road. The proposed turn prohibition will address congestion concerns between Don Mills Road and the Don Valley Parkway. RECOMMENDATIONS The Acting Director, Traffic Management, Transportation Services recommends that: 1. City Council prohibit westbound U-turn movements at all times on Sheppard Avenue East at Don Mills Road. FINANCIAL IMPACT All costs associated with the U-turn prohibition signage are included within the Transportation Services 2019 Operating Budget. DECISION HISTORY This report addresses a new initiative. Westbound U-Turn Prohibition - Sheppard Avenue East at Don Mills Road Page 1 of 4 COMMENTS Transportation Services was requested by Councillor Shelley Carroll to investigate westbound delays for traffic turning left onto Don Mills Road from Sheppard Avenue East. Staff were advised that during the p.m. peak traffic is seen to back up eastwards on Sheppard Avenue East, from the Don Mills Road intersection to the exit ramps from the Don Valley Parkway (DVP). Sheppard Avenue East is classified as a major arterial roadway. At the eastern leg of the intersection with Don Mills Road it is 28 metres wide with a raised median, a westbound left-turn lane, two westbound through lanes and a westbound shared through/right-turn lane. -

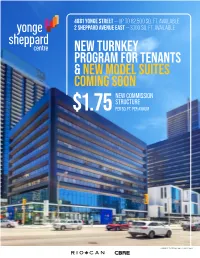

New Turnkey Program for Tenants & New Model Suites

4881 YONGE STREET — UP TO 82,500 SQ. FT. AVAILABLE 2 SHEPPARD AVENUE EAST — 3,100 SQ. FT. AVAILABLE NEW TURNKEY PROGRAM FOR TENANTS & NEW MODEL SUITES COMING SOON NEW COMMISSION STRUCTURE $1.75 PER SQ. FT. PER ANNUM +SUBJECT TO TERMS AND CONDITIONS. 2 SHEPPARD AVENUE EAST // 4881 YONGE STREET AVAILABILITIES 4881 Yonge Suite 303 ‒ 2,208 sq. ft. Model Suite Suite 305 ‒ 4,660 sq. ft. Model Suite 3rd Floor – 9,467 sq. ft. 4th Floor ‒ 16,488 sq. ft. A HASSLE-FREE 5th Floor ‒ 16,488 sq. ft. 6th Floor ‒ 16,492 sq. ft. 7th Floor ‒ 16,492 sq. ft. SOLUTION FOR 8th Floor ‒ 16,492 sq. ft. LEASED 2 Sheppard 3rd Floor ‒ 3,100 sq. ft. Model Suite TENANTS TIMING Immediate / Model Suites Aug 2021 Call agents to discuss FROM 2,000 – 82,500 SQ. FT. ASKING RATE ADDITIONAL RENT1 $20.32 per sq. ft. per annum (2021 Estimate) + RioCan will turnkey any suite with a 120 day turnaround 1Exclusive of Hydro & water + Finishes to include glass sidelights, upgraded lighting, PARKING 1:1,200 sq. ft. at $185 per month and all new window blinds + Selection of layouts available to choose from to suit your COMMISSION Now paying $1.75 PSF per annum up to 10 years specific needs for all new deals completed in 2021 + Premium finishes or furniture available upon request * Applicable for most build-outs, subject to change based on complexity 4881 YONGE STREET FOUR SIMPLE STEPS TO YOUR BRAND NEW OFFICE 1 2 3 4 PLAN PRICE PAPER PAY We’ll work with you We’ll price out your We will prepare the offer We’ll pay! Collect to design a space that design and offer on our short-form term your bonus fee suits your needs competitive rates for sheet your preferred term 4881 YONGE STREET FLOOR PLANS 3RD FLOOR | MODEL SUITES + New Model Suites coming August 2021 + Ability to source furniture for your client + High-end, tech ready finishes throughout + Suite 305 is divisible to 1,700 sq. -

Retail Plaza with Prime Redevelopment Potential Toronto, Ontario

824 177,179,181 SHEPPARD AVE W & COCKSFIELD AVE RETAIL PLAZA WITH PRIME REDEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL TORONTO, ONTARIO Accelerating success. 824 Sheppard Avenue West, Toronto MASSING CONCEPT Job No. 19255 | 08.26.2019 Plan View Massing Views Proposed Driveway Access Cocksfield Avenue Cocksfield Avenue 45.8m3.0m 2 ST. 3.0m 4 ST. 5.5m Wilmington Avenue 6 Sheppard Avenue West 22.0m ST. 7.5m Minimum 1,038 sq.m. Floorplate 10.9m Proposed 9-storey Mixed-use Building 12.9m Blairville Road 22.0m Northwest View 15.0m PROPERTY PROFILE 122.4m 2 ST. 6 Proposed 9-storey ST. Proposed 9-storey Blairville Road Mixed-use Building 3.0m 9 Mixed-use Building ST. 3.0m Sheppard Avenue West 21.1m 1.5m 5.5m Minimum 5.5m 668 sq.m. Wilmington Avenue Floorplate 6 12 ST. 11 ST. Wilmington Avenue 22.0m ST. 10 Planned ROW 3.0m ST. 3.0m 2.7m Road Widening 36.0 m Cocksfield Avenue 3.0m 2.7m 32.4m Sheppard Avenue West Southwest View ADDRESS 824 Sheppard Avenue West, 177,Notes: 179 & 181 Cocksfield Avenue SITE GROSS CONSTRUCTION GROSS FLOOR AREA: SHEPPARD FRONTAGE COCKSFIELD FRONTAGE DENSITY: SITE AREA 51,296 SF | ± 1.19 Acres -Ground floor height= 4.5m AREA: AREA: (95% of GCA) MAX HEIGHT: MAX HEIGHT: (Lot Area Excludes Road Widening) BUILDING SIZE 15,500 SF -Residential floor height= 3.0m 4,705sq.m. [approx.] 21,750sq.m. [approx.] 20,660sq.m. [approx.] 12ST/39.5m 6ST/19.5mFRONTAGE 4.39FSI106 Ft on Sheppard Avenue; 151-Ground Ft on Cocksfield floor GFA =Avenue 3,022sq.m. -

Keele Street Avenue Study

KEELE STREET AVENUE STUDY (Sean_Marshall, 2008) by Daniel Hahn Bachelor of Arts, University of Toronto, 2014 A major research project presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Planning in Urban Development. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Daniel Hahn 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A MRP I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. DEDICATION Supported by: my loving and supportive parents and siblings. To: Professor Keeble, a friend and mentor. For: myself. There are three things extremely hard: steel, a diamond, and to know one’s self. II INTRODUCTION/ABSTRACT From its humble origins as a rural country road to its present form as a suburban arterial, the Keele Street Corridor - stretching from Wilson Avenue to Grandravine Drive - has long served the transportation and day-to-day needs of North York and Toronto residents. The following study presents the corridor as it was, as it is, and as it could be. Through a series of recommendations, this report intends to offer a vision of the corridor as an urbanized, livable, and beautiful corridor in keeping with the Official Plan’s Avenues policies and based on the following principles: Locating new and denser housing types that encourage a mix of use, make efficient use of lands, frame the right-of-way, are appropriately massed and attractively designed. -

Queen Street West Planning Study (Bathurst Street to Roncesvalles Avenue) – Official Plan Amendment – Final Report

REPORT FOR ACTION Queen Street West Planning Study (Bathurst Street to Roncesvalles Avenue) – Official Plan Amendment – Final Report Date: February 25, 2020 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Community Planning, Toronto and East York District Wards: Ward 4 - Parkdale-High Park Ward 9 - Davenport Ward 10 - Spadina-Fort York Planning Application Number: 14 163492 STE 14 OZ SUMMARY On November 18, 2013, City Council requested the Chief Planner and Executive Director, City Planning Division to undertake a planning study of Queen Street West between Bathurst Street and Roncesvalles Avenue. This report summarizes the outcome of the study, recommends amendments to the City’s Official Plan in the form of a Site and Area Specific Policy to guide development and public initiatives in the study area, and requests direction regarding additional implementation measures. The proposed policies are intended to allow opportunities for contextually appropriate growth and change, conserve and enhance historic and culturally significant attributes of Queen Street West, guide public and private investment in public spaces, and encourage sustainable choices in new buildings and additions. The proposed amendments align with the recommendations of the West Queen West Heritage Conservation District Study, and the emerging direction for the West Queen West and Parkdale Main Street Heritage Conservation District Plans, which are under development and will be presented to the Toronto Preservation Board and City Council in Q3 2020. A multiple