Concerto for Trumpet in E-Flat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

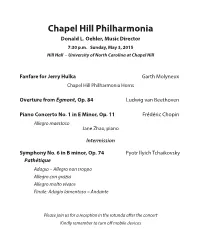

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL´S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF BEETHOVEN´S SYMPHONY NO. 2, OP. 36: A COMPARISON OF THE SOLO PIANO AND THE PIANO QUARTET VERSIONS Aram Kim, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor Gustavo Romero, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair, Division of Keyboard Studies John Murphy, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kim, Aram. Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Transcriptions of Beethoven´s Symphony No. 2, Op. 36: A Comparison of the Solo Piano and the Piano Quartet Versions. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2012, 30 pp., 2 figures, 13 musical examples, references, 19 titles. Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a noted Austrian composer and piano virtuoso who not only wrote substantially for the instrument, but also transcribed a series of important orchestral pieces. Among them are two transcriptions of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36- the first a version for piano solo and the second a work for piano quartet, with flute substituting for the traditional viola part. This study will examine Hummel’s treatment of the symphony in both transcriptions, looking at a variety of pianistic devices in the solo piano version and his particular instrumentation choices in the quartet version. Each of these transcriptions can serve a particular purpose for performers. The solo piano version is an obvious virtuoso vehicle, whereas the quartet version can be a refreshing program alternative in a piano quartet concert. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

THROUGH LIFE and LOVE Richard Strauss

THROUGH LIFE AND LOVE Richard Strauss Louise Alder soprano Joseph Middleton piano Richard Strauss (1864-1949) THROUGH LIFE AND LOVE Youth: Das Mädchen 1 Nichts 1.40 Motherhood: Mutterschaft 2 Leises Lied 3.13 16 Muttertänderlei 2.27 3 Ständchen 2.42 17 Meinem Kinde 2.52 4 Schlagende Herzen 2.29 5 Heimliche Aufforderung 3.16 Loss: Verlust 18 Die Nacht 3.02 Longing: Sehnsucht 19 Befreit 4.54 6 Sehnsucht 4.27 20 Ruhe, meine Seele! 3.54 7 Waldseligkeit 2.54 8 Ach was Kummer, Qual und Schmerzen 2.04 Release: Befreiung 9 Breit’ über mein Haupt 1.47 21 Zueignung 1.49 Passions: Leidenschaft 22 Weihnachtsgefühl 2.26 10 Wie sollten wir geheim sie halten 1.54 23 Allerseelen 3.22 11 Das Rosenband 3.15 12 Ich schwebe 2.03 Total time 64.48 Partnership: Liebe Louise Alder soprano 13 Nachtgang 3.01 Joseph Middleton piano 14 Einerlei 2.53 15 Rote Rosen 2.19 2 Singing Strauss Coming from a household filled with lush baroque music as a child, I found Strauss a little later in my musical journey and vividly remember how hard I fell in love with a recording of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf singing Vier Letze Lieder, aged about 16. I couldn’t believe from the beginning of the first song it could possibly get any more ecstatic and full of emotion, and yet it did. It was a short step from there to Strauss opera for me, and with the birth of YouTube I sat until the early hours of many a morning in my tiny room at Edinburgh University, listening to, watching and obsessing over Der Rosenkavalier’s final trio and presentation of the rose. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

HUMMEL Mozart’S Symphonies Nos

HUMMEL Mozart’s Symphonies Nos. 38 ‘Prague’, 39 and 40 Arranged for Flute, Violin, Cello and Piano Uwe Grodd • Friedemann Eichhorn Martin Rummel • Roland Krüger Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) his privy council, after acceding to the throne in 1775, was pirated copies of his original manuscripts were always a Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) that of poet, artist and politician Johann Wolfgang von threat. Hummel was suspicious of editions published on the Goethe. The court theatre immediately became the central continent. In a letter to a friend he wrote: “How come … Mozartʼs Symphonies Nos. 38 ʻPragueʼ, 39 and 40 focus of city life and the addition of the new Hoftheater in you do not find a single note from an honourable German arranged by Hummel for flute, violin, cello and piano 1791 ensured the predominance of music. Hummelʼs publisher?” The editions for this recording were made using dedication of his arrangement of the Prague Symphony Hummelʼs English publications from Chappell and Co In 1786, at the age of eight, Hummel went to live and study aus dem Serail. Hummelʼs lack of diplomacy, however, reads “This Symphony is respectfully dedicated to His (1823-4) for which J. R. Schultz acted as intermediary in with Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in Vienna. During his two combined with his disregard of dress codes, “loud and Excellency Baron von Goethe, Minister of State to His London. While England and France had regulations years as a lodger in the familyʼs apartment in the pushy” manner and devotion to his own performing career Royal Highness the Grand Duke of Saxe Weimar by J. -

A Performer's Guide to Multimedia Compositions for Clarinet and Visuals: a Tutorial Focusing on Works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 A performer's guide to multimedia compositions for clarinet and visuals: a tutorial focusing on works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O. Smith, and Reynold Weidenaar. Mary Alice Druhan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Druhan, Mary Alice, "A performer's guide to multimedia compositions for clarinet and visuals: a tutorial focusing on works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O. Smith, and Reynold Weidenaar." (2003). LSU Major Papers. 36. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/36 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO MULTIMEDIA COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINET AND VISUALS: A TUTORIAL FOCUSING ON WORKS BY JOEL CHADABE, MERRILL ELLIS, WILLIAM O. SMITH, AND REYNOLD WEIDENAAR A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Mary Alice Druhan B.M., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.M., University of Cincinnati -

An Examination of George Frideric Handel's “Let

AN EXAMINATION OF GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL’S “LET THE BRIGHT SERAPHIM” FROM SAMSON, FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN’S CONCERTO FOR TRUMPET IN E FLAT MAJOR, KARL JENKINS’ SALM O DEWI SANT, AND ERIK MORALES’ CONCERTO FOR TRUMPET IN C AND PIANO by PAUL MARTIN MUELLER B.M., Grand Valley State University, 2007 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2009 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Gary Mortenson Abstract This Master‟s report contains biographical, historical, and theoretical analysis as well as stylistic and technical considerations for the four works performed for the author‟s Master‟s recital on April 29th, 2009. The works are Handel‟s aria “Let the Bright Seraphim” from Samson, Franz Joseph Haydn‟s Concerto for Trumpet in E Flat Major, Karl Jenkins‟s Salm o Dewi Sant, and Erik Morales‟s Concerto for Trumpet in C and Piano. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. v List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi CHAPTER 1 - “Let the Bright Seraphim” From Samson............................................................... 1 Brief Biography of George Frederic Handel .............................................................................. 1 The Creation and Performance of Samson ................................................................................