Information Processing Among High School Hispanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

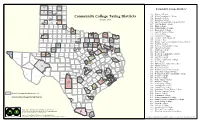

Community College Taxing Districts, January 2017

169 SHERMAN HANSFORD 169 LIPSCOMB DALLAM OCHILTREE Community College Districts* HUTCHINSON 169 164 HEMPHILL ROBERTS HARTLEY MOORE 169 162 - Alamo Colleges 163 - Alvin Community College OLDHAM Community College Taxing Districts POTTER CARSON 173 WHEELER GRAY 164 - Amarillo College 164 January 2017 DEAF 165 - Angelina College SMITH ARMSTRONG 173 COLLINGS 166 - Austin Community College District 164 RANDALL WORTH DONLEY 167 - Coastal Bend College HALL 168 - Blinn College PARMER CASTRO SWISHER BRISCOE 173 CHILDRESS 169 - Frank Phillips College HARDEMAN 170 - Brazosport College BAILEY LAMB HALE FLOYD MOTLEY COTTLE 207 WICHITA 171 - Central Texas College FOARD WILBARGER COCHRAN CLAY 172 - Cisco College 195 RED RIVER KING FANNIN LAMAR 198 LUBBOCK CROSBY DICKENS KNOX BAYLOR ARCHER 190 180 173 - Clarendon College MONTAGUE COOKE GRAYSON 203 HOCKLEY DELTA BOWIE TITUS 174 - College of the Mainland JACK 175 - Collin College YOAKUM KENT STONEWALL THROCK- YOUNG 209 DENTON 175 HUNT 192 TERRY LYNN GARZA HASKELL HOPKINS CASS MORRIS MORTON WISE COLLIN FRANKLIN 176 - Dallas County Community College District 190 CAMP ROCKWALL RAINS WOOD MARION 177 - Del Mar College UPSHUR GAINES PALO 209 201 176 DAWSON BORDEN 210 FISHER JONES SHACKEL- STEPHENS PINTO PARKER TARRANT DALLAS 178 - El Paso Community College SCURRY FORD KAUFMAN HARRISON VAN GREGG JOHNSON 205 ZANDT 206 179 - Galveston College 196 HOOD ELLIS ANDREWS 172 184 MARTIN 183 MITCHELL NOLAN TAYLOR CALLAHAN 181 SMITH 180 - Grayson College ERATH SOMERVELL HENDERSON RUSK 194 HOWARD PANOLA EASTLAND 181 - Hill -

IPEDS Data Feedback Report 2017

Image description. Cover Image End of image description. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS What Is IPEDS? The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is a system of survey components that collects data from about 7,000 institutions that provide postsecondary education across the United States. IPEDS collects institution-level data on student enrollment, graduation rates, student charges, program completions, faculty, staff, and finances. These data are used at the federal and state level for policy analysis and development; at the institutional level for benchmarking and peer analysis; and by students and parents, through the College Navigator (http://collegenavigator.ed.gov), an online tool to aid in the college search process. For more information about IPEDS, see http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. What Is the Purpose of This Report? The Data Feedback Report is intended to provide institutions a context for examining the data they submitted to IPEDS. The purpose of this report is to provide institutional executives a useful resource and to help improve the quality and comparability of IPEDS data. What Is in This Report? As suggested by the IPEDS Technical Review Panel, the figures in this report provide selected indicators for your institution and a comparison group of institutions. The figures are based on data collected during the 2016-17 IPEDS collection cycle and are the most recent data available. This report provides a list of pre-selected comparison group institutions and the criteria used for their selection. Additional information about these indicators and the pre- selected comparison group are provided in the Methodological Notes at the end of the report. -

Khkx(Fm), Kqrx(Fm), Kmcm(Fm) Eeo Public File Report I. Vacancy List

KHKX(FM), KQRX(FM), KMCM(FM) EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2018 - March 31, 2019 I. VACANCY LIST See Master Recruitment Source List (MRSL) for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources (RS) used to RS Referring Job Title fill vacancy Hiree SALES EXECUTIVE 2,5,10,25,26 26 SALES EXECUTIVE 2,5,10,21,22,25 10 SALES EXECUTIVE 2,14, 25, 26 14 SALES EXECUTIVE 2,5,10,13,21,22,23,24,25,26 13 KHKX(FM), KQRX(FM), KMCM(FM) EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2018 - March 31, 2019 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST (MRSL) RS RS Information Source Entitled to No. of Interviewees Number Vacancy Notification? Referred by RS over (Yes/No) 12-month period Texas Workforce Commission 1 3510 N Ave A Midland, Texas 79711 No 0 (432)687-3003 www.twc.state.tx.us Texas Association of Broadcasters 2 502 E. 11th Street Ste 200 Austin, Tx 78701 No 0 (512)322-9944 www.tab.org Odessa American - Classifieds 3 222 E. 4th Street Odessa, Tx 79761 No 0 (432)333-7777 www.oaoa.com Midland Reporter Telegram - Classified Dept 201 E. Illinois Midland, Tx 79701 4 No 0 (432)682-5311 www.mywesttexas.com All Access Radio Site 5 28955 Pacific Coast Highway Ste 210 No 1 Malibu, CA 90265 (310)457-8058 (F) www.allaccess.com Midland College 6 3600 N. Garfield Midland, Tx 79705 No 0 (432)685-4764 www.midlland.edu University of Texas of Permian Basin 7 4901 E. University Odessa, Tx 79762 No 0 (432)522-2633 www.utpb.edu Odessa College - Gloria Rangel 8 201 W. -

ACCD - Northwest Vista College Academic

TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Page 1 AUTOMATED STUDENT AND ADULT LEARNER FOLLOW-UP SYSTEM 2001 - 2002 STUDENTS PURSUING ADDITIONAL EDUCATION - BY INSTITUTION (Graduates, Completers and Non-Returners) FORMER COMMUNITY OR TECHNICAL COLLEGE NAME: STUDENT TYPE: ACCD - Northwest Vista College Academic Community & Technical Colleges Attended, Fall 2002 Number of Students: ACCD - Northwest Vista College 4 ACCD - Palo Alto College 58 ACCD - San Antonio College 195 ACCD - St. Philip's College 60 Alvin Community College 1 Austin Community College 15 Blinn College 20 Cisco Junior College 2 Coastal Bend College 2 College of the Mainland 1 Collin County Community College District 2 DCCCD - Brookhaven College 1 DCCCD - Eastfield College 1 DCCCD - North Lake College 1 Del Mar College 5 El Paso Community College District 3 Houston Community College System 2 Kilgore College 1 Lamar - Institute of Technology 1 Laredo Community College 3 McLennan Community College 1 Midland College 2 NHMCCD - Cy-Fair College 1 NHMCCD - Montgomery College 1 NHMCCD - Tomball College 1 North Central Texas College 1 Odessa College 1 San Jacinto College - Central Campus 2 South Plains College 2 South Texas Community College 2 Southwest Texas Junior College 6 Tarrant County College District - Southeast Campus 1 Texas Southmost College 5 Vernon College 1 Victoria College, The 1 Subtotal - Community and Technical Colleges 406 Universities Attended, Fall 2002 Number of Students: Angelo State University 13 Lamar University 1 Prairie View A&M University 4 Sam Houston State -

Community Colleges

TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Public Community Colleges TUITION AND FEES DATA from IFRS The tuition and fee data reported on the following pages reflects the average amounts charged to resident undergraduate students enrolled in exactly 15 semester credit hours (SCH) at Texas public community colleges. Amounts reported include statutory tuition, average mandatory fees and average college course fees. A student's actual charges may vary based on the student's type and level of enrollment, the student's specific personal circumstances, or for other reasons deemed appropriate by the institution. FOOTNOTES: * All data was reported under definitions for tuition and fees adopted January 2006 by the Coordinating Board. (1) Alamo Community College District reports all colleges under it including San Antonio College (2) Lone Star College System was formerly North Harris-Montgomery Community College Note: The Total Academic Charges column is the sum of Statutory Tuition + Designated Tuition + Mandatory Fees + Avg Coll and Course Fees for each school. The bottom of the column is the average (excluding zeroes, if any) of the Total Academic Charges of each school. Community Colleges T&F (IFRS Fall 03 thru Fall 17) 02.05.2018 a.xlsx 1 of 13 Footnotes 2/5/2019 Resident Undergraduates ACADEMIC CHARGES at Texas Public Change from Fall 2003 to Fall 2017 Universities (15 SCH) Institution Fall 2003 Fall 2004 Fall 2005 Fall 2006 Fall 2007 Fall 2008 Fall 2009 Fall 2010 Fall 2011 Alamo Community College District $658 $723 $760 $812 $850 $925 $944 -

Kchx Fm, Kcrs-Am, Kcrs-Fm, Kfzx Fm, Kmrk Fm Eeo Public File Report I. Vacancy List

KCHX FM, KCRS-AM, KCRS-FM, KFZX FM, KMRK FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2020 thru March 31, 2021 (Note: 12-month period determined by FCC license renewal filing date and not on calendar basis) I. VACANCY LIST See Master Recruitment Source List (MRSL) for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources (RS) Used to RS Referring Job Title Fill Vacancy Hiree [Insert name of job title, e.g. Account Executive] [Insert numbers corresponding to RS’s in [Insert number the MRSL, e.g., 1-10, 15, 18-23] corresponding to RS in the MRSL, e.g., 23] Traffic Director 1 - 16 11 Program Director 1 - 16 4 See “II. Master Recruitment Source List” for recruitment sources source data KCHX FM, KCRS-AM, KCRS-FM, KFZX FM, KMRK FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT April 1, 2020 thru March 31, 2021 (Note: 12-month period determined by FCC license renewal filing date and not on calendar basis) II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST (MRSL) No. of Source Entitled Interviewees to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Notification? RS Number (Yes/No) over 12-month period 1 Job Search Office Y 0 Texas Workforce Commission 2626 JBS Parkway Bldg. D Odessa, TX 79761 2 Midland Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Y 0 208 S. Marienfeld Midland, TX 79701 3 Lauren Henson Y 0 Career Center Odessa College 201 W. University Odessa, TX 79764 4 Texas Association of Broadcaster Y 0 502 E. 11th St. Suite 200 Austin, TX 79701-2619 5 All Access Music Group Y 0 1222 16th Avenue South, Suite 25 Nashville, TN 37212 6 Midland College Y 0 Connie Howard 3600 N. -

Student Success Online Resume For

Online Resume for Legislators and Other Policymakers ALVIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE Location: Alvin, Gulf Coast Region Medium Accountability Peer Group: Angelina College, Brazosport College, Cisco College, Coastal Bend College, College of The Mainland, Grayson County College, Hill College, Kilgore College, Lee College, McLennan Community College, Midland College, Odessa College, Paris Junior College, Southwest Texas Junior College, Temple College, Texarkana College, Texas Southmost College, Trinity Valley Community College, Victoria College, Weatherford College, Wharton County Junior College Degrees Offered: Associate's, Advanced Technology Certificate, Certificate 1, Certificate 2, Enhanced Skills Certificate Institutional Resumes Accountability System Definitions Institution Home Page Enrollment Funding Fall 2010 Fall 2014 Fall 2015 FY 2010 Pct of FY 2014 Pct of FY 2015 Pct of Source Amount Total Amount Total Amount Total Race/Ethnicity Number Percent Number Percent Number Percent Appropriated Funds $11,444,589 30.8% $11,042,577 32.4% $10,976,984 26.8% White 3,323 58.1% 2,516 51.2% 2,488 48.6% Federal Funds $4,901,785 13.2% $4,874,210 14.3% $4,527,064 11.0% Hispanic 1,444 25.2% 1,498 30.5% 1,613 31.5% Tuition & Fees $7,872,150 21.2% $10,252,689 30.1% $10,107,379 24.6% African-American 569 9.9% 518 10.5% 603 11.8% Total Revenue $37,198,139 100.0% $34,101,989 100.0% $41,010,803 100.0% Asian/Pacific Isl. 256 4.5% 267 5.4% 273 5.3% Other 129 2.3% 115 2.3% 139 2.7% Tax Rate per $100 Total 5,721 100.0% 4,914 100.0% 5,116 100.0% Taxable Property -

2020-2021 College and Career Planning Guide

2020-2021 COLLEGE AND CAREER PLANNING GUIDE ABELL JR. HIGH ALAMO JR. HIGH GODDARD JR. HIGH SAN JACINTO JR. HIGH 432-689-6200 432-689-1700 432-689-1300 432-689-1350 LEE FRESHMAN HIGH SCHOOL MIDLAND FRESHMAN HIGH SCHOOL 432-689-1250 432-689-1200 ROBERT E LEE COLEMAN EARLY COLLEGE MIDLAND HIGH SCHOOL HIGH SCHOOL HIGH SCHOOL @ MC HIGH SCHOOL 432-689-1600 432-689-5000 432-685-4641 432-689-1100 www.midlandisd.net 432-240-1000 This page intentionally left blank MIDLAND INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT 2019-2020 BOARD OF TRUSTEES Rick Davis President Tommy Bishop Vice President James E. Fuller Secretary Bryan Murry Trustee John Trischitti Trustee John Kennedy Trustee Robert Marquez Trustee CENTRAL ADMINISTRATION Mr. Orlando Riddick Superintendent James Riggen, AIA Chief Operations Officer Darla Moss Chief Financial Officer Patrick Jones Chief Academic Officer CAMPUS ADMINISTRATORS AND COUNSELORS MIDLAND HIGH SCHOOL LEE HIGH SCHOOL 906 W. Illinois 3500 Neely Midland, Texas 79701 Midland, Texas 79707 (432) 689-1100 (432) 689-1600 Dr. Leslie Sparacello Principal Stan VanHoozer Principal Misty Ring Associate Principal Vanessa Carr Associate Principal Instructional Services Director Jennifer Jones Instructional Services Director Kerry Hoover Counselor Heather Clark Counselor Molly Marcum Counselor Michelle Barrandey Counselor Nicole Phillips Counselor Marricar Morris Counselor Rachelle Taylor Counselor Latisha Hermosillo Counselor Steffie Senter Counselor Stephanie Chrane Counselor David Haley Counselor LaLena Carpenter Counselor COLEMAN HIGH SCHOOL EARLY COLLEGE HIGH SCHOOL @ MC 1600 E. Golf Course 3600 N. Garfield Midland, Texas 79701 Midland, Texas 79705 (432) 689-5000 (432) 685-4641 David Moore Principal Renee Aldrin Principal K’Lynn Roberts Assistant Principal Rene Barrientes Assistant Principal Taylor Savas Counselor Tammy Dennison Counselor ADVANCE TECHNOLOGY CENTER (ATC) 3200 W. -

Midland College General Catalog 2003-2004

MIDLAND COLLEGE GENERAL CATALOG 2003-2004 VOLUME XXXI ACCREDITATION Midland College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097: Telephone number 404-679-4501) to award associate degrees and certificates. Midland College meets all guidelines and standards as set forth by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. Midland College is accredited by the following: Allied Health Information Management Association American Veterinary Medical Association Board of Vocational Nurse Examiners for the State of Texas Board of Nurse Examiners for the State of Texas Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Educational Programs Committee on Accreditation for Respiratory Care Federal Aviation Administration Joint Review Committee on Education in Radiologic Technology National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission Texas Certification Board of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse Texas Department of Health Documentation may be viewed in the President’s office at: Address: Telephones: Midland College (432) 685-4500 3600 North Garfield (432) 570-8805 Midland, Texas 79705 (432) 570-8875 www.midland.edu This institution is in compliance with the Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. YOUR COLLEGE . 3 2. CALENDAR . 24 3. STUDENT ADVISING AND ADMISSIONS . 32 4. FEE SCHEDULE INFORMATION . 39 5. SERVICES FOR STUDENTS . 44 6. STUDENT ACTIVITIES . 53 7. CONTINUING EDUCATION . 54 8. ADULT BASIC EDUCATION . 55 9. FINANCIAL AID . 60 10. STUDENT ACADEMIC INFORMATION . 67 11. TRANSFER INFORMATION . 71 12. DEGREE INFORMATION . 74 13. DEGREE PLANS & COURSE DESCRIPTIONS . 79 14. INDEX . 242 CATALOG RIGHTS This catalog is effective for the 2003-2004 academic school year. -

Volleyball-Media-Guide-2011.Pdf

2011 Roster No. Name Pos. Ht. Yr. Hometown / Previous School 1 Sarah Gillis DS/L 5-6 Soph. Dripping Springs / Dripping Springs HS (Northwestern State) 2 Rachel Tower OH/S 6-1 Soph. Kingwood / Kingwood HS 3 Jazmine Green OH 5-10 Soph. Houston / Cypress Falls HS 4 Krista Koopmann RS 6-1 Fresh. China Spring / China Spring HS 5 Kanoe Pupuhi S 5-4 Fresh. Kahalu’u, Hawaii / Roosevelt HS 6 Victoria Orscheln DS/L 5-9 Fresh. Austin / Lake Travis HS 7 Marie-Pierre Bakima OH 5-9 Fresh. Nogent-sur-Oise, France / Lycee Emmanuel Mounier 8 Hayley Couch DS/L 5-7 Soph. Santa Fe / Santa Fe HS (Galveston College) 9 Marlaina Pleydle MB 5-9 Fresh. Victorville, Calif. / Victor Valley HS 10 Shelbee Pier MB/OH 6-1 Fresh. Huffman / Huffman HS 11 Jordyn Monk MB 5-11 Fresh. Mont Belvieu / Barbers Hill HS 13 Bria Bell MB 6-0 Fresh. Waco / Midway HS 14 Julia Menhart DS/S 5-9 Fresh. Hormannsberg, Germany 15 Kayla Nowaski RS 5-9 Soph. Houston / Spring HS (Galveston College) 2 San Jacinto College Volleyball 2011 Player Profiles #1 Sarah Gillis 5-6 | Sophomore | DS/L #2 Rachel Tower Dripping Springs | Dripping 6-1 | Sophomore | OH Springs HS (Northwestern State) Kingwood | Kingwood HS Prior to San Jac: Played a year at Northwestern State University… A As a freshman: Averaged 1.45 kills per set and just under .50 blocks per set. 2010 graduate of Dripping Springs HS… Team MVP as a senior… First- Prior to San Jac: A 2010 graduate of Kingwood HS… Led the Mustangs to team All-District selection as a junior… Led the Tigers to three district the district championship (2009-2010), and the third round of the playoffs championships… Played club for Austin Juniors. -

The Feasibility of Expanding Texas' Community College Baccalaureate

The Feasibility of Expanding Texas’ Community College Baccalaureate Programs A Report to the 81st Texas Legislature October 2010 Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Fred W. Heldenfels IV, CHAIR Austin Elaine Mendoza, VICE CHAIR San Antonio Joe B. Hinton, SECRETARY Crawford Durga D. Argawal Houston Dennis D. Golden Carthage Harold Hahn El Paso Wallace Hall Dallas Lyn Bracewell Phillips Bastrop A.W. “Whit” Riter Tyler Eric Rohne, STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE Corpus Christi Raymund A. Paredes, COMMISSIONER OF HIGHER EDUCATION Mission of the Coordinating Board The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s mission is to work with the Legislature, Governor, governing boards, higher education institutions and other entities to help Texas meet the goals of the state’s higher education plan, Closing the Gaps by 2015, and thereby provide the people of Texas the widest access to higher education of the highest quality in the most efficient manner. Philosophy of the Coordinating Board The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board will promote access to quality higher education across the state with the conviction that access without quality is mediocrity and that quality without access is unacceptable. The Board will be open, ethical, responsive, and committed to public service. The Board will approach its work with a sense of purpose and responsibility to the people of Texas and is committed to the best use of public monies. The Coordinating Board will engage in actions that add value to Texas and to higher education. The agency will avoid efforts that do not add value or that are duplicated by other entities. -

Institutional Resumes Accountability System Definitions Institution Home Page

Online Resume for Prospective Students, Parents and the Public MCLENNAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE Location: Waco, Central Region Medium Accountability Peer Group: Alvin Community College, Angelina College, Brazosport College, Cisco College, Coastal Bend College, College of The Mainland, Grayson County College, Hill College, Kilgore College, Lee College, Midland College, Odessa College, Paris Junior College, Southwest Texas Junior College, Temple College, Texarkana College, Texas Southmost College, Trinity Valley Community College, Victoria College, Weatherford College, Wharton County Junior College Degrees Offered: Associate's, Advanced Technology Certificate, Certificate 1, Certificate 2, Enhanced Skills Certificate Institutional Resumes Accountability System Definitions Institution Home Page Enrollment Costs Institution Peer Group Avg. Average Annual Total Academic Costs for Resident Race/Ethnicity Fall 2016 % Total Fall 2016 % Total Undergraduate Student Taking 30 SCH, FY 2017 White 4,588 52.4% 2,498 46.4% Peer Group Hispanic 2,615 29.8% 1,992 37.0% Type of Cost Institution Average African American 1,189 13.6% 560 10.4% Asian/Pacific Isl. 128 1.5% 117 2.2% In-district Total Academic Cost $3,450 $2,582 International 0 .0% 34 .6% Out-of-district Total Academic Cost $3,990 $4,010 Other & Unknown 244 2.8% 183 3.4% Off-campus Room & Board $7,065 $7,079 Total 8,764 100.0% 5,387 100.0% Cost of Books & Supplies $1,260 $1,531 Cost of Off-campus Transportation $4,392 $4,291 Financial Aid and Personal Expenses Total In-district Cost $16,167 $15,483 Institution