The Feasibility of Expanding Texas' Community College Baccalaureate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

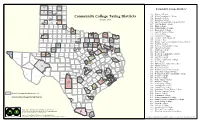

Community College Taxing Districts, January 2017

169 SHERMAN HANSFORD 169 LIPSCOMB DALLAM OCHILTREE Community College Districts* HUTCHINSON 169 164 HEMPHILL ROBERTS HARTLEY MOORE 169 162 - Alamo Colleges 163 - Alvin Community College OLDHAM Community College Taxing Districts POTTER CARSON 173 WHEELER GRAY 164 - Amarillo College 164 January 2017 DEAF 165 - Angelina College SMITH ARMSTRONG 173 COLLINGS 166 - Austin Community College District 164 RANDALL WORTH DONLEY 167 - Coastal Bend College HALL 168 - Blinn College PARMER CASTRO SWISHER BRISCOE 173 CHILDRESS 169 - Frank Phillips College HARDEMAN 170 - Brazosport College BAILEY LAMB HALE FLOYD MOTLEY COTTLE 207 WICHITA 171 - Central Texas College FOARD WILBARGER COCHRAN CLAY 172 - Cisco College 195 RED RIVER KING FANNIN LAMAR 198 LUBBOCK CROSBY DICKENS KNOX BAYLOR ARCHER 190 180 173 - Clarendon College MONTAGUE COOKE GRAYSON 203 HOCKLEY DELTA BOWIE TITUS 174 - College of the Mainland JACK 175 - Collin College YOAKUM KENT STONEWALL THROCK- YOUNG 209 DENTON 175 HUNT 192 TERRY LYNN GARZA HASKELL HOPKINS CASS MORRIS MORTON WISE COLLIN FRANKLIN 176 - Dallas County Community College District 190 CAMP ROCKWALL RAINS WOOD MARION 177 - Del Mar College UPSHUR GAINES PALO 209 201 176 DAWSON BORDEN 210 FISHER JONES SHACKEL- STEPHENS PINTO PARKER TARRANT DALLAS 178 - El Paso Community College SCURRY FORD KAUFMAN HARRISON VAN GREGG JOHNSON 205 ZANDT 206 179 - Galveston College 196 HOOD ELLIS ANDREWS 172 184 MARTIN 183 MITCHELL NOLAN TAYLOR CALLAHAN 181 SMITH 180 - Grayson College ERATH SOMERVELL HENDERSON RUSK 194 HOWARD PANOLA EASTLAND 181 - Hill -

Eric T. Lundin

Eric T. Lundin Address: 24122 Blue Crest Dr., Porter, TX, 77365 Cell: (281) 467-2165| [email protected] Attorney- Bar #: 24102120 EDUCATION South Texas College of Law Houston, Houston, TX Doctor of Jurisprudence, May 2016. Honors: Deans List Scholar, Phi Delta Phi Honors Fraternity, CALI recipient, Top 1/3 of class. University of Houston, C. T. Bauer College of Business, Houston, TX Master of Business Administration, May 2013. Honors: Discover Leadership’s 2012 Top Leaders American Military University, Charleston, WV Master of Arts (Political Science), February 2010. Honors: Golden Key Honors Society for Excellence Trinity University, San Antonio, TX Bachelor of Arts, Psychology and Drama, May 2004 ATTORNEY EXPERIENCE Wojciechowski & Associates. (Attorney) (2018-Present) • Handle all aspects of Insurance Defense, Construction Law, and Civil Litigation. Greer, Scott & Shropshire, LLP. (Associate Attorney) (2018) • Handle all aspects of Insurance Defense, Personal Injury, and Civil Litigation. Lundin Law Office. (Principal Attorney) (2016-Present) • Practicing in all aspects of law in the Hospitality, Creative, Tourism, Business, Education, and Service Industries. Eisen Law Firm. (Contract Attorney) (2017-2018) • Handle all aspects of Commercial Litigation, creditors rights, bankruptcy, Business law, and general civil matters. Lakewood Church, Houston Texas (Legal Intern) • Assisted the general counsel by researching and writing on important legal issues. Harris County District Attorney’s Office, Houston Texas (Legal Intern) • Assisted -

IPEDS Data Feedback Report 2017

Image description. Cover Image End of image description. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS What Is IPEDS? The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is a system of survey components that collects data from about 7,000 institutions that provide postsecondary education across the United States. IPEDS collects institution-level data on student enrollment, graduation rates, student charges, program completions, faculty, staff, and finances. These data are used at the federal and state level for policy analysis and development; at the institutional level for benchmarking and peer analysis; and by students and parents, through the College Navigator (http://collegenavigator.ed.gov), an online tool to aid in the college search process. For more information about IPEDS, see http://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. What Is the Purpose of This Report? The Data Feedback Report is intended to provide institutions a context for examining the data they submitted to IPEDS. The purpose of this report is to provide institutional executives a useful resource and to help improve the quality and comparability of IPEDS data. What Is in This Report? As suggested by the IPEDS Technical Review Panel, the figures in this report provide selected indicators for your institution and a comparison group of institutions. The figures are based on data collected during the 2016-17 IPEDS collection cycle and are the most recent data available. This report provides a list of pre-selected comparison group institutions and the criteria used for their selection. Additional information about these indicators and the pre- selected comparison group are provided in the Methodological Notes at the end of the report. -

Institutional Resumes Accountability System Definitions Institution Home Page

Online Resume for Prospective Students, Parents and the Public CISCO COLLEGE Location: Cisco, Northwest Region Medium Accountability Peer Group: Alvin Community College, Angelina College, Brazosport College, Coastal Bend College, College of The Mainland, Grayson County College, Hill College, Kilgore College, Lee College, McLennan Community College, Midland College, Odessa College, Paris Junior College, Southwest Texas Junior College, Temple College, Texarkana College, Texas Southmost College, Trinity Valley Community College, Victoria College, Weatherford College, Wharton County Junior College Degrees Offered: Associate's, Certificate 1, Certificate 2 Institutional Resumes Accountability System Definitions Institution Home Page Enrollment Costs Institution Peer Group Avg. Average Annual Total Academic Costs for Resident Race/Ethnicity Fall 2016 % Total Fall 2016 % Total Undergraduate Student Taking 30 SCH, FY 2017 White 1,990 61.5% 2,498 46.4% Peer Group Hispanic 722 22.3% 1,992 37.0% Type of Cost Institution Average African American 318 9.8% 560 10.4% Asian/Pacific Isl. 78 2.4% 117 2.2% In-district Total Academic Cost $3,810 $2,564 International 37 1.1% 34 .6% Out-of-district Total Academic Cost $4,710 $3,977 Other & Unknown 93 2.9% 183 3.4% Off-campus Room & Board $4,438 $7,204 Total 3,238 100.0% 5,387 100.0% Cost of Books & Supplies $0 $1,591 Cost of Off-campus Transportation $5,776 $4,225 Financial Aid and Personal Expenses Total In-district Cost $14,024 $15,584 Institution Peer Group FY 2015 Percent Ave Amt Percent Avg Amt Total -

Deicla Harlingen

NEWS RELEASE: Contact: Steve Pruett, COO (410) 568-1500 SINCLAIR PROMOTES LINDA GUERRERO DEICLA TO GENERAL MANAGER IN HARLINGEN-WESLACO-BROWNSVILLE-MCALLEN, TX Harlingen, TX (November 16, 2015) – Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) announced that Linda Guerrero Deicla has been promoted to General Manager of KGBT-TV (CBS) in the Harlingen-Weslaco-Brownsville-McAllen, Texas market. The announcement was made by Steve Pruett, Co-Chief Operating Officer of Sinclair’s television group. In making the announcement, Mr. Pruett said, “Linda’s previous positions at KGBT-TV as Business Manager and Media Operations Manager have allowed her to become intimately familiar with the day-to-day operations of the television station, as well as showcase her leadership skills. We congratulate her on her promotion to General Manager.” “It is an honor to serve as General Manager for KGBT-TV, a station with rich history in the Rio Grande Valley, and a station I grew up watching,” commented Ms. Deicla. “I look forward to working with KGBT-TV’s staff and management team in my new role so that we may continue to deliver informative news content to the community and serve as multi-media consultants for our advertisers.” Ms. Deicla joined KGBT-TV in 2004 as Accounting Supervisor and was promoted in 2006 to Business Manager overseeing all of the station’s financial reporting, general accounting functions and HR compliance. She also served as the Media Operations Manager for KGBT-TV, overseeing the engineering, promotions and production departments. Previously, Ms. Deicla worked as a Tax Associate for Arthur Andersen, LLP in San Antonio and as a Staff Accountant for BFI Waste Services of Texas in the Rio Grande Valley. -

University of Houston-Clear Lake Transfer Student GPA Report

University of Houston-Clear Lake Office of Institutional Research University of Houston-Clear Lake transfer student GPA report This report summarizes cumulative GPA information for UHCL transfer students including a summary of those whose last institution attended was an area Gulf Coast Consortium Community College. If variance exists when comparing these figures to other previously published reports, it is important to note that these data were extracted after final grades were submitted and data at the end of term generally decreases compared to the 12'th day census data. Definitions: Gulf Coast Consortium: Consists of Alvin Community College, Blinn College, Brazosport College, College of the Mainland, Galveston College, Houston Community College, Lee College, Lone Star College - North Harris, San Jacinto College 1, Victoria College and Wharton County Junior College. UHCL Undergrad: Gulf Coast Consortium plus all other transfer students. LT 3: Less than 3 (non-zero value ). The data is not displayed to protect confidential information. 0: No students recorded for that major. 1Prior to 2004 and again in Fall 2008 many San Jacinto students were listed as transfers from the Central campus instead of the North and South campuses. In 2008, San Jacinto implemented E (electronic) Transcripting and the three campuses cannot be easily distinguished. For this reason, OIR is now reporting San Jacinto College campuses combined Spring 2012 Cumulative GPA Number Mean College of GPA Students Alvin Community College 307 3.139 Blinn College 14 3.152 -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Four Finalists Named for President's Position

NOVEMBER 2015 Four finalists named for president’s position After reviewing a large pool of qualified candidates, the presidential search committee has named four finalists for the president’s job at Kilgore College. The search committee is comprised of Board Dr. Brenda Kays Dr. Lynn Moore Dr. Mark Smith Dr. Kyle Wagner Secretary Karol Current position: Current position: Current position: Current position: VP of Pruett; Board VP President, Stanly President, Southeast Vice President of Instruction & Economic James Walker; trustee Community College, Kentucky Community & Educational Services at Development, Coastal Joe Carrington and North Carolina Technical College Temple College Bend College, Texas college employees D’Wayne Shaw and Education: Education: Education: Education: Ed.D. from University of Ph.D. from The Univ. of Ph.D. from Capella Ph.D. from Capella Brandon Walker. North Texas in Denton Texas at Austin There will be two University University open forums on each Interview & Interview & Interview & Interview & interview day where Public Forum Date: Public Forum Date: Public Forum Date: Public Forum Date: the public will have Thursday, Nov. 12 Monday, Nov. 16 Tuesday, Nov. 10 Thursday, Nov. 5 an opportunity to ask 1:15-2pm, 2:15-3pm 1:15-2pm, 2:15-3pm 1:15-2pm, 2:15-3pm 1:15-2pm, 2:15-3pm questions. Administration Bldg. Administration Bldg. Administration Bldg. Administration Bldg. Rangers will play for SWJCFC Spradlin dies at age 85 Championship Saturday in Corsicana Kilgore College’s longest- serving board member, R.E. The Kilgore College football “Sonny” Spradlin Jr., passed away team picked off five Trinity Saturday, Oct. 17. -

Complete 2009/2010 Catalog

General Catalog for 2010-2011 Volume 61, No. 2 • August 2010 Alvin Community College is Accredited by: Table of Contents Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Academic Calendar . .2 1866 Southern Lane Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 ACC Phone Directory . .4 Telephone Number:404-679-4501 to award associate degrees and certificates. General Information . .5 Also Approved and Accredited by: Academic Policies & Regulations . .10 Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Texas College and University System Student Services . 36 Member: Educational Programs . 44 American Association of Community and Junior Colleges Course Descriptions . 124 Association of Community College Trustees Gulf Coast Intercollegiate Council Board of Regents, Administration, National Institute for Staff and Organizational Faculty & Staff . .172 Development National Junior College Athletic Association Index & Campus Maps . 179 Region XIV Athletic Conference Texas Community College Teachers Association Texas Association of Community Colleges Alvin Community College is an equal opportunity institution and does ALVIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE not discriminate against anyone on the basis of race, religion, color, 3110 Mustang Road sex, handicap, age, national origin, or veteran status. Alvin, Texas 77511 Phone: 281-756-3500 Financial aid cost of attendance (COA) is calculated on a yearly basis; therefore, adjustments will not be made for changes approved PEARLAND CENTER by the Alvin Community College Board of Regents. 2319 N. Grand Blvd. Pearland, Texas 77581 Any of the regulations, services, or course offerings appearing in Phone:281-756-3787 this catalog may be changed without prior notice. The regulations appearing here will be in force starting with the 2010 fall semester. Interpretation of Catalog The administration of Alvin Community College acts as final interpreter of this catalog and all other college publications. -

Page 1 Minutes Meeting: Tuesday, July 21, 2015, 10:00 Am

Alvin Community College Houston Community College System Brazosport College Lee College Blinn College Lone Star College System College of the Mainland San Jacinto College District Galveston College Wharton County Junior College Minutes Meeting: Tuesday, July 21, 2015, 10:00 am – 1:00pm Hosted by: San Jacinto College 1. Meeting called to order by Michelle Callaway. 15 Attendees: • Alvin: Patrick Sanger & Tammy Braswell • Lee: absent • Brazosport: Cindy Ullrich & Scott • Lone Star College: Kent McShan, Janet Furtwengler Flores, Jacqueline Goff & Deseree Probasco • Blinn: absent • San Jacinto: George Gonzalez, Marco • College of the Mainland: Amber Lummus, & Lozano, Joe Schlichting, Maria Gallegos & Sarah Flores Michelle Callaway • Galveston: JoAnn Buentello & Larry Root • Wharton County: absent • Houston: Raymond Golitko 2. May 13, 2014 minutes were approved. 3. Old Business a. Gainful Employment: Mostly, Financial Aid offices are taking care of this request. Members were requested to continue with the project and send in Fall 2013 and Fall 2014 data. The requested data begins with Fall 2008. b. GCAIR Retention and Success Project: (Fall 2014 Update), please send in Fall 2013 and Fall 2014 data. c. GCAIR Member Directory: Please update your one-page directory information (Fall 2014 Update) if not already completed. 4. New Business: a. Member Directory: Brazosport updates on website b. TAIR in Clear Lake (Feb. 27 through March 2, 2017): This information was in the TAIR newsletter. NASA Hilton in Clear Lake. Cindy Ullrich suggested GCAIR members volunteer to assist with the TAIR conference. c. GCIAR Listserv Options: President-elect manages. GCAIR account is set up on Google for GCAIR listserv group. Michelle Calloway sent email invitation for members to subscribe to the GCAIR google group. -

TSI Testing Sites

TSI Testing Sites Institution Name Site Name City Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Abilene Sul Ross State University Sul Ross State University Testing Services Alpine Amarillo College Amarillo College - Testing Services Amarillo Aransas Pass High School Aransas Pass High School Aransas Pass University of Texas at Arlington UTA Testing Services Arlington Trinity Valley Community College Trinity Valley Community College Athens Austin Community College 03.Eastview Campus-ACC Austin Austin Community College 05.Northridge Campus-ACC Austin Austin Community College 11. South Austin Campus-ACC Austin Austin Community College 06.Pinnacle Campus-ACC Austin Austin Community College 10.Highland Campus - ACC Austin Austin Community College 08.Riverside Campus-ACC Austin Lee College-INST Lee College Baytown Lamar Institute of Technology Lamar Institute of Technology-BMT Beaumont Lamar University Lamar University Career & Professional Development Beaumont Weatherford College WCWC Bridgeport UTRGV Brownsville Testing Center UT-Brownsville Brownsvillle Blinn College Blinn College - Remote TSI Assessment Bryan Panola College PC Carthage Austin Community College 02. Cypress Creek Campus-ACC Cedar Park Clarendon College CC Childress Center Childress Clarendon College Clarendon College Main Campus Clarendon Hill College Hill College-Johnson County Campus Cleburne Texas A&M University-Commerce Texas A&M-Commerce Commerce 06/05/2017 Lone Star College System Lone Star College - Montgomery Conroe Del Mar College Del Mar College Corpus -

John Ben Sutter, J.D. Curriculum Vitae (I.E., My Resume)

John Ben Sutter, J.D. Curriculum Vitae (i.e., my resume) Name: John Ben Sutter Work Address: Southeast College; 6815 Rustic; Houston, Texas, 77087 Office Telephone Number: 713.718.7112 College Email Address: [email protected] Education: • J.D., South Texas College of Law, Houston, Texas, 1995 • Postgraduate Work at The University of Texas at Austin, Government, 1991 • M.A., Baylor University, Waco, Texas, Political Science, 1983 • B.A., Baylor University, Waco, Texas, Communications and Journalism, 1975 Teaching Experience: • Professor of Government, 2000 to Present Houston Community College Courses: Government 2301 and 2302 • Full Time Government Faculty, 1994-1999 Wharton County Junior College Wharton and Sugar Land, Texas Courses: American and Texas Government • Adjunct Faculty: o Houston Community College o Wharton County Junior College o Alvin Community College o San Jacinto College o Austin Community College Professional Experience: • Special Assistant to General Jim Mattox Office of Texas Attorney General Jim Mattox Austin, Texas • Press Secretary and Administrator Office of Criminal District Attorney Vic Feazell Waco, Texas • Advertising Sales Manger SunTex Communications Waco, Texas • Public Relations Director Texas Automobile Dealers Association Austin, Texas • Press Secretary Congressional Campaign of Mike Andrews, 25th District Houston, Texas • National Advertising Sales Manager Stevens Publishing Waco, Texas • Press Secretary Congressional Campaign of Lyndon Olson, 11th District Waco, Texas • Press Secretary Office of U.S. Representative W.R. Poage, 11th District Washington, D.C. • Reporter, Morning Anchor, Weekend Weatherman KCEN-TV Temple/Waco, Texas Professional Credentials: • Texas Family Law Mediation Certification A.A. White Mediation Institute University of Houston Law School 1994 Texas Mediation Certification South Texas College of Law 1993 .