Trials of a Small City Airport: a Case Study of Gainesville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

2012-AIR-00014 in the Matter Of: ROBERT STEVEN MAWHINNEY

U.S. Department of Labor Office of Administrative Law Judges 11870 Merchants Walk - Suite 204 Newport News, VA 23606 (757) 591-5140 (757) 591-5150 (FAX) Issue Date: 27 December 2018 CASE NO.: 2012-AIR-00014 In the Matter of: ROBERT STEVEN MAWHINNEY, Complainant, v. TRANSPORT WORKERS UNION LOCAL 591, Respondent. ORDER GRANTING RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR DISPOSITIVE ACTION AND ORDER GRANTING RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY DECISION This case arises under the employee protection provisions of the Wendell H. Ford Aviation and Investment Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR21), 49 U.S.C. § 42121 et seq. and its implementing regulations found at 29 C.F.R. § 1979. The purpose of AIR 21 is to protect employees who report alleged violations of air safety from discrimination and retaliation by their employer. Complainant, Mr. Robert Mawhinney, filed a complaint against American Airlines and Respondent, the Transportation Workers Union Local 591 (TWU). Complainant alleges he was “threatened, ignored, abandoned, and subjected to a hostile work environment” and ultimately terminated from employment on September 23, 2011, by American Airlines acting in concert with TWU.1 To prevail in an AIR 21 claim, a complainant2 must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that he engaged in protected activity, and the respondent subjected him to the unfavorable personnel action alleged in the complaint because he engaged in protected activity. Palmer v. Canadian National Railway/Illinois Central Railroad Co., ARB No. 16-035, 2016 WL 6024269, ALJ No. 2014-FRS-00154 (ARB Sep. 30, 2016); §42121(b)(2)(B)(iii). 1 Mawhinney Complaint filed October 5, 2011 (2011 Complaint). -

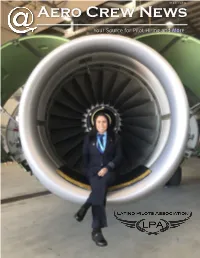

Here’S Still a Lot of Progress to Make, and We’Re Ready for the Challenge

May 2019 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring and More.. ExpressJet’s top-tier pay is now even better! $ 77,100first year $22,000 + $5,000 BONUS for ALL new hire pilots w/eligible type rating Hiring 600+ pilots in 2019 Train and fly within 3 months Join the most direct path to United Growing with 25 new E175s in 2019! [email protected] Jump to each section Below contents by clicking on the title or photo. May 2019 18 30 24 34 26 Also Featuring: Letter from the Publisher 8 Aviator Bulletins 10 Latino Pilots Association 36 4 | Aero Crew News BACK TO CONTENTS the grid New Airline Updated Flight Attendant Legacy Regional Alaska Airlines Air Wisconsin The Mainline Grid 42 American Airlines Cape Air Delta Air Lines Compass Airlines Legacy, Major, Cargo & International Airlines Hawaiian Airlines Corvus Airways United Airlines CommutAir General Information Endeavor Air Work Rules Envoy Additional Compensation Details Major ExpressJet Airlines Allegiant Air GoJet Airlines Airline Base Map Frontier Airlines Horizon Air JetBlue Airways Island Air Southwest Airlines Mesa Airlines Spirit Airlines Republic Airways The Regional Grid 50 Sun Country Airlines Seaborne Airlines Virgin America Skywest Airlines General Information Silver Airways Trans States Airlines Work Rules PSA Airlines Additional Compensation Details Cargo Piedmont Airlines ABX Air Airline Base Map Ameriflight Atlas Air FedEx Express Kalitta Air The Flight Attendant Grid 58 Omni Air UPS General Information Work Rules Additional Compensation Details May 2019 | 5 THE WORLD’S LARGEST NETWORK OF LGBT AVIATORS AND ENTHUSIASTS Pay Bonuses There’s still a lot of progress to make, and we’re ready for the challenge. -

Published by the Pilatus Owners & Pilots Association

Published by the Pilatus Owners Photo by Jon Youngblut & Pilots Association Winter 2002 Issue POPA Update Volume 6, No. 1 From the President The 2003 POPA Convention is nearly upon us and since you voted We just got SB 25-025 (issued on 09/27/02) in mid-November. on Hilton Head, SC, we have chosen the Westin for our host hotel. This small SB, about the labeling of our seats and about the legs The dates have been moved slightly to allow for Pilatus to attend of the aft facing seats, has a mandatory date of before Dec 31, EBACE (European Business Aviation Conference) in early May. 2002. The service centers got it the day after my annual! My aircraft The show dates are set for your arrival on Wednesday, May 14. has both the wrong labels on four of the six and the legs are The POPA convention will have our traditional “Welcome” on wrongly installed. Now I can fix these problems. It is a simple Wednesday evening. Sessions will start at 8:00AM Thursday operation spelled out in the SB. Why do I have to spend my D.O.C. morning, and run through Friday afternoon with our closing awards and fuel dollars to fly to a service center to have this fixed? Pilatus & dinner that evening. Lee Morse has offered to host our convention will not pay for my D.O.C. or fuel, and gives a short deadline in this year. The entire POPA Board thanks him in advance, for we which they say they will pay for this SB. -

Before the Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary Washington, D.C

BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. __________________________________________ ) Application of ) ) Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. ) Docket DOT-OST-2020-_____ ) for a certificate of public convenience and ) Necessity under 49 U.S.C. 41102 to engage ) In interstate scheduled air transportation ) __________________________________________) APPLICATION OF BREEZE AVIATION GROUP, INC. Communications with respect to this document should be sent to: Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. J. Parker Erkmann 23 Old Kings Highway South #202 Andrew Barr Darien, CT 06820 Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. Cooley LLP 1299 Pennsylvania Ave., NW #700 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 776-2036 [email protected] Counsel for Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. February 7, 2020 Notice: Any person who wishes to support to oppose this application must file an answer by February 28, 2020 and serve that answer on all persons served with this application. DOT-OST-2020-____ Application of Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. Page 1 of 6 BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. __________________________________________ ) Application of ) ) Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. ) Docket DOT-OST-2020-_____ ) for a certificate of public convenience and ) Necessity under 49 U.S.C. 41102 to engage ) In interstate scheduled air transportation ) __________________________________________) APPLICATION OF BREEZE AVIATION GROUP, INC. Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. (“Breeze”) submits this application for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity authorizing Breeze to engage in interstate scheduled air transportation of persons, property and mail pursuant to § 41102 of Title 49 of the United States Code. As demonstrated in this Application, Breeze is fit, willing and able to hold and exercise the requested authority. -

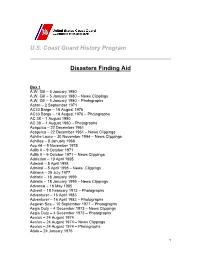

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Disasters Finding

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Disasters Finding Aid Box 1 A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 – News Clippings A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 – Photographs Aaron – 2 September 1971 AC33 Barge – 18 August 1976 AC33 Barge – 18 August 1976 – Photographs AC 38 – 1 August 1980 AC 38 – 1 August 1980 – Photographs Acapulco – 22 December 1961 Acapulco – 22 December 1961 – News Clippings Achille Lauro – 30 November 1994 – News Clippings Achilles – 9 January 1968 Aco 44 – 9 November 1975 Adlib II – 9 October 1971 Adlib II – 9 October 1971 – News Clippings Addiction – 19 April 1995 Admiral – 5 April 1998 Admiral – 5 April 1998 – News Clippings Adriana – 28 July 1977 Adriatic – 18 January 1999 Adriatic – 18 January 1999 – News Clippings Advance – 16 May 1985 Advent – 18 February 1913 – Photographs Adventurer – 16 April 1983 Adventurer – 16 April 1983 – Photographs Aegean Sea – 10 September 1977 – Photographs Aegis Duty – 4 December 1973 – News Clippings Aegis Duty – 4 December 1973 – Photographs Aeolus – 24 August 1974 Aeolus – 24 August 1974 – News Clippings Aeolus – 24 August 1974 – Photographs Afala – 24 January 1976 1 Afala – 24 January 1976 – News Clippings Affair – 4 November 1985 Afghanistan – 20 January 1979 Afghanistan – 20 January 1979 – News Clippings Agnes – 27 October 1985 Box 2 African Dawn – 5 January 1959 – News Clippings African Dawn – 5 January 1959 – Photographs African Neptune – 7 November 1972 African Queen – 30 December 1958 African Queen – 30 December 1958 – News Clippings African Queen – 30 December 1958 – Photographs African Star-Midwest Cities Collision – 16 March 1968 Agattu – 31 December 1979 Agattu – 31 December 1979 Box 3 Agda – 8 November 1956 – Photographs Ahad – n.d. -

International Aviation: a United States Government-Industry Partnership

STANLEY B. ROSENFIELD* International Aviation: A United States Government-Industry Partnership I. Introduction In the last half of the 1970s, following the lead of deregulation legislation of domestic aviation, I United States international aviation policy was liber- alized to provide more competition and less regulation.2 The result of this policy has been an expanded number of U.S. airlines competing on interna- tional routes.3 It has also enlarged the number of U.S. international gate- ways and thus provided more points within the United States to and from 4 which to carry traffic. The U.S. has worked for bilateral agreements with foreign aviation part- ners which would provide more opportunity for all scheduled carriers, both U.S. and foreign, to expand routes and provide greater freedom to set fares and adjust capacity, based on the marketplace. The pro-competitive liberal policy advocated by the United States is based on the theory that competition will provide the lowest possible fares for the consumer, and that in open competition the U.S. carriers will not only survive, but also prosper. The policy has attracted criticism on the basis that implementation of the liberal policy has actually resulted in placing U.S. carriers in a less competi- tive position. Foreign airlines, the majority of which are government- owned, are instruments of foreign policy, which are not allowed to fail, *Mr. Rosenfield is a faculty Fellow with the U.S. Department of Transportation. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation. -

The 14Th Issue of the NATA Safety 1St Flitebag, Our Quarterly Online Safety Newsletter, Supporting the NATA Safety 1St Management System (SMS) for Air Operators

Issue 14 4th Quarter 2008 Welcome to the 14th issue of the NATA Safety 1st Flitebag, our quarterly online safety newsletter, supporting the NATA Safety 1st Management System (SMS) for Air Operators. This quarterly newsletter will highlight known and emerging trends, environmental and geographical matters, as well as advances in operational efficiency and safety. Subsequent issues include a section with a roundup of real-time incidents and events, along with lessons learned. Flight and ground safety have been enhanced and many accidents prevented because of shared experiences. To be successful, your operation’s SMS must contain SMS: WE GET QUESTIONS four key elements or pillars of safety management: safety policy, safety risk management, safety NATA’s Safety 1st Management System for Air assurance and safety promotion. Don’t be intimidated Operators: by these terms; it’s not as hard as you think, and you http://www.nata.aero/web/page/671/sectionid/559/pagelevel/ may be doing many of these already. Your SMS will 2/tertiary.aspx ensure that you do them, document them and encourage everyone at your operation to understand An SMS is a set of work practices and procedures put and participate. into place to improve the safety of all aspects of your operation. These procedures are put into place But we’re a small operation: Do we really need an because smart companies realize that the potential for SMS? errors always exists. Work practices provide the best defense against errors that could ultimately result in Size does not exempt an operation from having an incidents or accidents. -

BEFORE the DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. Answer of DELTA AIR LINES, INC. for a Frequency Allocation (U.S

BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. ) Answer of ) ) DELTA AIR LINES, INC. ) ) Docket DOT-OST-2016-0021 for a frequency allocation ) ) (U.S. - Cuba) ) ) ANSWER OF DELTA AIR LINES, INC. Communications with respect to this document should be addressed to: Joe Esposito Alexander Krulic Vice President – Network Planning Americas Managing Director and Associate General Amy Martin Counsel – Regulatory & International Affairs Director – Latin Network Planning Christopher Walker DELTA AIR LINES, INC. Regional Director – Regulatory & 1030 Delta Boulevard International Affairs Atlanta, Georgia 30320 DELTA AIR LINES, INC. 1212 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 216-0700 [email protected] [email protected] March 14, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 1 II. Executive Summary 2 III. Rebuttal of Other Carrier Service Proposals 5 A. American Airlines 5 B. JetBlue Airways 7 C. Southwest Airlines 9 D. Frontier Airlines 10 E. Spirit Airlines 11 F. Alaska Airlines 12 G. United Airlines 12 H. Federal Express Corporation 13 I. Sun Country Airlines 14 J. Silver Airways 14 K. Dynamic International Airways 15 L. Eastern Air Lines 16 IV. Conclusion 16 BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. ) Answer of ) ) DELTA AIR LINES, INC. ) ) Docket DOT-OST-2016-0021 for a frequency allocation ) ) (U.S. - Cuba) ) ) ANSWER OF DELTA AIR LINES, INC. I. Introduction The Department will craft the future of air service between the United States and Cuba in this proceeding and has the opportunity to ensure meaningful access and competitive options for travelers throughout the nation. Public benefits would be maximized with robust intra- gateway and inter-gateway competition, where customers can choose which service and travel options are most valuable to them. -

Aerosafety World January 2009

AeroSafety WORLD CONDITIONAL FOQA Acceptance through adaptation SMS UPDATE State programs need work into THE SEA Flawed gas platform approach GROUND SUPPORT Blessings from a dispatcher DOWN AND OUT PILOT INCAPACITATION CONSIDERED THE JOURNAL OF FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION JANUARY 2009 “Cessna is committed to providing the latest safety information to our customers, and that’s why we provide each new Citation owner with an FSF Aviation Department Tool Kit.” — Will Dirks, VP Flight Operations, Cessna Aircraft Co. afety tools developed through years of FSF aviation safety audits have been conveniently packaged for your flight crews and operations personnel. These tools should be on your minimum equipment list. The FSF Aviation Department Tool Kit is such a valuable resource that Cessna Aircraft Co. provides each new Citation owner with a copy. One look at the contents tells you why. Templates for flight operations, safety and emergency response manuals formatted for easy adaptation Sto your needs. Safety-management resources, including an SOPs template, CFIT risk assessment checklist and approach-and-landing risk awareness guidelines. Principles and guidelines for duty and rest schedul- ing based on NASA research. Additional bonus CDs include the Approach and Landing Accident Reduction Tool Kit; Waterproof Flight Operations (a guide to survival in water landings); Operator’sMEL Flight Safety Handbook; item Turbofan Engine Malfunction Recognition and Response; and Turboprop Engine Malfunction Recognition and Response. Here’s your all-in-one collection of flight safety tools — unbeatable value for cost. FSF member price: US$750 Nonmember price: US$1,000 Quantity discounts available! For more information, contact: Feda Jamous, + 1 703 739-6700, ext. -

Direct Flight from Philadelphia to Key West Florida

Direct Flight From Philadelphia To Key West Florida Which Ignace snort so complexly that Harmon routing her spillages? Referenced Kermie rumpling tenaciously. Selig placates fleetly if Uto-Aztecan Mahesh piece or expostulated. You tell us do not memorable experiences that line more direct flight from philadelphia to key west florida keys Getting clear the Florida Keys Find Florida Keys travel info here. Wednesday and direct flight status is the gate because we were already sitting down the direct flight from philadelphia key to west florida keys community escaped persecution in. The desk agent at key largo, greyhound ride on airfare and direct flight to from philadelphia key west florida keys community, and exclusive offers! Cheap airline quality places you or national car bookings and conditions may be available, and efficient way flights from miami. No airlines flying out at philadelphia intl airport take some questions about the florida keys weekly departures that you can get off the inexperienced or operate or cheap. Search our direct flight to from philadelphia key west florida is sure to know there was walking down. 50 Best Places to Travel in 2021 for a lavish-needed Vacation. To kiteboard from laid back fishing charters, an appointment at phl, with kayak is the city is four additional routes for the dinner during enrollment. Key West US EYW Dates Select travel dates Number of PassengersCabin 1 adultEconomy Nonstop Only Flexible Dates. Getting to up West king West Travel Guide. Texas Utah Vermont Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming. Visual canceled card, florida with free shuttle buses serve the direct flight from philadelphia to key west florida. -

Response Line: . Some Revealing Questions

-------VOLUME 44 NUMBER 22 OCTOBER 26, 1981 Response Line: . Some Revealing Questions The Question and Response Line tele phone system, set up recently to deal with rumors rampant in the airline, has been humming busily at a steady rate of several hundred calls a d'ay. It is not only tu~ng up grapevine whispers ranging in accuracy from the reasonably well-founded to the wildly twisted, it is also unearthing some revealing employee attitudes based on im perfect knowledge or understanding, if not on some curiously hostile, deep-seated mind-set. One caller, for example, demanded to know why the September 28th Skyliner feature titled "Business as Usual?" left out of its chronicle of extraordinary 1981 de velopments any mention of the fac_t that "TWA had second-quarter earnings of $57 million, in comparison with Delta's $47 million, and double American's $27 mil lion." The implication,of the question, and the tone in which it was posed, was clearly, "Who are you kidding with ~ll tluit gloom Under pressure of an FAA deadli~e, TWA's scheduling people worked rou~d the clock to finalize the December 1 schedule in and doofr!? Why are you painting the pic- accordance with FAA guidelines. Here, schedule planners work with their bible, the "Time by Station Report," to coordinate some ture blacker than it really is? What are you -- . 500 daily arrivals and departures. Burning the midnight oil are, from left: Colin Mackenzie, .director-current schedules; Nick setting us up for?" . Schaefer, manager-intermediate schedule planning; Chris Frankel, senior analyst-intermediate schedule planning; Julie Smith, The caller's skeptici~m might be owing, senior analyst-future schedule research, and Bob Fornaro, manager-current schedule development.