Aerosafety World January 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAY 2010 £2.50 VOLUME 36 ISSUE 5 Z7015 Hawker Sea Hurricane 1B 880 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm(G-BKTH) Old Warden 26/09/09 Jim Stan

YORKSHIRE’S PREMIER AVIATION SOCIETY C-GBCI Falcon 20-F5 operated by Novajet Pictured at Toronto on 17/03/10 by Ian Morton N836D Douglas DC-7C of Eastern Airlines Pictured by Andrew Barker at Opa Locka, 15/03/10 Z7015 Hawker Sea Hurricane 1b 880 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm(G-BKTH) Old Warden 26/09/09 Jim Stanfield www.airyorkshire.org.uk £2.50 G-FBED Emraer 190 of Flybe departing runway 14 @ LBIA enroute to Southampton. Pictured on 18/03/10 by Robert Burke VOLUME 36 ISSUE 5 MAY 2010 SOCIETY CONTACTS HONORARY LIFE PRESIDENT Mike WILLINGALE GAMSTON RESIDENTS.......... AIR YORKSHIRE COMMITTEE 2010 One of our Doncaster correspondants, Paul Lindley managed to get a tour around the hangars at CHAIRMAN David SENIOR 23 Queens Drive, Carlton, WF3 3RQ Gamston recently and featured below is a selection of the varied inhabitants of this busy little tel: 0113 2821818 airfield near Retford. e-mail:[email protected] SECRETARY Jim STANFIELD tel: 0113 258 9968 e-mail:[email protected] N27HK is a King TREASURER David VALENTINE 8 St Margaret’s Avenue Air 200 formerly Horsforth, Leeds LS18 5RY based in Qatar tel: 0113 228 8143 as A7-AHK. Assistant Treasurer Pauline VALENTINE The aircraft MEETINGS CO-ORDINATOR Alan SINFIELD tel: 01274 619679 moved North in e-mail: [email protected] 2009 and is MAGAZINE EDITOR Trevor SMITH 97 Holt Farm Rise, Leeds LS16 7SB registered under tel: 0113 267 8441 the Southern e-mail: [email protected] Aircraft Consult- VISITS ORGANISER Paul WINDSOR tel: 0113 250 4424 ancy banner. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

COM(79)311 Final Brussels / 6Th July 1979

ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES DE LA COMMISSION COLLECTION RELIEE DES DOCUMENTS "COM" COM (79) 311 Vol. 1979/0118 Disclaimer Conformément au règlement (CEE, Euratom) n° 354/83 du Conseil du 1er février 1983 concernant l'ouverture au public des archives historiques de la Communauté économique européenne et de la Communauté européenne de l'énergie atomique (JO L 43 du 15.2.1983, p. 1), tel que modifié par le règlement (CE, Euratom) n° 1700/2003 du 22 septembre 2003 (JO L 243 du 27.9.2003, p. 1), ce dossier est ouvert au public. Le cas échéant, les documents classifiés présents dans ce dossier ont été déclassifiés conformément à l'article 5 dudit règlement. In accordance with Council Regulation (EEC, Euratom) No 354/83 of 1 February 1983 concerning the opening to the public of the historical archives of the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community (OJ L 43, 15.2.1983, p. 1), as amended by Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1700/2003 of 22 September 2003 (OJ L 243, 27.9.2003, p. 1), this file is open to the public. Where necessary, classified documents in this file have been declassified in conformity with Article 5 of the aforementioned regulation. In Übereinstimmung mit der Verordnung (EWG, Euratom) Nr. 354/83 des Rates vom 1. Februar 1983 über die Freigabe der historischen Archive der Europäischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft und der Europäischen Atomgemeinschaft (ABI. L 43 vom 15.2.1983, S. 1), geändert durch die Verordnung (EG, Euratom) Nr. 1700/2003 vom 22. September 2003 (ABI. L 243 vom 27.9.2003, S. -

Boeing 737-236 Series 1, G-BGJL: Main Document

Uncontained engine failure, Boeing 737-236 series 1, G-BGJL Micro-summary: Following an uncontained engine failure, a catastrophic fire emerged during evacuation. Event Date: 1985-08-22 at 0613 UTC Investigative Body: Aircraft Accident Investigation Board (AAIB), United Kingdom Investigative Body's Web Site: http://www.aaib.dft.gov/uk/ Note: Reprinted by kind permission of the AAIB. Cautions: 1. Accident reports can be and sometimes are revised. Be sure to consult the investigative agency for the latest version before basing anything significant on content (e.g., thesis, research, etc). 2. Readers are advised that each report is a glimpse of events at specific points in time. While broad themes permeate the causal events leading up to crashes, and we can learn from those, the specific regulatory and technological environments can and do change. Your company's flight operations manual is the final authority as to the safe operation of your aircraft! 3. Reports may or may not represent reality. Many many non-scientific factors go into an investigation, including the magnitude of the event, the experience of the investigator, the political climate, relationship with the regulatory authority, technological and recovery capabilities, etc. It is recommended that the reader review all reports analytically. Even a "bad" report can be a very useful launching point for learning. 4. Contact us before reproducing or redistributing a report from this anthology. Individual countries have very differing views on copyright! We can advise you on the steps to follow. Aircraft Accident Reports on DVD, Copyright © 2006 by Flight Simulation Systems, LLC All rights reserved. -

2012-AIR-00014 in the Matter Of: ROBERT STEVEN MAWHINNEY

U.S. Department of Labor Office of Administrative Law Judges 11870 Merchants Walk - Suite 204 Newport News, VA 23606 (757) 591-5140 (757) 591-5150 (FAX) Issue Date: 27 December 2018 CASE NO.: 2012-AIR-00014 In the Matter of: ROBERT STEVEN MAWHINNEY, Complainant, v. TRANSPORT WORKERS UNION LOCAL 591, Respondent. ORDER GRANTING RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR DISPOSITIVE ACTION AND ORDER GRANTING RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY DECISION This case arises under the employee protection provisions of the Wendell H. Ford Aviation and Investment Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR21), 49 U.S.C. § 42121 et seq. and its implementing regulations found at 29 C.F.R. § 1979. The purpose of AIR 21 is to protect employees who report alleged violations of air safety from discrimination and retaliation by their employer. Complainant, Mr. Robert Mawhinney, filed a complaint against American Airlines and Respondent, the Transportation Workers Union Local 591 (TWU). Complainant alleges he was “threatened, ignored, abandoned, and subjected to a hostile work environment” and ultimately terminated from employment on September 23, 2011, by American Airlines acting in concert with TWU.1 To prevail in an AIR 21 claim, a complainant2 must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that he engaged in protected activity, and the respondent subjected him to the unfavorable personnel action alleged in the complaint because he engaged in protected activity. Palmer v. Canadian National Railway/Illinois Central Railroad Co., ARB No. 16-035, 2016 WL 6024269, ALJ No. 2014-FRS-00154 (ARB Sep. 30, 2016); §42121(b)(2)(B)(iii). 1 Mawhinney Complaint filed October 5, 2011 (2011 Complaint). -

Neil Cloughley, Managing Director, Faradair Aerospace

Introduction to Faradair® Linking cities via Hybrid flight ® faradair Neil Cloughley Founder & Managing Director Faradair Aerospace Limited • In the next 15 years it is forecast that 60% of the Worlds population will ® live in cities • Land based transportation networks are already at capacity with rising prices • The next transportation revolution faradair will operate in the skies – it has to! However THREE problems MUST be solved to enable this market; • Noise • Cost of Operations • Emissions But don’t we have aircraft already? A2B Airways, AB Airlines, Aberdeen Airways, Aberdeen Airways, Aberdeen London Express, ACE Freighters, ACE Scotland, Air 2000, Air Anglia, Air Atlanta Europe, Air Belfast, Air Bridge Carriers, Air Bristol, Air Caledonian, Air Cavrel, Air Charter, Air Commerce, Air Commuter, Air Contractors, Air Condor, Air Contractors, Air Cordial, Air Couriers, Air Ecosse, Air Enterprises, Air Europe, Air Europe Express, Air Faisal, Air Ferry, Air Foyle HeavyLift, Air Freight, Air Gregory, Air International (airlines) Air Kent, Air Kilroe, Air Kruise, Air Links, Air Luton, Air Manchester, Air Safaris, Air Sarnia, Air Scandic, Air Scotland, Air Southwest, Air Sylhet, Air Transport Charter, AirUK, Air UK Leisure, Air Ulster, Air Wales, Aircraft Transport and Travel, Airflight, Airspan Travel, Airtours, Airfreight Express, Airways International, Airwork Limited, Airworld Alderney, Air Ferries, Alidair, All Cargo, All Leisure, Allied Airways, Alpha One Airways, Ambassador Airways, Amber Airways, Amberair, Anglo Cargo, Aquila Airways, -

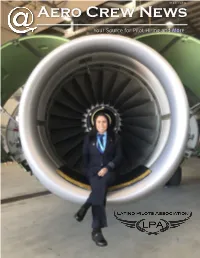

Here’S Still a Lot of Progress to Make, and We’Re Ready for the Challenge

May 2019 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring and More.. ExpressJet’s top-tier pay is now even better! $ 77,100first year $22,000 + $5,000 BONUS for ALL new hire pilots w/eligible type rating Hiring 600+ pilots in 2019 Train and fly within 3 months Join the most direct path to United Growing with 25 new E175s in 2019! [email protected] Jump to each section Below contents by clicking on the title or photo. May 2019 18 30 24 34 26 Also Featuring: Letter from the Publisher 8 Aviator Bulletins 10 Latino Pilots Association 36 4 | Aero Crew News BACK TO CONTENTS the grid New Airline Updated Flight Attendant Legacy Regional Alaska Airlines Air Wisconsin The Mainline Grid 42 American Airlines Cape Air Delta Air Lines Compass Airlines Legacy, Major, Cargo & International Airlines Hawaiian Airlines Corvus Airways United Airlines CommutAir General Information Endeavor Air Work Rules Envoy Additional Compensation Details Major ExpressJet Airlines Allegiant Air GoJet Airlines Airline Base Map Frontier Airlines Horizon Air JetBlue Airways Island Air Southwest Airlines Mesa Airlines Spirit Airlines Republic Airways The Regional Grid 50 Sun Country Airlines Seaborne Airlines Virgin America Skywest Airlines General Information Silver Airways Trans States Airlines Work Rules PSA Airlines Additional Compensation Details Cargo Piedmont Airlines ABX Air Airline Base Map Ameriflight Atlas Air FedEx Express Kalitta Air The Flight Attendant Grid 58 Omni Air UPS General Information Work Rules Additional Compensation Details May 2019 | 5 THE WORLD’S LARGEST NETWORK OF LGBT AVIATORS AND ENTHUSIASTS Pay Bonuses There’s still a lot of progress to make, and we’re ready for the challenge. -

Published by the Pilatus Owners & Pilots Association

Published by the Pilatus Owners Photo by Jon Youngblut & Pilots Association Winter 2002 Issue POPA Update Volume 6, No. 1 From the President The 2003 POPA Convention is nearly upon us and since you voted We just got SB 25-025 (issued on 09/27/02) in mid-November. on Hilton Head, SC, we have chosen the Westin for our host hotel. This small SB, about the labeling of our seats and about the legs The dates have been moved slightly to allow for Pilatus to attend of the aft facing seats, has a mandatory date of before Dec 31, EBACE (European Business Aviation Conference) in early May. 2002. The service centers got it the day after my annual! My aircraft The show dates are set for your arrival on Wednesday, May 14. has both the wrong labels on four of the six and the legs are The POPA convention will have our traditional “Welcome” on wrongly installed. Now I can fix these problems. It is a simple Wednesday evening. Sessions will start at 8:00AM Thursday operation spelled out in the SB. Why do I have to spend my D.O.C. morning, and run through Friday afternoon with our closing awards and fuel dollars to fly to a service center to have this fixed? Pilatus & dinner that evening. Lee Morse has offered to host our convention will not pay for my D.O.C. or fuel, and gives a short deadline in this year. The entire POPA Board thanks him in advance, for we which they say they will pay for this SB. -

Before the Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary Washington, D.C

BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. __________________________________________ ) Application of ) ) Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. ) Docket DOT-OST-2020-_____ ) for a certificate of public convenience and ) Necessity under 49 U.S.C. 41102 to engage ) In interstate scheduled air transportation ) __________________________________________) APPLICATION OF BREEZE AVIATION GROUP, INC. Communications with respect to this document should be sent to: Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. J. Parker Erkmann 23 Old Kings Highway South #202 Andrew Barr Darien, CT 06820 Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. Cooley LLP 1299 Pennsylvania Ave., NW #700 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 776-2036 [email protected] Counsel for Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. February 7, 2020 Notice: Any person who wishes to support to oppose this application must file an answer by February 28, 2020 and serve that answer on all persons served with this application. DOT-OST-2020-____ Application of Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. Page 1 of 6 BEFORE THE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. __________________________________________ ) Application of ) ) Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. ) Docket DOT-OST-2020-_____ ) for a certificate of public convenience and ) Necessity under 49 U.S.C. 41102 to engage ) In interstate scheduled air transportation ) __________________________________________) APPLICATION OF BREEZE AVIATION GROUP, INC. Breeze Aviation Group, Inc. (“Breeze”) submits this application for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity authorizing Breeze to engage in interstate scheduled air transportation of persons, property and mail pursuant to § 41102 of Title 49 of the United States Code. As demonstrated in this Application, Breeze is fit, willing and able to hold and exercise the requested authority. -

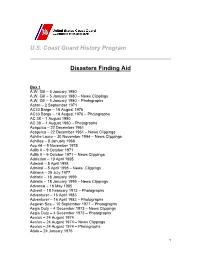

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Disasters Finding

U.S. Coast Guard History Program Disasters Finding Aid Box 1 A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 – News Clippings A.W. Gill – 5 January 1980 – Photographs Aaron – 2 September 1971 AC33 Barge – 18 August 1976 AC33 Barge – 18 August 1976 – Photographs AC 38 – 1 August 1980 AC 38 – 1 August 1980 – Photographs Acapulco – 22 December 1961 Acapulco – 22 December 1961 – News Clippings Achille Lauro – 30 November 1994 – News Clippings Achilles – 9 January 1968 Aco 44 – 9 November 1975 Adlib II – 9 October 1971 Adlib II – 9 October 1971 – News Clippings Addiction – 19 April 1995 Admiral – 5 April 1998 Admiral – 5 April 1998 – News Clippings Adriana – 28 July 1977 Adriatic – 18 January 1999 Adriatic – 18 January 1999 – News Clippings Advance – 16 May 1985 Advent – 18 February 1913 – Photographs Adventurer – 16 April 1983 Adventurer – 16 April 1983 – Photographs Aegean Sea – 10 September 1977 – Photographs Aegis Duty – 4 December 1973 – News Clippings Aegis Duty – 4 December 1973 – Photographs Aeolus – 24 August 1974 Aeolus – 24 August 1974 – News Clippings Aeolus – 24 August 1974 – Photographs Afala – 24 January 1976 1 Afala – 24 January 1976 – News Clippings Affair – 4 November 1985 Afghanistan – 20 January 1979 Afghanistan – 20 January 1979 – News Clippings Agnes – 27 October 1985 Box 2 African Dawn – 5 January 1959 – News Clippings African Dawn – 5 January 1959 – Photographs African Neptune – 7 November 1972 African Queen – 30 December 1958 African Queen – 30 December 1958 – News Clippings African Queen – 30 December 1958 – Photographs African Star-Midwest Cities Collision – 16 March 1968 Agattu – 31 December 1979 Agattu – 31 December 1979 Box 3 Agda – 8 November 1956 – Photographs Ahad – n.d. -

International Aviation: a United States Government-Industry Partnership

STANLEY B. ROSENFIELD* International Aviation: A United States Government-Industry Partnership I. Introduction In the last half of the 1970s, following the lead of deregulation legislation of domestic aviation, I United States international aviation policy was liber- alized to provide more competition and less regulation.2 The result of this policy has been an expanded number of U.S. airlines competing on interna- tional routes.3 It has also enlarged the number of U.S. international gate- ways and thus provided more points within the United States to and from 4 which to carry traffic. The U.S. has worked for bilateral agreements with foreign aviation part- ners which would provide more opportunity for all scheduled carriers, both U.S. and foreign, to expand routes and provide greater freedom to set fares and adjust capacity, based on the marketplace. The pro-competitive liberal policy advocated by the United States is based on the theory that competition will provide the lowest possible fares for the consumer, and that in open competition the U.S. carriers will not only survive, but also prosper. The policy has attracted criticism on the basis that implementation of the liberal policy has actually resulted in placing U.S. carriers in a less competi- tive position. Foreign airlines, the majority of which are government- owned, are instruments of foreign policy, which are not allowed to fail, *Mr. Rosenfield is a faculty Fellow with the U.S. Department of Transportation. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation. -

The 14Th Issue of the NATA Safety 1St Flitebag, Our Quarterly Online Safety Newsletter, Supporting the NATA Safety 1St Management System (SMS) for Air Operators

Issue 14 4th Quarter 2008 Welcome to the 14th issue of the NATA Safety 1st Flitebag, our quarterly online safety newsletter, supporting the NATA Safety 1st Management System (SMS) for Air Operators. This quarterly newsletter will highlight known and emerging trends, environmental and geographical matters, as well as advances in operational efficiency and safety. Subsequent issues include a section with a roundup of real-time incidents and events, along with lessons learned. Flight and ground safety have been enhanced and many accidents prevented because of shared experiences. To be successful, your operation’s SMS must contain SMS: WE GET QUESTIONS four key elements or pillars of safety management: safety policy, safety risk management, safety NATA’s Safety 1st Management System for Air assurance and safety promotion. Don’t be intimidated Operators: by these terms; it’s not as hard as you think, and you http://www.nata.aero/web/page/671/sectionid/559/pagelevel/ may be doing many of these already. Your SMS will 2/tertiary.aspx ensure that you do them, document them and encourage everyone at your operation to understand An SMS is a set of work practices and procedures put and participate. into place to improve the safety of all aspects of your operation. These procedures are put into place But we’re a small operation: Do we really need an because smart companies realize that the potential for SMS? errors always exists. Work practices provide the best defense against errors that could ultimately result in Size does not exempt an operation from having an incidents or accidents.