Re-Regulation and Airline Passengers' Rights Timothy M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

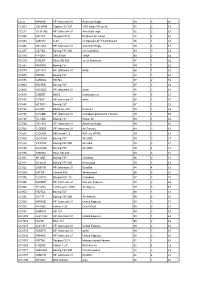

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Report to the Legislature: Indoor Air Pollution in California

California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board Report to the California Legislature INDOOR AIR POLLUTION IN CALIFORNIA A report submitted by: California Air Resources Board July, 2005 Pursuant to Health and Safety Code § 39930 (Assembly Bill 1173, Keeley, 2002) Arnold Schwarzenegger Governor Indoor Air Pollution in California July, 2005 ii Indoor Air Pollution in California July, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared with the able and dedicated support from Jacqueline Cummins, Marisa Bolander, Jeania Delaney, Elizabeth Byers, and Heather Choi. We appreciate the valuable input received from the following groups: • Many government agency representatives who provided information and thoughtful comments on draft reports, especially Jed Waldman, Sandy McNeel, Janet Macher, Feng Tsai, and Elizabeth Katz, Department of Health Services; Richard Lam and Bob Blaisdell, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment; Deborah Gold and Bob Nakamura, Cal/OSHA; Bill Pennington and Bruce Maeda, California Energy Commission; Dana Papke and Kathy Frevert, California Integrated Waste Management Board; Randy Segawa, and Madeline Brattesani, Department of Pesticide Regulation; and many others. • Bill Fisk, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, for assistance in assessing the costs of indoor pollution. • Susan Lum, ARB, project website management, and Chris Jakober, for general technical assistance. • Stakeholders from the public and private sectors, who attended the public workshops and shared their experiences and suggestions -

The 22Nd Annual Greater Washington Aviation Open

THE 22ND ANNUAL GREatER WASHINgtON AVIatION OPEN Charity Golf Tournament & Auction Lansdowne Resort Lansdowne, Virginia May 24, 2010 3213 Duke Street, #207, AlexAndriA, VirginiA 22314 • www.gwAo.org Dear Friends of the GWAO: We welcome everyone to the 22nd Annual Greater Washington Aviation Open – the largest aviation charity event in Washington, DC. Given the state of the economy, it is a testament to the great support the tournament has received from the aviation industry. As our contributions from the GWAO to the Corporate Angel Network continue to grow, so has the number of cancer patients they have transported to treatment facilities across the country. CAN has now transported over 34,000 patients in the empty seats of corporate aircraft for life-saving medical treatment at some of our nation’s finest hospitals. We are very pleased to have Clay Jones, Chairman, President, and CEO of Rockwell Collins, serve as our Honorary Chairman this year. Clay has served on many important aviation boards, and his leadership and service are recognized by all in the industry. His participation today as our Honorary Chairman of the 22nd Annual GWAO is appreciated and well warranted. The GWAO would not be the premier charity event that it is without the tremendous support of Diamond Sponsor FlightSafety International and Gold Sponsor Aviation Partners Boeing. Through their very generous donations we are well on our way to a successful tournament. They are joined by other major donors in this program and are on our signage in recognition of their wonderful support. The airlines that have donated tickets for the live auction this year also merit our special recognition. -

TWA's Caribbean Flights Caribbean Cure for The

VOLUME 48 NUMBER 9 MAY 6, 1985 Caribbean . TWA's Caribbean Flights Cure for The Doldrums TWA will fly to the Caribbean this fall, President Ed Meyer announced. The air line willserve nine Caribbean destinations from New York starting November 15; at the same time, it will inaugurate non-stop service between St. Louis and SanJuan. Islands to be served are St. Thomas, the Bahamas, St. Maarten, St. Croix, Antigua, Martinique, Guadeloupe and Puerto Rico. For more than a decade TWA has con sistently been the leading airline across . the North Atlantic in terms of passengers carried. With the addition of the Caribbean routes, TWA willadd an important North South dimension to its internationalserv ices, Mr. Meyer said. "We expect that strong winter loads to Caribbean vacation destinations will help TWA counterbalance relatively light transatlantic traffic at that time of year, . and vice versa," he explained. "Travelers willbenefit from TWA's premiere experi ence in international operations and its reputation for excellent service," he added. Mr. Meyer emphasized TWA's leader ship as the largest tour operator across the Atlantic, and pointed to the airline's feeder network at both Kennedy and St. Louis: "Passengers from the west and midwest caneasily connect into these ma- (topage4) Freeport � 1st Quarter: Nassau SAN JUAN A Bit Better St. Thomas With the publication of TWA's first-quar St. Croix ter financial results,· the perennial ques tion recurs: "With load factors like that, how could we lose so much money?" Martinique As always, the answer isn't simple. First the numbers, then the words. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Jetblue Honors Public Servants for Inspiring Humanity

www.MetroAirportNews.com Serving the Airport Workforce and Local Communities June 2017 research to create international awareness for INSIDE THIS ISSUE neuroblastoma. Last year’s event raised $123,000. All in attendance received a special treat, a first glimpse at JetBlue’s newest special livery — “Blue Finest” — dedicated to New York City’s more than 36,000 officers. Twenty three teams, consisting of nearly 300 participants, partici- pated in timed trials to pull “Blue Finest,” an Airbus 320 aircraft, 100 feet in the fastest amount of time to raise funds for the J-A-C-K Foundation. Participants were among the first to view this aircraft adorned with the NYPD flag, badge and shield. “Blue Finest” will join JetBlue’s fleet flying FOD Clean Up Event at JFK throughout the airline’s network, currently 101 Page 2 JetBlue Honors Public Servants cities and growing. The aircraft honoring the NYPD joins JetBlue’s exclusive legion of ser- for Inspiring Humanity vice-focused aircraft including “Blue Bravest” JetBlue Debuts ‘Blue Finest’ Aircraft dedicated to the FDNY, “Vets in Blue” honoring veterans past and present and “Bluemanity” - a Dedicated to the New York Police Department tribute to all JetBlue crewmembers who bring JetBlue has a long history of supporting those department competed against teams including the airline’s mission of inspiring humanity to who serve their communities. Today public ser- JetBlue crewmembers and members from local life every day. vants from New York and abroad joined forces authorities including the NYPD and FDNY to “As New York’s Hometown Airline, support- for a good cause. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

New Airlines Are Mailing National Headlines the Civil Aeronautics Board Has Approved 109 Helicopters

f=*i£^am am rotp page two Industry notes New airlines are mailing national headlines The Civil Aeronautics Board has approved 109 helicopters. The helicopter shuttle flights percent below standard fares charged by major the proposed merger of Republic Airlines and will be offered by a company called New York commercial airlines. Hughes Air West. Republic, a recent product of Air which has no connection with the New York Loftliedr bypassed air traffic treaties by the Board’s generally favorable policy toward Air that will start jetliner shuttle flights between staying out of the International Air Traffic mergers, was created by the union of North LaGuardia and Washington National on Decem Association (lATA) and by using Luxembourg Central Airlines and Southern Airways. ber 14. as its European base. The Republic merger with Air West will The latter New York Air is a subsidiary of American students made it their carrier for create the country’s 11th largest carrier in terms Texas Air Corp., the recently formed parent summers abroad, and in Europe Greeks, Italians, of revenue passenger miles. Presidential approval holding company of Texas International Airlines. Germans, Frenchmen and Dutchmen flocked to was not required because there won’t be a formal The CAB has tentatively granted a certificate to Luxembourg to use the airline, which once ran transfer of route certificates. Hughes Air West the Texas Air subsidiary which was founded to as many as 25 flights a week each way. will become a subsidiary airline, named Republic compete in the New York-Washington shuttle The airline made a stopover at Keflavik Air Airlines West. -

Overview and Trends

9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 15 1 M Overview and Trends The Transportation Research Board (TRB) study committee that pro- duced Winds of Change held its final meeting in the spring of 1991. The committee had reviewed the general experience of the U.S. airline in- dustry during the more than a dozen years since legislation ended gov- ernment economic regulation of entry, pricing, and ticket distribution in the domestic market.1 The committee examined issues ranging from passenger fares and service in small communities to aviation safety and the federal government’s performance in accommodating the escalating demands on air traffic control. At the time, it was still being debated whether airline deregulation was favorable to consumers. Once viewed as contrary to the public interest,2 the vigorous airline competition 1 The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 was preceded by market-oriented administra- tive reforms adopted by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) beginning in 1975. 2 Congress adopted the public utility form of regulation for the airline industry when it created CAB, partly out of concern that the small scale of the industry and number of willing entrants would lead to excessive competition and capacity, ultimately having neg- ative effects on service and perhaps leading to monopolies and having adverse effects on consumers in the end (Levine 1965; Meyer et al. 1959). 15 9310-01 Chapter 1 10/12/99 14:48 Page 16 16 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY spurred by deregulation now is commonly credited with generating large and lasting public benefits. -

Automated Flight Statistics Report For

DENVER INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TOTAL OPERATIONS AND TRAFFIC March 2014 March YEAR TO DATE % of % of % Grand % Grand Incr./ Incr./ Total Incr./ Incr./ Total 2014 2013 Decr. Decr. 2014 2014 2013 Decr. Decr. 2014 OPERATIONS (1) Air Carrier 36,129 35,883 246 0.7% 74.2% 99,808 101,345 (1,537) -1.5% 73.5% Air Taxi 12,187 13,754 (1,567) -11.4% 25.0% 34,884 38,400 (3,516) -9.2% 25.7% General Aviation 340 318 22 6.9% 0.7% 997 993 4 0.4% 0.7% Military 15 1 14 1400.0% 0.0% 18 23 (5) -21.7% 0.0% TOTAL 48,671 49,956 (1,285) -2.6% 100.0% 135,707 140,761 (5,054) -3.6% 100.0% PASSENGERS (2) International (3) Inbound 68,615 58,114 10,501 18.1% 176,572 144,140 32,432 22.5% Outbound 70,381 56,433 13,948 24.7% 174,705 137,789 36,916 26.8% TOTAL 138,996 114,547 24,449 21.3% 3.1% 351,277 281,929 69,348 24.6% 2.8% International/Pre-cleared Inbound 42,848 36,668 6,180 16.9% 121,892 102,711 19,181 18.7% Outbound 48,016 39,505 8,511 21.5% 132,548 108,136 24,412 22.6% TOTAL 90,864 76,173 14,691 19.3% 2.0% 254,440 210,847 43,593 20.7% 2.1% Majors (4) Inbound 1,698,200 1,685,003 13,197 0.8% 4,675,948 4,662,021 13,927 0.3% Outbound 1,743,844 1,713,061 30,783 1.8% 4,724,572 4,700,122 24,450 0.5% TOTAL 3,442,044 3,398,064 43,980 1.3% 75.7% 9,400,520 9,362,143 38,377 0.4% 75.9% National (5) Inbound 50,888 52,095 (1,207) -2.3% 139,237 127,899 11,338 8.9% Outbound 52,409 52,888 (479) -0.9% 139,959 127,940 12,019 9.4% TOTAL 103,297 104,983 (1,686) -1.6% 2.3% 279,196 255,839 23,357 9.1% 2.3% Regionals (6) Inbound 382,759 380,328 2,431 0.6% 1,046,306 1,028,865 17,441 1.7% Outbound -

2012-AIR-00014 in the Matter Of: ROBERT STEVEN MAWHINNEY

U.S. Department of Labor Office of Administrative Law Judges 11870 Merchants Walk - Suite 204 Newport News, VA 23606 (757) 591-5140 (757) 591-5150 (FAX) Issue Date: 27 December 2018 CASE NO.: 2012-AIR-00014 In the Matter of: ROBERT STEVEN MAWHINNEY, Complainant, v. TRANSPORT WORKERS UNION LOCAL 591, Respondent. ORDER GRANTING RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR DISPOSITIVE ACTION AND ORDER GRANTING RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY DECISION This case arises under the employee protection provisions of the Wendell H. Ford Aviation and Investment Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR21), 49 U.S.C. § 42121 et seq. and its implementing regulations found at 29 C.F.R. § 1979. The purpose of AIR 21 is to protect employees who report alleged violations of air safety from discrimination and retaliation by their employer. Complainant, Mr. Robert Mawhinney, filed a complaint against American Airlines and Respondent, the Transportation Workers Union Local 591 (TWU). Complainant alleges he was “threatened, ignored, abandoned, and subjected to a hostile work environment” and ultimately terminated from employment on September 23, 2011, by American Airlines acting in concert with TWU.1 To prevail in an AIR 21 claim, a complainant2 must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that he engaged in protected activity, and the respondent subjected him to the unfavorable personnel action alleged in the complaint because he engaged in protected activity. Palmer v. Canadian National Railway/Illinois Central Railroad Co., ARB No. 16-035, 2016 WL 6024269, ALJ No. 2014-FRS-00154 (ARB Sep. 30, 2016); §42121(b)(2)(B)(iii). 1 Mawhinney Complaint filed October 5, 2011 (2011 Complaint). -

Nantucket Memorial Airport Page 32

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL AIR TRANSPORTATION ASSOCIATION 2nd Quarter 2011 Nantucket Memorial Airport page 32 Also Inside: • A Workers Compensation Controversy • Swift Justice: DOT Enforcement • Benefits of Airport Minimum Standards GET IT ALL AT AVFUEL All Aviation Fuels / Contract Fuel / Pilot Incentive Programs Fuel Quality Assurance / Refueling Equipment / Aviation Insurance Fuel Storage Systems / Flight Planning and Trip Support Global Supplier of Aviation Fuel and Services 800.521.4106 • www.avfuel.com • facebook.com/avfuel • twitter.com/AVFUELtweeter NetJets Ad - FIRST, BEST, ONLY – AVIATION BUSINESS JOURNAL – Q2 2011 First. Best. Only. NetJets® pioneered the concept of fractional jet ownership in 1986 and became a Berkshire Hathaway company in 1998. And to this day, we are driven to be the best in the business without compromise. It’s why our safety standards are so exacting, our global infrastructure is so extensive, and our service is so sophisticated. When it comes to the best in private aviation, discerning fl iers know there’s Only NetJets®. SHARE | LEASE | CARD | ON ACCOUNT | MANAGEMENT 1.877.JET.0139 | NETJETS.COM A Berkshire Hathaway company All fractional aircraft offered by NetJets® in the United States are managed and operated by NetJets Aviation, Inc. Executive Jet® Management, Inc. provides management services for customers with aircraft that are not fractionally owned, and provides charter air transportation services using select aircraft from its managed fleet. Marquis Jet® Partners, Inc. sells the Marquis Jet Card®. Marquis Jet Card flights are operated by NetJets Aviation under its 14 CFR Part 135 Air Carrier Certificate. Each of these companies is a wholly owned subsidiary of NetJets Inc.