Koch V. Christie's International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September INTERNA TIONAL 2010

INSPIRATIONAL WINE KNOWLEDGE AND THE PEOPLE BEHIND THE DRINK September INTERNA TIONAL 2010 Red wine from the Canaries Changes in Argentina & Chile Genuine fakes PAGE 8 PAGE 14 PAGE 5 INNEHÅLL > PAGE 5 Genuine fakes PAGE 8 Red Wine from the Canaries?!, Who’d have believed it… PAGE 14 Winds of Change In Chile and Argentina PAGE 24 Bubbles Rise To The Top A visit from Friexenet PAGE 27 Fine Wine Tasting 2010 PAGE 35 Autumn Stews and Wild, Wild Wines PAGE 36 Ständigt aktuella Chateau la Nerthe PAGE 39 Kajsa Bergqvist - Raising The Bar on Fine Wines PAGE 40 Wine tours with BK Wine PAGE 41 The Rocky Road to Success PAGE 44 One For The Pot PAGE 46 Summary of an Administration NEWS WINE CONSUMPTION ON THE INCREASE IN USA IN SPITE OF A CRITIcaL YEAR Att USA är en av de mest vitala vinmarknader vet vi sedan länge. Allt fler produ- center runt om i världen riktar sina marknadsföringskrafter mot landet och det ger uppenbarligen resultat. Nu kommer nämligen rapporter om att vinkonsumtionen under krisåret 2009 ökade, om än marginellt. Det var konsumtionen av det inhem- ska vinet, det görs idag vin i 49 av landets 50 stater, som stod för den totala öknin- gen, med 1,8 procent. Detta innebar att vinförsäljningen landade på 3,5 miljarder flaskor vin under förra året. Samtidigt rapporterar Beverage Information Group att importen av vin minskade med 2,2 procent. Samtidigt tror analytiker att den ameri- kanska marknaden kommer att växa ännu mer och tror på en försäljning om över 3,7 miljarder flaskor vin år 2014. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Wine, Fraud and Expertise

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Wine, Fraud and Expertise THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Valerie King Thesis Committee: Professor Simon Cole, Chair Assistant Professor Bryan Sykes Professor George Tita 2015 © 2019 Valerie King TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION 1 I. FINE WINE AND COLLECTOR FRAUD 4 II. WINE, SUBJECTIVITY AND SCIENCE 20 III. WHO IS A WINE FRAUD EXPERT? 23 CONCLUSION 28 REFERENCES 30 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Simon Cole, Assistant Professor Bryan Sykes and Professor George Tita. iii ABSTRACT Wine, Fraud and Expertise By Valerie King Master of Arts in Social Ecology University of California, Irvine, 2019 Professor Simon Cole, Chair While fraud has existed in various forms throughout the history of wine, the establishment of the fine and rare wine market generated increased opportunities and incentives for producing counterfeit wine. In the contemporary fine and rare wine market, wine fraud is a serious concern. The past several decades witnessed significant events of fine wine forgery, including the infamous Jefferson bottles and the more recent large-scale counterfeit operation orchestrated by Rudy Kurniawan. These events prompted and renewed market interest in wine authentication and fraud detection. Expertise in wine is characterized by the relationship between subjective and objective judgments. The development of the wine fraud expert draws attention to the emergence of expertise as an industry response to wine fraud and the relationship between expert judgment and modern science. iv INTRODUCTION In December 1985, at Christie’s of London, a single bottle of 1787 Château Lafitte Bordeaux, was auctioned for $156,000, setting a record for the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold (Wallace 2008). -

Pinotfile Volume 6, Issue 59 the First Wine Newsletter Exclusively Devoted to Pinotphiles

Pinot Noir Refuses to Bow to any Covenant of Man PinotFile Volume 6, Issue 59 The First Wine Newsletter Exclusively Devoted to Pinotphiles May 26, 2008 Inside this issue: Inside this issue: Domaine Drouhin: Burgundy’s Blush Pinot Noir 6 Footprint in Oregon Triple Digit Pinot 10 Some young people are lucky enough to get a new car from their parents. Vero- Road 31 Wine Co. 11 nique-Boss Drouhin got her own vineyard and winery. Veronique-Boss Drouhin is Road 31 Wine Co. 11 the daughter of Robert Drouhin, who along with Veronique’s two brothers, over- 2006 DLN Pinots 12 2006 DLN Pinots 12 sees the prestigious nègociant house in Beaune, Maison Joseph Drouhin. Founded Pinot Days 2008 14 in 1957 by Robert’s great uncle, Maison Joseph Drouhin has a lofty image among Pinot Days 2008 14 Freeman Style 15 respected nègociants in Burgundy. Freeman Style/ Au- 15 Growing up in a winemaking family, Veronique was destined gustAugust West West 16 to become the fourth generation to fulfill the family’s tradition. Billionaire’s Vinegar 17 She graduated from Dijon University in 1985 and with urgings from her father, traveled to Oregon in 1986 to receive practical experience in winemaking according to the gospel of David with David Lett at Eyrie Vineyards, David Casteel of Bethel Heights, and David Adelsheim of Adelsheim Vineyard. Robert Drouhin had visited Oregon in 1961 and was struck by the re- semblance of the Williamette Valley to the Cote d’Or. He was particularly im- pressed by David Lett’s Eyrie Vineyards 1975 South Block Reserve Pinot Noir which finished ahead of some of Drouhin’s Burgundies in blind tastings. -

An Assessment of the World Wine Auction Marketplace

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2008 An Assessment of the world wine auction marketplace Michael M. Bowden University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Food and Beverage Management Commons Repository Citation Bowden, Michael M., "An Assessment of the world wine auction marketplace" (2008). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 432. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1651779 This Professional Paper is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Professional Paper in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Professional Paper has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Assessment of the World Wine Auction Marketplace By Michael M. Bowden Bachelor of Science Northern Arizona University 2004 A professional paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Hospitality Administration William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration -

A Mother's Love

SPRING 2014 MY UNCLE AL CAPONE EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH DEIRDRE CAPONE SECRET HISTORY OF BASEBALL AS TOLD BY MLB HISTORIAN JOHN THORN THE REAL FIRST THANKSGIVING IN ST. AUGUSTINE COUNTERFEIT RARE WINES STORY OF A BILLIONAIRE'S SOUR GRAPES a Mother’s love ELENA SHUMILOVA’S PHOTOGRAPHY ON HER FARM IN ANDREAPOLSKY, RUSSIA Murano At Portofino The Aragon Continuum NorthSt. TropezTower Miami Beach, Florida Boca Raton, Florida MiamiSunny Beach, Isles, FloridaFlorida THE FINEST IN LUXURY RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY MANAGEMENT CSI Management Services is a full-service property management company focused exclusively on high-end, luxury residential properties. We offer the highest levels of technical and management competence in residential property management, and our client services include, but are not limited to: • On Site Management by LCAM Managers • Janitorial, General Maintenance and Engineering • Accounting and Financial Management • Precise Management Transition Plans • Vendor Evaluation and Supervision • Building Inspection and Regular Site Visits • First Class Customer Service and Concierge CONTACT US TODAY FOR A FREE EVALUATION OF YOUR ASSOCIATION AND PROPOSAL Fort Lauderdale Headquarters • 6700 North Andrews Avenue, Suite 400 Phone: 954.308.4305 • Fax: 954.331.6028 www.csimsi.com Home is your sanctuary You juggle important responsibilities, manage critical priorities, and meet impossible deadlines. love where You don’t need a typical luxury real estate agent. You need a company that knows coming home you live means leaving the world behind. -

What's in the Bottle? an Investigation Into the Startling Fraud Accusations That Have Upended the Fine Wine World

PRINT DRINK What's in the Bottle? An investigation into the startling fraud accusations that have upended the fine wine world. By Mike Steinberger Posted Monday, June 14, 2010, at 3:36 PM ET Daniel Oliveros and Jeff Sokolin were known as the "sexy boys" because they often described the wines they sold as "sexy juice." Oliveros and Sokolin ran Royal Wine Merchants, a Manhattan retailer that was, untila few years ago, one of the biggest players in the fine wine market. They lived as lavishly as their wealthy customers—staying in swank hotels, often hiring limousines, and routinely opening thousands of dollars' worth of rare wines. Oliveros' marriage to porn star Savanna Samson added to the aura and the intrigue. But what really set the sexy boys apart was their seemingly limitless stock of legendary old wines, many of them in supersize bottles—quantities and formats that no one else could get their hands on. They bombarded clients with faxes touting their latest finds: multiple bottles of 1961 Latour à Pomerol ("Kinky Juice!"), magnums of 1945 Mouton Rothschild ("our latest sexy purchase"), a double magnum of 1949 Cheval Blanc ("Perfect condition. Better than 1947!!! Trust me!!!"). It seemed too good to be true. Apparently, it was. Billionaire wine collector BillKoch recently filed a lawsuit against Christie's auction house that includes some provocative claims about Oliveros and Sokolin. Third-party import records obtained by Koch suggest that Royal served as a conduit for Hardy Rodenstock, the suspected wine counterfeiter at the heart of the flap over the so-called Thomas Jefferson bottles. -

NABCA Daily News Update (1/28/2019) 2

Control State News January 28, 2019 UT: In the new Utah legislature: the future of 3.2 beer SAVE THE DATE OH: Ohio liquor agents crack down on alcohol sales that March 17-19, 2019 lead to accidents 26th Annual Symposium on ID: Advocates of Idaho liquor license reform are hopeful a Alcohol Beverage Law and Regulation Registration is open for NABCA’s 2019 Legal Symposium. new legislative bill will hit the spot For program details, travel information and to register online, please click here. License State News WA: Washington regulators ponder new vaping rules that NABCA HIGHLIGHTS mimic alcohol, marijuana regulations The Public Health Considerations of Fetal International News Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (White Paper) South Asia: Are we becoming a nation of boozers? Native American Nations & State Alcohol Policies: An Analysis (White Paper) Public Health News Alcohol Technology in the World of Tomorrow - (White Paper) Marijuana for pain: hype or hope? The Control State Agency Info Sheets. Please Industry News view website for more information. NABCA Survey Database (members only) The Russian market: evolving towards a healthier future Upcoming NABCA Meetings No One Is Safe From Counterfeit Wine Statistical Data Reports Education News www.NABCA.org Dartmouth sees rise in alcohol incidents Daily News CBJ: What’s in a label? A lot when it comes to alcohol Prohibition Exhibit Highlights the 18th Amendment’s Historical Impact on the Brew City It took 162 years, but this Massachusetts town now has a grocery store that can sell alcohol Woman got drunk off vanilla extract NABCA Daily News Update (1/28/2019) 2 CONTROL STATE NEWS UT: In the new Utah legislature: the future of 3.2 beer Cache Valley Daily Written by Craig Hislop January 28, 2019 Utahns consume 33 million gallons of beer a year. -

Syracuse Journal of Science & Technology

SYRACUSE JOURNAL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY LAW VOLUME 34 2017-2018 TABLE OF CONTENts Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battle to Collect Your Data and Control Your World Reviewed by Annie Millar Hate Crimes in Cyberspace Reviewed by Teal Johnson The Innovation Act (H.R. 9): The impact it will have on non-frivolous lawsuits Thomas L. Carlon Sorting the Beef from the Bull: The Science of Food Fraud Forensics Reviewed by Samantha Cirillo Application of the Halo Standard in U.S. District Courts Nicholas Dellefave Conflicting Ideas: Broadband, FCC, and New York Nicholas Fedorka Intellectual Property and Public Health in the Developing World Reviewed by Annie Millar USPTO Guidelines: Effects on Natural Product Pharmaceuticals Lindsey M. Round Juvenile Justice Reform in New York: Prosecuting the Adolescent Brain Cecilia M. Santostefano 19858_JOST_Publication_4.indd 1 8/27/18 11:25 AM SYRACUSE JOURNAL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY LAW VOLUME 34 2017-2018 2016 - 2017 Editorial Staff EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Emma Fusco MANAGING EDITOR Thomas Carlon NOTES & COMMENTS EDITORS FORM & AccURACY EDITORS Nicholas Fedorka Lindsey Round Cecilia Santostefano Aidan Scott LEAD ARTICLE EDITOR TECHNOLOGY EDITOR Gurshamsheer Kailey Annie Millar EXECUTIVE EDITORS Brittany Charles Teal Johnson Samantha Cirillo Lishayne King Nicholas Dellefave Xianq Qi Julian Harrison EXECUTIVE EDITORS Cody Andrushko Ahmed Khattab Laura O’Brien Connor Barnett Christopher McIlveen Rachel Theodorou Jacqueline Collins Parker Mincy Kristian Walker Emma Coppola Elle Nainstein Amanda Wang Melissa Goldstein Xiaotong Wang 2 19858_JOST_Publication_4.indd 2 8/27/18 11:25 AM Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battle to Collect Your Data and Control Your World Reviewed by Annie Millar1 Citation: Bruce Schneier, DATA AND GOLIATH: THE HIDDEN BATTLE TO COLLECT YOUR DATA AND CONTROL (2015). -

The Billionaire's Vinegar: the Mystery of the World's Most Expensive Bottle of Wine by Benjamin Wallace, Broadway Books, 2009

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University LAS Faculty Book Reviews College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 3-1-2011 The Billionaire's Vinegar: The Mystery of the World's Most Expensive Bottle of Wine by Benjamin Wallace, Broadway Books, 2009 Paul Hanson Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/las_bookreviews Recommended Citation Hanson, Paul, "The Billionaire's Vinegar: The Mystery of the World's Most Expensive Bottle of Wine by Benjamin Wallace, Broadway Books, 2009" (2011). LAS Faculty Book Reviews. 76. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/las_bookreviews/76 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in LAS Faculty Book Reviews by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Because Ideas Matter... The faculty and staff of Butler University's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences presents Recommended Readings The Billionaire's Vinegar: The Mystery of the World's Most Expensive Bottle of Wine by Benjamin Wallace Reviewed by Paul Hanson In 1985 a bottle of 1787 Château Lafite Bordeaux was put up for auction by Christie's of London and sold for, well, quite a lot-much more than you or I will ever pay for a bottle of wine. What was so special about this bottle? According to the auction catalog, it had first been purchased by Thomas Jefferson, when he lived in France, but never shipped to the United States. -

Summer 2009 Three Rivers Press Catalog

you better believe it: true stories, truly great reads three rivers press summer 2009 ALL eBOOK PRICING MATCHES THE HARDCOVER/ PAPERBACK COUNTERPART ctaoblenotf ents FRONT LIST 4 AGENTS 70 FOREIGN REPS 71 AUTHOR/TITLE INDEX 72 ORDERING INFORMATION 74 “A deeply satisfying novel…Bohjalian spins a suspenseful tale in which the plot triumphs over any single sorrow.” —Washington Post Book World “Harrowing…ingenious…compelling. That Bohjalian can extract greater truths about faith, hope, and compassion from something as mundane as a diary is testament not only to his skill as a writer but also to the enduring abil - ity of well-written war fiction to stir our deepest emotions.” —los angeles times “[Bohjalian’s] sense of character and place, his skillful plotting, and his clear grasp of this confusing period of history make for a deeply satisfying novel.” —Boston gloBe “While creating suspense, Bohjalian agilely balances the moral ambiguities of war.” — Usa today “A bittersweet story of romance, war, and death, inspired in part by a real diary…Strongly dramatic and full of the heartbreaking horror of war, this novel is Bohjalian at his imaginative best.” —hartford CoUrant Skeletons at the Feast Chris Bohjalian THREE RIVERS PRESS • FEBRUARY A neW york times BESTSELLER A PUBlishers Weekly BESTSELLER A Booksense SELECTION FOREIGN RIGHTS SOLD ACROSS EUROPE AN NBC today SHOW TOP TEN SUMMER READ National Publicity Bestselling author Chris Bohjalian returns 21-City Author Tour with a tale of love and war that multiple Ann Arbor Milwaukee Austin Minneapolis critics have hailed as “harrowing,” “poignant,” Boston New Hampshire Boulder Portland, ME and “nail-biting”—and compared to both The Denver Raleigh Houston San Diego Kite Runner and The Diary of Anne Frank. -

Class, Classification, and Classism: The

CLASS, CLASSIFICATION, AND CLASSISM: THE STORY OF WINE __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication __________________ By Danielle La Fors June 2017 Abstract Through an analysis of the culture industry surrounding the wine trade, the relationship between wine and the greater humanities is examined. Classism, fetishishism, commodification, and even a touch of rhetoric will all be examined through the eyes of the critical cultural lens. In this, it is my finding that without the stories that surround wine, it would be no different from any other commodity. As such, wine, as an artifact, must always tell a story. Is that story in the terroir, in the classist system, or in the consumption of the wine itself? The stories we communicate about wine fetishize the commodity, and influence how people see it as a status symbol. ii CLASS, CLASSIFICATION AND CLASSISM: THE STORY OF WINE By Danielle La Fors Approved: Date: !JliJ$- 6/ljtoJ? Dr. William Lawson iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Lawson of the Communications School at California State University East Bay. The door of Prof. Lawson’s office was always open whenever I had a quick question about my writing, and he was very encouraging about my line of research. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but steered me in the right direction whenever he thought I needed it. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. -

365Ink250.Pdf

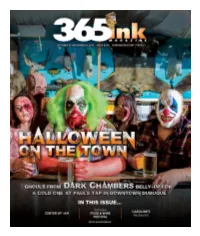

OCTOBER 22–NOVEMBER 4, 2015 ISSUE #250 26 HALLOWEEN EVENTS & DARK CHAMBERS You better have your Halloween costume ready! Scope out this list of events for ghosts and goblins of all ages. We check in with Trent Johnson of Dark Chambers to see what’s new at the Tri-States’ scariest haunted attraction. 22 CENTER OF I AM 32 CAROLINe’S RESTAURANT 24 DUBUQUE FOOD & WINE FESTIVAL EVENTS ARTS NIGHTLIFE COLUMNISTS 4 13 26 32 365INK PRODUCTION STAFF Bryce Parks Publisher, Everything Else Kristina Nesteby Layout Ninja, Designer [email protected] [email protected] Mike Ironside Feature Writer, Photographer [email protected] 365INK ADVERTISING STAFF Kelli Kerrigan Lisa Stevenson [email protected] • 563-581-7014 [email protected] • 563-580-1691 365INK CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Rich Belmont Argosy’s Food For Thought Bob Gelms Bob’s Book Reviews [email protected] [email protected] Matt Booth Mattitude Pam Kress-Dunn Feature Writer [email protected] [email protected] Sara Carpenter Do It Yourself Advice [email protected] SPECIAL THANKS Christy Monk, Gina Siegert, Ryan Decker, Neil Stockel, Kay Kluseman, Ken Kline, Margie Blair, Fran Parks, Julie Steffen, Ron & Jennifer Tigges, Julie Griffin, Mark Dierker, bacon, Steven Schleuning, Tim Brechlin, Roy & Deb Buol, Jeff Lenhart, Gen. Bob Felderman, Dave Haas, Ivonne Simmonds Fals, Christopher Adams, all of our 365 friends and advertisers... and you for reading. Dubuque365/365ink Magazine WHERE’S WANDO 432 Bluff St., Dubuque, IA 52001 •Dubuque365.com • 563-588-4365 We’ve hidden Wando somewhere in this issue of 365ink. Can you find him? All contents © 2015, Community, Incorporated.