UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Wine, Fraud and Expertise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cost of Counterfeits

The Cost of Counterfeits Janice H. Nickel, Henry Sang, Jr. Digital Printing and Imaging Laboratory HP Laboratories Palo Alto HPL-2007-133 August 9, 2007* wine, counterfeiting, Counterfeit goods are having a huge impact on world wide economic health. anti-counterfeiting Accurate estimates on the international counterfeit market are difficult to come by, as counterfeiting is an inherently clandestine process. It is clear however that counterfeiting is reaching into all industries where a profit can be made. The wine industry depends on brand value to command a premium price, which constitutes a prime objective for counterfeiters. Counterfeit wines, not only of premium vintages but also of more modestly priced varieties, have been exposed. We discuss the potential losses to the wine industry, the lure of the premium wine market to counterfeiters, as well as possible actions the industry can take to deter counterfeits. * Internal Accession Date Only Approved for External Publication © Copyright 2007 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. The Cost of Counterfeits Janice H. Nickel, Henry Sang, Jr. Hewlett-Packard Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA 94304 Wine, as with many other products, is becoming a target for counterfeiters. In the globally connected world today, any item that commands a premium price by virtual of brand value can be, and generally is, subject to counterfeiting. To deal with this problem, one needs to understand the risks and costs to the winery and its brand presented by the counterfeiting threat. The wine industry can learn much from efforts in other industries to fight fraud. Hewlett- Packard Company fights to deter counterfeit printer cartridges, computer disc drives, and memory chips on a daily basis. -

Table of Contents White Red Other 2020 2019 2018 2017

2020 LIST Table of Contents 2019 Wines by the Glass .........................................................................................................1 Small Format Listings - Red & White ................................................................................2 White Champagne / Sparkling Wine ......................................................................................... 3 Sparkling Wine / Riesling / Rosé / Pinot Gris (Grigio) ....................................................... 4 Chardonnay / Sauvignon Blanc ....................................................................................... 5 Chardonnay ................................................................................................................. 6 2018 Interesting White Varietals / White Blends ...................................................................... 7 Red Pinot Noir .....................................................................................................................8 Pinot Noir / Merlot / Malbec / Zinfandel .........................................................................9 Syrah / Petite Syrah / Shiraz / New World Blends ............................................................ 10 Cabernet Sauvignon / Cabernet Sauvignon Blends ............................................................ 11 Cabernet Sauvignon / Cabernet Sauvignon Blends ............................................................ 12 Cabernet Sauvignon / Cabernet Franc / Italy .................................................................. -

Varietal Appellation Region Glera/Bianchetta

varietal appellation region 14 prairie organic vodka, fever tree ginger glera/bianchetta veneto, Italy 13 | 52 beer,cucumber, lime merlot/incrocio manzoni veneto, Italy 13 | 52 14 prairie organic gin, rhubarb, lime, basil 14 brooklyn gin, foro dry vermouth, melon de bourgogne 2016 loire, france 10 | 40 bigallet thym liqueur, lemon torrontes 2016 salta, argentina 10 | 40 14 albarino 2015 rias baixas, spain 12 | 48 foro amaro, cointreau, aperol, prosecco, orange dry riesling 2015 finger lakes, new york 13 | 52 14 pinot grigio 2016 alto-adige, italy 14 | 56 milagro tequila, jalapeno, lime, ancho chili salt chardonnay 2014 napa valley, california 14 | 56 14 sauvignon blanc 2015 loire, france 16 | 64 mount gay silver rum, beet, lime 14 calvados, bulleit bourbon, maple syrup, angostura bitters, orange bitters gamay 2016 loire, france 10 | 40 grenache/syrah 2016 provence, france 14 | 56 spain 8 cabernet/merlot 2014 bordeaux, france 10 | 40 malbec 2013 mendoza, argentina 13 | 52 illinois 8 grenache 2014 rhone, france 13 | 52 california 8 sangiovese 2014 tuscany, Italy 14 | 56 montreal 11 pinot noir 2013 central coast, california 16 | 64 massachusetts 10 cabernet sauvignon 2015 paso robles, california 16 | 64 Crafted to remove gluten pinot noir 2014 burgundy, france 17 | 68 massachusetts 7 new york 12 chardonnay/pinot noir NV new york 8 epernay, france 72 new york 9 pinot noir/chardonnay NV ay, france 90 england 10 2014 france 25 (750 ml) friulano 2011 friuli, Italy 38 gruner veltliner 2016 weinviertel, austria 40 france 30 (750 ml) sauvignon -

Celebrity Cruises Proudly Presents Our Extensive Selection of Fine Wines

Celebrity Cruises proudly presents our extensive selection of fine wines, thoughtfully designed to match our globally influenced blend of classic and contemporary cuisine. Our wine list was created to please everyone from the novice wine drinker to the most ardent enthusiast and features over 300 selections. Each wine was carefully reviewed by Celebrity’s team of wine professionals and was selected for its superior quality. We know you share our passion for fine wines and we hope you enjoy your wine experience on Celebrity Cruises. Let our expertly trained sommeliers help guide you on your wine explorations and assist you with any special requests. Cheers! SIGNATURE COCKTAILS $14 BOURBON AND PEACHES MAKER’S MARK BOURBON | PEACH | SIMPLE | LEMON SPICY PASSION KETEL ONE VODKA | PASSION FRUIT | LIME | JALAPEÑO | MINT ULTRAVIOLET BOMBAY SAPHIRE GIN | CRÈME DE VIOLETTE LIQUEUR | SIMPLE FRESH FROM TOKYO GREY GOOSE VODKA | SIMPLE | YUZU | CUCUMBER | BASIL VANILLA MOJITO ZACAPA® 23 RUM | BARREL-AGED CACHAÇA | LIME | VANILLA WANDERING SCOTSMAN BULLEIT RYE | DEMERARA | SCOTCH RINSE BY THE GLASS BUBBLY Brut, Montaudon, Champagne ................................................................................................................................................... 15 Brut, PerrierJouët, ‘Grand Brut,’ Epernay, Champagne .................................................................................................................. 20 Brut Rosè, Domaine Carneros Carneros, California ...................................................................................................................... -

JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3

Book Reviews 423 JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3. Written by Christina Wise and Jason Wise, Produced by Forgotten Man Films, Distributed by Samuel Goldwyn Films, 2018; 1 h 18 min. This is the third in a trilogy of documentaries about the wine world from Jason Wise. The first—Somm, a marvelous film which I reviewed for this Journal in 2013 (Stavins, 2013)–followed a group of four thirty-something sommeliers as they prepared for the exam that would permit them to join the Court of Master Sommeliers, the pinnacle of the profession, a level achieved by only 200 people glob- ally over half a century. The second in the series—Somm: Into the Bottle—provided an exploration of the many elements that go into producing a bottle of wine. And the third—Somm 3—unites its predecessors by combining information and evocative scenes with a genuine dramatic arc, which may not have you on pins and needles as the first film did, but nevertheless provides what is needed to create a film that should not be missed by oenophiles, and many others for that matter. Before going further, I must take note of some unfortunate, even tragic events that have recently involved the segment of the wine industry—sommeliers—featured in this and the previous films in the series. Five years after the original Somm was released, a cheating scandal rocked the Court of Master Sommeliers, when the results of the tasting portion of the 2018 exam were invalidated because a proctor had disclosed confidential test information the day of the exam. -

Larkmead Vineyards: Single Site, Multiple Terroirs

LARKMEAD VINEYARDS: SINGLE SITE, MULTIPLE TERROIRS ELIN MC COY, DECANTER, AUGUST 5, 2019 Napa Valley had a rich wine history long before Prohibition, and three of the most celebrated wineries from that bygone era – Inglenook, Beaulieu Vineyards and Beringer – are still famous today. Family-owned Larkmead in Calistoga is a fourth, founded 125 years ago, but, jokes winemaker Dan Petroski, ‘It’s the one you’ve never heard of.’ Larkmead’s modern story began about 20 years ago, and it’s now making some of Napa’s top Cabernets and getting some serious recognition. So when Petroski invited me to a vertical tasting of six vintages of The Lark – the winery’s top Cabernet – that he was staging for collectors before the big-spend Napa wine auction, I emailed back: ‘Yes!’ On the warm summer day, bees were buzzing in the garden around the porch of the sleek, chic white farmhouse and winery designed by architect Howard Backen. The setting is idyllic: you look out on vineyards that stretch across the valley floor from Highway 29 on the west nearly to Silverado Trail on the east. ‘The soils,’ says Petroski, ‘are very diverse. They’re like a snapshot of the whole Napa Valley.’ Before the official tasting, he lined up three early vintages of The Lark and a couple of bottles of Solari, a Cabernet made from the estate’s oldest vines, for me to sample in the bright and airy farmhouse. HISTORY Cam and Kate Solari Baker, the owners, dropped by to reveal amusing tidbits about the winery’s history, which starts with the first owner, colourful Firebelle Lil, who drank bourbon, smoked cigars, and came up with the name Larkmead. -

737 DCDBKURT1 Trial 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 1 SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK 2 ------X 2 3 UNITED STATES of AMERICA, 3 4 V

737 DCDBKURT1 Trial 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 1 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK 2 ------------------------------x 2 3 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 3 4 v. S1 12 Cr. 376(RMB) 4 5 RUDY KURNIAWAN, a/k/a "Dr. Conti," 5 a/k/a "Mr. 47," 6 6 Defendant. 7 7 ------------------------------x 8 December 13, 2013 8 9:07 a.m. 9 9 Before: 10 10 HON. RICHARD M. BERMAN, 11 11 District Judge 12 13 APPEARANCES 13 14 PREET BHARARA, 14 United States Attorney for the 15 Southern District of New York 15 JASON HERNANDEZ, 16 JOSEPH FACCIPONTI, 16 Assistant United States Attorneys 17 17 WESTON, GARROU & MOONEY 18 Attorneys for defendant 18 BY: JEROME MOONEY 19 19 VERDIRAMO & VERDIRAMO, P.A. 20 Attorneys for defendant 20 BY: VINCENT S. VERDIRAMO 21 21 - also present - 22 22 Ariel Platt, Government paralegal 23 Bibi Hayakawa, Government paralegal 23 24 SA James Wynne, FBI 24 SA Adam Roeser, FBI 25 SOUTHERN DISTRICT REPORTERS, P.C. (212) 805-0300 738 DCDBKURT1 Trial 1 (Trial resumed) 2 (In open court; jury present). 3 THE COURT: Okay, everybody. Nice to see you. Please 4 be seated and we'll start. 5 We'll have the next government witness. 6 MR. HERNANDEZ: Government calls William Koch. 7 THE COURT: Okay. 8 THE DEPUTY CLERK: Sir, please remain standing. 9 WILLIAM KOCH, 10 called as a witness by the Government, 11 having been duly sworn, testified as follows: 12 THE DEPUTY CLERK: Can you state your name for the 13 record, please? 14 THE WITNESS: William Koch, spelled K-O-C-H. -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 56/Thursday, March 22, 2012/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 56 / Thursday, March 22, 2012 / Rules and Regulations 16671 litigation, establish clear legal DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY • The United States; standards, and reduce burden. • A State; Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade • Two or no more than three States Executive Order 13563 Bureau which are all contiguous; The Department of State has • A county; considered this rule in light of 27 CFR Part 4 • Two or no more than three counties Executive Order 13563, dated January in the same State; or [Docket No. TTB–2010–0007; T.D. TTB–101; • A viticultural area as defined in 18, 2011, and affirms that this regulation Re: Notice No. 110] is consistent with the guidance therein. § 4.25(e). RIN 1513–AB58 Section 4.25(b)(1) states that an Executive Order 13175 American wine is entitled to an Labeling Imported Wines With The Department has determined that appellation of origin other than a Multistate Appellations this rulemaking will not have tribal multicounty or multistate appellation, implications, will not impose AGENCY: Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and or a viticultural area, if, among other substantial direct compliance costs on Trade Bureau, Treasury. requirements, at least 75 percent of the Indian tribal governments, and will not ACTION: Final rule; Treasury decision. wine is derived from fruit or agricultural preempt tribal law. Accordingly, products grown in the appellation area Executive Order 13175 does not apply SUMMARY: The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax indicated. Use of an appellation of to this rulemaking. and Trade Bureau is amending the wine origin comprising two or no more than labeling regulations to allow the three States which are all contiguous is Paperwork Reduction Act labeling of imported wines with allowed under § 4.25(d) if: This rule does not impose any new multistate appellations of origin. -

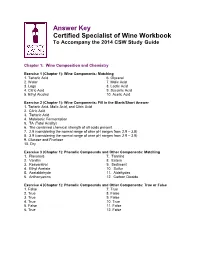

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Glossary of Wine Terms - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 4/28/10 12:05 PM

Glossary of wine terms - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 4/28/10 12:05 PM Glossary of wine terms From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The glossary of wine terms lists the definitions of many general terms used within the wine industry. For terms specific to viticulture, winemaking, grape varieties, and wine tasting, see the topic specific list in the "See Also" section below. Contents: Top · 0–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A A.B.C. Acronym for "Anything but Chardonnay" or "Anything but Cabernet". A term conceived by Bonny Doon's Randall Grahm to describe wine drinkers interest in grape varieties A.B.V. Abbreviation of alcohol by volume, generally listed on a wine label. AC Abbreviation for "Agricultural Cooperative" on Greek wine labels and for Adega Cooperativa on Portuguese labels. Adega Portuguese wine term for a winery or wine cellar. Altar wine The wine used by the Catholic Church in celebrations of the Eucharist. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_wine_terms Page 1 of 35 Glossary of wine terms - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 4/28/10 12:05 PM A.O.C. Abbreviation for Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée, (English: Appellation of controlled origin), as specified under French law. The AOC laws specify and delimit the geography from which a particular wine (or other food product) may originate and methods by which it may be made. The regulations are administered by the Institut National des Appellations d'Origine (INAO). A.P. -

N/V Fizzy & Uplifting

FIZZY & UPLIFTING TYPE VINTAGE PRODUCER APPELLATION GLASS BOTTLE CAVA N/V Mercat, Brut Barcelona, Spain 12 48 CHAMPAGNE N/V Laurent Perrier ‘Grand Siècle’, Brut Champagne, France 300 CHAMPAGNE N/V Sabine Godmé, Brut Champagne 1er Cru, France 95 CHAMPAGNE 2014 Laurent Benard, Extra Brut Champagne, France 142 CAVA 2016 Alta Alella ‘Mirgin’ Gran Reserva, Catalonia, Spain 75 Brut Nature CRÈMANT N/V May Georges, Brut Loire, France 18 72 CRÈMANT N/V May Georges, Brut Loire, France 140 CRÈMANT N/V Henri Champliau, Brut Burgundy, France 65 PET NAT 2019 La Grange de L’Oncle, Brut Alsace, France 75 GRÜNER VELTLINER N/V Szigeti, Brut Burgenland, Austria 55 FRANCIACORTA N/V Berlucchi ‘61, Brut Franciacorta, Lombardy, Italy 105 CHAMPAGNE N/V Ayala, Brut Champagne, France 105 ROSÉ OF SANGIOVESE 2015 Baracchi, Brut Italy 98 ROSÉ CHAMPAGNE N/V Billecart Salmon, Brut, 1.5L Champagne, France 420 ROSÉ CAP CLASSIQUE N/V Krone, Brut Western Cape, South Africa 60 ROSÉ CHAMPAGNE N/V Deutz, Brut, 375mL Champagne, France 75 COOL & ADVENTUROUS TYPE VINTAGE PRODUCER APPELLATION GLASS BOTTLE VERMENTINO 2020 Vigne Surrau ‘Limizzani’ Vermentino di Gallura, 12 48 Sardinia, Italy PINOT GRIGIO 2019 Tiefenbrunner Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy 12 48 PINOT GRIS 2017 Lemelson Willamette Valley, OR 56 SAUVIGNON BLANC 2020 Hubert Brochard ‘Tradition’ Sancerre, France 80 SAUVIGNON BLANC 2020 Astrolabe Marlborough, New Zealand 48 SAUVIGNON BLANC 2019 Matanzas Creek Sonoma County, CA 13 52 RIESLING 2019 Von Buhl ‘Bone Dry’ Pfalz, Germany 68 PECORINO 2018 Ferzo Abruzzo, Italy 53 FURMINT -

Neutrino, Wine and Fraudulent Business Practices

Neutrino, wine and fraudulent business practices Michael S. Pravikoff*, Philippe Hubert and Hervé Guegan CENBG (CNRS/IN2P3 & University of Bordeaux), 19 chemin du Solarium, CS 10120, F-33175 Gradignan cedex, France Abstract The search for the neutrino and its properties, to find if it is a Dirac or Majorana particle, has kept physicists and engineers busy for a long time. The Neutrino Ettore Majorana Observatory (NEMO) experiment and its latest demonstrator, SuperNEMO, demanded the development of high-purity low-background γ- ray detectors to select radioactive-free components for the demonstrator. A spin-off of these detectors is inter-disciplinary measurements, and it led to the establishment of a reference curve to date wines. In turn, this proved to be an effective method to fight against wine counterfeiters. 1 Introduction Over the last few decades, demand for fine wines has soared tremendously. Especially some particular vintages, notably from famous wine areas, lead to stupendous market prices, be it between private col- lectors as well as through wine merchants and/or auction houses. The love of wine was not and is still not the main factor in this uprising business: wine has become or maybe always was a financial asset. No surprise that this lured many people to try to make huge and easy profit by forging counterfeited bottles of the most prestigious - and expensive - "Grands Crus". But for old or very old fine wines, experts are at loss because of the complexity of a wine, the lack of traceability and so on. By measuring the minute quantity of radioactivity contained in the wine without opening the bottle, a method has been developed to counteract counterfeiters in most cases.