Class, Classification, and Classism: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does Wine Have a Place in Kant's Theory of Taste?1

Does Wine Have a Place in Kant’s Theory of Taste?1 Rachel Cristy, Princeton University Kant’s own answer to my title question is “no.” One can make of a wine the merely subjective judgment that it is agreeable, never the universally valid judgment that it is beautiful. Here is Kant’s only remark on wine in the Critique of the Power of Judgment: With regard to the agreeable, everyone is content that his judgment, which he grounds on a private feeling, and in which he says of an object that it pleases him, be restricted merely to his own person. Hence he is perfectly happy if, when he says that sparkling wine from the Canaries is agreeable, someone else should improve his expression and remind him that he should say “It is agreeable to me”; and this is so not only in the case of the taste of the tongue, palate, and throat, but also in the case of that which may be agreeable to someone’s eyes and ears. (KU §7, 5: 212) Here is Kant’s explanation for why wine can’t be judged beautiful: “Aesthetic judgments can be divided into empirical and pure. The first are those which assert agreeableness or disagreeableness, the second those which assert beauty of an object… the former are judgments of sense (material aesthetic judgments), the latter (as formal) are alone proper judgments of taste” (§14, 5: 223). Not only flavors and aromas, but also “mere color, e.g., the green of a lawn” and “mere tone…say that of a violin” are relegated to judgments of agreeableness, because they “have as their ground merely the matter of the representations, namely mere sensation” (§14, 5: 224). -

Celebrity Cruises Proudly Presents Our Extensive Selection of Fine Wines

Celebrity Cruises proudly presents our extensive selection of fine wines, thoughtfully designed to match our globally influenced blend of classic and contemporary cuisine. Our wine list was created to please everyone from the novice wine drinker to the most ardent enthusiast and features over 300 selections. Each wine was carefully reviewed by Celebrity’s team of wine professionals and was selected for its superior quality. We know you share our passion for fine wines and we hope you enjoy your wine experience on Celebrity Cruises. Let our expertly trained sommeliers help guide you on your wine explorations and assist you with any special requests. Cheers! SIGNATURE COCKTAILS $14 BOURBON AND PEACHES MAKER’S MARK BOURBON | PEACH | SIMPLE | LEMON SPICY PASSION KETEL ONE VODKA | PASSION FRUIT | LIME | JALAPEÑO | MINT ULTRAVIOLET BOMBAY SAPHIRE GIN | CRÈME DE VIOLETTE LIQUEUR | SIMPLE FRESH FROM TOKYO GREY GOOSE VODKA | SIMPLE | YUZU | CUCUMBER | BASIL VANILLA MOJITO ZACAPA® 23 RUM | BARREL-AGED CACHAÇA | LIME | VANILLA WANDERING SCOTSMAN BULLEIT RYE | DEMERARA | SCOTCH RINSE BY THE GLASS BUBBLY Brut, Montaudon, Champagne ................................................................................................................................................... 15 Brut, PerrierJouët, ‘Grand Brut,’ Epernay, Champagne .................................................................................................................. 20 Brut Rosè, Domaine Carneros Carneros, California ...................................................................................................................... -

JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3

Book Reviews 423 JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3. Written by Christina Wise and Jason Wise, Produced by Forgotten Man Films, Distributed by Samuel Goldwyn Films, 2018; 1 h 18 min. This is the third in a trilogy of documentaries about the wine world from Jason Wise. The first—Somm, a marvelous film which I reviewed for this Journal in 2013 (Stavins, 2013)–followed a group of four thirty-something sommeliers as they prepared for the exam that would permit them to join the Court of Master Sommeliers, the pinnacle of the profession, a level achieved by only 200 people glob- ally over half a century. The second in the series—Somm: Into the Bottle—provided an exploration of the many elements that go into producing a bottle of wine. And the third—Somm 3—unites its predecessors by combining information and evocative scenes with a genuine dramatic arc, which may not have you on pins and needles as the first film did, but nevertheless provides what is needed to create a film that should not be missed by oenophiles, and many others for that matter. Before going further, I must take note of some unfortunate, even tragic events that have recently involved the segment of the wine industry—sommeliers—featured in this and the previous films in the series. Five years after the original Somm was released, a cheating scandal rocked the Court of Master Sommeliers, when the results of the tasting portion of the 2018 exam were invalidated because a proctor had disclosed confidential test information the day of the exam. -

Wine Regulations 2005

S. I. of 2005 NATIONAL AGENCY FOR FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION AND CONTROL ACT 1993 (AS AMENDED) Wine Regulations 2005 Commencement: In exercise of the powers conferred on the Governing Council of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) by Sections 5 and 29 of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control Act 1993, as amended, and of all the powers enabling it in that behalf, THE GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE NATIONAL AGENCY FOR FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION AND CONTROL with the approval of the Honourable Minister of Health hereby makes the following Regulations:- Prohibition: 1. No person shall manufacture, import, export, advertise, sell or distribute wine specified in Schedule I to these Regulations in Nigeria unless it has been registered in accordance with the provisions of these regulations. Use and Limit of 2. The use and limits of any food additives or food food additives. colours in the manufacture of wine shall be as approved by the Agency. Labelling. 3. (1) The labeling of wine shall be in accordance with the Pre-packaged Food (Labelling) Regulations 2005. (2) Notwithstanding Regulation 3 (i) of these Regulations, wines that contain less than 10 percent absolute alcohol by volume shall have the ‘Best Before’ date declared. 1 Name of Wine 4. (1) The name of every wine shall indicate the to indicate the accurate nature. nature etc. (2) Where a name has been established for the wine in these Regulations, such a name shall only be used. (3) Where no common name exists for the wine, an appropriate descriptive name shall be used. -

James Suckling Biography

James Suckling Biography James Suckling is one of today’s leading wine critics, whose views are read and respected by wine lovers, serious wine collectors, and the wine trade worldwide. He is currently the wine editor for Asia Tatler and its nine luxury magazines in the region, including Hong Kong Tatler, China Tatler, Singapore Tatler, and Thailand Tatler. However, most of his time is spent working for his own website, JamesSuckling.com, as well as promoting his 100 Points wine glass with Lalique, the famous French crystal house. Suckling spent nearly 30 years as Senior Editor and European Bureau Chief of The Wine Spectator, and as European Editor of Cigar Aficionado. On his departure from the magazines, Forbes called the Los Angeles-born writer “one of the world’s most powerful wine critics.” In late 2010, Suckling launched JamesSuckling.com, a site that evolved from him seeing a need for wine to be communicated in a more modern way. The site offers subscribers high-definition video content hosted by Suckling that reports on and rates the best wines from around the world, with a focus on Italy and Bordeaux. Video tastings and interviews conducted in vineyards and cellars with winemakers give viewers a firsthand account of the wines, and allow for a more spontaneous style. The site attracts viewers from over 110 countries, with the largest audiences in North America, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, Australia, Italy, and France. His first documentary film, “Cigars: The Heart and Soul of Cuba,” was released in autumn 2011 to much acclaim. It was screened in December 2011 during the 33rd Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana, Cuba, and was officially selected for the 15th Annual Sonoma Film Festival in Sonoma, Calif. -

737 DCDBKURT1 Trial 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 1 SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK 2 ------X 2 3 UNITED STATES of AMERICA, 3 4 V

737 DCDBKURT1 Trial 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 1 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK 2 ------------------------------x 2 3 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 3 4 v. S1 12 Cr. 376(RMB) 4 5 RUDY KURNIAWAN, a/k/a "Dr. Conti," 5 a/k/a "Mr. 47," 6 6 Defendant. 7 7 ------------------------------x 8 December 13, 2013 8 9:07 a.m. 9 9 Before: 10 10 HON. RICHARD M. BERMAN, 11 11 District Judge 12 13 APPEARANCES 13 14 PREET BHARARA, 14 United States Attorney for the 15 Southern District of New York 15 JASON HERNANDEZ, 16 JOSEPH FACCIPONTI, 16 Assistant United States Attorneys 17 17 WESTON, GARROU & MOONEY 18 Attorneys for defendant 18 BY: JEROME MOONEY 19 19 VERDIRAMO & VERDIRAMO, P.A. 20 Attorneys for defendant 20 BY: VINCENT S. VERDIRAMO 21 21 - also present - 22 22 Ariel Platt, Government paralegal 23 Bibi Hayakawa, Government paralegal 23 24 SA James Wynne, FBI 24 SA Adam Roeser, FBI 25 SOUTHERN DISTRICT REPORTERS, P.C. (212) 805-0300 738 DCDBKURT1 Trial 1 (Trial resumed) 2 (In open court; jury present). 3 THE COURT: Okay, everybody. Nice to see you. Please 4 be seated and we'll start. 5 We'll have the next government witness. 6 MR. HERNANDEZ: Government calls William Koch. 7 THE COURT: Okay. 8 THE DEPUTY CLERK: Sir, please remain standing. 9 WILLIAM KOCH, 10 called as a witness by the Government, 11 having been duly sworn, testified as follows: 12 THE DEPUTY CLERK: Can you state your name for the 13 record, please? 14 THE WITNESS: William Koch, spelled K-O-C-H. -

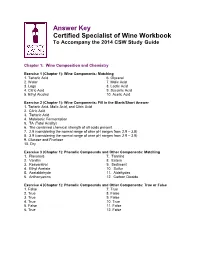

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (Nafdac) Wine Regulations 2019

NATIONAL AGENCY FOR FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION AND CONTROL (NAFDAC) WINE REGULATIONS 2019 1 ARRANGEMENT OF REGULATIONS Commencement 1. Scope 2. Prohibition 3. Use and Limit of food additives 4. Categories of Grape Wine 5. Vintage dating 6. Varietal designations 7. Sugar content and sweetness descriptors 8. Single-vineyard designated wines 9. Labelling 10. Name of Wine to indicate the nature 11. Traditional terms of quality 12. Advertisement 13. Penalty 14. Forfeiture 15. Interpretation 16. Repeal 17. Citation 18. Schedules 2 Commencement: In exercise of the powers conferred on the Governing Council of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) by sections 5 and 30 of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control Act Cap NI Laws of the Federation of Nigeria (LFN) 2004 and all powers enabling it in that behalf, the Governing Council of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control with the approval of the Honourable Minister of Health hereby makes the following Regulations:- 1. Scope These Regulations shall apply to wine manufactured, imported, exported, advertised, sold, distributed or used in Nigeria. 2. Prohibition: No person shall manufacture, import, export, advertise, sell or distribute wine specified in Schedule I to these Regulations in Nigeria unless it has been registered in accordance with the provisions of these Regulations. 3. Use and Limit of food additives. (1) The use and limits of any food additives or food colors in the manufacture of wine shall be as approved by the Agency. (2) Where sulphites are present at a level above 10ppm, it shall require a declaration on the label that it contains sulphites. -

Glossary of Wine Terms - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 4/28/10 12:05 PM

Glossary of wine terms - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 4/28/10 12:05 PM Glossary of wine terms From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The glossary of wine terms lists the definitions of many general terms used within the wine industry. For terms specific to viticulture, winemaking, grape varieties, and wine tasting, see the topic specific list in the "See Also" section below. Contents: Top · 0–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A A.B.C. Acronym for "Anything but Chardonnay" or "Anything but Cabernet". A term conceived by Bonny Doon's Randall Grahm to describe wine drinkers interest in grape varieties A.B.V. Abbreviation of alcohol by volume, generally listed on a wine label. AC Abbreviation for "Agricultural Cooperative" on Greek wine labels and for Adega Cooperativa on Portuguese labels. Adega Portuguese wine term for a winery or wine cellar. Altar wine The wine used by the Catholic Church in celebrations of the Eucharist. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_wine_terms Page 1 of 35 Glossary of wine terms - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 4/28/10 12:05 PM A.O.C. Abbreviation for Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée, (English: Appellation of controlled origin), as specified under French law. The AOC laws specify and delimit the geography from which a particular wine (or other food product) may originate and methods by which it may be made. The regulations are administered by the Institut National des Appellations d'Origine (INAO). A.P. -

Neutrino, Wine and Fraudulent Business Practices

Neutrino, wine and fraudulent business practices Michael S. Pravikoff*, Philippe Hubert and Hervé Guegan CENBG (CNRS/IN2P3 & University of Bordeaux), 19 chemin du Solarium, CS 10120, F-33175 Gradignan cedex, France Abstract The search for the neutrino and its properties, to find if it is a Dirac or Majorana particle, has kept physicists and engineers busy for a long time. The Neutrino Ettore Majorana Observatory (NEMO) experiment and its latest demonstrator, SuperNEMO, demanded the development of high-purity low-background γ- ray detectors to select radioactive-free components for the demonstrator. A spin-off of these detectors is inter-disciplinary measurements, and it led to the establishment of a reference curve to date wines. In turn, this proved to be an effective method to fight against wine counterfeiters. 1 Introduction Over the last few decades, demand for fine wines has soared tremendously. Especially some particular vintages, notably from famous wine areas, lead to stupendous market prices, be it between private col- lectors as well as through wine merchants and/or auction houses. The love of wine was not and is still not the main factor in this uprising business: wine has become or maybe always was a financial asset. No surprise that this lured many people to try to make huge and easy profit by forging counterfeited bottles of the most prestigious - and expensive - "Grands Crus". But for old or very old fine wines, experts are at loss because of the complexity of a wine, the lack of traceability and so on. By measuring the minute quantity of radioactivity contained in the wine without opening the bottle, a method has been developed to counteract counterfeiters in most cases. -

Wine Fraud: in Defense of Auction Houses

Wine Fraud: In Defense of Auction Houses Home | About Us | Find a Store | Wine Regions | Site Map Pro Version | GBP Change Currency | Help | Mobile Site Magazine Newsletter Home (Magazine) > Features > Wine Fraud: In Defense of Auction Houses Departments: Wine Fraud: In Defense of Auction Houses Recent Stories The Wire An English Brewer in Just In Normandy is Conquering Features the French Brewer shows the French Architectural Report what beer should really taste Bill of Fare like. Q&A Posted Friday, 10-Aug-2012 Unusual Suspects Receptions and Dinners Mark Julia Child's 100th When We First Met Birthday © Fotolia.com Case Study Gastronomes throughout North America celebrate Science Corner An examination of fraud in the fine-wine industry. By Maureen Downey. great chef's upcoming The Bookshelf centenary. Posted Friday, 10-Aug-2012 Critics Pick Posted Thursday, 09-Aug-2012 The issue of wine fraud in the fine- and rare-wine industry has exploded A Real French Experience: in the media since the March arrest of alleged counterfeiter Rudy Picking Grapes Kurniawan in the United States. Along with some other industry insiders, The lowdown on getting I've been waiting for the matter to be tackled for more than a decade. amongst the vines in France. However, I wasn’t expecting the kind of response that we've seen Posted Friday, 10-Aug-2012 surrounding the Kurniawan affair: frenzied enthusiasts, collectors, wine- forum users and the occasional journalist have grabbed the wrong end of Harvest Brings Smiles to the stick. When it comes to the most frequent sources of fake wine and French Growers' Faces the health of the United States wine-auction market, false notions are First indications are the rampant. -

Colour Evolution of Rosé Wines After Bottling

Colour Evolution of Rosé Wines after Bottling B. Hernández, C. Sáenz*, C. Alberdi, S. Alfonso and J.M. Diñeiro Departamento de Física, Universidad Pública de Navarra, Campus Arrosadía, 31006 Pamplona, Navarra (SPAIN) Submitted for publication: July 2010 Accepted for publication: September 2010 Key words: Colour appearance, wine colour, rosé wine, colour measurement, colour evolution This research reports on the colour evolution of six rosé wines during sixteen months of storage in the bottle. Colour changes were determined in terms of CIELAB colour parameters and in terms of the common colour categories used in visual assessment. The colour measurement method reproduces the visual assessment conditions during wine tasting with respect to wine sampler, illuminating source, observing background and sample-observer geometry. CIELAB L*, a*, b*, C* and hab colour coordinates were determined at seven different times (t = 0, 20, 80, 153, 217, 300 and 473 days). The time evolution of colour coordinate values was studied using models related to linear, quadratic and exponential rise to a maximum. Adjusted R2, average standard error and CIELAB ΔE* colour difference were used to compare models and evaluate their performance. For each colour coordinate, the accuracy of model predictions was similar to the standard deviation associated with a single measurement. An average ΔE* = 0.92 with a 90 percentile value ΔE*90% = 1.50 was obtained between measured and predicted colour. These values are smaller than human colour discrimination thresholds. The classification into colour categories at different times depends on the wine sample. It was found that all wines take three to four months to change from raspberry to strawberry colour and seven to eight months to reach the redcurrant category.