For Peer Review Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Election 2006

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library RESEARCH BRIEF Information analysis and advice for the Parliament 16 November 2006, no. 3, 2006–07, ISSN 1832-2883 Queensland Election 2006 The Queensland election of September 2006 saw the Beattie Labor Government win a fourth term of office, continuing the longest period of ALP government in the state since 1957. The Coalition parties’ share of the vote puts them within reach of victory, but the way in which they work towards the next election—particularly in the area of policy development—will be crucial to them if they are to succeed. Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Section Stephen Barber, Statistics and Mapping Section Contents Executive summary ................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................ 2 An election is called .................................................. 2 The Government’s travails............................................ 2 The Coalition ..................................................... 4 Might the Government be defeated? ..................................... 6 Over before it started? ................................................. 6 Party prospects ...................................................... 7 The Coalition parties ................................................ 7 The Government ................................................... 8 Campaigning........................................................ 8 The Government................................................ -

An Industry Policy for Queensland Boreham & Salisbury TJ Ryan

policy brief An Industry Policy for Queensland Professor Paul Boreham Emeritus Professor Institute for Social Science Research The University of Queensland Contact: https://www.issr.uq.edu.au/staff/boreham-paul Dr Chris Salisbury Research Associate Institute for Social Science Research The University of Queensland Contact: http://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/10581 An Industry Policy for Queensland 1 TJ Ryan Foundation Policy Brief 02 2 Aug 2016 An Industry Policy for Queensland Paul Boreham & Chris Salisbury any countries are pursuing innovation-led industry policies engaging in long-run M strategic investments to create and shape industry trajectories rather than just responding to problems of industry decline. This has required public agencies to lead and direct the creation of new technological opportunities and innovations. The predictable response from bureaucrats and politicians steeped in economic liberalism (that industry policy is not an appropriate instrument of public policy) must face rebuttal as both economically ill-informed and unjustified by evidence. This paper provides an overview of the key issues exemplifying the development of industry policy in many of the advanced economies and draws an outline map of how they might be applied to the Queensland economy. Introduction The structure of the Queensland economy has changed significantly in the past decade. Manufacturing, as a component of Gross State Product, has declined from 10.4 per cent in 2004-5 to 7.2 per cent in 2014-5. The sector’s contribution to State employment has declined from 10 per cent to 7.2 per cent. Likewise, mining’s contribution to Gross State Product has fallen from a peak of 14.8 per cent in 2008-9 to 7.3 per cent in 2014-5 while its contribution to employment has increased only slightly from 2 per cent to 2.8 per cent. -

Media Release Anna Bligh Appointed CEO of Australian Bankers

Level 3, 56 Pitt Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia +61 2 8298 0417 @austbankers bankers.asn.au Media Release Anna Bligh appointed CEO of Australian Bankers’ Association Sydney, 17 February 2017: The Chairman of the Australian Bankers’ Association, Andrew Thorburn, today announced the appointment of Anna Bligh to lead the ABA as it continues its work to strengthen trust and confidence in banking and deliver better outcomes for customers. “We are excited to appoint Anna as Chief Executive Officer at such a pivotal time for our industry,” Mr Thorburn said. “Anna’s focus will firmly be on the culture within banking and lifting respect for our profession; creating a strong vision for customers and on how our industry responds and leads on regulatory reform. “As I’ve met with Anna I’ve seen the leadership, values and accountability she will bring to the role – and a willingness to confront and challenge the industry to continually improve. “Anna has a track record of community service and a strong ability to connect with people. She is highly regarded and respected by community, political and business leaders and understands the need for all stakeholders to work together to deliver the best outcome for customers.” Mr Thorburn added: “Australia has a world-class banking system and there is more we can do to be better for customers and demonstrate the role banks play for them, the broader community and the Australian economy. “We have also heard the message from customers and from the public, and the industry is serious about change. The appointment of Anna demonstrates our commitment to this.” Ms Bligh has more than 30 years’ experience in public service, initially with community organisations, before entering the Queensland Parliament in 1995. -

Paper Presented by the Hon. Peter Wellington MP

UI1SFTJEJOH0⒏DFST`$MFSLT` $POGFSFODF 4ZEOFZ +VMZ l4USJLJOHUIF#BMBODF*NQBSUJBMJUZBOE SFQSFTFOUBUJPOJOUIF2VFFOTMBOEQBSMJBNFOUz 1BQFSCZ)PO1FUFS8FMMJOHUPO.1 4QFBLFSPGUIF-FHJTMBUJWF"TTFNCMZ 2VFFOTMBOE1BSMJBNFOU This aim of this paper is to describe the ways in which the Speakership of the Queensland Parliament currently operates, to consider the ways in which this differs from the traditional Westminster style Parliament and indeed from previous Queensland Parliaments, and to reflect on the particular demands placed on the Speakers of small Parliaments. The Parliamentary Speaker and tradition The tradition of Speakership in the Westminster parliamentary system is a long and enduring one, commencing with the appointment of the first British Speaker, Sir Thomas Hungerford, who was appointed in 1377. From these earliest times, the Speaker has been the mouthpiece or representative of the House, speaking on behalf of the House in communicating its deliberations and decisions, to the monarchy, the Executive and also others. The Speaker represents, in a very real sense, the right of freedom of speech in the Parliament, which was hard won from a monarchical Executive centuries ago. The Parliament must constantly be prepared to maintain its right of…freedom of speech, without fear or favour.1 Amongst the numerous powers, responsibilities and functions vested in Speakers via the constitution, standing orders and conventions, and in addition to being the spokesperson of the House, the main functions of the Speaker are to preside over the debates of the -

For a Discussion of the Australian "Hydraulic Dreaming"

http://epress.anu.edu.au/anzsog/auc/html/ch06s03.html Extract From: Australia Under Construction Nation-building past, present and future Edited by John Butcher Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Australia under construction : nation-building : past, present and future / editor, John Butcher. ISBN: 9781921313776 (pbk.) 9781921313783 (online) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Federal government--Australia. Politics and culture--Australia. Australia--Social conditions. Australia--Economic conditions. Australia--Politics and government. Other Authors/Contributors: Butcher, John. Australia and New Zealand School of Government. Dewey Number: 320.994 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. Cover design by John Butcher. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press 6. Populate, parch and panic: two centuries of dreaming about nation-building in inland Australia Introduction This chapter represents one facet of a more extensive research project on the historical development and future prospects of the Australian inland, especially the area that lies between the Great Dividing Range and the deserts of Central Australia. The question I will attempt to answer here is that of why a grandiose ‘nation-building’ solution to the perceived problems of the inland has retained a significant presence in public debate for more than seven decades, even though it has repeatedly and convincingly proved to be impractical and financially unviable. -

Freedom of Information – the Right to Know (UNESCO)

United Nations [ Cultural Organization FREEDOM OF INFORMATION: WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY 2010 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization FREEDOM OF INFORMATION: WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY 2010 © UNESCO 2011 All rights reserved http://www.unesco.org/webworld Cover photo: words carved into the sandstone portal of the Forgan Smith Building at the University of Queensland Photo credit: University of Queensland The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this document do not imply the expression of any opin- ion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this document and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization Typeset by UNESCO CI-2011/WS/1 Rev. CONTENTS MESSAGE by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO 5 FOREWORD by Janis Karklins, Assistant Director-General for Communication and 6 Information, UNESCO INTRODUCTION by Michael Bromley, Head of the School of Journalism and Communication, 7 University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia UNESCO CONCEPT NOTE 13 FOR WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY 2010 CONFERENCE OPENING CEREMONY WELCOME ADDRESSES 19 Maurie McNarn, AO 19 Acting Vice-Chancellor and Executive Director (Operations) The University of Queensland Hon. Cameron Dick, MP, 21 Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations, State Government of Queensland H.E. Ms Penelope Wensley, AO 23 Governor of Queensland The University of Queensland Centenary Oration 25 Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO PART 1. -

Hon. Cameron Dick

Speech by Hon. Cameron Dick MEMBER FOR GREENSLOPES Hansard Wednesday, 22 April 2009 MAIDEN SPEECH Hon. CR DICK (Greenslopes—ALP) (Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations) (7.30 pm): I start tonight by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land where this parliament stands who have served and nurtured this land for centuries. I pay tribute to them and their great role in our history. It is in this reflection of history that I begin tonight. In December 1862, three short years after the birth of our great state, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year, the sailing ship Conway arrived in the small Queensland settlement then known as Moreton Bay. History little records the fate of the Conway, its passengers and its crew, but one thing is known about that day in December 1862: that is the day my family arrived in Queensland and began its Queensland journey. Almost 150 years later, that journey has taken me to this place, the Queensland parliament. I stand tonight as a representative of the people in our state’s legislature, not only as a fifth-generation Queenslander but also with great humility and honour as a son of the state seat of Greenslopes, the electorate I now serve as a member of parliament. My first thanks this evening go to those people who make up the community of Greenslopes. It is a wonderful and diverse community and I look forward to serving them to the best of my ability. This electorate is very dear to my heart. It was at Holland Park, in the Greenslopes electorate, that I was raised as a boy. -

1 Heat Treatment This Is a List of Greenhouse Gas Emitting

Heat treatment This is a list of greenhouse gas emitting companies and peak industry bodies and the firms they employ to lobby government. It is based on data from the federal and state lobbying registers.* Client Industry Lobby Company AGL Energy Oil and Gas Enhance Corporate Lobbyists registered with Enhance Lobbyist Background Limited Pty Ltd Corporate Pty Ltd* James (Jim) Peter Elder Former Labor Deputy Premier and Minister for State Development and Trade (Queensland) Kirsten Wishart - Michael Todd Former adviser to Queensland Premier Peter Beattie Mike Smith Policy adviser to the Queensland Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, LHMU industrial officer, state secretary to the NT Labor party. Nicholas James Park Former staffer to Federal Coalition MPs and Senators in the portfolios of: Energy and Resources, Land and Property Development, IT and Telecommunications, Gaming and Tourism. Samuel Sydney Doumany Former Queensland Liberal Attorney General and Minister for Justice Terence John Kempnich Former political adviser in the Queensland Labor and ACT Governments AGL Energy Oil and Gas Government Relations Lobbyists registered with Government Lobbyist Background Limited Australia advisory Pty Relations Australia advisory Pty Ltd* Ltd Damian Francis O’Connor Former assistant General Secretary within the NSW Australian Labor Party Elizabeth Waterland Ian Armstrong - Jacqueline Pace - * All lobbyists registered with individual firms do not necessarily work for all of that firm’s clients. Lobby lists are updated regularly. This -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

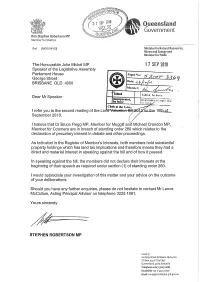

Dr Bruce Flegg MP

Queensland Government Hon Stephen Robertson MP Member for Stretton Ref [M0/10/4103] Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and Minister for Trade The Honourable John Mickel MP 17 SEP 2010 Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Parliament House George Street BRISBANE QLD 4000 Dear Mr Speaker Remainder incurpnrateii IN Icace.#. I refer you to the second reading of the. La September 2010. I believe that Dr Bruce Flegg MP, Member for Moggill and Michael Crandon MP, Member for Coomera are in breach of standing order 260 which relates to the declaration of pecuniary interest in debate and other proceedings. As indicated in the Register of Member's Interests, both members hold substantial property holdings which has land tax implications and therefore means they had a direct and material interest in speaking against the bill and of how it passed. In speaking against the bill, the members did not declare their interests at the beginning of their speech as required under section (1) of standing order 260. I would appreciate your investigation of this matter and your advice on the outcome of your deliberations. Should you have any further enquiries, please do not hesitate to contact Mr Lance McCallum, Acting Principal Advisor on telephone 3225 1861. Yours sincerely STEPHEN ROBERTSON MP Level 17 61 Mary Street Brisbane Qld 4000 PO Box 15216 City East Queensland 4002 Australia Telephone +617 3225 1861 Facsimilie +617 3225 1828 Email [email protected] HON JOHN MICKEL MP SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND 2 4 SEP 2010 Hon Stephen Robertson MP Minister for Natural Resources , Mines and Energy and Minister for Trade PO Box 15216 CITY EAST QLD 4002 Dear Minister I acknowledge your correspondence dated 17 September 2010, relating to Dr Bruce Flegg MP, Member for Moggill and Mr Michael Crandon MP, Member for Coomera speaking to the second reading of the Land Valuation Bill 2010 on 16 September 2010. -

Ap2 Final 16.2.17

PALASZCZUK’S SECOND YEAR AN OVERVIEW OF 2016 ANN SCOTT HOWARD GUILLE ROGER SCOTT with cartoons by SEAN LEAHY Foreword This publication1 is the fifth in a series of Queensland political chronicles published by the TJRyan Foundation since 2012. The first two focussed on Parliament.2 They were written after the Liberal National Party had won a landslide victory and the Australian Labor Party was left with a tiny minority, led by Annastacia Palaszczuk. The third, Queensland 2014: Political Battleground,3 published in January 2015, was completed shortly before the LNP lost office in January 2015. In it we used military metaphors and the language which typified the final year of the Newman Government. The fourth, Palaszczuk’s First Year: a Political Juggling Act,4 covered the first year of the ALP minority government. The book had a cartoon by Sean Leahy on its cover which used circus metaphors to portray 2015 as a year of political balancing acts. It focussed on a single year, starting with the accession to power of the Palaszczuk Government in mid-February 2015. Given the parochial focus of our books we draw on a limited range of sources. The TJRyan Foundation website provides a repository for online sources including our own Research Reports on a range of Queensland policy areas, and papers catalogued by policy topic, as well as Queensland political history.5 A number of these reports give the historical background to the current study, particularly the anthology of contributions The Newman Years: Rise, Decline and Fall.6 Electronic links have been provided to open online sources, notably the ABC News, Brisbane Times, The Guardian, and The Conversation. -

QUEENSLAND January to June 2001

552 Political Chronicles QUEENSLAND January to June 2001 JOHN WANNA and TRACEY ARKLAY School of Politics and Public Policy, Griffith University Playing Smart Politics with a Divided Opposition On 23 January, after embarking on a three week "listening tour" around the state's shopping centres, jumping on public transport and swimming with sharks, the Premier Peter Beattie called an early election for 17 February 2001 — with six months of his first term remaining. The campaign ran for 26 days, the shortest permissible under the Electoral Act. The catalyst for the snap poll was the damage to Beattie's government caused by the "electoral rorts" scandal involving mainly the powerful Australian Workers' Union faction. While the initial allegations of electoral fraud had involved pre-selection battles in two Townsville seats, the repercussions were much wider engulfing the entire party and bringing down the Deputy Premier Jim Elder and two backbenchers, Grant Musgrove and Mike Kaiser. However, Beattie's political opponents were divided and Labor benefitted from a four-way split among the conservative side of politics and some other conservative independents. From the outset of the campaign, Beattie attempted to present his team as "clean" and free of rorters. He argued that the evidence to the Shepherdson inquiry (see previous Queensland Political Chronicle) demonstrated that the rorters were "just a tiny cell of people acting alone, and they have resigned or been expelled, and I don't believe anyone else is involved" (Courier-Mail, 17 January 2001). As the campaign commenced, it became clear that Labor's campaign was not just organised around the Premier; Beattie was Labor's campaign.