The Neolithic of the Peak District: a Lefebvrian Social Geography Approach to Spatial Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyam | Derbyshire | S32 5QW

2 Fiddlers Mews Fiddlers Bridge | Main Road | Eyam | Derbyshire | S32 5QW 2 FIDDLERS MEWS.indd 1 01/07/2019 14:13 Seller Insight This welcoming family home sits within the beautiful, picturesque village of Eyam in the Peak District,” say the vendors of 2 Fiddlers Mews, “with excellent local cafes and pubs. Eyam is the perfect place for long summer walks through the countryside and is a highly desirable village to live in. The village has great public transport links, with a bus stop right outside the front door, that can get you to all the surrounding villages as well as Sheffield and Chesterfield, making this the perfect property for commuting to work.” Meanwhile, the 3 bedroom mews house lends itself to everyday family life and entertaining alike, with different spaces serving a variety of needs and occasions. “A lovely dining room, with views across the rolling countryside is perfect for entertaining guests and family,” say the vendors. “The dining area leads through double doors to the cosy living room which is perfect for an after dinner coffee. The courtyard provides ample parking for guests, so entertaining is always hassle free.” The outside space also has much to offer, making the most of summer sunshine and enjoying marvellous views. “The property has a gorgeous south facing garden that benefits from the warm afternoon sun,” say the vendors, “so is perfect for enjoying those long summer evenings. The garden also features a patio area with a sun awning to provide shade from the midday heat.” “With its spacious dining room making the most of spectacular countryside views, and a cosy living ideal for after dinner drinks, the property is just as suited to relaxed entertaining as it is to everyday family life.” “I will miss waking up to the beautiful views and being able to walk in the countryside practically outside of the front door. -

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009 Catherine Collins 2 Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire in 2008 and 2009 By Catherine Collins 2017 Access Cambridge Archaeology Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Cambridge Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QG 01223 761519 [email protected] http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/ (Front cover images: view south up Castle Street towards Peveril Castle, 2008 students on a trek up Mam Tor and test pit excavations at CAS/08/2 – copyright ACA & Mike Murray) 3 4 Contents 1 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 7 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 ACCESS CAMBRIDGE ARCHAEOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2 THE HIGHER EDUCATION FIELD ACADEMY ............................................................................................ 8 2.3 TEST PIT EXCAVATION AND RURAL SETTLEMENT STUDIES ...................................................................... 9 3 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND DESIRED OUTCOMES ........................................................................ 10 3.1 AIMS .......................................................................................................................................................... -

The JESSOP Consultancy Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford

The JESSOP Consultancy Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford Document no.: Ref: TJC2020.160 HERITAGE STATEMENT December 2020 NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Sir William Hill Road, Eyam, Derbyshire INTRODUCTION SCOPE DESIGNATIONS This document presents a heritage statement for the The building is not statutorily designated. buildings at the former Newfoundland Nursery, Sir There are a number of designated heritage assets William Hill Road, Grindleford, Derbyshire (Figure 1), between 500m and 1km of the site (Figure 1), National Grid Reference: SK 23215 78266. including Grindleford Conservation Area to the The assessment has been informed through a site south-east; a series of Scheduled cairns and stone visit, review of data from the Derbyshire Historic circles on Eyam Moor to the north-west, and a Environment Record and consultation of sources of collection of Grade II Listed Buildings at Cherry information listed in the bibliography. It has been Cottage to the north. undertaken in accordance with guidance published by The site lies within the Peak District National Park. Historic England, the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists and Peak District National Park Authority as set out in the Supporting Material section. The JESSOP Consultancy The JESSOP Consultancy The JESSOP Consultancy Cedar House Unit 18B, Cobbett Road The Old Tannery 38 Trap Lane Zone 1 Business Park Hensington Road Sheffield Burntwood Woodstock South Yorkshire Staffordshire Oxfordshire S11 7RD WS7 3GL OX20 1JL Tel: 0114 287 0323 Tel: 01543 479 226 Tel: 01865 364 543 NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Eyam, Derbyshire Heritage Statement - Report Ref: TJC2019.158 Figure 1: Site location plan showing heritage designations The JESSOP Consultancy 2 Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Eyam, Derbyshire Heritage Statement - Report Ref: TJC2019.158 SITE SUMMARY ARRANGEMENT The topography of the site falls steadily towards the east, with the buildings situated at around c.300m The site comprises a small group of buildings above Ordnance datum. -

Youlgrave's New Golf Society Tees

The Bugle A chance to blow your trumpet for the villagers of Alport, Middleton and Youlgrave No. 60 November 2003 Youlgrave’s new golf society tees off Although the George Hotel is best known for its darts and dominoes, the colourful village pub has become the unlikely base for Youlgrave’s budding golfers. The Conksbury Golf Society was established in May of this year, and at present has 12 members. Last month they enjoyed an outing to Shirland Golf Course, between Alfreton and Clay Cross, with Owen ’Taffy’ Jones emerging as the winner with 18 Stapleford points. He was presented with the prestigious egg cup trophy by the George Hotel’s Stephen Marsh (pictured right). Other members of the society Stephen Marsh (right) of the George Hotel presents who turned out for the October Owen ‘Taffy’ Jones with the egg cup trophy. round included Chris Cooke, Steve Hope, Adrian Murray, Gordon Coupe, John Montgomery and should contact Stephen Marsh at the Stephen Marsh. George Hotel (tel 636292). The Conksbury Golf Society welcomes For details of how the George’s darts new members – regardless of experience and domino teams are faring see ‘Pommie or ability – and anyone interested in joining Briefs’ on page 3. Published by the Bugle. Editor: Andrew McCloy, Greystones Cottage, Bankside, Youlgrave DE45 1WD, tel. 01629 636125, e-mail [email protected]. Contributions for the next issue to arrive by the 15th of the month. The views in this publication are not necessarily those of the editorial team. www.thebugle.org.uk. Printed by Greenaway Workshop, Hackney, Matlock (tel. -

The Origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 the Avebury Henge Is One of the Famous Mega

1 The origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2Mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 The Avebury henge is one of the famous mega- 7 lithic monuments of the European Neolithic, Research 8 yet much remains unknown about the detail 9 and chronology of its construction. Here, the 10 results of a new geophysical survey and 11 re-examination of earlier excavation records 12 illuminate the earliest beginnings of the 13 monument. The authors suggest that Ave- ’ 14 bury s Southern Inner Circle was constructed 15 to memorialise and monumentalise the site ‘ ’ 16 of a much earlier foundational house. The fi 17 signi cance here resides in the way that traces 18 of dwelling may take on special social and his- 19 torical value, leading to their marking and 20 commemoration through major acts of monu- 21 ment building. 22 23 Keywords: Britain, Avebury, Neolithic, megalithic, memory 24 25 26 Introduction 27 28 Alongside Stonehenge, the passage graves of the Boyne Valley and the Carnac alignments, the 29 Avebury henge is one of the pre-eminent megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic. ’ 30 Its 420m-diameter earthwork encloses the world s largest stone circle. This in turn encloses — — 31 two smaller yet still vast megalithic circles each approximately 100m in diameter and 32 complex internal stone settings (Figure 1). Avenues of paired standing stones lead from 33 two of its four entrances, together extending for approximately 3.5km and linking with 34 other monumental constructions. Avebury sits within the centre of a landscape rich in 35 later Neolithic monuments, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures 36 (Smith 1965; Pollard & Reynolds 2002; Gillings & Pollard 2004). -

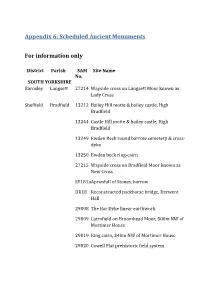

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

Rude Stone Monuments Chapt

RUDE STONE MONUMENTS IN ALL COUNTRIES; THEIR AGE AND USES. BY JAMES FERGUSSON, D. C. L., F. R. S, V.P.R.A.S., F.R.I.B.A., &c, WITH TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS. LONDON: ,JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1872. The right of Translation is reserved. PREFACE WHEN, in the year 1854, I was arranging the scheme for the ‘Handbook of Architecture,’ one chapter of about fifty pages was allotted to the Rude Stone Monuments then known. When, however, I came seriously to consult the authorities I had marked out, and to arrange my ideas preparatory to writing it, I found the whole subject in such a state of confusion and uncertainty as to be wholly unsuited for introduction into a work, the main object of which was to give a clear but succinct account of what was known and admitted with regard to the architectural styles of the world. Again, ten years afterwards, while engaged in re-writing this ‘Handbook’ as a History of Architecture,’ the same difficulties presented themselves. It is true that in the interval the Druids, with their Dracontia, had lost much of the hold they possessed on the mind of the public; but, to a great extent, they had been replaced by prehistoric myths, which, though free from their absurdity, were hardly less perplexing. The consequence was that then, as in the first instance, it would have been necessary to argue every point and defend every position. Nothing could be taken for granted, and no narrative was possible, the matter was, therefore, a second time allowed quietly to drop without being noticed. -

Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Simon John Kitcher MPhysGeog May 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where otherwise stated, and that it has not been previously submitted in application for any other degree at any other educational institution in the United Kingdom or overseas. ii Abstract Sub-fossil pollen from Holocene tufa pool sediments is used to investigate middle – late Holocene environmental conditions in the White Peak region of the Derbyshire Peak District in northern England. The overall aim is to use pollen analysis to resolve the relative influence of climate and anthropogenic landscape disturbance on the cessation of tufa production at Lathkill Dale and Monsal Dale in the White Peak region of the Peak District using past vegetation cover as a proxy. Modern White Peak pollen – vegetation relationships are examined to aid semi- quantitative interpretation of sub-fossil pollen assemblages. Moss-polsters and vegetation surveys incorporating novel methodologies are used to produce new Relative Pollen Productivity Estimates (RPPE) for 6 tree taxa, and new association indices for 16 herb taxa. RPPE’s of Alnus, Fraxinus and Pinus were similar to those produced at other European sites; Betula values displaying similarity with other UK sites only. RPPE’s for Fagus and Corylus were significantly lower than at other European sites. Pollen taphonomy in woodland floor mosses in Derbyshire and East Yorkshire is investigated. -

4. Vocabulary Cards Rectificado

n. someone who studies the past by recovering and examining remaining material evidence, such archaeologist as graves, buildings, tools, bones and pottery. “ The archaeologist excavated the site.” n. the study of past human life and culture by the recovery and examination of remaining evidence, such archaeology as graves, buildings, bones and pottery. n. someone who lives in a cave. “Prehistoric man found cave dweller shelter in caves. They became cave dwellers.” n. representations of wild, animals, painted on the walls of caves by prehistoric people, using cave painting simple tools such as fingers, twigs and leaves and using colours found in nature such as brown, red, black and green. adj. relating to the period in human culture before the bronze age, characterised by the chalcolithic use of copper and stone. “The bones were dug up at a chalcolithic site. There were bronze tools there, too.” adj. early form of modern human inhabiting Europe in the late paleolithic period (40,000 – 10,000 years cro-magnon ago). Skeletal remains were first found in the Cro- Magnon cave in southern France. “Homo Sapiens is a cro.magnon man.” n. structure usually regarded as a tomb, dolmen consisting of two or more large upright stones set with a space between and capped by a horizontal stone. n. place where archaeologists dig to find evidence of how excavation site humans lived in the past. “The excavation site is full of interesting things we can use to find out about the past.” n. very hard fine- grained quartz that spark when struck. Prehistoric people used flint this to make tools and start fire. -

Ume 10, -U Ser

Volume 10, -u ser . - 1968 Editors EDWARD S. DEEVEY a-- RICHARD FOSTER FLINT J. GORDON OGDEN, III _ IRVINg ROUSE Managing Editor RENEE S. KRA YALE UNIVERSITY NEW HAVEN, CONNECT.IC U l"ii)fl h d IiV r E AT\As g'LyyEi.. R C N, / r..? i.NA .3 8. ComIlient, usually corn ; fOg the date with other relevant dates, for each ,Ttdterial, silil"iiliari ing t e signitic.ance ant Sillpllilt 3't(i"r ing t., t t e radiocarbon t was i' itl ii73kinz 'P;.5 lit;re, i'; till teelmital :i"it.' i°_i , e.g. the iral lthout subscribers at $50.0( * Suggestions to authors of the reprints o the United Suites Geological Survey, 5th ed., Vashington, D. C., 1958 jc.=oscrxwxcn.t Panting ()ihce, $1.75). Volume 10, Number 1 - 1968 RADIOCARBON Published by THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE Editors EDWARD S. DEEVEY- RICHARD FOSTER FLINT J. GORDON OGDEN, III - IRVING ROUSE Managing Editor RENEE S. KRA YALE UNIVERSITY NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT VOL. 1 10, No. Radiocarbon 1965 CONTENTS Il1I Barker and John lackey British Museum Natural Radiocarbon Measurements V 1 BONN H. IV. Scharpenseel, F. Pietig, and M. A. Tawcrs Bonn Radiocarbon Measurements I ............................................... IRPA Anne Nicole Schreurs Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistirlue Radiocarbon Dates I ........ 9 Lu Soren Hkkansson University of Lund Radiocarbon Dates I Lv F. Gilot Louvain Natural Radiocarbon Measurements VI ..................... 55 1I H. R. Crane and J. B. Griffin University of Michigan. Radiocarbon Dates NII 61 N PL IV. J. Callow and G. I. Hassall National Physical Laboratory Radiocarbon Measurements V ..........