FLIGHT: Paleobiological and Present Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stable Structural Color Patterns Displayed on Transparent Insect Wings

Stable structural color patterns displayed on transparent insect wings Ekaterina Shevtsovaa,1, Christer Hanssona,b,1, Daniel H. Janzenc,1, and Jostein Kjærandsend,1 aDepartment of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 35, SE-22362 Lund, Sweden; bScientific Associate of the Entomology Department, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6018; and dDepartment of Biology, Museum of Zoology, Lund University, Helgonavägen 3, SE-22362 Lund, Sweden Contributed by Daniel H. Janzen, November 24, 2010 (sent for review October 5, 2010) Color patterns play central roles in the behavior of insects, and are and F). In laboratory conditions most wings are studied against a important traits for taxonomic studies. Here we report striking and white background (Fig. 1 G, H, and J), or the wings are embedded stable structural color patterns—wing interference patterns (WIPs) in a medium with a refractive index close to that of chitin (e.g., —in the transparent wings of small Hymenoptera and Diptera, ref. 19). In both cases the color reflections will be faint or in- patterns that have been largely overlooked by biologists. These ex- visible. tremely thin wings reflect vivid color patterns caused by thin film Insects are an exceedingly diverse and ancient group and interference. The visibility of these patterns is affected by the way their signal-receiver architecture of thin membranous wings the insects display their wings against various backgrounds with and color vision was apparently in place before their huge radia- different light properties. The specific color sequence displayed tion (20–22). The evolution of functional wings (Pterygota) that lacks pure red and matches the color vision of most insects, strongly can be freely operated in multidirections (Neoptera), coupled suggesting that the biological significance of WIPs lies in visual with small body size, has long been viewed as associated with their signaling. -

Consequences of Evolutionary Transitions in Changing Photic Environments

bs_bs_banner Austral Entomology (2017) 56,23–46 Review Consequences of evolutionary transitions in changing photic environments Simon M Tierney,1* Markus Friedrich,2,3 William F Humphreys,1,4,5 Therésa M Jones,6 Eric J Warrant7 and William T Wcislo8 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia. 2Department of Biological Sciences, Wayne State University, 5047 Gullen Mall, Detroit, MI 48202, USA. 3Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Wayne State University, School of Medicine, 540 East Canfield Avenue, Detroit, MI 48201, USA. 4Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, WA 6986, Australia. 5School of Animal Biology, University of Western Australia, Nedlands, WA 6907, Australia. 6Department of Zoology, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic. 3010, Australia. 7Department of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 35, S-22362 Lund, Sweden. 8Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, PO Box 0843-03092, Balboa, Ancón, Republic of Panamá. Abstract Light represents one of the most reliable environmental cues in the biological world. In this review we focus on the evolutionary consequences to changes in organismal photic environments, with a specific focus on the class Insecta. Particular emphasis is placed on transitional forms that can be used to track the evolution from (1) diurnal to nocturnal (dim-light) or (2) surface to subterranean (aphotic) environments, as well as (3) the ecological encroachment of anthropomorphic light on nocturnal habitats (artificial light at night). We explore the influence of the light environment in an integrated manner, highlighting the connections between phenotypic adaptations (behaviour, morphology, neurology and endocrinology), molecular genetics and their combined influence on organismal fitness. -

The Development of a Miniature Mechanism for Producing Insect Wing Motion

The development of a miniature mechanism for producing insect wing motion S. C. Burgess, K. Alemzadeh & L. Zhang Department of Mechanical Engineering, Bristol University, Bristol, UK Abstract Insects are capable of very agile flight on a small scale. If a man-made machine can be built that can fly like an insect, it would have important industrial, civil and military applications. Insects have complex wing motions including non- planar wing strokes and stroke reversal. This paper presents the design of a novel mechanism which can produce insect type wing motion. The mechanism is very light and compact and has potential for use in micro air vehicles. A prototype has been built and some preliminary tests have been carried out to characterize the mechanism performance. Keywords: insect flight, wing motion, novel mechanisms, wing reversal, lift. 1 Introduction The ability for controlled flight has existed in at least four classes of creature: (1) birds; (2) mammals (bats); (3) reptiles (pterosaurs); and (4) insects. Pterosaurs are believed to have been the largest fliers with wingspans up to 12m. It is thought that pterosaurs were capable of flapping flight because fossil records show a similar type of shoulder joint to that found in birds. Birds currently have a large range of size from the large albatross with a wingspan of up to 3.5m, to the tiny bumble hummingbird which has a span of only 8cm. Most birds can perform flapping flight but not true hovering flight. However, hummingbirds have a flexible shoulder joint which enables them to hover in windless conditions. Bats have a relatively small range of size. -

Quick Estimates of Flight Fitness in Hovering Animals, Including Novel Mechanisms for Lift Production

7. Exp. Biol. (1973). 59. 169-230 l6g With 23 text-figures Printed in Great Britain QUICK ESTIMATES OF FLIGHT FITNESS IN HOVERING ANIMALS, INCLUDING NOVEL MECHANISMS FOR LIFT PRODUCTION BY TORKEL WEIS-FOGH Department of Zoology, Cambridge CBz ^EJ, England (Received 11 January 1973) INTRODUCTION In a recent paper I have analysed the aerodynamics and energetics of hovering hummingbirds and DrosophUa and have found that, in spite of non-steady periods, the main flight performance of these types is consistent with steady-state aerodynamics (Weis-Fogh, 1972). The same may or may not apply to other flapping animals which practise hovering or slow forward flight at similar Reynolds numbers (Re), ioa to io*. As discussed in that paper, there are of course non-steady flow situations at the start and stop of each half-stroke of the wings. Moreover, it does not follow that all hovering animals make use mainly of steady-state principles. It is therefore desirable to obtain as simple and as easily analytical expressions as possible which should make it feasible to estimate the forces on the wings and the work and power produced. In this way one may make use of the large number of observations on freely flying animals to be found in the scattered literature. It may then be possible to identify the deviating groups and to approach the problems in a new way. This is the main purpose of the present studies, which both include new material and provide novel solutions. Major emphasis must be placed on simplicity. This involves approximations since the true flight system is so complicated as to be unmanageable. -

Exploring the Origin of Insect Wings from an Evo-Devo Perspective

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Exploring the origin of insect wings from an evo-devo perspective Courtney M Clark-Hachtel and Yoshinori Tomoyasu Although insect wings are often used as an example of once (i.e. are monophyletic) sometime during the Upper morphological novelty, the origin of insect wings remains a Devonian or Lower Carboniferous (370-330 MYA) [3,5,9]. mystery and is regarded as a major conundrum in biology. Over By the early Permian (300 MYA), winged insects had a century of debates and observations have culminated in two diversified into at least 10 orders [4]. Therefore, there is prominent hypotheses on the origin of insect wings: the tergal quite a large gap in the fossil record between apterygote hypothesis and the pleural hypothesis. However, despite and diverged pterygote lineages, which has resulted in a accumulating efforts to unveil the origin of insect wings, neither long-running debate over where insect wings have come hypothesis has been able to surpass the other. Recent from and how they have evolved. investigations using the evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) approach have started shedding new light on this Two proposed wing origins century-long debate. Here, we review these evo-devo studies The insect wing origin debate can be broken into two and discuss how their findings may support a dual origin of main groups of thought; wings evolved from the tergum of insect wings, which could unify the two major hypotheses. ancestral insects or wings evolved from pleuron-associat- Address ed structures (Figure 1. See Box 1 for insect anatomy) Miami University, Pearson Hall, 700E High Street, Oxford, OH 45056, [10 ]. -

The Role of Vortices in Animal Locomotion in Fluids

Applied and Computational Mechanics 8 (2014) 147–156 The role of vortices in animal locomotion in fluids R. Dvorˇak´ a,∗ a Institute of Thermomechanics v.v.i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Dolejˇskova 1402/5, 182 00 Prague, Czech Republic Received 26 March 2014; received in revised form 10 December 2014 Abstract The aim of this paper is to show the significance of vortices in animal locomotion in fluids on two deliberately chosen examples. The first example concerns lift generation by bird and insect wings, the second example briefly mentiones swimming and walking on water. In all the examples, the vortices generated by the moving animal impart the necessary momentum to the surrounding fluid, the reaction to which is the force moving or lifting the animal. c 2014 University of West Bohemia. All rights reserved. Keywords: animal locomotion, bird flight, flapping wings, insect flight, swimming, walking on water, vortices in animal propulsion 1. Introduction The topic is far too diverse to cover all aspects of animal locomotion both in (or on) water and air. All animals in water and air have inhabitated this planet for 300 million years (fishes and insects, twice as long as birds who are here about 150 million years), and they have had well enough time to develop their skill of swimming and flying. From the whole number of existing animal species almost 80 % have the capability of flying, out of which almost 99 % are insects (about 106 species). It is only less than half a century when people have begun to uncover the mechanism of their — often uncomprehensible — way of locomotion. -

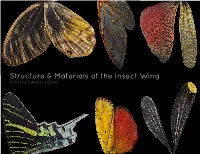

Structure & Materials of the Insect Wing

Structure & Materials of the Insect Wing Article by Samantha Chalut Background To this day, Evolution the true origins of insect flight remains obscure, as the earliest he earliest insects had four winged insects show evidence of Twings, independently being fully adept at flight. functioning forewings and hindwings. The well-known insects, n insect’s wings are outgrowths damselflies and dragonflies, have Aof the exoskeleton that enable kept this design. Since then, insect it to fly; this includes two pairs of wing designs vary where either the wings known as the forewing and forewing or hindwing are hindwing (although a select few specialized for force production, insects lack hindwings). The while many other insects are current designs of an insect wings functionally 2 winged through have evolved over hundreds of attaching the smaller hindwings millions of years to produce many to the forewings. variations, each with it’s own design tradeoffs. These tradeoffs may include specializations in the flight performance aspects such as efficiency, versatility, maneuverability, or stability. Structure he structure and design of an insect Twing is essential, as it must endure functionally over the insect’s lifespan. They must be capable of enduring collisions or tearing without failure. To achieve this insect wings can deform readily, even reversibly, through its overall structure. In many cases aerodynamic efficiency is improved through the coupling of the forewing and hindwing. This is achieved in a few different ways. Most commonly, the wings are coupled through a row of small hooks on the forward margin of the hindwing, locking onto the forewing. Another form of coupling is seen where Grasshopper forewing vein celled intersections the jugal lobe of the forewing covers a portion of the hindwing, or even where they broadly overlap. -

Phasmid Studies Volume 15 Issues 1&2

Printed ISSN 0966-0011 Online ISSN 1750-3329 PHASMID STUDIES Volume 15, numbers 1 & 2. March 2007. Editor: Dr. P.E. Bragg. Produced by the Phasmid Study Group The Phasmid Study Group. The Phasmid Study Group (PSG) was formed in 1980 to foster the study of phasmids. The group currently has several hundred members worldwide. The membership ranges from young children to professional entomologists. The PSG holds regular meetings and presents displays at all the major entomological exhibitions in the U.K. The PSG places emphasis on study by rearing and captive breeding and has a panel of breeders who distribute livestock to other members. The PSG produces two publications which are issued free to members. The Phasmid Study Group Newsletter is issued quarterly and contains news items, livestock information, details of exhibitions and meetings, and a variety of short articles on all aspects of phasmids. Phasmid Studies is issued on-line and in print. Typically it is produced biannually, in March and September, but this is currently under review. It contains longer articles on all aspects of phasmids, with an emphasis on natural history, captive breeding, taxonomy, and behavioural studies. Each issue contains abstracts of papers from other recent publications. Details of membership may be obtained from the Treasurer and Membership Secretary, Paul Brock, "Papillon", 40 Thorndike Road, Slough, Berks, SL2 1SR, U.K. Annual subscription rates are currently: U.K. £12.00; Europe £14.00; Worldwide £15.00. Phasma. This is a Dutch-Belgian group with similar aims to the Phasmid Study Group. It produces a quarterly newsletter, Phasma, which is published in Dutch. -

What Serial Homologs Can Tell Us About the Origin

F1000Research 2017, 6(F1000 Faculty Rev):268 Last updated: 17 JUL 2019 REVIEW What serial homologs can tell us about the origin of insect wings [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Yoshinori Tomoyasu 1*, Takahiro Ohde2,3*, Courtney Clark-Hachtel1* 1Department of Biology, Miami University, Pearson Hall, 700E High Street, Oxford, OH 45056, USA 2Division of Evolutionary Developmental Biology, National Institute for Basic Biology, 38 Nishigonaka Myodaiji, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan 3Department of Basic Biology, School of Life Science, SOKENDAI (The Graduate University for Advanced Studies), 38 Nishigonaka Myodaiji, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan * Equal contributors First published: 14 Mar 2017, 6(F1000 Faculty Rev):268 ( Open Peer Review v1 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10285.1) Latest published: 14 Mar 2017, 6(F1000 Faculty Rev):268 ( https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10285.1) Reviewer Status Abstract Invited Reviewers Although the insect wing is a textbook example of morphological novelty, 1 2 the origin of insect wings remains a mystery and is regarded as a chief conundrum in biology. Centuries of debates have culminated into two version 1 prominent hypotheses: the tergal origin hypothesis and the pleural origin published hypothesis. However, between these two hypotheses, there is little 14 Mar 2017 consensus in regard to the origin tissue of the wing as well as the evolutionary route from the origin tissue to the functional flight device. Recent evolutionary developmental (evo-devo) studies have shed new light F1000 Faculty Reviews are written by members of on the origin of insect wings. A key concept in these studies is “serial the prestigious F1000 Faculty. -

Size, Shape and Structure of Insect Wings

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/478768; this version posted November 26, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Size, shape and structure of insect wings Mary K. Salcedo,1, a) Jordan Hoffmann,2, a) Seth Donoughe,3 and L. Mahadevan1, 2, b) 1)Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 2)School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 3)Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL The size, shape and structure of insect wings are intimately linked to their ability to fly. However, there are few systematic studies of the variability of the natural patterns in wing morphology across insects. We assemble a comprehensive dataset of insect wings and analyze their morphology using topological and geometric notions in terms of i) wing size and contour shape, ii) vein geometry and topology, and iii) shape and distribution of wing membrane domains. These morphospaces are a first-step in defining the diversity of wing patterns across insect orders and set the stage for investigating their functional consequences. a)Equal contribution b)Electronic mail: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/478768; this version posted November 26, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. INTRODUCTION Of all the multicellular species on our planet, insects are the most speciose, with more than one million species1. -

Environmental and Biotic Controls on the Evolutionary History of Insect

Environmental and biotic controls on the evolutionary SEE COMMENTARY history of insect body size Matthew E. Clapham1 and Jered A. Karr Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Edited by James H. Brown, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, and approved April 27, 2012 (received for review March 7, 2012) Giant insects, with wingspans as large as 70 cm, ruled the Car- competitive or predatory interactions with flying vertebrates boniferous and Permian skies. Gigantism has been linked to (birds, bats, and pterosaurs), may have contributed to or even hyperoxic conditions because oxygen concentration is a key been the dominant control on evolutionary size trends (18, 19). physiological control on body size, particularly in groups like The rich fossil history of insects (21) contains the only record of flying insects that have high metabolic oxygen demands. Here evolutionary body-size trends in response to changing atmospheric we show, using a dataset of more than 10,500 fossil insect wing pO2 (22), temperature, and evolution of flying predators and lengths, that size tracked atmospheric oxygen concentrations only competitors (23). Our quantitative analysis of evolutionary size for the first 150 Myr of insect evolution. The data are best ex- trends from more than 10,500 measured fossil insect specimens plained by a model relating maximum size to atmospheric en- confirms the importance of atmospheric pO2 in enabling the evo- vironmental oxygen concentration (pO2) until the end of the lution of large body size, but suggests that the pO2-size relationship Jurassic, and then at constant sizes, independent of oxygen fluc- was superseded by biological factors following the evolution and tuations, during the Cretaceous and, at a smaller size, the Ceno- aerial specialization of flying vertebrates, particularly birds. -

Animal Abstracts 44

ABSTRACT BOOK SEB BRIGHTON 2016 4–7 July, 2016 BRIGHTON CENTRE,UK SEBIOLOGY.ORG #SEBAMM SUN, SEA & SCIENCE SOCIETY FOR EXPERIMENTAL BIOLOGY ABSTRACTS ANIMAL BIOLOGY 2 ANNUAL MAIN MEETING BRIGHTON 2016 ANIMAL ABSTRACTS 44 A1 DEVELOPMENTAL BIOMECHANICS OF MOTOR SKILLS ORGANISED BY:PROF JOHAN VAN LEEUWEN (WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY, NETHERLANDS) & PROF PETER AERTS (UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP, BELGIUM) i n loca l be nd i ng powe r a s t he fi sh g rows. We developed a combi ned A1.1 ACQUIRED VERSUS INNATE experimental and computational approach for reconstructing time- PREY CAPTURING SKILLS IN SUPER- resolved bending moment distributions from high-speed videos of f ree -sw i m m i ng la r vae (2-12 dpf ). Fi rst, we recon st r uc t t he t h ree - PRECOCIAL LIVE-BEARING FISH dimensional position, orientation and body curvature from these i mages. We feed t hese recon st r uc t ion s i nto a computat iona l flu id- TUESDAY 5 JULY, 2016 13:45 dynamics solver in order to calculate the flow field and the fluid forces a long t he fi sh’s body. Fi na l ly, we combi ne t he mot ion of t he long it ud i na l body a x i s a nd t he e x te r na l flu id forces a s i nput for a n MARTIN LANKHEET (WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY, NETHERLANDS) opt i m i zat ion procedu re to ca lc u late t he best fit t i ng t i me - depe nde nt Live-bearing fish start hunting for mobile prey within hours after bending moment distribution.