Chapter 11- Dinosaurs and the Hierarchy of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stable Structural Color Patterns Displayed on Transparent Insect Wings

Stable structural color patterns displayed on transparent insect wings Ekaterina Shevtsovaa,1, Christer Hanssona,b,1, Daniel H. Janzenc,1, and Jostein Kjærandsend,1 aDepartment of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 35, SE-22362 Lund, Sweden; bScientific Associate of the Entomology Department, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6018; and dDepartment of Biology, Museum of Zoology, Lund University, Helgonavägen 3, SE-22362 Lund, Sweden Contributed by Daniel H. Janzen, November 24, 2010 (sent for review October 5, 2010) Color patterns play central roles in the behavior of insects, and are and F). In laboratory conditions most wings are studied against a important traits for taxonomic studies. Here we report striking and white background (Fig. 1 G, H, and J), or the wings are embedded stable structural color patterns—wing interference patterns (WIPs) in a medium with a refractive index close to that of chitin (e.g., —in the transparent wings of small Hymenoptera and Diptera, ref. 19). In both cases the color reflections will be faint or in- patterns that have been largely overlooked by biologists. These ex- visible. tremely thin wings reflect vivid color patterns caused by thin film Insects are an exceedingly diverse and ancient group and interference. The visibility of these patterns is affected by the way their signal-receiver architecture of thin membranous wings the insects display their wings against various backgrounds with and color vision was apparently in place before their huge radia- different light properties. The specific color sequence displayed tion (20–22). The evolution of functional wings (Pterygota) that lacks pure red and matches the color vision of most insects, strongly can be freely operated in multidirections (Neoptera), coupled suggesting that the biological significance of WIPs lies in visual with small body size, has long been viewed as associated with their signaling. -

Chapter 10, the Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W

Chapter 10, The Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W. H. Freeman, 1998. CHAPTER 10 Dinosaurs Challenge Evolution Enter Sir Richard Owen More than 150 years ago, the great British naturalist Richard Owen (fig. 10.01) ignited the controversy that Deinonychus would eventually inflame. The word "dinosaur" was first uttered by Owen in a lecture delivered at Plymouth, England in July of 1841. He had coined the name in a report on giant fossil reptiles that were discovered in England earlier in the century. The root, Deinos, is usually translated as "terrible" but in his report, published in 1842, Owen chose the words "fearfully great"1. To Owen, dinosaurs were the fearfully great saurian reptiles, known only from fossil skeletons of huge extinct animals, unlike anything alive today. Fig. 10.01 Richard Owen as, A) a young man at about the time he named Dinosauria, B) in middle age, near the time he described Archaeopteryx, and C) in old age. Dinosaur bones were discovered long before Owen first spoke their name, but no one understood what they represented. The first scientific report on a dinosaur bone belonging was printed in 1677 by Rev. Robert Plot in his work, The Natural History of Oxfordshire. This broken end of a thigh bone, came to Plot's attention during his research. It was nearly 60 cm in circumference--greater than the same bone in an elephant (fig.10.02). We now suspect that it belonged to Megalosaurus bucklandii, a carnivorous dinosaur now known from Oxfordshire. But Plot concluded that it "must have been a real Bone, now petrified" and that it resembled "exactly the figure of the 1 Chapter 10, The Mistaken Extinction, by Lowell Dingus and Timothy Rowe, New York, W. -

New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 24, 2021 New perspectives on pterosaur palaeobiology DAVID W. E. HONE1*, MARK P. WITTON2 & DAVID M. MARTILL2 1Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E14NS, UK 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Burnaby Road, Portsmouth PO1 3QL, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight and occupied the skies of the Mesozoic for 160 million years. They occurred on every continent, evolved their incredible pro- portions and anatomy into well over 100 species, and included the largest flying animals of all time among their ranks. Pterosaurs are undergoing a long-running scientific renaissance that has seen elevated interest from a new generation of palaeontologists, contributions from scientists working all over the world and major advances in our understanding of their palaeobiology. They have espe- cially benefited from the application of new investigative techniques applied to historical speci- mens and the discovery of new material, including detailed insights into their fragile skeletons and their soft tissue anatomy. Many aspects of pterosaur science remain controversial, mainly due to the investigative challenges presented by their fragmentary, fragile fossils and notoriously patchy fossil record. With perseverance, these controversies are being resolved and our understand- ing of flying reptiles is increasing. This volume brings together a diverse set of papers on numerous aspects of the biology of these fascinating reptiles, including discussions of pterosaur ecology, flight, ontogeny, bony and soft tissue anatomy, distribution and evolution, as well as revisions of their taxonomy and relationships. -

Consequences of Evolutionary Transitions in Changing Photic Environments

bs_bs_banner Austral Entomology (2017) 56,23–46 Review Consequences of evolutionary transitions in changing photic environments Simon M Tierney,1* Markus Friedrich,2,3 William F Humphreys,1,4,5 Therésa M Jones,6 Eric J Warrant7 and William T Wcislo8 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia. 2Department of Biological Sciences, Wayne State University, 5047 Gullen Mall, Detroit, MI 48202, USA. 3Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Wayne State University, School of Medicine, 540 East Canfield Avenue, Detroit, MI 48201, USA. 4Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, WA 6986, Australia. 5School of Animal Biology, University of Western Australia, Nedlands, WA 6907, Australia. 6Department of Zoology, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic. 3010, Australia. 7Department of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 35, S-22362 Lund, Sweden. 8Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, PO Box 0843-03092, Balboa, Ancón, Republic of Panamá. Abstract Light represents one of the most reliable environmental cues in the biological world. In this review we focus on the evolutionary consequences to changes in organismal photic environments, with a specific focus on the class Insecta. Particular emphasis is placed on transitional forms that can be used to track the evolution from (1) diurnal to nocturnal (dim-light) or (2) surface to subterranean (aphotic) environments, as well as (3) the ecological encroachment of anthropomorphic light on nocturnal habitats (artificial light at night). We explore the influence of the light environment in an integrated manner, highlighting the connections between phenotypic adaptations (behaviour, morphology, neurology and endocrinology), molecular genetics and their combined influence on organismal fitness. -

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves I. Background Scientists have speculated about evolution of birds ever since Darwin. Difficult to find relatives using only modern animals After publi cati on of “O rigi i in of S peci es” (~1860) some used birds as a counter-argument since th ere were no k nown t ransiti onal f orms at the time! • turtles have modified necks and toothless beaks • bats fly and are warm blooded With fossil discovery other potential relationships! • Birds as distinct order of reptiles Many non-reptilian characteristics (e.g. endothermy, feathers) but really reptilian in structure! If birds only known from fossil record then simply be a distinct order of reptiles. II. Reptile Evolutionary History A. “Stem reptiles” - Cotylosauria Must begin in the late Paleozoic ClCotylosauri a – “il”“stem reptiles” Radiation of reptiles from Cotylosauria can be organized on the basis of temporal fenestrae (openings in back of skull for muscle attachment). Subsequent reptilian lineages developed more powerful jaws. B. Anapsid Cotylosauria and Chelonia have anapsid pattern C. Syypnapsid – single fenestra Includes order Therapsida which gave rise to mammalia D. Diapsida – both supppratemporal and infratemporal fenestrae PttPattern foun did in exti titnct arch osaurs, survi iiving archosaurs and also in primitive lepidosaur – ShSpheno don. All remaining living reptiles and the lineage leading to Aves are classified as Diapsida Handout Mammalia Extinct Groups Cynodontia Therapsida Pelycosaurs Lepidosauromorpha Ichthyosauria Protorothyrididae Synapsida Anapsida Archosauromorpha Euryapsida Mesosaurs Amphibia Sauria Diapsida Eureptilia Sauropsida Amniota Tetrapoda III. Relationshippp to Reptiles Most groups present during Mesozoic considere d ancestors to bird s. -

The Development of a Miniature Mechanism for Producing Insect Wing Motion

The development of a miniature mechanism for producing insect wing motion S. C. Burgess, K. Alemzadeh & L. Zhang Department of Mechanical Engineering, Bristol University, Bristol, UK Abstract Insects are capable of very agile flight on a small scale. If a man-made machine can be built that can fly like an insect, it would have important industrial, civil and military applications. Insects have complex wing motions including non- planar wing strokes and stroke reversal. This paper presents the design of a novel mechanism which can produce insect type wing motion. The mechanism is very light and compact and has potential for use in micro air vehicles. A prototype has been built and some preliminary tests have been carried out to characterize the mechanism performance. Keywords: insect flight, wing motion, novel mechanisms, wing reversal, lift. 1 Introduction The ability for controlled flight has existed in at least four classes of creature: (1) birds; (2) mammals (bats); (3) reptiles (pterosaurs); and (4) insects. Pterosaurs are believed to have been the largest fliers with wingspans up to 12m. It is thought that pterosaurs were capable of flapping flight because fossil records show a similar type of shoulder joint to that found in birds. Birds currently have a large range of size from the large albatross with a wingspan of up to 3.5m, to the tiny bumble hummingbird which has a span of only 8cm. Most birds can perform flapping flight but not true hovering flight. However, hummingbirds have a flexible shoulder joint which enables them to hover in windless conditions. Bats have a relatively small range of size. -

How to Find a Dinosaur, and the Role of Synonymy in Biodiversity Studies

Paleobiology, 34(4), 2008, pp. 516–533 How to find a dinosaur, and the role of synonymy in biodiversity studies Michael J. Benton Abstract.—Taxon discovery underlies many studies in evolutionary biology, including biodiversity and conservation biology. Synonymy has been recognized as an issue, and as many as 30–60% of named species later turn out to be invalid as a result of synonymy or other errors in taxonomic practice. This error level cannot be ignored, because users of taxon lists do not know whether their data sets are clean or riddled with erroneous taxa. A year-by-year study of a large clade, Dinosauria, comprising over 1000 taxa, reveals how systematists have worked. The group has been subject to heavy review and revision over the decades, and the error rate is about 40% at generic level and 50% at species level. The naming of new species and genera of dinosaurs is proportional to the number of people at work in the field. But the number of valid new dinosaurian taxa depends mainly on the discovery of new territory, particularly new sedimentary basins, as well as the number of paleontologists. Error rates are highest (Ͼ50%) for dinosaurs from Europe; less well studied con- tinents show lower totals of taxa, exponential discovery curves, and lower synonymy rates. The most prolific author of new dinosaur names was Othniel Marsh, who named 80 species, closely followed by Friedrich von Huene (71) and Edward Cope (64), but the ‘‘success rate’’ (proportion of dinosaurs named that are still regarded as valid) was low (0.14–0.29) for these earlier authors, and it appears to improve through time, partly a reflection of reduction in revision time, but mainly because modern workers base their new taxa on more complete specimens. -

Quick Estimates of Flight Fitness in Hovering Animals, Including Novel Mechanisms for Lift Production

7. Exp. Biol. (1973). 59. 169-230 l6g With 23 text-figures Printed in Great Britain QUICK ESTIMATES OF FLIGHT FITNESS IN HOVERING ANIMALS, INCLUDING NOVEL MECHANISMS FOR LIFT PRODUCTION BY TORKEL WEIS-FOGH Department of Zoology, Cambridge CBz ^EJ, England (Received 11 January 1973) INTRODUCTION In a recent paper I have analysed the aerodynamics and energetics of hovering hummingbirds and DrosophUa and have found that, in spite of non-steady periods, the main flight performance of these types is consistent with steady-state aerodynamics (Weis-Fogh, 1972). The same may or may not apply to other flapping animals which practise hovering or slow forward flight at similar Reynolds numbers (Re), ioa to io*. As discussed in that paper, there are of course non-steady flow situations at the start and stop of each half-stroke of the wings. Moreover, it does not follow that all hovering animals make use mainly of steady-state principles. It is therefore desirable to obtain as simple and as easily analytical expressions as possible which should make it feasible to estimate the forces on the wings and the work and power produced. In this way one may make use of the large number of observations on freely flying animals to be found in the scattered literature. It may then be possible to identify the deviating groups and to approach the problems in a new way. This is the main purpose of the present studies, which both include new material and provide novel solutions. Major emphasis must be placed on simplicity. This involves approximations since the true flight system is so complicated as to be unmanageable. -

University of Birmingham Work on the Victorian Dinosaur

University of Birmingham Work on the Victorian Dinosaur Tattersdill, William DOI: 10.1111/lic3.12394 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Tattersdill, W 2017, 'Work on the Victorian Dinosaur: Histories and Prehistories of Nineteenth-Century Palaeontology', Literature Compass, vol. 14, no. 6, e12394. https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12394 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Tattersdill W. Work on the Victorian dinosaur: Histories and prehistories of 19th- century palaeontology. Literature Compass. 2017;14, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12394. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Exploring the Origin of Insect Wings from an Evo-Devo Perspective

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Exploring the origin of insect wings from an evo-devo perspective Courtney M Clark-Hachtel and Yoshinori Tomoyasu Although insect wings are often used as an example of once (i.e. are monophyletic) sometime during the Upper morphological novelty, the origin of insect wings remains a Devonian or Lower Carboniferous (370-330 MYA) [3,5,9]. mystery and is regarded as a major conundrum in biology. Over By the early Permian (300 MYA), winged insects had a century of debates and observations have culminated in two diversified into at least 10 orders [4]. Therefore, there is prominent hypotheses on the origin of insect wings: the tergal quite a large gap in the fossil record between apterygote hypothesis and the pleural hypothesis. However, despite and diverged pterygote lineages, which has resulted in a accumulating efforts to unveil the origin of insect wings, neither long-running debate over where insect wings have come hypothesis has been able to surpass the other. Recent from and how they have evolved. investigations using the evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) approach have started shedding new light on this Two proposed wing origins century-long debate. Here, we review these evo-devo studies The insect wing origin debate can be broken into two and discuss how their findings may support a dual origin of main groups of thought; wings evolved from the tergum of insect wings, which could unify the two major hypotheses. ancestral insects or wings evolved from pleuron-associat- Address ed structures (Figure 1. See Box 1 for insect anatomy) Miami University, Pearson Hall, 700E High Street, Oxford, OH 45056, [10 ]. -

The Role of Vortices in Animal Locomotion in Fluids

Applied and Computational Mechanics 8 (2014) 147–156 The role of vortices in animal locomotion in fluids R. Dvorˇak´ a,∗ a Institute of Thermomechanics v.v.i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Dolejˇskova 1402/5, 182 00 Prague, Czech Republic Received 26 March 2014; received in revised form 10 December 2014 Abstract The aim of this paper is to show the significance of vortices in animal locomotion in fluids on two deliberately chosen examples. The first example concerns lift generation by bird and insect wings, the second example briefly mentiones swimming and walking on water. In all the examples, the vortices generated by the moving animal impart the necessary momentum to the surrounding fluid, the reaction to which is the force moving or lifting the animal. c 2014 University of West Bohemia. All rights reserved. Keywords: animal locomotion, bird flight, flapping wings, insect flight, swimming, walking on water, vortices in animal propulsion 1. Introduction The topic is far too diverse to cover all aspects of animal locomotion both in (or on) water and air. All animals in water and air have inhabitated this planet for 300 million years (fishes and insects, twice as long as birds who are here about 150 million years), and they have had well enough time to develop their skill of swimming and flying. From the whole number of existing animal species almost 80 % have the capability of flying, out of which almost 99 % are insects (about 106 species). It is only less than half a century when people have begun to uncover the mechanism of their — often uncomprehensible — way of locomotion. -

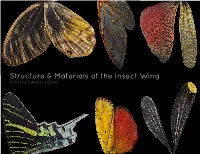

Structure & Materials of the Insect Wing

Structure & Materials of the Insect Wing Article by Samantha Chalut Background To this day, Evolution the true origins of insect flight remains obscure, as the earliest he earliest insects had four winged insects show evidence of Twings, independently being fully adept at flight. functioning forewings and hindwings. The well-known insects, n insect’s wings are outgrowths damselflies and dragonflies, have Aof the exoskeleton that enable kept this design. Since then, insect it to fly; this includes two pairs of wing designs vary where either the wings known as the forewing and forewing or hindwing are hindwing (although a select few specialized for force production, insects lack hindwings). The while many other insects are current designs of an insect wings functionally 2 winged through have evolved over hundreds of attaching the smaller hindwings millions of years to produce many to the forewings. variations, each with it’s own design tradeoffs. These tradeoffs may include specializations in the flight performance aspects such as efficiency, versatility, maneuverability, or stability. Structure he structure and design of an insect Twing is essential, as it must endure functionally over the insect’s lifespan. They must be capable of enduring collisions or tearing without failure. To achieve this insect wings can deform readily, even reversibly, through its overall structure. In many cases aerodynamic efficiency is improved through the coupling of the forewing and hindwing. This is achieved in a few different ways. Most commonly, the wings are coupled through a row of small hooks on the forward margin of the hindwing, locking onto the forewing. Another form of coupling is seen where Grasshopper forewing vein celled intersections the jugal lobe of the forewing covers a portion of the hindwing, or even where they broadly overlap.