A Systemic Analysis of the Apologetic Rhetoric of Hurricane Katrina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ext Generatio

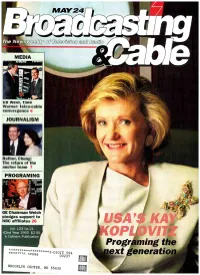

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

To Download April 21-May 5

[email protected] • April 21-May 5, 2021 • mulletwrapper.com • 850-492-5221 Local playwright Laura Pfizenmayer’s autobiographical cancer survivor dramedy opens April 30 at SBCT Local playwright Laura Pfizenmayer (front) and the cast from the South Baldwin Community Theater production of “Cancer Can Kiss My A$$” run a rehearsal for the plays world premier at SBCT on April 30 at 7:30 p.m. The dramedy chronicles the journey of Jean’s battle and triumph over anal cancer and is based on Laura’s own story. Its six runs also include 7:30 shows on May 1, 7 & 8 and 2:30 p.m. matinees on May 2 and 9. For tickets and more info, visit sbct.biz for tickets and more information. “During lockdown I wrote a dramadey recounting my own cancer journey and now South Baldwin is giving it a world premiere,’’ Laura said. “The theatre is thrilled to be welcoming back our patrons while still observing all COVID guidelines.’’ Directed by Jan Hinnen, the cast includes Ann Gaynor, Mel Middlebrooks, Barbara Campbell, Steve Henry, Rio Cordy and Robert Gardner. (Photo by Dan Mennuto) Page 2 • The Mullet Wrapper • April 21-May 5, 2021 • Ad. Info: 850-492-5221 • SHARE YOUR COMMUNITY NEWS• E-Mail: [email protected] A Bill McGinnes owned local institution for 36 years ZZA OUSY PI EER & L WARM B HOME OF THE WHO’S YOUR DADDY BURGER LIVE MUSIC NIGHTLY HAPPY HOUR 11-7 NEVER A COVER MON, TUE, WED & THURS MON-FRI Smokey Otis & Mark Laborde MAY 7-8 & 21-22 Bo Grant FULL MENU (formerly of The Platters) MAY 1: Tim Roberts ‘TIL MIDNIGHT MAY 14: Tim Robinson MAY 29: Delta Donnie Ad. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

2006-2007 Impact Report

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2006–2007 Annual Report From the IWMF Executive Director and Co-Chairs March 2008 Dear Friends and Supporters, As a global network the IWMF supports women journalists throughout the world by honoring their courage, cultivating their leadership skills, and joining with them to pioneer change in the news media. Our global commitment is reflected in the activities documented in this annual report. In 2006-2007 we celebrated the bravery of Courage in Journalism honorees from China, the United States, Lebanon and Mexico. We sponsored an Iraqi journalist on a fellowship that placed her in newsrooms with American counterparts in Boston and New York City. In the summer we convened journalists and top media managers from 14 African countries in Johannesburg to examine best practices for increasing and improving reporting on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. On the other side of the world in Chicago we simultaneously operated our annual Leadership Institute for Women Journalists, training mid-career journlists in skills needed to advance in the newsroom. These initiatives were carried out in the belief that strong participation by women in the news media is a crucial part of creating and maintaining freedom of the press. Because our mission is as relevant as ever, we also prepared for the future. We welcomed a cohort of new international members to the IWMF’s governing board. We geared up for the launch of leadership training for women journalists from former Soviet republics. And we added a major new journalism training inititiative on agriculture and women in Africa to our agenda. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections by Jennifer M

GOVERNORS The National Mood and the Seats in Play: Understanding the 2016 Gubernatorial Elections By Jennifer M. Jensen and Thad Beyle With a national anti-establishment mood and 12 gubernatorial elections—eight in states with a Democrat as sitting governor—the Republicans were optimistic that they would strengthen their hand as they headed into the November elections. Republicans already held 31 governor- ships to the Democrats’ 18—Alaska Gov. Bill Walker is an Independent—and with about half the gubernatorial elections considered competitive, Republicans had the potential to increase their control to 36 governors’ mansions. For their part, Democrats had a realistic chance to convert only a couple of Republican governorships to their party. Given the party’s win-loss potential, Republicans were optimistic, in a good position. The Safe Races North Dakota Races in Delaware, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah Republican incumbent Jack Dalrymple announced and Washington were widely considered safe for he would not run for another term as governor, the incumbent party. opening the seat up for a competitive Republican primary. North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Delaware Stenehjem received his party’s endorsement at Popular Democratic incumbent Jack Markell was the Republican Party convention, but multimil- term-limited after fulfilling his second term in office. lionaire Doug Burgum challenged Stenehjem in Former Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, the primary despite losing the party endorsement. eldest son of former Vice President Joe Biden, was Lifelong North Dakota resident Burgum had once considered a shoo-in to succeed Markell before founded a software company, Great Plains Soft- a 2014 recurrence of brain cancer led him to stay ware, that was eventually purchased by Microsoft out of the race. -

Advertising Opportunity Guide Print

AAAE’S AAAE DELIVERS FOR AIRPORT EXECUTIVES NO.1 RATED PRODUCT M AG A Z IN E AAAEAAAE DELIVERSDELIVERS FOR AIRPORTAIRPORT EXECUTIVESEXECUTIVES AAAE DELIVERS FOR AIRPORT EXECUTIVES AAAE DELIVERS FOR AIRPORT EXECUTIVES MMAGAZINE AG A Z IN E MAGAZINE MAGAZINE www.airportmagazine.net | August/September 2015 www.airportmagazine.net | June/July 2015 www.airportmagazine.net | February/March 2015 NEW TECHNOLOGY AIDS AIRPORTS, PASSENGERS NON-AERONAUTICAL REVENUE SECURITYU.S. AIRPORT TRENDS Airport Employee n Beacons Deliver Airport/ Screening Retail Trends Passenger Benefits n Hosting Special Events UAS Security Issues Editorial Board Outlook for 2015 n CEO Interview Airport Diversity Initiatives Risk-Based Security Initiatives ADVERTISING OPPORTUNITY GUIDE PRINT ONLINE DIGITAL MOBILE AIRPORT MAGAZINE AIRPORT MAGAZINE ANDROID APP APPLE APP 2016 | 2016 EDITORIAL MISSION s Airport Magazine enters its 27th year of publication, TO OUR we are proud to state that we continue to produce AVIATION Atop quality articles that fulfill the far-ranging needs of airports, including training information; the lessons airports INDUSTRY have learned on subjects such as ARFF, technology, airfield and FRIENDS terminal improvements; information about the state of the nation’s economy and its impact on air service; news on regulatory and legislative issues; and much more. Further, our magazine continues to make important strides to bring its readers practical and timely information in new ways. In addition to printed copies that are mailed to AAAE members and subscribers, we offer a full digital edition, as well as a free mobile app that can be enjoyed on Apple, Android and Kindle Fire devices. In our app you will discover the same caliber of content you’ve grown to expect, plus mobile-optimized text, embedded rich media, and social media connectivity. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

SEPTEMBER 2018 The

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce SEPTEMBER 2018 the A Decade of Team Mobile Travels to Farnborough to Promote Mobile Economic Chamber Names Two to Development Economic Development Team Progress the business view SEPTEMBER 2018 1 business Your business comes first. That’s why we’re #1 in reliability. So we deliver industry leading levels of reliability, ensuring you get the performance and uptime your business needs from a solution you rely on every day. HD HD Voice Quality Premium Polycom Phones Best in class uptime and reliability Unlimited Nationwide Calling Cloud-based PBX We manage your phone service so you can focus on whatever drives your results. C Spire. Customer inspired. 2cspire.com/business the business view SEPTEMBER 2018 | [email protected] | 251.459.8999 ©2018 C Spire. All rights reserved. the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce SEPTEMBER 2018 | In this issue business 4 News You Can Use ON THE COVER 21 23 20 22 24 25 9 Small Business of the Month: About the cover: Since 2007, 16 17 15 18 19 McFadden Engineering Inc. there have literally been dozens 11 12 13 14 of economic announcements 11 Investor Focus: Warren Averett LLC by local operations expanding 6 7 8 9 10 12 Team Mobile Works Aerospace Show and companies moving into Your business comes first. 4 the area. We invited CEOs and 15 CEO Profile: Jim Nagy, Mobile Arts 1 5 senior staff to join us for our and Sports Association/Reese’s 3 cover photo. They represent 2 Senior Bowl companies investing in the That’s why we’re #1 in reliability. -

Famous Journalist Research Project

Famous Journalist Research Project Name:____________________________ The Assignment: You will research a famous journalist and present to the class your findings. You will introduce the journalist, describe his/her major accomplishments, why he/she is famous, how he/she got his/her start in journalism, pertinent personal information, and be able answer any questions from the journalism class. You should make yourself an "expert" on this person. You should know more about the person than you actually present. You will need to gather your information from a wide variety of sources: Internet, TV, magazines, newspapers, etc. You must include a list of all sources you consult. For modern day journalists, you MUST read/watch something they have done. (ie. If you were presenting on Barbara Walters, then you must actually watch at least one interview/story she has done, or a portion of one, if an entire story isn't available. If you choose a writer, then you must read at least ONE article written by that person.) Source Ideas: Biography.com, ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, CNN or any news websites. NO WIKIPEDIA! The Presentation: You may be as creative as you wish to be. You may use note cards or you may memorize your presentation. You must have at least ONE visual!! Any visual must include information as well as be creative. Some possibilities include dressing as the character (if they have a distinctive way of dressing) & performing in first person (imitating the journalist), creating a video, PowerPoint or make a poster of the journalist’s life, a photo album, a smore, or something else! The main idea: Be creative as well as informative. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

Miss Minden to Pass on Crown Saturday

CRIME TRACKER Arrests made in Webster Parish PAGE 3 MINDEN RESS ERALD P -H www.press-herald.com December 4, 2015 | 50 Cents FRIDAY INSIDE today BurglaryMINDEN CRIME suspect arrested Accused of stealing Apaches, Lady Tiders get money out of car big wins MICHELLE BATES [email protected] SPORTS PG.8 Minden police arrested a Sarepta man after he was reported to have stolen cash from a vehicle. Cameron Alfred, 18, of the 300 block of Harper Street in Sarepta, was charged with simple burglary Tuesday. Minden Police Chief Steve Crop- per says the inci- dent occurred around 3 a.m., when a man appeared to be ALFRED White MISS MINDEN TO PASS sleeping in the dri- ver’s seat of a vehicle at an apart- chocolate ment complex on Lewisville Road. “The victim indicated that he cherry pie and his wife were coming out of ON CROWN SATURDAY the apartment complex getting LIFE PG.5 ready to go to work,” he said, “and SeeARREST, Page 2 iss Minden 2015 Baylee Howell tried to sum up her year in one word and came up short; however, she says every girl needs to experi- ence Miss Minden and Miss Louisiana. AT THE CAPITOL M “My year as Miss Minden was absolutely incredible,” she said. “I’m really saddened that INSIDE Edwards MEET THE 2016 MISS it’s coming to an end now, and it hasn’t been anything MINDEN PAGEANT short of amazing. I have grown so much as a person, and CONTESTANTS, PAGE 7. I’ve gotten to experience so much.