Freedom on the Net 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018

Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited Company Telecommunication Pakistan PTCL PAKISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2018 REPORT ANNUAL /ptcl.official /ptclofficial ANNUAL REPORT Pakistan Telecommunication /theptclcompany Company Limited www.ptcl.com.pk PTCL Headquarters, G-8/4, Islamabad, Pakistan Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Contents 01COMPANY REVIEW 03FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CONSOLIDATED Corporate Vision, Mission & Core Values 04 Auditors’ Report to the Members 129-135 Board of Directors 06-07 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 136-137 Corporate Information 08 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss 138 The Management 10-11 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 139 Operating & Financial Highlights 12-16 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 140 Chairman’s Review 18-19 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 141 Group CEO’s Message 20-23 Notes to and Forming Part of the Consolidated Financial Statements 142-213 Directors’ Report 26-45 47-46 ہ 2018 Composition of Board’s Sub-Committees 48 Attendance of PTCL Board Members 49 Statement of Compliance with CCG 50-52 Auditors’ Review Report to the Members 53-54 NIC Peshawar 55-58 02STATEMENTS FINANCIAL Auditors’ Report to the Members 61-67 Statement of Financial Position 68-69 04ANNEXES Statement of Profit or Loss 70 Pattern of Shareholding 217-222 Statement of Comprehensive Income 71 Notice of 24th Annual General Meeting 223-226 Statement of Cash Flows 72 Form of Proxy 227 Statement of Changes in Equity 73 229 Notes to and Forming Part of the Financial Statements 74-125 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Vision Mission To be the leading and most To be the partner of choice for our admired Telecom and ICT provider customers, to develop our people in and for Pakistan. -

The Protean Nature of the Fifth Republic Institutions (Duverger)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Ben Clift Article Title: The Fifth Republic at Fifty: The Changing Face of French Politics and Political Economy Year of publication: 2008 Link to published article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09639480802413322 Publisher statement: This is an electronic version of an article published in Clift, B. (2008). The Fifth Republic at Fifty: The Changing Face of French Politics and Political Economy. Modern & Contemporary France, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 383-.398. Modern & Contemporary France is available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/cmcf20/16/4 Modern and Contemporary France Special Issue - Introduction Dr. Ben Clift Senior Lecturer in Political Economy, Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK Email: [email protected] web: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/staff/clift/ The Fifth Republic at Fifty: The Changing Face of French Politics and Political Economy. At its inception, a time of great political upheaval in France, it was uncertain whether the new regime would last five years, let alone fifty. The longevity of the regime is due in part to its flexibility and adaptability, which is a theme explored both below and in all of the contributions to this special issue. -

New Branches for the 2Africa Subsea Cable System

New branches for the 2Africa subsea cable system 16 August, 2021: The 2Africa consortium, comprised of China Mobile International, Facebook, MTN GlobalConnect, Orange, stc, Telecom Egypt, Vodafone and WIOCC, announced today the addition of four new branches to the 2Africa cable. The branches will extend 2Africa’s connectivity to the Seychelles, the Comoros Islands, and Angola, and bring a new landing to south-east Nigeria. The new branches join the recently announced extension to the Canary Islands. 2Africa, which will be the largest subsea cable project in the world, will deliver faster, more reliable internet service to each country where it lands. Communities that rely on the internet for services from education to healthcare, and business will experience the economic and social benefits that come from this increased connectivity. Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN) has been selected to deploy the new branches, which will increase the number of 2Africa landings to 35 in 26 countries, further improving connectivity into and around Africa. As with other 2Africa cable landings, capacity will be available to service providers at carrier- neutral data centres or open-access cable landing stations on a fair and equitable basis, encouraging and supporting the development of a healthy internet ecosystem. Marine surveys completed for most of the cable and Cable manufacturing is underway Since launching the 2Africa cable in May 2020, the 2Africa consortium has made considerable progress in planning and preparing for the deployment of the cable, which is expected to ‘go live’ late 2023. Most of the subsea route survey activity is now complete. ASN has started manufacturing the cable and building repeater units in its factories in Calais and Greenwich to deploy the first segments in 2022. -

Final Communique

ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF COMMUNAUTE ECONOMIQUE WEST AFRICAN STATES DES ETATS DE L'AFRIQUE ^ DE L'OUEST WENTY SIXTH SESSION OF THE AUTHORITY OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT Dakar, 31 January 2003 Final Communique • J/v^ u'\ Final Communique of the 26m Session of the Authority Page 1 1. The twenty sixth ordinary session of the Authority of Heads of State and Government of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), washeid in Dakar on 31 January 2003. underthe Chairmanship of His Excellency Maitre Abdoulave Wade, President of the Republic of Senegal, and current Chairman of ECOWAS. 2. The following Heads of State and Government or their duly accredited representatives were present at the session: His Excellency Mathieu Kerekou President of the Republic of Benin His Excellency John Agyekum Kufuor President of the Republic of Ghana His Excellency Koumba Yaila President of the Republic of Guinea Bissau His Excellency Charles Gankay Iayior President of the Republic of Liberia His Excellency Amadou Toumani Toure President of the Republic of Mali His Excellency Mamadou Tandja President of the Republic of Niger His Excellency Olusegun Obasanic President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria His Excellency Abdoulaye Wade President of the Republic of Senegal His Excellency General Gnassingbe Eyadem; President of the Togolese Republic Y-\er Excellency, isatou Njie-Saidy Vice-President of the Republic a The Gambia Representing the President of the Republic His Excellency Ernest Paramanga Yonli Prime Minister . \ Representing the President of Faso \ Final Communique ofthe 26m Session of the Authority Paae 2 His Excellency Lamine Sidime Prime Minister of the Republic of Guinea Representing the President of the Republic Mrs Fatima Veiga Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation Representing the President of Cabo Verde Mr. -

Political System of France the Fifth Republic • the Fifth Republic Was

Political System of France The Fifth Republic • The fifth republic was established in 1958, and was largely the work of General de Gaulle - its first president, and Michel Debré his prime minister. It has been amended 17 times. Though the French constitution is parliamentary, it gives relatively extensive powers to the executive (President and Ministers) compared to other western democracies. • A popular referendum approved the constitution of the French Fifth Republic in 1958, greatly strengthening the authority of the presidency and the executive with respect to Parliament. • The constitution does not contain a bill of rights in itself, but its preamble mentions that France should follow the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, as well as those of the preamble to the constitution of the Fourth Republic. • This has been judged to imply that the principles laid forth in those texts have constitutional value, and that legislation infringing on those principles should be found unconstitutional if a recourse is filed before the Constitutional Council. The executive branch • The head of state and head of the executive is the President, elected by universal suffrage. • France has a semi-presidential system of government, with both a President and a Prime Minister. • The Prime Minister is responsible to the French Parliament. • A presidential candidate is required to obtain a nationwide majority of non- blank votes at either the first or second round of balloting, which implies that the President is somewhat supported by at least half of the voting population. • The President of France, as head of state and head of the executive, thus carries more power than leaders of most other European countries, where the two functions are separate (for example in the UK, the Monarch and the Prime minister, in Germany the President and the Chancellor.) • Since May 2017, France's president is Emmanuel Macron, who was elected to the post at age 39, the youngest French leader since Napoleon. -

Egypt: Freedom on the Net 2017

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2017 Egypt 2016 2017 Population: 95.7 million Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2016 (ITU): 39.2 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 15 16 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 15 18 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 33 34 TOTAL* (0-100) 63 68 Press Freedom 2017 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2016 – May 2017 • More than 100 websites—including those of prominent news outlets and human rights organizations—were blocked by June 2017, with the figure rising to 434 by October (se Blocking and Filtering). • Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services are restricted on most mobile connections, while repeated shutdowns of cell phone service affected residents of northern Sinai (Se Restrictions on Connectivity). • Parliament is reviewing a problematic cybercrime bill that could undermine internet freedom, and lawmakers separately proposed forcing social media users to register with the government and pay a monthly fee (see Legal Environment and Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • Mohamed Ramadan, a human rights lawyer, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and a 5-year ban on using the internet, in retaliation for his political speech online (see Prosecutions and Detentions for Online Activities). • Activists at seven human rights organizations on trial for receiving foreign funds were targeted in a massive spearphishing campaign by hackers seeking incriminating information about them (see Technical Attacks). 1 www.freedomonthenet.org Introduction FREEDOM EGYPT ON THE NET Obstacles to Access 2017 Introduction Availability and Ease of Access Internet freedom declined dramatically in 2017 after the government blocked dozens of critical news Restrictions on Connectivity sites and cracked down on encryption and circumvention tools. -

Egypt Presidential Election Observation Report

EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT JULY 2014 This publication was produced by Democracy International, Inc., for the United States Agency for International Development through Cooperative Agreement No. 3263-A- 13-00002. Photographs in this report were taken by DI while conducting the mission. Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: +1.301.961.1660 www.democracyinternational.com EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT July 2014 Disclaimer This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Democracy International, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................ 4 MAP OF EGYPT .......................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................. II DELEGATION MEMBERS ......................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................... X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 6 ABOUT DI .......................................................... 6 ABOUT THE MISSION ....................................... 7 METHODOLOGY .............................................. 8 BACKGROUND ........................................................ 10 TUMULT -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

In May 2011, Freedom House Issued a Press Release Announcing the Findings of a Survey Recording the State of Media Freedom Worldwide

Media in North Africa: the Case of Egypt 10 Lourdes Pullicino In May 2011, Freedom House issued a press release announcing the findings of a survey recording the state of media freedom worldwide. It reported that the number of people worldwide with access to free and independent media had declined to its lowest level in over a decade.1 The survey recorded a substantial deterioration in the Middle East and North Africa region. In this region, Egypt suffered the greatest set-back, slipping into the Not Free category in 2010 as a result of a severe crackdown preceding the November 2010 parliamentary elections. In Tunisia, traditional media were also censored and tightly controlled by government while internet restriction increased extensively in 2009 and 2010 as Tunisians sought to use it as an alternative field for public debate.2 Furthermore Libya was included in the report as one of the world’s worst ten countries where independent media are considered either non-existent or barely able to operate and where dissent is crushed through imprisonment, torture and other forms of repression.3 The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Arab Knowledge Report published in 2009 corroborates these findings and view the prospects of a dynamic, free space for freedom of thought and expression in Arab states as particularly dismal. 1 Freedom House, (2011): World Freedom Report, Press Release dated May 2, 2011. The report assessed 196 countries and territories during 2010 and found that only one in six people live in countries with a press that is designated Free. The Freedom of the Press index assesses the degree of print, broadcast and internet freedom in every country, analyzing the events and developments of each calendar year. -

1 During the Opening Months of 2011, the World Witnessed a Series Of

FREEDOM HOUSE Freedom on the Net 2012 1 EGYPT 2011 2012 Partly Partly POPULATION: 82 million INTERNET FREEDOM STATUS Free Free INTERNET PENETRATION 2011: 36 percent Obstacles to Access (0-25) 12 14 WEB 2.0 APPLICATIONS BLOCKED: Yes NOTABLE POLITICAL CENSORSHIP: No Limits on Content (0-35) 14 12 BLOGGERS/ ICT USERS ARRESTED: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 28 33 PRESS FREEDOM STATUS: Partly Free Total (0-100) 54 59 * 0=most free, 100=least free NTRODUCTION I During the opening months of 2011, the world witnessed a series of demonstrations that soon toppled Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year presidency. The Egyptian revolution received widespread media coverage during the Arab Spring not only because of Egypt’s position as a main political hub in the Middle East and North Africa, but also because activists were using different forms of media to communicate the events of the movement to the world. While the Egyptian government employed numerous tactics to suppress the uprising’s roots online—including by shutting down internet connectivity, cutting off mobile communications, imprisoning dissenters, blocking media websites, confiscating newspapers, and disrupting satellite signals in a desperate measure to limit media coverage—online dissidents were able to evade government pressure and spread their cause through social- networking websites. This led many to label the Egyptian revolution the Facebook or Twitter Revolution. Since the introduction of the internet in 1993, the Egyptian government has invested in internet infrastructure as part of its strategy to boost the economy and create job opportunities. The Telecommunication Act was passed in 2003 to liberalize the private sector while keeping government supervision and control over information and communication technologies (ICTs) in place. -

Pdf 8 Methodology Development, Ranking Digital Rights

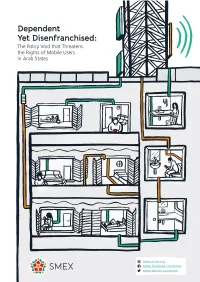

SMEX is a Beirut-based media development and digital rights organization working to advance self-regulating information societies. Our mission is to defend digital rights, promote open culture and local content, and encourage critical engagement with digital technologies, media, and networks through research, knowledge-sharing, and advocacy. Design, illustration concept, and layout are by Salam Shokor, with assistance from David Badawi. Illustrations are by Ahmad Mazloum and Salam Shokor. www.smex.org A 2018 Publication of SMEX Kmeir Building, 4th Floor, Badaro, Beirut, Lebanon © Social Media Exchange Association, 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Acknowledgments Afef Abrougui conceptualized this research report and designed and oversaw execution of the methodology for data collection and review. Research was conducted between April and July 2017. Talar Demirdjian and Nour Chaoui conducted data collection. Jessica Dheere edited the report, with proofreading assistance from Grant Baker. All errors and omissions are strictly the responsibility of SMEX. This study would not have been possible without the guidance and feedback of Rebecca Mackinnon, Nathalie Maréchal, and the whole team at Ranking Digital Rights (www.rankingdigitalrights.org). RDR works with an international community of researchers to set global standards for how internet, mobile, and telecommunications companies should respect freedom of expression and privacy. The 2017 Corporate Accountability Index ranked 22 of the world’s most powerful such companies on their disclosed commitments and policies that affect users' freedom of expression and privacy. The methodology developed for this research study was based on the RDR/ CAI methodology. We are also grateful to EFF’s Katitza Rodriguez and Access Now’s Peter Micek, both of whom shared valuable insights and expertise into how our research might be transformed and contextualized for local campaigns. -

Facebook Revolution": Exploring the Meme-Like Spread of Narratives During the Egyptian Protests

It was a "Facebook revolution": Exploring the meme-like spread of narratives during the Egyptian protests. Fue una "Revolución de Facebook": Explorando la narrativa de los meme difundidos durante las protestas egipcias. Summer Harlow1 Recibido el 14 de mayo de 2013- Aceptado el 22 de julio de 2013 ABSTRACT: Considering online social media’s importance in the Arab Spring, this study is a preliminary exploration of the spread of narratives via new media technologies. Via a textual analysis of Facebook comments and traditional news media stories during the 2011 Egyptian uprisings, this study uses the concept of “memes” to move beyond dominant social movement paradigms and suggest that the telling and re-telling, both online and offline, of the principal narrative of a “Facebook revolution” helped involve people in the protests. Keywords: Activism, digital media, Egypt, social media, social movements. RESUMEN: Éste es un estudio preliminar sobre el rol desempeñado por un estilo narrativo de los medios sociales, conocido como meme, durante la primavera árabe. Para ello, realiza un análisis textual de los principales comentarios e historias vertidas en Facebook y retratadas en los medios tradicionales, durante las protestas egipcias de 2011. En concreto, este trabajo captura los principales “memes” de esta historia, en calidad de literatura principal de este movimiento social y analiza cómo el contar y el volver a contar estas historias, tanto en línea como fuera de línea, se convirtió en un estilo narrativo de la “revolución de Facebook” que ayudó a involucrar a la gente en la protesta. Palabras claves: Activismo, medios digitales, Egipto, medios sociales, movimientos sociales.