Pdf 8 Methodology Development, Ranking Digital Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018

Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited Company Telecommunication Pakistan PTCL PAKISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2018 REPORT ANNUAL /ptcl.official /ptclofficial ANNUAL REPORT Pakistan Telecommunication /theptclcompany Company Limited www.ptcl.com.pk PTCL Headquarters, G-8/4, Islamabad, Pakistan Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Contents 01COMPANY REVIEW 03FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CONSOLIDATED Corporate Vision, Mission & Core Values 04 Auditors’ Report to the Members 129-135 Board of Directors 06-07 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 136-137 Corporate Information 08 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss 138 The Management 10-11 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 139 Operating & Financial Highlights 12-16 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 140 Chairman’s Review 18-19 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 141 Group CEO’s Message 20-23 Notes to and Forming Part of the Consolidated Financial Statements 142-213 Directors’ Report 26-45 47-46 ہ 2018 Composition of Board’s Sub-Committees 48 Attendance of PTCL Board Members 49 Statement of Compliance with CCG 50-52 Auditors’ Review Report to the Members 53-54 NIC Peshawar 55-58 02STATEMENTS FINANCIAL Auditors’ Report to the Members 61-67 Statement of Financial Position 68-69 04ANNEXES Statement of Profit or Loss 70 Pattern of Shareholding 217-222 Statement of Comprehensive Income 71 Notice of 24th Annual General Meeting 223-226 Statement of Cash Flows 72 Form of Proxy 227 Statement of Changes in Equity 73 229 Notes to and Forming Part of the Financial Statements 74-125 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Vision Mission To be the leading and most To be the partner of choice for our admired Telecom and ICT provider customers, to develop our people in and for Pakistan. -

Liste Des Nouvelles Destinations Roaming Au Cameroun

POSTPAID Country Operator Outbound 1 New-Zealand Vodafone New-Zealand Live 2 Albania Vodafone Albania Live 3 Algerie Optimum Telecom Algeria Spa Live 4 Algerie Wataniya Télécom Algérie Live 5 Angola Unitel S.A. Live 6 Armenia MTS Armenia CJSC Live 7 Armenia UCOM LLC Live 8 Armenia VEON Armenia CJSC/ArmenTel Live 9 Australia Vodafone Hutchison Australia Pty Limited Live 10 Australia SingTel Optus Pty Limited Live 11 Australia Vodafone Hutchison Australia Pty Limited Live 12 Austria A1 Telekom Austria AG Live 13 Austria Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH Live 14 Azerbaijan Azerfon LLC Live 15 Azerbaijan Bakcell Limited Liable Company Live 16 Bahrain Zain Bahrain B.S.C Live 17 Bangladesh Grameenphone Ltd Live 18 Belgium Telenet Group BVBA/SPRL Live 19 Belgium ORANGE Belgium nv/SA Live 20 Belgium Proximus PLC Live 21 Benin Etisalat Benin SA Live 22 Benin Spacetel-Benin Live 23 Botswana Orange Botswana (Pty) Ltd Live 24 Brazil Claro S.A Live 25 Brazil TIM Celular S.A. Live 26 Brazil TIM Celular S.A. Live 27 Brazil TIM Celular S.A. Live 28 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria EAD Live 29 Burkina Faso Orange Burkina Faso S.A Live 30 Burkina Faso Onatel Live 31 Burkina Faso Telecel Faso S.A. Live 32 Burundi Africell PLC Company Live 33 Burundi Econetleo Live 34 Burundi Africell Live 35 Burundi Lacell SU Live 36 Cambodge metfone/Viettel Live 37 Cambodia Smart Axiata Co., Ltd. Live 38 Canada Rogers Communications Canada Inc. Live 39 Canada Rogers Communications Canada Inc. Live 40 Canada Bell Mobility Inc. Live 41 Canada TELUS Communications Inc. -

Orange Corporate Social Responsibility 2014 Review

ORANGE CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 2014 REVIEW Within its approach on corporate social responsibility, Orange has set precise objectives for several years. Here is the review of the 20014 achievements 1 Corporate Social Responsibility / 2014 review / Orange Contents APPROACH ................................................................................................................ 3 ETHICS................................................................................................................................. 3 COMBATING CORRUPTION ...................................................................................................... 3 STAKEHOLDER DIALOGUE ....................................................................................................... 3 Dialogue in countries ......................................................................................................................... 3 Group level dialogue .......................................................................................................................... 4 Dialogue applied to specific issues or services .................................................................................. 4 Digital Society Forum ......................................................................................................................... 5 A TRUSTED SUPPORT FOR ALL THROUGHOUT THE DIGITAL WORLD .................... 6 OUR CUSTOMERS ................................................................................................................. -

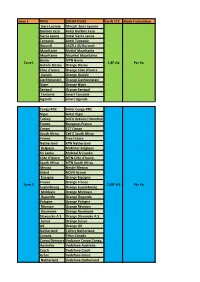

Zone 1 PAYS OPERATEURS Tarifs TTC Mode Facturation Siera

Zone 1 PAYS OPERATEURS Tarifs TTC Mode Facturation Siera Leonne Africell Siera Leonne Burkina Faso Airtel Burkina Faso Sierra Leone Airtel Sierra Leone Tanzanie Airtel Tanzanie Burundi LACELL SU Burundi Mauritanie Mattel Mauritania Mauritanie Mauritel Mauritanie Benin MTN Benin Zone1 1,8F cfa Par Ko Guinée Bissau Orange Bissau Côte d'Ivoire Orange Côte d'Ivoire Guinée Orange Guinée Liechteinstein Orange Liechteinstein Niger Orange Niger Senegal Orange Senegal Tanzanie Smart Tanzanie Uganda Smart Uganda Congo RDC Airtel Congo RDC Niger Airtel Niger Turkey AVEA Iletisim Hizmetleri A.S. (Aycell) Turkey France Bouygues France Congo CCT Congo South Africa Cell C South Africa France Free France Netherland KPN Netherland Belgique Mobistar Belgique Sri Lanka Mobitel Sri Lanka Côte d'Ivoire MTN Côte d'Ivoire South Africa MTN South Africa Mexico Nextel Mexico Island NOVA IsLand Espagne Orange Espagne France Orange France Zone 2 2,95F cfa Par Ko Luxembourg Orange Luxembourg Moldavie Orange Moldavie Ouganda Orange Ouganda Pologne Orange Pologne Réunion Orange Réunion Roumanie Orange Roumanie Slovensko A.S. Orange Slovensko A.S. Suisse Orange Suisse UK Orange UK Netherland Telfort Netherland Canada Telus Canada Congo DemocraticVodacom Congo Congo, Democratic Republic of the Australia Vodafone Australia Czech Vodafone Czech Grèce Vodafone Grèce Netherland Vodafone Netherland Belgique Base Belgique Belgacom Belgacom Benin Moov Benin Canada Rogiers Canada Canada Microcel Canada Swiss Com Swiss Com Côte d'Ivoire Moov Côte d'Ivoire Cap Vert Cap Vert Mobile -

2017 Registration Document

2017 Registration document Annual financial report Table of contents 1. Overview of the Group 5. Corporate, social and and of its business environmental responsibility 1.1 Overview 4 5.1 Social commitments 311 1.2 Market and strategy 7 5.2 Employee information 316 1.3 Operating activities 12 5.3 Environmental information 328 1.4 Networks and real- estate 38 5.4 Duty of care 337 1.5 Innovation at Orange 40 5.5 Report by one of the Statutory Auditors 338 1.6 Regulation of telecom activities 43 6. Shareholder Base 2. Risk factors and activity and Shareholders’ Meeting management framework 6.1 Share capital 342 2.1 Risk factors 64 6.2 Major shareholders 343 2.2 Activity and risk management framework 69 6.3 Draft resolutions to be submitted to the Combined Ordinary and Extraordinary Shareholders’ Meeting of May 4, 2018 345 3. Financial report 6.4 Report of the Board of Directors on the resolutions submitted to the Combined Ordinary and 3.1 Analysis of the Group’s financial position and earnings 78 Extraordinary Shareholders’ Meeting of May 4, 2018 350 3.2 Recent events and Outlook 131 6.5 Statutory Auditors’ report on resolutions 3.3 Consolidated financial statements 133 and related party agreements 357 3.4 Annual financial statements Orange SA 240 3.5 Dividend distribution policy 278 7. Additional information 4. Corporate Governance 7.1 Person responsible 362 7.2 Statutory Auditors 362 4.1 Composition of management and supervisory bodies 280 7.3 Statutory information 363 4.2 Functioning of the management 7.4 Factors that may have an impact in the event and supervisory bodies 290 of a public offer 365 4.3 Reference to a Code of Corporate Governance 298 7.5 Regulated agreements and related party transactions 366 4.4 Compensation and benefits paid to Directors, 7.6 Material contracts 366 Officers and Senior Management 298 8. -

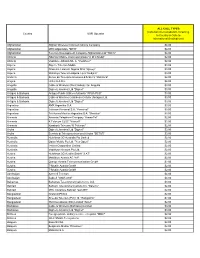

New Simplification Rates

NEW VOICE RATES AS OF JULY 14, 2009 Country GSM Operator All Voice calls: Back to Canada/US, Incoming Calls, In Country Calls, Calls to International Destinations Afghanistan MTN Afganistan, "MTN" $4.00 Afghanistan Afghan Wireless Communications Company $4.00 Afghanistan Telecom Development Company Afghanistan Ltd "TDCA" $4.00 Albania Albanian Mobile Communications "A M C Mobil" $2.00 Albania Vodafone Albania Sh. A. "Vodafone" $2.00 Algeria Algerie Telecom Mobile $3.00 Algeria Orascom Telecom Algeria SPA "Djezzy" $3.00 Algeria Wataniya Telecom Algerie s.p.a."Nedjma" $3.00 Andorra Servei de Telecomunicacions d'Andorra "Mobiland" $2.00 Angola Unitel S.A.R.L. $4.00 Anguilla Cable & Wireless (West Indies) Ltd. Anguilla $3.00 Anguilla Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Antigua Public Utilities Authority "APUA PCS" $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Cable & Wireless Caribbean Cellular (Antigua) Ltd. $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Argentina AMX Argentina S.A. $3.00 Argentina Telefonica Moviles Argentina S.A. "Movistar" $3.00 Argentina Telecom Personal S.A. "Personal" $3.00 Armenia Armenia Telephone Company "ArmenTel" $2.00 Armenia K Telecom CJSC "Vivacell" $2.00 Armenia Karaback Telecom "K Telecom" $2.00 Aruba Servicio di Telecomunicacion di Aruba "SETAR" $3.00 Aruba Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Australia Hutchison 3G Australia Pty Limited $2.00 Australia Optus Mobile Pty Ltd. "Yes Optus" $2.00 Australia Telstra Corporation Limited $2.00 Australia Vodafone Network Pty Ltd. $2.00 Austria Orange Austria Telecommunication GmbH $2.00 Austria Hutchison 3G Austria GmbH "3 AT" $2.00 Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH $2.00 Austria Mobilkom Austria AG "A1" $2.00 Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH $2.00 Azerbaijan Azercell Telecom $4.00 Azerbaijan Bakcell "GSM 2000" $4.00 Bahamas Bahamas Telecommunications Co. -

New Simplification Rates

ALL CALL TYPES (Calls back to Canada/US, Incoming, Country GSM Operator In Country & Calls to International Destinations) Afghanistan Afghan Wireless Communications Company $4.00 Afghanistan MTN Afganistan, "MTN" $4.00 Afghanistan Telecom Development Company Afghanistan Ltd "TDCA" $4.00 Albania Albanian Mobile Communications "A M C Mobil" $2.00 Albania Vodafone Albania Sh. A. "Vodafone" $2.00 Algeria Algerie Telecom Mobile $3.00 Algeria Orascom Telecom Algeria SPA "Djezzy" $3.00 Algeria Wataniya Telecom Algerie s.p.a."Nedjma" $3.00 Andorra Servei de Telecomunicacions d'Andorra "Mobiland" $2.00 Angola Unitel S.A.R.L. $4.00 Anguilla Cable & Wireless (West Indies) Ltd. Anguilla $3.00 Anguilla Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Antigua Public Utilities Authority "APUA PCS" $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Cable & Wireless Caribbean Cellular (Antigua) Ltd. $3.00 Antigua & Barbuda Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Argentina AMX Argentina S.A. $3.00 Argentina Telecom Personal S.A. "Personal" $3.00 Argentina Telefonica Moviles Argentina S.A. "Movistar" $3.00 Armenia Armenia Telephone Company "ArmenTel" $2.00 Armenia K Telecom CJSC "Vivacell" $2.00 Armenia Karaback Telecom "K Telecom" $2.00 Aruba Digicel (Jamaica) Ltd "Digicel" $3.00 Aruba Servicio di Telecomunicacion di Aruba "SETAR" $3.00 Australia Hutchison 3G Australia Pty Limited $2.00 Australia Optus Mobile Pty Ltd. "Yes Optus" $2.00 Australia Telstra Corporation Limited $2.00 Australia Vodafone Network Pty Ltd. $2.00 Austria Hutchison 3G Austria GmbH "3 AT" $2.00 Austria Mobilkom Austria AG "A1" $2.00 Austria Orange Austria Telecommunication GmbH $2.00 Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH $2.00 Austria T-Mobile Austria GmbH $2.00 Azerbaijan Azercell Telecom $4.00 Azerbaijan Bakcell "GSM 2000" $4.00 Bahamas Bahamas Telecommunications Co. -

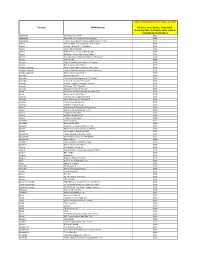

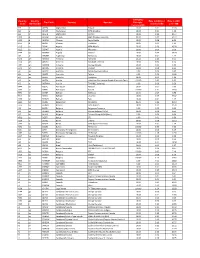

Country Code Country ISO Number Tap Code Country Operator

Charging Country Country Rate in USD per Rate in USD Tap Code Country Operator Principle Code ISO Number increment kb per 1 MB increment kb +93 af AFGEA Afghanistan Etisalat 10.00 0.11 11.18 +93 af AFGAR Afghanistan MTN (Areeba) 10.00 0.01 1.30 +93 af AFGTD Afghanistan Roshan 10.00 0.10 10.27 +355 al ALBAM Albania AMC (Telekom Albania) 50.00 0.49 10.13 +355 al ALBEM Albania Eagle Mobile 10.00 0.08 8.02 +355 al ALBVF Albania Vodafone 10.00 0.01 1.13 +213 dz DZAA1 Algeria ATM-Mobilis 20.00 0.20 10.28 +213 dz DZAWT Algeria Wataniya 10.00 0.00 0.30 +244 ao AGOMV Angola Movicel 10.00 0.14 13.99 +54 ar ARGTM Argentina Telefonica 10.00 0.01 1.42 +374 am ARM01 Armenia Armentel 10.24 0.10 9.65 +374 am ARMKT Armenia Karabakh Telecom 10.00 0.08 8.24 +374 am ARMOR Armenia Orange (Ucom) 10.00 0.01 1.09 +374 am ARM05 Armenia VivaCell 10.00 0.08 8.24 +61 au AUSOP Australia Optus Communications 1.00 0.00 0.33 +61 au AUSTA Australia Telstra 1.00 0.02 21.02 +61 au AUSVF Australia Vodafone 10.00 0.01 1.10 +43 at AUTCA Austria Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH (Connect- One/ Orange) 100.00 0.83 8.53 +43 at AUTMM Austria T MOBILE (telering) 1.00 0.00 0.58 +994 az AZEAC Azerbaijan Azercell 10.00 0.07 7.00 +994 az AZEBC Azerbaijan Bakcell 100.00 1.71 17.50 +973 bh BHRBT Bahrain BATELCO 10.00 0.07 6.98 +973 bh BHRST Bahrain Viva STC 10.00 0.19 19.02 +973 bh BHRMV Bahrain Zain 10.00 0.01 1.17 +880 bd BGDBL Bangladesh Banglalink 50.00 0.49 10.10 +375 by BLRMD Belarus MDC Velcom 10.00 0.12 12.78 +32 be BELTB Belgium Belgacom-Proximus 1.00 0.00 0.62 +32 be BELMO Belgium -

Annual Report 2017 Financial Highlights

To access the digital version, please visit our Annual Report microsite at: http://mobily.im/annualreport-en Rising to the Challenge Annual Report 2017 Financial Highlights Operational Cash Flow (EBITDA–CAPEX) Deleveraging (Net Debt and Net Debt / EBITDA) (SAR million) (SAR million) +60.8% -9.3% 2,000 14,000 13,993 12,687 12,000 12,527 1,378 10,000 1,000 857 8,000 6,000 3.5x 3.5x 0 4.26x 4,000 (543) 2,000 -1,000 0 2015* 2016 2017 2015* 2016 2017 Net Debt Net Debt/EBITDA This year was an important turning point for Mobily, in which the Revenues EBITDA and EBITDA Margin Company developed and articulated a new corporate strategy for growth (SAR million) (SAR million) to 2019 and beyond. -9.7% -10.4% 15,000 5,000 14,424 4,000 12,569 4,069 10,000 11,351 3,000 3,646 32% 2,941 2,000 32% 5,000 1,000 20% 0 0 2015* 2016 2017 2015* 2016 2017 EBITDA EBITDA Margin Net Income/(Loss) (SAR million) 0 -200 (214) -400 -600 (709) -800 -1,000 (1,093) -1,200 2015* 2016 2017 *FY 2015 figures are not IFRS. 2017 at A Glance Table of Contents Company Profile 2x5 MHz 01 04 Governance new spectrum acquisition About Mobily 08 Board of Directors 48 Vision and Values 09 Executive Management 58 Chairman’s Statement 10 Related Party Transactions 60 Rising to the Challenge 12 Compensation and Remuneration 61 Geographic Footprint 14 About Mobily 62 Achievements and Awards 16 Important Events 65 Shareholder Information and Key Forward-looking Statements 66 18 Announcements Social Responsibility 67 46 Shareholders 68 Mobily Elite fourth-batch recruits Dividend Policy 70 -

Using Intrinsic Values in Advertising Campaign: a Social Awareness Approach Associ

مجلة العمارة والفنون والعلوم اﻻنسانية - المجلد الخامس - العدد الرابع والعشرون نوفمبر 2020 Using Intrinsic Values in Advertising Campaign: A Social Awareness Approach Associ. Prof. Dr. Aliaa Turafy Associate Professor in Advertising, Mass Communication Department, Faculty of Al- Alsun & Mass Communication, Misr International University [email protected] Abstract: Materialistic values have become the primary status of most Egyptian society. This may be due to their attempts to satisfy some of their needs by owning things. Many institutions have been able to take advantage of this trend as a mean of selling points, and even using the idea of the ego. Nowadays, the concept of corporate responsibility has been widespread and it can be defined as "the foundation voluntarily by material, or moral contributions undertaken according to the response of the needs and expectations of its internal and external audiences". In addition, most institutions rely on advertising to advertise their products, services, or ideas. Accordingly, the importance of this research is attempting to add intrinsic values in advertising campaign design taking it as an advantage to play a social awareness role and achieve the communicative goals of the advertiser. Intrinsic values represent the value or meaning of the thing in itself, and the fundamental human values that emanate from the individual himself/herself and are not valuables, whereas these values serve the human benefit. The research aims to develop a strategy to help advertising campaigns use the intrinsic values which include social, personal, and environmental values in design of advertising campaign to achieve; first the advertiser’s aims and second the community service of the institution maintaining the moral framework as a social awareness edge for the target audience. -

Download PDF Dossier

Halberd Bastion Pty Ltd ABN: 88 612 565 965 58 Latrobe Terrace, Brisbane Queensland, Australia, 4064 [email protected] Research Dossier: Etisalat Headquarters United Arab Emirates Company Name Emirates Telecommunications Group Company PJSC Ownership Type Publicly Traded Company State/Government Owned Website http://www.etisalat.com Company Overview Etisalat Group is one of the world’s leading telecom groups in emerging markets. Etisalat’s current market cap is over AED 152 billion (42 billion USD). With reported net revenues of AED 52.4 billion and net profit of AED 8.4 billion for 2016, Etisalat ranks amongst the most profitable telecom groups in the world. Its high credit ratings at AA-/Aa3 reflect the company’s strong balance sheet and proven long- term performance. Headquartered in Abu Dhabi, Etisalat was established four decades ago in the UAE as the country’s first telecommunications service provider. An international blue-chip organisation, Etisalat Group provides innovative solutions and services to 162 million subscribers in 16 countries across the Middle East, Asia and Africa. Groups Under Direction The company maintains a significant controlling stake in 1 group companies globally. Group companies are those maintaining a parent relationship to individual subsidiaries and/or mobile network operators. Maroc Telecom Headquarters: Morocco Type: Publicly Traded Company Subsidiaries The company has 6 subsidiaries operating mobile networks. Etisalat Afghanistan Country: Afghanistan 3G Bands: B1 (2100 MHz) 4G Bands: None IoT -

Consolidated Financial Statements 2020 2

Consolidated financial statements Year ended December 31, 2020 This document is a free translation into English of the yearly financial report prepared in French and is provided solely for the convenience of English speaking readers. Significant events 2020 Tax dispute Covid-19 IFRS 16 concerning Health crisis Lease term fiscal years 2005-2006 The effect of the health crisis on the In December 2019, IFRS IC issued On November 13, 2020, the Conseil Group’s business and performance, its final decision on the determination d'État issued a favorable decision on the judgments and assumptions of the enforceable period of leases. a tax dispute in respect of the years made, as well as the main effects of 2005-2006. the crisis on the Group’s consolidated financial statements are The effects of this decision on the presented in Note 3 “Impact of the Group are presented in Note 2.3 As at December 31, 2020, the health crisis linked to the Covid-19 “New standards and interpretations current tax expense includes tax pandemic”. applied from January 1, 2020”. income of 2,246 million euros. Note 3 Note 2.3.1 Note 11.2 Consolidated financial statements 2020 2 Table of contents 7.4 Executive compensation ......................................................... 64 Financial statements Note 8 Impairment losses and goodwill ................................... 64 8.1 Impairment losses................................................................... 64 Consolidated income statement................................................... 4 8.2 Goodwill ................................................................................. 65 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income ...................... 5 8.3 Key assumptions used to determine recoverable amounts ...... 65 Consolidated statement of financial position ................................ 6 8.4 Sensitivity of recoverable amounts .......................................... 67 Note 9 Fixed assets ...............................................................