You Can't Kill Marielle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O Culto Dedicado À Marielle Franco: a Luta Pelos Direitos Humanos Na Igreja Da Comunidade Metropolitana Do Rio De Janeiro (ICM) 1

O culto dedicado à Marielle Franco: a luta pelos direitos humanos na Igreja da Comunidade Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro (ICM) 1 Pedro Costa Azevedo (UENF) Introdução Esta comunicação busca compreender de que forma o discurso religioso da Igreja da Comunidade Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro (ICM) mobiliza sua atuação política sob a perspectiva dos direitos humanos. Para isso, este trabalho analisará o culto ecumênico após o assassinato da vereadora Marielle Franco no ano de 2018, onde foi destacada a pauta dos direitos humanos presente em sua trajetória pessoal e política. O pano de fundo desse acontecimento-chave foi marcado pelo apoio de lideranças religiosas pentecostais à campanha de Jair Bolsonaro no pleito eleitoral desse ano. O receio do retrocesso no campo dos direitos humanos, sobretudo quanto aos direitos sexuais e reprodutivos, colocou em disputa os valores e práticas da ICM-Rio em relação à agenda política dos parlamentares e lideranças do campo religioso e político brasileiro. Assim, este trabalho consiste em elucidar as disputas em torno dos valores da atuação religiosa da ICM-Rio em vista das controvérsias no referido contexto político. Em 2018, quando me dirigi ao trabalho de campo, a ICM-Rio encontrava-se2 na Rua do Senado no Centro da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Em uma sala comercial na área térrea do Edifício Liazzi as portas de enrolar3 erguidas indicavam a realização de atividades e cultos dominicais da ICM, que costumavam ocorrer em uma frequência de uma a duas vezes por semana4. Como a instituição fica em uma região central, a acessibilidade aos cultos e atividades torna-se mais viável para pessoas que venham de diferentes bairros e das cidades situadas na região metropolitana, sobretudo, pela proximidade com a Estação Central do Brasil. -

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America in Latin America Power and Political Evangelicals JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE We are a political foundation that is active One of the most noticeable changes in Latin America in 18 forums for civic education and regional offices throughout Germany. during recent decades has been the rise of the Evangeli- Around 100 offices abroad oversee cal churches from a minority to a powerful factor. This projects in more than 120 countries. Our José Luis Pérez Guadalupe is a professor applies not only to their cultural and social role but increa- headquarters are split between Sankt and researcher at the Universidad del Pacífico Augustin near Bonn and Berlin. singly also to their involvement in politics. While this Postgraduate School, an advisor to the Konrad Adenauer and his principles Peruvian Episcopal Conference (Conferencia development has been evident to observers for quite a define our guidelines, our duty and our Episcopal Peruana) and Vice-President of the while, it especially caught the world´s attention in 2018 mission. The foundation adopted the Institute of Social-Christian Studies of Peru when an Evangelical pastor, Fabricio Alvarado, won the name of the first German Federal Chan- (Instituto de Estudios Social Cristianos - IESC). cellor in 1964 after it emerged from the He has also been in public office as the Minis- first round of the presidential elections in Costa Rica and Society for Christian Democratic Educa- ter of Interior (2015-2016) and President of the — even more so — when Jair Bolsonaro became Presi- tion, which was founded in 1955. National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (Institu- dent of Brazil relying heavily on his close ties to the coun- to Nacional Penitenciario del Perú) We are committed to peace, freedom and (2011-2014). -

Religious Leaders in Politics

International Journal of Latin American Religions https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00123-1 THEMATIC PAPERS Open Access Religious Leaders in Politics: Rio de Janeiro Under the Mayor-Bishop in the Times of the Pandemic Liderança religiosa na política: Rio de Janeiro do bispo-prefeito nos tempos da pandemia Renata Siuda-Ambroziak1,2 & Joana Bahia2 Received: 21 September 2020 /Accepted: 24 September 2020/ # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The authors discuss the phenomenon of religious and political leadership focusing on Bishop Marcelo Crivella from the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (IURD), the current mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the context of the political involvement of his religious institution and the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, selected concepts of leadership are applied in the background of the theories of a religious field, existential security, and the market theory of religion, to analyze the case of the IURD leadership political involvement and bishop/mayor Crivella’s city management before and during the pandemic, in order to show how his office constitutes an important part of the strategies of growth implemented by the IURD charismatic leader Edir Macedo, the founder and the head of this religious institution and, at the same time, Crivella’s uncle. The authors prove how Crivella’s policies mingle the religious and the political according to Macedo’s political alliances at the federal level, in order to strengthen the church and assure its political influence. Keywords Religion . Politics . Leadership . Rio de Janeiro . COVID-19 . Pandemic Palavras-chave Religião . -

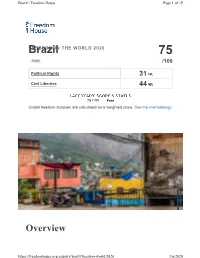

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Urban Black Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense by Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Migolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT ‘Christ the Redeemer Turns His Back on Us:’ Black Urban Struggle in Rio’s Baixada Fluminense By Stephanie Reist Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Mignolo, Supervisor ___________________________ Esther Gabara ___________________________ Gustavo Furtado ___________________________ John French ___________________________ Catherine Walsh ___________________________ Amanda Flaim An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Stephanie Virginia Reist 2018 Abstract “Even Christ the Redeemer has turned his back to us” a young, Black female resident of the Baixada Fluminense told me. The 13 municipalities that make up this suburban periphery of -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Race and Political

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Race and Political Representation in Brazil A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Andrew Janusz Committee in charge: Professor Scott Desposato, Co-Chair Professor Zoltan Hajnal, Co-Chair Professor Gary Jacobson Professor Simeon Nichter Professor Carlos Waisman 2019 Copyright Andrew Janusz, 2019 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Andrew Janusz is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii DEDICATION For my mother, Betty. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vi List of Tables . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita ............................................... x Abstract of the Dissertation . xi Introduction . 1 Chapter 1 The Political Importance of Race . 10 Chapter 2 Racial Positioning in Brazilian Elections . 20 Appendix A . 49 Chapter 3 Ascribed Race and Electoral Success . 51 Appendix A . 84 Chapter 4 Race and Substantive Representation . 87 Appendix A . 118 Appendix B . 120 Chapter 5 Conclusion . 122 Bibliography . 123 v LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.1: Inconsistency in Candidate Responses Across Elections . 27 Figure 2.2: Politicians Relinquish Membership in Small Racial Groups . 31 Figure 2.3: Politicians Switch Into Large Racial Groups . 32 Figure 2.4: Mayors Retain Membership in the Largest Racial Group . 34 Figure 2.5: Mayors Switch Into the Largest Racial Group . 35 Figure 2.6: Racial Ambiguity and Racial Switching . 37 Figure 2.7: Politicians Remain in Large Groups . 43 Figure 2.8: Politicians Switch Into Large Groups . -

“Pacification” for Whom?

“PACIFICATION” FOR WHOM? Marielle Franco MARIELLE PRESENT! Marielle Franco, aged 38, a Rio de Janeiro city councilor elected with 46,502 votes in 2016, was shot dead in an ambush on 14 March 2018. As a black woman, a lesbian and a mother who grew up in the Maré favela, Marielle turned to human rights activism when she was 19 years old and routinely had to contend with machismo, racism and LGBTphobia in her work. Nothing changed when she served as city councilor: shortly after taking office, Marielle was made chair of the Rio de Janeiro City Council Women’s Commission – a job whose results were released three months after her murder.1 Five of the bills she submitted were approved: Bill 17/2017 – Espaço Coruja (“Night Owl”): crèches for parents who work or study at night; Bill 103/2017 – Dia de Thereza de Benguela no Dia da Mulher Negra: a homage to the 18th century black leader Thereza de Benguela to be celebrated on the same date as Black Woman’s Day; Bill 417/2017 – Assédio não é passageiro: a campaign to raise awareness and combat sexual assault and harassment; Bill 515/2017 – Efetivação das Medidas Socioeducativas em Meio Aberto: to guarantee social and educational measures for young offenders; Bill 555/2017 – Dossiê Mulher Carioca: compilation of an annual report with statistics on violence against women. As a long-time vocal opponent of the militarisation of life, her political and academic output demonstrate the strength of someone who knew, from an early age, the devastation caused by institutional violence. -

Political Analysis

POLITICAL ANALYSIS THE CONSEQUENCES OF BRAZILIAN MUNICIPAL ELECTION THE CONSEQUENCES OF than in 2016 (1,035). The PSD won in BRAZILIAN MUNICIPAL ELECTION Belo Horizonte (Alexandre Kalil) and Campo Grande (Marquinhos Trad). The results of the municipal elections showed, in general, that the voter sought candidates more distant from Left reorganization the extremes and with experience in management. For the first time since democratization, PT will not govern any capital in Brazil. In numbers, DEM and PP parties were He lost in Recife and Vitória in the sec- the ones that gained more space, with ond round. The party suffers from de- good performances from PSD, PL, and laying the renewal process and, little by Republicans. The polls also confirmed little, loses its hegemony. In this elec- the loss of prefectures by left-wing par- tion, they saw PSOL win in Belém and ties, especially the PT from former reach the second round in São Paulo. president Lula. PDT and PSB, on the other hand, guar- anteed good spaces in the capitals, es- pecially in the Northeast. Moderation The scenario encourages the reorgani- The municipal election, especially in zation of the left, with the possibility of large urban centers, acclaimed candi- candidates from other parties being the dates who adopted a moderate stance protagonists. It remains to be seen and tried to show themselves prepared whether the PT, which is still the main for the post. Outsiders were not as party in the field, will self-criticize and successful as two years ago, in the las agree to support a name from another general election in Brazil. -

The Murder of Brazilian Councilwoman and Activist Marielle Franco

Analyzing polarization in Twitter: The murder of Brazilian councilwoman and activist Marielle Franco Abstract. Social media has allowed people to publicly express, at near zero cost, their opinions and emotions on a wide range of topics. This recent scenario allows the analysis of social media platforms to several purposes, such as predicting elections, exploiting influential users or understanding the polarization of public opinion on polemic topics. In this work, we analyze the Brazilian public percep- tion related to the murder of a Rio councilwoman, Marielle Franco, member of a left-wing party and human-rights activist. We propose a polarity score to capture whether the tweet is positive or negative and then we analyze the score evolution over the time, after the murder. Finally, we evaluate our approach correlating the polarity score with human judgment over a randomly sampled set of tweets. Our preliminary results show how to measure polarity on public opinion using a weighted dictionary and how it changes over time. Keywords: Social media, Sentiment analysis, Opinion Mining. 1 Introduction Over the last years, an increasing number of people actively use the Internet to exchange information and convey emotions, allowing studies that examine how technology can influence people’s feelings. Social media platforms have become an important source of data to capture those emotions, opinions and sentiments on several topics and debates – from the Mediterranean refugee’s crisis (Coletto et al., 2016) to political leanings (Conover et al., 2011) (Tumasjan et al., 2010). Twitter platform is especially powerful because of its very nature, which encourages people to have public conversations and debates, sharing their thoughts with others, creating solidary networks or politically engaged movements. -

The Republic in Crisis and Future Possibilities

DOI: 10.1590/1413-81232017226.02472017 1747 The republic in crisis and future possibilities DEBATE José Maurício Domingues 1 Abstract This text gives a brief reconstruction of the process of impeachment of Brazil’s Presi- dent Dilma Rousseff, which was a ‘coup’ effected through parliament, and situates it at the end of three periods of politics in the Brazilian republic: the first, broader, and democratizing; the second, the age of the PT (Workers’ Party) as the force with the hegemony on the left; and the third, shorter, the cycle of its governments. Together, these phases constitute a crisis of the republic, although not a rupture of the country’s institutional structure, nor a ‘State of Exception’. The paper puts forward three main issues: the developmentalist project implemented by the governments of the PT, in alliance with Brazil’s construction companies; the role of the judiciary, and in particular of ‘Oper- ation Carwash’; and the conflict-beset relation- ship between the new evangelical churches and the LGBT social movements. The essay concludes with an assessment of the defeat and isolation of the left at this moment, and also suggests that democracy, in particular, could be the kernel of a renewed project of the left. Key words Political cycles, Impeachment, Left, democracy, Development 1 Centro de Estudos Estratégicos, Fiocruz. Av. Brasil 4036/10º, Manguinhos. 21040-361 Rio de Janeiro RJ Brasil. [email protected] 1748 Domingues JM Isolation and impeachment her adversary from the PSDB party. Thus, she lost a considerable part of the social base that Brazil is at present immersed in one of the most elected her. -

The Perfect Misogynist Storm and the Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’S Political Crisis

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 Issue 8 Issue #2 (of 2) Women’s Movements and the Shape of Feminist Theory and Praxis in Article 6 Latin America October 2019 The Perfect Misogynist Storm and The Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’s Political Crisis Cara K. Snyder Cristina Scheibe Wolff Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, Cara K. and Wolff, Cristina Scheibe (2019). The Perfect Misogynist Storm and The Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’s Political Crisis. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(8), 87-109. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss8/6 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Perfect Misogynist Storm and The Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’s Political Crisis By Cara K. Snyder1 and Cristina Scheibe Wolff2 Abstract In Brazil, the 2016 coup against Dilma Rousseff and the Worker’s Party (PT), and the subsequent jailing of former PT President Luis Ignacio da Silva (Lula), laid the groundwork for the 2018 election of ultra-conservative Jair Bolsonaro. In the perfect storm leading up to the coup, the conservative elite drew on deep-seated misogynist discourses to oust Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s progressive first woman president, and the Worker’s Party she represented. -

The Transformative Commitment of Cities and Territories to Generation Equality Index

A Global Feminist Municipal Movement THE TRANSFORMATIVE COMMITMENT OF CITIES AND TERRITORIES TO GENERATION EQUALITY INDEX PREFACE INTRODUCTION SECTION 1. Institutional frameworks and representation: Women’s leadership in the local sphere 1.1. Where are the women in Local Governments? Still a long way to achieving parity 1.2. Local territories as catalysts for women’s political participation SECTION 2. When the personal is political 2.1. The importance of the trajectory 2.2. Dismantling stereotypes and overcoming barriers to advance rights SECTION 3. What agendas are women in local power driving? A strategic look towards the future 3.1. Constructing democratic and inclusive morphologies in local territories: The key points guiding the political agenda of the Feminist Municipal Movement 3.2. Cities and territories that care and sustain the fabric of life: The public issues at the heart of the political agenda SECTION 4. The advance of the Feminist Municipal Movement at the global scale: The table is set 2 Emilia Saiz, Secretary General of United Cities PREFACE: and Local Governments (UCLG) “Women represent more than half of the world population. Nevertheless, they continue to be one of the populations most exposed to violence of all sorts and pressing discrimination. (…) The status of women is one of ‘vulnerability’ or ‘invisibility’ even though they are proactive and effective actresses of transformation”. With these words of the Durban Manifesto on the Future of Equality, local and regional governments gathered within UCLG made a clear call on this challenge and reminded us how we are still far away from the necessary progress on gender equality, 26 years after the adoption of the Beijing Platform for Action.