Influence of German Literature Upon Modern Music Since 1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Ritter (Geb

Alexander Ritter (geb. Narva, 27. Juni 1833 - gest. München, 12. April 1896) Kaiser Rudolfs Ritt zum Grabe Alexander Ritter zählt zu den eher vernachlässigten Mitgliedern der Neudeutschen Schule um Liszt und Wagner, trotz seiner Bedeutung für die Übermittlung der Idee orchestraler Programm-Musik von Liszt zu Richard Strauss und die Einführung junger Komponisten in die Philosophie von Schopenhauer sowie die Ästhetik hinter Wagners Musikdramen. Geboren am 27. Juni in Narva / Russland (heute Estland), verlor er seinen Vater in jungen Jahren und zog 1841 nach Dresden, wo er Klassenkamerad und Freund von Hans von Bülow wurde. Sein Grundschullehrer dort war der Konzert-meister Franz Strauss - in Folge studierte er zwischen 1849 und 1851 am Leipziger Konservatorium, unter anderen bei Ferdinand David (Violine) und Ernst Friedrich Richter (Theorie). Es war in Dresden, wo seine Familie erste Kontakte zu Richard Wagner knüpfte: Mutter Julie traf ihn kurz bevor der Komponist nach Zürich flüchtete, während Bruder Karl ihm dorthin folgte und sein (mässig erfolgreicher) Schützling wurde. Julie, die über ausreichende finanzielle Mittel verfügte, tat sich mit Jessie Laussot zusammen, um Wagner mit einer jährlichen Subvention zu unterstützen, die Julie bis 1859 auch fortführte, nachdem Laussot 1851 gezwungen war, sich von der Vereinbarung zurückzuziehen. Alexander selbst trat in nähere Beziehung zu Wagner durch seine Verlobung (1852) und Heirat (1854) mit der Schauspielerin Franziska Wagner, einer Nichte des Komponisten. Ritter hatte Liszt bereits in 1844 in Dresden spielen gehört, zu welcher Gelegenheit er den Pianisten um einen seiner Handschuhe (für seine Schwester Emilie) bat. Schliesslich stellte ihn Bülow ein weiteres mal Liszt vor, der 1854 dem vielversprechenden Violinisten eine Stelle als zweiter Konzertmeister beim Weimarer Hoforchester anbot. -

WR 16Mar 1928 .Pdf

World -Radio, March 16, 1928. P n n rr rrr 1 itiol 111111 SPECIAL IRISHNUMBER Registered at the.G.P.O. Vol. VI.No. 138. as a Newspaper. FRIDAY. MARCH 16, 1928. Two Pence. WORLD -RADIO 8 tEMEN Station Identification Panel- Konigswusterhausen (Zeesen). Germany REC GE (Revised) Wavelength : 125o in. Frequency : 240 kc. Power :35 kw. H. T. BATTERY Approximate Distance from London : 575 miles. (Lea-melte Tide) Call " Achtung !Achtung !Hier die Deutsche Welle, Berlin,-Konigswus- terhausen."(Sometimes wavelength POSSESSES all the advantages of a DRY BATTERY given :" . auf Welle zwolf hun- dert and fiinfzig," when callre- -none of the disadvantages of the ordinary WET peated.)When relaying :" Ferner Ubertragimgauf "... (nameof BATTERY. relaying stations). Interval Signal:Metronome.Forty beats in ten seconds. 1. Perfectly noiseless, clean SpringConnections,no IntervalCall :" Achtung !Konigs. and reliable. 4.soldering. wusterhausen.DerVortragvon [name of lecturer]uber[titleof 5. No "creeping of salts. lecture]ist beendet.Auf Wieder- 2. Unspillable. Easily recharged, & main- 'toren in . Minuten."When 6. relaying :`& Auf Wiederhorenfur 3No attention required until tains full energy through- Konigswusterhausen in . exhausted. out the longest programme. Minuten ;fur Breslau and Gleiwitz [or as the case may be] nach eigenem Programm." 711,2 ails are null: in thefoll,n,ing three sizes: Own transmissionsandrelays.In eveningrelaysfromotherstations. H.T.1.Small ... 8d. each. Closes down at the same time as the relaying station. H.T.2.Large ... 10d. each. H.T.3.Extra Large 1:- each. (Copyright) A booklet containing alargenumberof these Guaranteed to give I a,volts per cell. panels canbeobtainedof B.B.C.Publications, Savoy Hrll, W. -

Elsa Bernstein's Dämmerung and the Long Shadow of Henrik Ibsen

Birkbeck College University of London MA in Modern German Studies Elsa Bernstein’s Dämmerung and the long shadow of Henrik Ibsen Manfred Pagel Assessed essay (4000 words): April 2006 Core Course: History in German Literature Course Co-ordinator: Dr Anna Richards M. Pagel Introduction Nomen est omen. When the young Elsa Bernstein (1866-1949) decided to adopt a male pseudonym at an early stage of her writing career, as many women authors did in the late 19th century, she chose one that made an unmistakable allusion to the contemporary Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906). Her assumed nom de plume of “Ernst Rosmer” an “audible echo of Ibsen”1, clearly owed its invention to his play Rosmersholm2. In this way she signalled her literary affinity with the dominant themes and style (described as Naturalism) favoured by Ibsen during the 1880s and 1890s, when he was establishing his enduring reputation as a masterful writer of social drama. The pen-name, Susanne Kord writes, “defined her as a disciple of one of the major playwrights of her time and simultaneously allied her with the German naturalist movement, which was centrally indebted to Ibsen’s dramatic work”3. Bernstein’s five-act play Dämmerung4, originally published in 1893, will serve here as reference text in an attempt to explore some aspects of her subject matter and treatment that may be at least partly attributable to Ibsen’s influence. The characterisation of the two main female roles, in particular, will be considered because the evolving position of women in modern society and the related issue of feminist emancipation from traditional bourgeois constraints formed a recurring topic in Ibsen’s plays, such as A Doll’s House5, Hedda Gabler6, and Little Eyolf7. -

Die Deutsche Nationalhymne

Wartburgfest 1817 III. Die deutsche Nationalhymne 1. Nationen und ihre Hymnen Seit den frühesten Zeiten haben Stämme, Völker und Kampfeinheiten sich durch einen gemeinsamen Gesang Mut zugesungen und zugleich versucht, den Gegner zu schrecken. Der altgriechische Päan ist vielleicht das bekannteste Beispiel. Parallel zum Aufkommen des Nationalismus entwickelten die Staaten nationale, identitätsstiftende Lieder. Die nieder- ländische Hymne stammt aus dem 16 Jahrhundert und gilt als die älteste. Wilhelmus von Nassawe bin ich von teutschem blut, dem vaterland getrawe bleib ich bis in den todt; 30 ein printze von Uranien bin ich frey unverfehrt, den könig von Hispanien hab ich allzeit geehrt. Die aus dem Jahre 1740 stammen Rule Britannia ist etwas jünger, und schon erheblich nationalistischer. When Britain first, at Heaven‘s command Arose from out the azure main; This was the charter of the land, And guardian angels sang this strain: „Rule, Britannia! rule the waves: „Britons never will be slaves.“ usw. Verbreitet waren Preisgesänge auf den Herrscher: Gott erhalte Franz, den Kaiser sang man in Österreich, God save the king in England, Boshe chrani zarja, was dasselbe bedeutet, in Rußland. Hierher gehören die dänische Hymne Kong Christian stod ved højen mast i røg og damp u. a. Die französische Revolution entwickelte eine Reihe von Revolutionsge- sängen, die durchweg recht brutal daherkommen, wie zum Beispiel das damals berühmte Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira, Les aristocrates à la lanterne! Ah! ça ira, ça ira, ça ira, Les aristocrates on les pendra! also frei übersetzt: Schaut mal her, kommt zuhauf, wir hängen alle Fürsten auf! Auch die blutrünstige französische Nationalhymne, die Mar- seillaise, stammt aus dieser Zeit: Allons enfants de la patrie. -

The Orchestra in History

Jeremy Montagu The Orchestra in History The Orchestra in History A Lecture Series given in the late 1980s Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2017 Contents 1 The beginnings 1 2 The High Baroque 17 3 The Brandenburg Concertos 35 4 The Great Change 49 5 The Classical Period — Mozart & Haydn 69 6 Beethoven and Schubert 87 7 Berlioz and Wagner 105 8 Modern Times — The Age Of The Dinosaurs 125 Bibliography 147 v 1 The beginnings It is difficult to say when the history of the orchestra begins, be- cause of the question: where does the orchestra start? And even, what is an orchestra? Does the Morley Consort Lessons count as an orchestra? What about Gabrieli with a couple of brass choirs, or even four brass choirs, belting it out at each other across the nave of San Marco? Or the vast resources of the Striggio etc Royal Wedding and the Florentine Intermedii, which seem to have included the original four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie, or at least a group of musicians popping out of the pastry. I’m not sure that any of these count as orchestras. The Morley Consort Lessons are a chamber group playing at home; Gabrieli’s lot wasn’t really an orchestra; The Royal Wed- dings and so forth were a lot of small groups, of the usual renais- sance sorts, playing in turn. Where I am inclined to start is with the first major opera, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Even that tends to be the usual renaissance groups taking turn about, but they are all there in a coherent dra- matic structure, and they certainly add up to an orchestra. -

Johannes Brahms and Hans Von Buelow

The Library Chronicle Volume 1 Number 3 University of Pennsylvania Library Article 5 Chronicle October 1933 Johannes Brahms and Hans Von Buelow Otto E. Albrecht Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/librarychronicle Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Albrecht, O. E. (1933). Johannes Brahms and Hans Von Buelow. University of Pennsylvania Library Chronicle: Vol. 1: No. 3. 39-46. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/librarychronicle/vol1/iss3/5 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/librarychronicle/vol1/iss3/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. not later than 1487. Incidentally it may be mentioned that the Gesamtkatalog fully records a "Seitengetreuer Nach- druck" (mentioned by Proctor) as of [Strassburg, Georg Husner, um 1493/94]. The two editions (of which Dr. Ros- enbach's gift is the original) have the same number of leaves but the register of signatures is different. And now in 1933 comes the Check list of fifteenth century books in the New- berry Library, compiled by Pierce Butler, capping the struc- ture with the date given as [1488] and the printer Johann Priiss, OTHER RECENT GIFTS Through the generosity of Mr. Joseph G. Lester the Library has received a copy of Lazv Triumphant, by Violet Oakley. The first volume of this beautifully published work contains a record of the ceremonies at the unveiling of Miss Oakley's mural paintings, "The Opening of the Book of the Law," in the Supreme Court room at Harrisburg, and the artist's journal during the Disarmament Conference at Gen- eva. -

SOMMARIO Una Premessa Sul Puro Umano E Wagner Oggi Il Puro

SOMMARIO L'ONTOLOGIA DELL'UMANO Una premessa sul puro umano e Wagner oggi Il puro umano VII L'intreccio XVII Wagner oggi XX RICHARD WAGNER LA POETICA DEL PURO UMANO A PARIGI: BERLIOZ, LISZT, WAGNER Un intreccio affascinante La malinconia dell'essere: la poetica della Romantik 3 La cultura musicale nella Parigi degli anni Trenta, una fìtta trama di relazioni 16 Berlioz, emancipazione del parametro timbrico 33 Liszt e Chopin, ricerca strumentale e compositiva 45 Wagner, «Un musicista tedesco a Parigi» 71 IN GERMANIA, LA POETICA DEL PURO UMANO Trame di passione Le composizioni strumentali giovanili 101 Mendelssohn e gli Schumann, incomprensioni e polemiche 123 I primi abbozzi teatrali e Le fate 133 II divieto d'amare, «Canto, canto e ancora canto, o tedeschi!» 144 Rienzi, «Armi», «Bandiere», «Onore», «Libertà» 153 L'Olandese volante, «Ah! Superbo oceano!» 170 http://d-nb.info/1024420035 Tannhàuser, «Potete voi tutti scoprirmi la natura dell'amore?» 196 Lohengrin, «Mai non dovrai domandarmi» 222 I Wibelunghi, i moti rivoluzionari, L'arte e la rivoluzione, Gesù di Nazareth 2S3 SCHOPENHAUER E LE «DIVINE PARTITURE» Gli scritti e i capolavori L'arrivo in Svizzera, Wieland il fabbro, Liszt, i brani pianistici, Berlioz 269 L'opera d'arte dell'avvenire, Il giudaismo nella musica, Opera e dramma, Una comunicazione ai miei amici 290 Schopenhauer, «Mi sentii subito profondamente attratto» 314 Wesendonck-Lieder, Parigi, Rossini, Ludwig II 322 Tristan, «Naufragare / affondare / inconsapevolmente / suprema letizia!» 359 Il libro bruno, La mia vita, Il -

Richard Wagner(1813 – 1883)

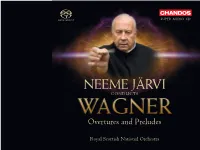

SUPER AUDIO CD NEEME JÄRVI CONDUCTS Overtures and Preludes Royal Scottish National Orchestra Richard Wagner, May 1865 May Wagner, Richard Photograph by Josef Albert (1825 – 1886) / AKG Images, London / Imagno Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883) Overtures and Preludes 1 Overture to ‘Die Feen’, WWV 32* 10:48 Adagio – Un poco meno adagio – Tempo I – Allegro con molto fuoco – Più allegro 2 Overture to ‘Columbus’, WWV 37† 8:02 Edited 1907 by Felix Mottl (1856 – 1911) as concert overture with the title Christoph Columbus Allegro molto agitato – Andante maestoso – Tempo I – Andante maestoso – Tempo I – Andante maestoso – Tempo I – Andante – Tempo I – Andante – Presto 3 Overture to ‘Das Liebesverbot’, WWV 38* 8:10 Molto vivace – Allegro con fuoco – Presto 4 Overture to ‘Rienzi, der Letzte der Tribunen’, WWV 49‡ 11:16 Molto sostenuto e maestoso – Allegro energico – Un poco più vivace – Molto più stretto 3 5 Eine Faust-Ouvertüre, WWV 59† 11:03 Sehr gehalten – Sehr bewegt – Sehr allmählich das Tempo etwas zurückhalten – A tempo – Wild 6 Overture to ‘Der fliegende Holländer’, WWV 63‡ 11:00 Allegro con brio – Andante – Animando un poco – Tempo I – Molto animato – Un poco ritenuto [not previously released] 7 Prelude to Act III of ‘Lohengrin’, WWV 75* 3:04 Sehr lebhaft 8 Prelude to ‘Tristan und Isolde’, WWV 90* 6:43 Langsam und schmachtend 9 Prelude to ‘Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg’, WWV 96† 8:56 Sehr mäßig bewegt – Bewegt, doch immer noch etwas breit – Mäßig im Hauptzeitmaß – Im mäßigen Hauptzeitmaß – Sehr gewichtig TT 80:00 Royal Scottish National Orchestra William Chandler* • Peter Thomas† • Maya Iwabuchi‡ leaders Neeme Järvi 4 Wagner: Overtures and Preludes Overture to ‘Die Feen’ Overture to ‘Columbus’ / Eine Faust- Even if the overall style of Wagner’s first great Ouvertüre romantic, although less well-known, opera, That Wagner wrote instrumental music for Die Feen, WWV 32 (1833 – 34), based on a spoken drama appears as no accident in the La donna serpente by Carlo Gozzi, owes its essentials light of his later œuvre. -

Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15

Library of Congress Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15 Cutting Marsh (From photograph loaned by John N. Davidson.) Wisconsin State historical society. COLLECTIONS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY. OF WISCONSIN EDITED AND ANNOTATED BY REUBEN GOLD THWAITES Secretary and Superintendent of the Society VOL. XV Published by Authority of Law MADISON DEMOCRAT PRINTING COMPANY, STATE PRINTER 1900 LC F576 .W81 2d set The Editor, both for the Society and for himself, disclaims responsibility for any statement made either in the historical documents published herein, or in articles contributed to this volume. 1036011 18 N43 LC CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS. Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.7689d Library of Congress THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SERIAL RECORD NOV 22 1943 Copy 2 Page. Cutting Marsh Frontispiece. Officers of the Society, 1900 v Preface vii Some Wisconsin Indian Conveyances, 1793–1836. Introduction The Editor 1 Illustrative Documents: Land Cessions—To Dominique Ducharme, 1; to Jacob Franks, 3; to Stockbridge and Brothertown Indians, 6; to Charles Grignon, 19. Milling Sites—At Wisconsin River Rapids, 9; at Little Chute, 11; at Doty's Island, 14; on west shore of Green Bay, 16; on Waubunkeesippe River, 18. Miscellaneous—Contract to build a house, 4; treaty with Oneidas, 20. Illustrations: Totems—Accompanying Indian signatures, 2, 3, 4. Sketch of Cutting Marsh. John E. Chapin, D. D. 25 Documents Relating to the Stockbridge Mission, 1825–48. Notes by William Ward Wight and The Editor. 39 Illustrative Documents: Grant—Of Statesburg mission site, 39. Letters — Jesse Miner to Stockbridges, 41; Jeremiah Evarts to Miner, 43; [Augustus T. -

Riccardo Muti Conductor Michele Campanella Piano Eric Cutler Tenor Men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe Director Wagne

Program ONE huNdrEd TwENTy-FirST SEASON Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Friday, September 30, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, October 1, 2011, at 8:00 Tuesday, October 4, 2011, at 7:30 riccardo muti conductor michele Campanella piano Eric Cutler tenor men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe director Wagner Huldigungsmarsch Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major Allegro maestoso Quasi adagio— Allegretto vivace— Allegro marziale animato MiChElE CampanellA IntErmISSIon Liszt A Faust Symphony Faust: lento assai—Allegro impetuoso Gretchen: Andante soave Mephistopheles: Allegro vivace, ironico EriC CuTlEr MEN OF ThE Chicago SyMPhONy ChOruS This concert series is generously made possible by Mr. & Mrs. Dietrich M. Gross. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Mr. & Mrs. John Giura for their leadership support in partially sponsoring Friday evening’s performance. CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PhilliP huSChEr ne hundred years ago, the Chicago Symphony paid tribute Oto the centenary of the birth of Franz Liszt with the pro- gram of music Riccardo Muti conducts this week to honor the bicentennial of the composer’s birth. Today, Liszt’s stature in the music world seems diminished—his music is not all that regularly performed, aside from a few works, such as the B minor piano sonata, that have never gone out of favor; and he is more a name in the history books than an indispensable part of our concert life. -

200 Anos De Franz Liszt: II. Transcrições E Experiências Harmônicas

200 anos de Franz Liszt: II. Transcrições e Experiências harmônicas Transcrições “Franz Liszt, am Flügel phantasieren”, pintura de 1840 de Josef Danhauser A metade da obra catalogada de Liszt (no total de quase 1000) são transcrições das obras de outros compositores para piano solo – como sinfonias, canções e obras camerísticas. Mas Liszt é o primeiro pianista a dar à transcrição um papel que vai muito além de uma “redução” funcional de podermos ver uma obra grandiosa resumida em duas claves, pois ele transforma a transcrição em uma verdadeira tradução da obra para uma nova linguagem, a linguagem do piano. São famosas as suas transcrições das sinfonias de Beethoven, mas há também a transcrição da Sinfonia “Fantástica” de Berlioz, do “Liebestod” do Tristão e Isolda de Wagner, de diversas canções de Schubert e até do Requiem de Mozart. O que chama a atenção nas transcrições não é apenas que elas acabaram contribuindo para a própria história da escrita pianística ao buscarem recursos que dessem conta de outras sonoridades, texturas e dimensões, mas também como Liszt concebia a transcrição como uma obra própria, que deveria se justificar independentemente da obra original e por isso demandava necessidades próprias, que ele poderia resolver com compassos totalmente novos. Como exemplo, compare-se a belíssima canção “Kriegers Ahnung” do ciclo Schwanengesang (1828) de Schubert: [audio:http://euterpe.blog.br/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Schubert-Lieder-D-95 7-Schwanengesang-02.-Kriegers-Ahnung-D.-Fischer-Dieskau-G.- Moore-1957.mp3|titles=Schubert – Lieder D 957 ‘Schwanengesang’ – 02. Kriegers Ahnung (D. Fischer-Dieskau & G. Moore – 1957)] O libretto em alemão seguido de uma tradução em português pode ser acessado aqui. -

Im Nonnengarten : an Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907 Michelle Stott Aj Mes

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Resources Supplementary Information 1997 Im Nonnengarten : An Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907 Michelle Stott aJ mes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources Part of the German Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation James, Michelle Stott, "Im Nonnengarten : An Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907" (1997). Resources. 2. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Supplementary Information at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Resources by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. lm N onnengarten An Anthology of German Women's Writing I850-I907 edited by MICHELLE STOTT and JOSEPH 0. BAKER WAVELAND PRESS, INC. Prospect Heights, Illinois For information about this book, write or call: Waveland Press, Inc. P.O. Box400 Prospect Heights, Illinois 60070 (847) 634-0081 Copyright © 1997 by Waveland Press ISBN 0-88133-963-6 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 765432 Contents Preface, vii Sources for further study, xv MALVIDA VON MEYSENBUG 1 Indisches Marchen MARIE VON EBNER-ESCHENBACH 13 Die Poesie des UnbewuBten ADA CHRISTEN 29 Echte Wiener BERTHA VON