Alaska Park Science Anchorage, Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTES on the BIRDS of CHIRIKOF ISLAND, ALASKA Jack J

NOTES ON THE BIRDS OF CHIRIKOF ISLAND, ALASKA JACK J. WITHROW, University of Alaska Museum, 907 Yukon Drive, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Isolated in the western Gulf of Alaska 61 km from nearest land and 74 km southwest of the Kodiak archipelago, Chirikof Island has never seen a focused investigation of its avifauna. Annotated status and abundance for 89 species recorded during eight visits 2008–2014 presented here include eastern range extensions for three Beringian subspecies of the Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus semidiensis), Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia sanaka), and Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (Leucost- icte tephrocotis griseonucha). A paucity of breeding bird species is thought to be a result of the long history of the presence of introduced cattle and introduced foxes (Vulpes lagopus), both of which persist to this day. Unique among sizable islands in southwestern Alaska, Chirikof Island (55° 50′ N 155° 37′ W) has escaped focused investigations of its avifauna, owing to its geographic isolation, lack of an all-weather anchorage, and absence of major seabird colonies. In contrast, nearly every other sizable island or group of islands in this region has been visited by biologists, and they or their data have added to the published literature on birds: the Aleutian Is- lands (Gibson and Byrd 2007), the Kodiak archipelago (Friedmann 1935), the Shumagin Islands (Bailey 1978), the Semidi Islands (Hatch and Hatch 1983a), the Sandman Reefs (Bailey and Faust 1980), and other, smaller islands off the Alaska Peninsula (Murie 1959, Bailey and Faust 1981, 1984). With the exception of most of the Kodiak archipelago these islands form part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (AMNWR), and many of these publications are focused largely on seabirds. -

Ocean Shore Management Plan

Ocean Shore Management Plan Oregon Parks and Recreation Department January 2005 Ocean Shore Management Plan Oregon Parks and Recreation Department January 2005 Oregon Parks and Recreation Department Planning Section 725 Summer Street NE Suite C Salem Oregon 97301 Kathy Schutt: Project Manager Contributions by OPRD staff: Michelle Michaud Terry Bergerson Nancy Niedernhofer Jean Thompson Robert Smith Steve Williams Tammy Baumann Coastal Area and Park Managers Table of Contents Planning for Oregon’s Ocean Shore: Executive Summary .......................................................................... 1 Chapter One Introduction.................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter Two Ocean Shore Management Goals.............................................................................19 Chapter Three Balancing the Demands: Natural Resource Management .......................................23 Chapter Four Balancing the Demands: Cultural/Historic Resource Management .........................29 Chapter Five Balancing the Demands: Scenic Resource Management.........................................33 Chapter Six Balancing the Demands: Recreational Use and Management .................................39 Chapter Seven Beach Access............................................................................................................57 Chapter Eight Beach Safety .............................................................................................................71 -

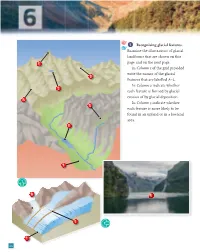

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Population Assessment, Ecology and Trophic Relationships of Steller Sea Liorq in the Gulf of Alaska

Al'lNUAL REPORT Contract #03-5-022-69 Research Unit #243 1 April 1978 - 31 Marc~ 1979 Pages: Population Assessment, Ecology and Trophic Relationships of Steller Sea LiorQ in the Gulf of Alaska Principal Investigators: Donald Calkins, Marine Mammal Biologist Kenneth Pitcher, Marine ~~mmal Biologist Alaska Department of Fish and Game 333 Raspberry Road Anchorage, Alaska 99502 Assisted by: Karl Schneider Dennis McAllister Walt Cunningham Susan Stanford Dave Johnson Louise Smith Paul Smith Nancy Murray TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction. • . i Steller Sea lions in the Gulf of Alaska (by Donald Calkins). 3 Breeding Rookeries and Hauling Areas . 3 I. Surveys • . 3 II. Pup counts. 4 Distribution and Movements . 10 Sea Otter Distribution and Abundance in the Southern Kodiak Archipelago and the Semidi Islands (by Karl Schneider). • • • • 24 Summary •••••• 24 Introduction • • • 25 Kodiak Archipelago 26 Background • • • • . 26 Methods•.•••. 27 Results and discussion • • • • • . 28 1. Distribution••• 30 2. Population size •••••. 39 3. Status. 40 4. Future. 41 Semidi Islands 43 Background • • 43 Methods ••••••••• 43 Results and discussion • 44 Belukha Whales in Lower Cook Inlet (by Nancy Murray) . • • • • • 47 Distribution and Abundance • 47 Habitat••..•••• 50 Population Dynamics •• 54 Food Habits•••••.••. 56 Behavior • . 58 Literature Cited. 59 Introduction This project is a detailed study of the population dynamics, life history and some aspects of the ecology of the Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus). In addition to the sea lion investigations, the work has been expanded to include an examination of the distribution and abundance of belukha whales (Detphinapterus Zeu~dS) in Cook Inlet and the distribution and abundance of sea otters (Enhydra lutris) near the south end of the Kodiak Archipelago. -

Seward Historic Preservation Plan

City of Seward City Council Louis Bencardino - Mayor Margaret Anderson Marianna Keil David Crane Jerry King Darrell Deeter Bruce Siemenski Ronald A. Garzini, City Manager Seward Historic Preservation Commissioners Doug Capra Donna Kowalski Virginia Darling Faye Mulholland Jeanne Galvano Dan Seavey Glenn Hart Shannon Skibeness Mike Wiley Project Historian - Anne Castellina Community Development Department Kerry Martin, Director Rachel James - Planning Assistant Contracted assistance by: Margaret Branson Tim Sczawinski Madelyn Walker Funded by: The City of Seward and the Alaska Office of History and Archaeology Recommended by: Seward Historic Preservation Commission Resolution 96-02 Seward Planning and Zoning Commission Resolution 96-11 Adopted by: Seward City Council Resolution 96-133 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Plan ..............................................................................................................1 Method .................................................................................................................................2 Goals for Historic Preservation............................................................................................3 Community History and Character ..................................................................................................4 Community Resources...................................................................................................................20 -

Characterisation and Prediction of Large-Scale, Long-Term Change of Coastal Geomorphological Behaviours: Final Science Report

Characterisation and prediction of large-scale, long-term change of coastal geomorphological behaviours: Final science report Science Report: SC060074/SR1 Product code: SCHO0809BQVL-E-P The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. This report is the result of research commissioned by the Environment Agency’s Science Department and funded by the joint Environment Agency/Defra Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Research and Development Programme. Published by: Author(s): Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Richard Whitehouse, Peter Balson, Noel Beech, Alan Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD Brampton, Simon Blott, Helene Burningham, Nick Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 Cooper, Jon French, Gregor Guthrie, Susan Hanson, www.environment-agency.gov.uk Robert Nicholls, Stephen Pearson, Kenneth Pye, Kate Rossington, James Sutherland, Mike Walkden ISBN: 978-1-84911-090-7 Dissemination Status: © Environment Agency – August 2009 Publicly available Released to all regions All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Keywords: Coastal geomorphology, processes, systems, The views and statements expressed in this report are management, consultation those of the author alone. The views or statements expressed in this publication do not necessarily Research Contractor: represent the views of the Environment Agency and the HR Wallingford Ltd, Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxon, Environment Agency cannot accept any responsibility for OX10 8BA, 01491 835381 such views or statements. -

Kenai Peninsula Area – Units 7 & 15

Kenai Peninsula Area – Units 7 & 15 PROPOSAL 156 - 5 AAC 85.045. Hunting seasons and bag limits for moose. Shorten the moose seasons in Unit 15 as follows: Go back to a September season, with the archery season starting on September 1, running for one week with a two week rifle season following. What is the issue you would like the board to address and why? Moose hunting starts too early. The weather is too warm. Antler restrictions due to lack of bulls. Shorten the season. Three weeks rather than six is plenty of moose hunting opportunity considering the lack of mature bulls. There will be better meat and less spoilage. Antlers are still growing in archery season. Hunters will need to butcher moose the day they are harvested. PROPOSED BY: Joseph Ross (EG-C14-193) ****************************************************************************** PROPOSAL 157 - 5 AAC 85.045. Hunting seasons and bag limits for moose. Change the general bull moose season dates in Unit 15 to September 1-30 as follows: Move the season forward ten days, changing the Unit 15 general bull moose harvest dates to September 1-30, so a much higher percentage of harvested meat will make it back to hunters' homes to be good table fare. What is the issue you would like the board to address and why? At issue is the preservation of moose meat in Unit 15. It is so warm and humid during the season that moose harvests can turn into monumental struggles to properly care for fresh meat. The culprits are heat, moisture, and flies, each singularly able to ruin a harvest in a matter of a day or two. -

Glacier Mass Balance This Summary Follows the Terminology Proposed by Cogley Et Al

Summer school in Glaciology, McCarthy 5-15 June 2018 Regine Hock Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks Glacier Mass Balance This summary follows the terminology proposed by Cogley et al. (2011) 1. Introduction: Definitions and processes Definition: Mass balance is the change in the mass of a glacier, or part of the glacier, over a stated span of time: t . ΔM = ∫ Mdt t1 The term mass budget is a synonym. The span of time is often a year or a season. A seasonal mass balance is nearly always either a winter balance or a summer balance, although other kinds of seasons are appropriate in some climates, such as those of the tropics. The definition of “year” depends on the measurement method€ (see Chap. 4). The mass balance, b, is the sum of accumulation, c, and ablation, a (the ablation is defined here as negative). The symbol, b (for point balances) and B (for glacier-wide balances) has traditionally been used in studies of surface mass balance of valley glaciers. t . b = c + a = ∫ (c+ a)dt t1 Mass balance is often treated as a rate, b dot or B dot. Accumulation Definition: € 1. All processes that add to the mass of the glacier. 2. The mass gained by the operation of any of the processes of sense 1, expressed as a positive number. Components: • Snow fall (usually the most important). • Deposition of hoar (a layer of ice crystals, usually cup-shaped and facetted, formed by vapour transfer (sublimation followed by deposition) within dry snow beneath the snow surface), freezing rain, solid precipitation in forms other than snow (re-sublimation composes 5-10% of the accumulation on Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica). -

![A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2754/a-report-on-the-guano-producing-birds-of-peru-informe-sobre-aves-guaneras-982754.webp)

A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 197 A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru [“Informe sobre Aves Guaneras”] July 2018* *Original manuscript completed1942 William Vogt1 with translation and notes by David Cameron Duffy2 1 Deceased Associate Director of the Division of Science and Education of the Office of the Coordinator in Inter-American Affairs. 2 Director, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Organization Contact Information: Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa 3190 Maile Way, St. John 408, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA Recommended Citation: Vogt, W. with translation and notes by D.C. Duffy. 2018. A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report 197. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany. Honolulu, HI. 198 pages. Key words: El Niño, Peruvian Anchoveta (Engraulis ringens), Guanay Cormorant (Phalacrocorax bougainvillii), Peruvian Booby (Sula variegate), Peruvian Pelican (Pelecanus thagus), upwelling, bird ecology behavior nesting and breeding Place key words: Peru Translated from the surviving Spanish text: Vogt, W. 1942. Informe elevado a la Compañia Administradora del Guano par el ornitólogo americano, Señor William Vogt, a la terminación del contracto de tres años que con autorización del Supremo Gobierno celebrara con la Compañia, con el fin de que llevara a cabo estudios relativos a la mejor forma de protección de las aves guaneras y aumento de la produción de las aves guaneras. -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Foundation Document Overview, Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Kenai Fjords National Park Alaska Contact Information For more information about the Kenai Fjords National Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (907) 422-0500 or write to: Superintendent, Kenai Fjords National Park, P.O. Box 1727, Seward, AK 99664 Significance and Purpose Fundamental Resources and Values Significance statements express why Kenai Fjords National Park resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. Fundamental resources and values are those features, systems, processes, experiences, stories, scenes, sounds, smells, or other attributes determined to merit primary consideration during planning and management processes because they are essential to achieving the purpose of the park and maintaining its significance. Icefields and Glaciers: Kenai Fjords National Park protects the Harding Icefield and its outflowing glaciers, where the maritime climate and mountainous topography result in the formation and persistence of glacier ice. The purpose of KENAI FJORDS NATIONAL PARK • Icefields is to preserve the scenic and environmental • Climate Processes integrity of an interconnected icefield, glacier, • Exit Glacier and coastal fjord ecosystem. • Science & Education Fjords: Kenai Fjords National Park protects wild and scenic fjords that open to the Gulf of Alaska where rich currents meet glacial outwash to sustain an abundance of marine life. -

Brief Communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of Ice from a Cirque Glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina

The Cryosphere, 13, 997–1004, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-997-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Brief communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of ice from a cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina Daniel Falaschi1,2, Andreas Kääb3, Frank Paul4, Takeo Tadono5, Juan Antonio Rivera2, and Luis Eduardo Lenzano1,2 1Departamento de Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 2Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 3Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, 0371, Norway 4Department of Geography, University of Zürich, Zürich, 8057, Switzerland 5Earth Observation research Center, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 2-1-1, Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8505, Japan Correspondence: Daniel Falaschi ([email protected]) Received: 14 September 2018 – Discussion started: 4 October 2018 Revised: 15 February 2019 – Accepted: 11 March 2019 – Published: 26 March 2019 Abstract. Among glacier instabilities, collapses of large der of up to several 105 m3, with extraordinary event vol- parts of low-angle glaciers are a striking, exceptional phe- umes of up to several 106 m3. Yet the detachment of large nomenon. So far, merely the 2002 collapse of Kolka Glacier portions of low-angle glaciers is a much less frequent pro- in the Caucasus Mountains and the 2016 twin detachments of cess and has so far only been documented in detail for the the Aru glaciers in western Tibet have been well documented. 130 × 106 m3 avalanche released from the Kolka Glacier in Here we report on the previously unnoticed collapse of an the Russian Caucasus in 2002 (Evans et al., 2009), and the unnamed cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina recent 68±2×106 and 83±2×106 m3 collapses of two ad- in March 2007.