Photoshop Typography: Elements of the Character Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Guide to UEB Reference Materials V.8.31.16

Supplementary Guide to UEB Reference Materials v.8.31.16 Unless otherwise indicated, page numbers refer to The Rules of Unified English Braille, 2013 For referenced BANA Guidances visit: www.brailleauthority.org * indicates definition of entry word A @ sign, 25 Caret, 24, 42 Abbreviations, 106, 152 Cent Sign ¢, 26 Accented letters, 42, 190 Chemistry, 89, 178, see BANA Guidance capitals, 80 Code switching, 199-210 in fully capped words, 89 how to use, 202-203 Acronyms, 106, 152 indicators Addition foreign language, 191-192, 195 non-technical materials, 31 IPA, 199, 207-208 technical materials, 169 music, 199, 208-209 Alphabetic wordsign, *7, 9, 15, 103-106, Nemeth code, 199, 209-210 164 non-UEB, 199, 203-208 Ampersand &, 21 Coinage, 26, 64 Anglicized words, 45, 158, 186, 189 Colored type, 11, 97 Apostrophe, 18, 69, 105, 107 Comma, 69 Arrows, 21, 174 numeric mode, 59 line mode, 219 Comparison, signs of, 169,31 Asterisk, 21 Compound words, bridging, 146 At sign @, 25 Computer material contractions in, 155 B email addresses, 155 Blank to be filled in, 73, 160 grade 1 indicators, 52 Boldface indicators, 91 Computer notation, 178 Brackets, opening and closing, 69, 78 Contracted (grade 2) braille, *7, 14 Braille grouping indicators, 23, 45, 172 usage cross-referenced, 14 Braille order, list of symbols, 275 Contractions summary, 9 Bullet, 24, 34, 37 Contractions, *7, 9, 103-168 abbreviations, 152 C acronyms, 152 Capitalization, 79-90 alphabetic wordsigns, *7, 9, 15, 103-106, grade 1, 55 164 indicators bridging, 146-152 choice of, 87 aspirated -

Word 2010 Basics I

Microsoft Word Fonts [email protected] Microsoft Word Fonts 1.0 hours Format Font ............................................................................................. 3 Font Dialog Box ........................................................................................ 4 Effects ................................................................................................ 4 Set as Default… .................................................................................. 4 Text Effects .............................................................................................. 5 Format Text Effects Pane ................................................................... 6 Typography .............................................................................................. 7 Advanced Font Features .......................................................................... 8 Drop Cap ................................................................................................. 8 Symbols .................................................................................................... 9 Class Exercise ......................................................................................... 10 Exercise 1: Simple Font Formatting ................................................. 10 Exercise 2: Advanced Options .......................................................... 12 Exercise 3: Text Effects, Symbols, Superscript, Subscript ................ 13 Exercise 4: More Formats ............................................................... -

Markup-Guide-For-Journal-Article-Pdfs.Pdf

UH Press Journals 1 1/21/2015 Marking PDFs Using Standard Adobe Reader Please read these instructions for marking digital proofs before you begin a project. Your Adobe software might appear somewhat differently on your monitor, depending on the version, so you may need to explore how to use it to obtain similar results as below. To access the needed features, click the “Comment” button at the upper right in the document window. Examples 1. Use the strikethrough tool for deletions (click the “T” icon with red strikethrough). If you simply want to delete text, no need to type “delete” in the comment box or on the PDF. The “strikethrough” icon in the comment box is enough to instruct the compositor. UH Press Journals 2 1/21/2015 2. When you use other tools, a pop-up dialog box appears. The text you enter in this box also appears in the Comments list to the right. Clicking on the comment box in the list will turn the selected comment yellow (or a pinkish color, depending on your monitor). The pop-up dialog box then opens to show the corresponding correction in the text. UH Press Journals 3 1/21/2015 3. If you highlight material, a Comment box will appear in the list of comments to the right. To add a note to the Comment box, double-click on the box to open and enter text. A fillable box appears for your note. To distinguish instructions from desired revisions, use angle brackets (</>), e.g., “<insert>X”. To delete a correction you made, right-click on the comment box or the correction itself to access options, then select “Delete.” UH Press Journals 4 1/21/2015 4. -

Paragraph Using the In-Line Style to Determine the Font-Size (15Pt) and Colour

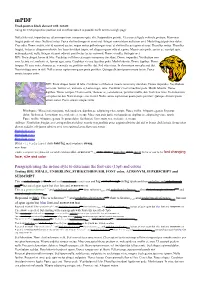

mPDF Fixed-position block element with Autofit Using the CSS properties position and overflow:auto it is possible to fit text to a single page: Nulla felis erat, imperdiet eu, ullamcorper non, nonummy quis, elit. Suspendisse potenti. Ut a eros at ligula vehicula pretium. Maecenas feugiat pede vel risus. Nulla et lectus. Fusce eleifend neque sit amet erat. Integer consectetuer nulla non orci. Morbi feugiat pulvinar dolor. Cras odio. Donec mattis, nisi id euismod auctor, neque metus pellentesque risus, at eleifend lacus sapien et risus. Phasellus metus. Phasellus feugiat, lectus ac aliquam molestie, leo lacus tincidunt turpis, vel aliquam quam odio et sapien. Mauris ante pede, auctor ac, suscipit quis, malesuada sed, nulla. Integer sit amet odio sit amet lectus luctus euismod. Donec et nulla. Sed quis orci. DIV: Proin aliquet lorem id felis. Curabitur vel libero at mauris nonummy tincidunt. Donec imperdiet. Vestibulum sem sem, lacinia vel, molestie et, laoreet eget, urna. Curabitur viverra faucibus pede. Morbi lobortis. Donec dapibus. Donec tempus. Ut arcu enim, rhoncus ac, venenatis eu, porttitor mollis, dui. Sed vitae risus. In elementum sem placerat dui. Nam tristique eros in nisl. Nulla cursus sapien non quam porta porttitor. Quisque dictum ipsum ornare tortor. Fusce ornare tempus enim. DIV: Proin aliquet lorem id felis. Curabitur vel libero at mauris nonummy tincidunt. Donec imperdiet. Vestibulum sem sem, lacinia vel, molestie et, laoreet eget, urna. Curabitur viverra faucibus pede. Morbi lobortis. Donec dapibus. Donec tempus. Ut arcu enim, rhoncus ac, venenatis eu, porttitor mollis, dui. Sed vitae risus. In elementum sem placerat dui. Nam tristique eros in nisl. -

Introduction to Microsoft Word 1

Introduction to Microsoft Word 1 Table of Contents Opening a New Document ......................................................................................................................... 3 Navigating the Toolbar .............................................................................................................................. 3 Clipboard ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cut ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Copy ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Paste ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Format Painter .................................................................................................................................... 4 Font ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 Changing font and text size .................................................................................................................. 5 Bold/Italicize/Underline text ............................................................................................................... -

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters Version 2.06, October 31, 2014 Pim Rietbroek Preamble Few typefaces – if any – allow the user to access every Latin character, every IPA character, every diacritic, and to have these combine in a typographically satisfactory manner, in a range of styles (roman, italic, and more); even fewer add full support for Greek, both modern and ancient, with specialised characters that papyrologists and epigraphers need; not to mention coverage of the Slavic languages in the Cyrillic range. The Brill typeface aims to do just that, and to be a tool for all scholars in the humanities; for Brill’s authors and editors; for Brill’s staff and service providers; and finally, for anyone in need of this tool, as long as it is not used for any commercial gain.* There are several fonts in different styles, each of which has the same set of characters as all the others. The Unicode Standard is rigorously adhered to: there is no dependence on the Private Use Area (PUA), as it happens frequently in other fonts with regard to characters carrying rare diacritics or combinations of diacritics. Instead, all alphabetic characters can carry any diacritic or combination of diacritics, even stacked, with automatic correct positioning. This is made possible by the inclusion of all of Unicode’s combining characters and by the application of extensive OpenType Glyph Positioning programming. Credits The Brill fonts are an original design by John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks. Alice Savoie contributed to Brill bold and bold italic. The black-letter (‘Fraktur’) range of characters was made by Karsten Lücke. -

Perfecting Your Hotdocs Templates in Microsoft Word

2009 Practice Management Annual Conference Perfecting Your HotDocs Templates in Microsoft Word Barron K. Henley, Esq. HMU Consulting, Inc. [email protected] 2009 Practice Management Annual Conference Rea lities o f MS Wor d • Word is complicated • Most users have no idea how it works • YtYour templ lthldates should compensa tfte for user ignorance 2009 Practice Management Annual Conference Word’ s Forma tting T ypes • FONT: Font name, style (regular, italic, bold, bold italic), size (measured in points), color, underline style, character spacing, effects (strikethrough, double strikethrough, superscript, subscript, shadow, outline, emboss, engrave, small caps, all caps, hidden) & case • PARAGRAPH: Indents and spacing (alignment, outline level, indentation, spacing); line and page breaks including widow/orphan control, keep lines together , keep with next & hyphenation; tabs; borders and bullets and paragraph numbering • SECTION: ClColumns, marg ins, paper s ize, or ien ttitation (por tra it or landscape), paper source (set which paper tray your printer pulls from), line numbering, & headers and footers (includes page numbering) 2009 Practice Management Annual Conference Styl es •A style is a set of formatting characteristics that you can apply to text, tables, and lists in your document to quickly change their appearance (fix them) • Styles control font and paragraph formatting • It is the most important feature in Word 2009 Practice Management Annual Conference WdBtPtiWord Best Practices • You should be using Word 2007 – Better -

Text Box Editor

Text Box Editor The Text Box Editor presents controls for entering and formatting text, equations, and multimedia files. When it is enabled, it appears throughout the system as the default editor when adding text through a text box. The Text Box Editor has three collapsible rows of buttons. The lists below define the functions of each button. First Row: Basic Actions 1. Bold: Bold the selected text. 2. Italicize: Italicize the selected text. 3. Underline: Underline the selected text. 4. Strikethrough: Display the text with a horizontal line through the letters. Note: Strikethrough font style is not supported by all browsers. 5. Select a paragraph style for the text. Click the down arrow next to the displayed current style to select from a list of available styles. Instructional Technology Services | Blackboard Faculty Tutorials Page 1 6. Select the font face for the text. Click the down arrow next to the displayed current font to select from a list of all available fonts. 7. Select the size of the text. Click the down arrow next to the displayed current font size to select from a list of all available font sizes. 8. Create a bulleted list. 9. Create a numbered list. 10. Set the text color. Click the down arrow to select a different text color. 11. Set the text highlight (background) color. Click the down arrow to select a different highlight color. 12. Remove all formatting, leaving only the plain text. 13. Open a preview window showing how the content will appear after submitting. 14. Open the context editor help window. -

Formatting Text

Class VII Subject: Computer Science Textbook: IT Planet Petabyte Chapter – 8: HTML – Creating Web Page General Instructions: 1. Read the text thoroughly. 2. Exercise to be done in the book. 3. YouTube links are given at the end of the notes for further clarification of the usage of tags. Formatting Text Bold, Italic and Underline Text Strike, Subscript, Superscript and Typewriter Style Text Changing the Alignment of Heading Changing the Paragraph Alignment Changing Font of Text Changing the Size of Font Changing the Color of Text Changing the Color of a Part of Text Changing Background Color of the Page HTML Formatting HTML Formatting is a process of formatting text for a better look and feel. There are many formatting tags in HTML. In HTML the formatting tags are divided into two categories: Physical style tags: These tags specify a particular font change that is interpreted strictly by all browsers. Logical style tags: These tags allow a browser to interpret the tag based on browser settings, relative to other text on a web page. Making text Bold: We can make the text bold using the <b> tag. The tag uses both opening and closing tags. The text that needs to be made bold must be within <b> and </b> tags. Making text Italic: The <i> tag is used to italicise the text. It opens with <i> and ends with </i> tag. Underlined Text Anything that appears within <u>...</u> element, is displayed with an underline. Strike Text Anything that appears within <strike>...</strike> element is displayed with a strikethrough, which is a thin line through the text. -

MOAC 2013 Lesson 3

3 Character Formatting LESSON SKILL MATRIX Skill Exam Objective Objective Number Formatting Characters Manually Change font attributes. 2.2.1 Using the Format Painter Demonstrate how to use Format Painter. 2.2.3 Highlight text selections. 2.2.8 Formatting Text with Styles Add styles to text. 2.2.9 Modify existing style attributes. 2.2.11 Formatting Text with WordArt Import Files. 1.1.3 Change text to WordArt. 2.2.10 OOpOpenen nnon-nativeono -natiive fi les directly in WordWord.. 11.1.4.1.4 OpOpenen a PPDFDFD iinn WWoWordrdr fforor eediting.did ting. 11.1.5.1..5 Removing Text Formatting ClCleareaar exexistingistiing forformatting.mmattting. 2.2.62.2 2.6 KEY TERMS • character • character styles • font • live preview • monospaced • paragraph styles • point size • proportional space • sans serif • serif • Text Effects • WordArt 68 © bowdenimages/iStockphoto Character Formatting 69 With more than 20 million members and 2,600 facilities, the YMCA (“the Y”) is the largest community service organization in the United States. Health and fi tness programs offered at the Y include group exercises for adults and youth, family time, sports and recreation, and group interests for senior citizens. The staff and volunteers at the Y need to create various types of doc- uments for announcing and advertising programs throughout the year and for organizing and registering members for participation in these programs. Microsoft Word is a great tool for creating professional-looking documents © bowdenimages/iStockphoto that will capture attention. In this lesson, you learn how to use character formatting to create professional-looking documents. SOFTWARE ORIENTATION The Font Group As you learneaarn to fformatormam t tetext,xxt, it is imimportantmportant to bbecomeecome fafamiliarmim liarr wwith the Font group of commands.ds. -

MICROSOFT POWERPOINT MADE EASY - Version 3

POWER-TECH COMPUTERS (PTC), Revised on 22nd November 2020, MICROSOFT POWERPOINT MADE EASY - Version 3 MICROSFT POwerPoinT (MSPP) (BASED ON OFFICE 365 AND WINDOWS 10) Module 4 FORMATTING TEXT AND LAYOUTS Fredrick Ezeh Power-Tech Computers (PTC) © Copyright 2020 THERE IS NO REAL SUCCESS WITHOUT SINCERE HARDWORK) - FRED 1 POWER-TECH COMPUTERS (PTC), Revised on 22nd November 2020, MICROSOFT POWERPOINT MADE EASY - Version 3 MICROSOFT POWERPOINT@ MODULE 4 FORMATTING TEXT AND LAYOUTS ➢ Font-Level Formatting ➢ Aligning Text ➢ Using Indentations ➢ Using Line and Paragraph Spacing ➢ Creating and Working with Columns ➢ Using Format Painter ➢ Changing Case of Text ➢ Using Superscripts and Subscripts ➢ Using Single and Double-Strikethrough (Naira Sign) ➢ Adding Bullets and Numbered Lists ➢ Creating Headers and Footers ➢ Inserting Slide Numbers ➢ Insert Date and Time Font-Level Formatting A font is a set of characters that has a unique style such as the Courier New font, New Roman Times etc. Font-size refers to the text size and is generally measured in points. Font-style refers to text enhancements such as bold, italics etc. Other attributes can be underline, shadow, emboss etc. To apply all the mentioned font-level formatting to text: 1. Select the text 2. Click Home menu/tab. From the Font group , click the icon to display a dialog box 3. Click the “Font” tab 4. Select the Font type from the “Latin text font” box e.g. Arial, Calibri etc. 5. Select the Font-Style e.g. bold, italics etc. 6. Select the Font-Size, and Select the Font-Color 7. Select the Underline-Style and Color, and other effects like Shadow, Strikethrough etc. -

3-1 3-1 Introduction the Aviation Forecasts Provide Estimates For

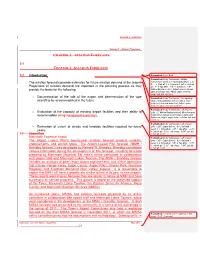

CHAPTER 2 - INVENTORY CHAPTER 3 – AVIATION FORECASTS CHAPTER 3. AVIATION FORECASTS 3-1 CHAPTER 3. AVIATION FORECASTS 3-1 Introduction Formatted: Font: Bold Formatted: Body Text Indent, Outline The aviation forecasts provide estimates for future aviation demand at the airport. numbered + Level: 2 + Numbering Style: 1, 2, 3, … + Start at: 1 + Alignment: Left + Aligned Projections of aviation demand are important in the planning process as they at: 0" + Tab after: 0.5" + Indent at: 0.5", provide the basis for the following: Widow/Orphan control, Adjust space between Latin and Asian text, Adjust space between Asian text and numbers • Documentation of the role of the airport and determination of the type Formatted: Body Text Indent, Line spacing: aircraft to be accommodated in the future. single, Widow/Orphan control, Adjust space between Latin and Asian text, Adjust space between Asian text and numbers Formatted: Body Text Indent, Left, Indent: • Evaluation of the capacity of existing airport facilities and their ability to Left: 0", Widow/Orphan control, Allow hanging accommodate designsproposed expansion. punctuation, Adjust space between Latin and Asian text, Adjust space between Asian text and numbers Formatted: Body Text Indent, Left, Indent: • Estimation of extent of airside and landside facilities required for future Left: 0.69", Space Before: 6 pt, Bulleted + Level: 1 + Aligned at: 0.5" + Tab after: 0.75" years. + Indent at: 0.75", Tab stops: 0.94", List tab 3-2 Airport Role + Not at 0.75" Mammoth Yosemite Airport Formatted: Body Text Indent, Left, Indent: The Airport Layout Plan’s twenty-year aviation forecast projects markets, Left: 0.69", Space Before: 6 pt, Bulleted + enplanements, and aircraft types.