First Thoughts--Herodotus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-800-495-0119 | [email protected] | Teneohg.Com ALASKA ARIZONA

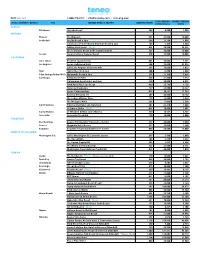

DATE: May 2016 1-800-495-0119 | [email protected] | teneohg.com TOTAL MEETING LARGEST MEETING STATE / COUNTRY / DISTRICT CITY MEMBER HOTELS & RESORTS SLEEPING ROOMS SPACE (Indoor) SPACE ALASKA Girdwood Alyeska Resort 304 8,000 3,000 ARIZONA Phoenix The Wigwam 331 45,000 10,800 Scottsdale FireSky Resort & Spa 204 13,924 6,800 Sanctuary on Camelback Mountain Resort & Spa 105 6,200 3,204 Talking Stick Resort (New) 496 50,000 24,556 The Scottsdale Resort at McCormick Ranch 326 50,000 10,000 Tucson Loews Ventana Canyon Resort 398 35,000 10,800 CALIFORNIA Lake Tahoe Resort at Squaw Creek 405 33,000 9,525 Los Angeles Loews Hollywood Hotel 628 76,000 25,090 Sofitel Los Angeles at Beverly Hills 295 10,000 3,823 Ojai Ojai Valley Inn & Spa 308 16,000 6,000 Palm Springs/Indian Wells Miramonte Resort & Spa 215 16,190 5,824 San Diego Bahia Resort Hotel 313 21,000 7,992 Catamaran Resort Hotel and Spa 310 20,000 4,876 Hard Rock Hotel San Diego 420 27,790 9,170 Hotel del Coronado 757 65,000 12,567 Loews Coronado Bay 439 24,691 13,764 Rancho Bernardo Inn 287 40,000 10,140 The Lodge at Torrey Pines 170 13,000 3,250 The Westgate Hotel 223 17,000 2,500 San Francisco Park Central Hotel San Francisco 681 23,210 9,040 Sir Francis Drake (New) 416 18,000 3,081 Santa Monica Le Méridien Delfina Santa Monica 310 10,937 4,533 Temecula Temecula Creek Inn 130 10,000 4,000 COLORADO Breckenridge Beaver Run Resort & Conference Center 515 40,000 7,200 Denver Magnolia Hotel Denver 297 10,000 3,500 Keystone Keystone Resort and Conference Center 850 60,000 19,800 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Washington D.C. -

What Do We Recommend?

While travelling, we like feeling the city, wake up early with the sun rise, visit all the cultural and historical places and taste the city’s special flavors. According to that concept, we preapared the “Eat, Love, Pray in Istanbul Guide” which is all about our suggestions with little tips. We hope you could benefit from the hand book. Have a good stay and enjoy the city. Ramada Istanbul Grand Bazaar Family SOPHIA PITA RESTAURANT &TAPAS Offers a fusion of authentic and modern Spanish tapas accompanied by a distinguished selection of Turkish wines and selected international wines and liqours, also open for breakfast and dinner with a relaxing atmosphere at the Aya Sofya’s backyard. Adress;Boutique St. Sophia Alemdar Cad. No.2 34122 Sultanahmet / Istanbul Phone;009 0212 528 09 73-74 PS:How to get there;The nearest tram station is Sultanahmet or Gulhane tram station. BALIKÇI SABAHATTİN “Balıkçı Sabahattin” ( Fisherman Sabahattin) was at first running a traditional restaurant left by his father some streets behind which not everyone knew but those who knew could not give up, before he moved to this 1927 made building restored by Armada... Sabahattin, got two times the cover subject of The New York Times in the first three months in the year 2000… Sabahattin, originally from Trilye (Mudanya, Zeytinbag), of a family which knows the sea, fish and the respect of fish very well, know continues to host his guest in summer as in winter in this wooden house...His sons are helping him... In summer some of the tables overflow the street. -

Golden Eagle Luxury Trains

golden eagle luxury trains central europe & transylvania golden eagle danube express central europe & transylvania prague - istanbul (eastbound) istanbul - prague (westbound) czech republic - poland - slovakia - austria - hungary romania - bulgaria - turkey Charles Bridge, Prague Maiden Tower, Istanbul Festetics Palace, Keszthely Combining the romance of historic medieval settlements with the architectural splendour of some of Europe’s most beautiful cities, this exclusive rail cruise through the diverse and dramatic landscapes of Southern Europe, promises to be truly unforgettable. Traversing over 3,000km, across eight countries, this 14-day voyage offers the ultimate European adventure. Relax in the elegant surroundings onboard the Golden Eagle Danube Express and admire the ever-changing landscapes of Central and Southern Europe as we glide between these charming European cities. Marvelling at the beauty of Prague and Istanbul, at either end of our journey, we explore the contrasting cultures and architectural masterpieces that have been shaped by centuries of ancient civilisations. Take advantage of our flexibleFreedom of Choice touring programme here to truly personalise your experience in these magical destinations. As we cruise through the scenic heart of Transylvania and the diverse landscapes of its neighbouring countries, we take time to unearth some of the hidden treasures of this captivating part of the world. With the medieval cities of Romania combined with the imperial beauty of Vienna and the rich, poignant history of Kraków -

Rejuvenating at the Pera Palace Istanbul by Inka Piegas-Quischote

Travel Rejuvenating at the Pera Palace Istanbul By Inka Piegas-Quischote Timeless decadence displayed in the Kubbeli Ceilings alk about the royal Along came the Pera Palace. Orient Express was written in her a chauffeured limousine and upon neither in the suite nor in the skylights all will do this to you. You can either swim in the pool, keep conveniently. Just a few steps from treatment! If you plan to The art deco marvel opened its favorite room: number 411. A bit the arrival, the doorman will step out, the bathroom. During refurbishment, a treasure fit in the state of the art gym or Taksim Square, I took the metro to visit Istanbul and have a few doors in 1892 and featured the first worse for wear, the hotel closed for open your door and greet you by trove of Christoffl silver was have a Turkish bath and massage in the historical district of bucks to spare, there is no electrically operated elevator in a while to undergo extensive name even if you have never been a After unpacking, I went downstairs discovered hidden away in the cellar, the hamam. Beauty products used Sultanahmed, where all the famous better place to stay than the Turkey, as well as hot and cold renovation, which lasted a few years. guest before. It´s simply a nice touch to the famous Orient Bar, where which is now polished and used in are specially made for the Pera sites like Hagia Sophia, Blue Mosque, Temblematic Pera Palace Hotel. You running water. It was also the venue In September 2010, it opened its and makes you feel welcome. -

Circumnavigation of the Black Sea

CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF THE BLACK SEA June 26 - July 10, 2020 | 15 Days | Aboard Le Bougainville UKRAINE Expedition Highlights Odessa • Choose from several tours highlighting Istanbul’s wealth of historic sites and ROMANIA RUSSIA Histria architectural treasures. Constanta DANUBE RIVER DELTA Sochi • Enjoy an energetic performance of Varna BLACK SEA traditional dances in Georgia while BULGARIA sampling local wines. GEORGIA • Explore the grand city of Odessa, with Bartin Batumi BOSPORUS splendid examples of elegant 18th- and Istanbul Safranbolu Samsun Trabzon 19th-century architecture, including a Amasya Sumela tour of the magnificent Opera House. TURKEY • Cruise through the winding canals of the Danube River Delta, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve, as we search for over 200 species of birds. • Wander through a wealth of well- preserved Ottoman architecture in Safranbolu. • Itinerary .................................... page 2 > • Flight Information ...................... page 3 > • Ship, Deck Plan & Rates ............ page 4 > • Featured Leaders ....................... page 5 > • Know Before You Go ................. page 5 > © Allan Langdale © Allan Langdale • Optional Pre-Voyage Extension .. page 6 > BLUE MOSQUE SUMELA MONASTERY © Allan Langdale © Allan Langdale Wednesday, July 1 Itinerary SAMSUN / AMASYA From the port of Samsun, drive inland to Amasya, former capital of the kingdom of Pontus during the third century BC. Explore the Based on the expeditionary nature of our trips, there may be photogenic alleys lined with 19th-century Ottoman-era houses, ongoing enhancements to this itinerary. the ethnographic museum, and an Islamic seminary. Enjoy lunch overlooking the town and Pontic Tombs. Friday, June 26, 2020 DEPART USA Thursday, July 2 Board your overnight flight to Istanbul. TRABZON / SUMELA Ancient Greeks settled in Trabzon along a branch of the Silk Road from Asia. -

Master Documents List 7 9.Xlsx

DATE: July 2015 DOMESTIC HOTELS & RESORTS ROOMS DOMESTIC HOTELS & RESORTS ROOMS ALASKA Naples LaPlaya Beach & Golf Resort 189 Girdwood Alyeska Resort 304 Naples Naples Grande Beach Resort 474 Orlando Buena Vista Suites 279 ARIZONA Orlando Caribe Royale All-Suite Hotel & Convention Center 1,338 Chandler Sheraton Wild Horse Pass Resort & Spa 500 Orlando Hard Rock Hotel at Universal Resort 650 Phoenix The Wigwam 331 Orlando Loews Portofino Bay Hotel 750 Scottsdale Firesky Resort & Spa 204 Orlando Loews Royal Pacific Resort 1,000 Scottsdale Sanctuary on Camelback Mountain Resort & Spa 105 Orlando Loews Sapphire Falls Resort *(Opens Summer 2016) 1,000 Scottsdale The Scottsdale Resort at McCormick Ranch 326 Orlando Rosen Centre Hotel 1,334 Tucson Loews Ventana Canyon Resort 398 Orlando Rosen Plaza Hotel 800 Orlando Rosen Shingle Creek 1,501 CALIFORNIA Orlando Universal's Cabana Bay Beach Resort 1,800 DMC Member: Bixel & Company Palm Beach Eau Palm Beach Resort & Spa 309 Lake Tahoe Resort at Squaw Creek 405 Palm Beach Tideline Ocean Resort & Spa 134 Los Angeles Loews Hollywood Hotel 628 Palm Beach Gardens PGA National Resort & Spa 359 Los Angeles Sofitel Los Angeles at Beverly Hills 295 St Pete Beach Loews Don CeSar Hotel 277 Ojai Ojai Valley Inn & Spa 308 Tampa Saddlebrook Resort *(800 Bedrooms) 540 Palm Springs Miramonte Resort & Spa (New Member) 215 Palm Springs Riviera Palm Springs 398 GEORGIA San Diego Bahia Resort Hotel 313 Atlanta The InterContinental Buckhead, Atlanta 422 San Diego Catamaran Resort Hotel and Spa 310 San Diego Hard Rock Hotel San Diego 420 IDAHO San Diego Hotel del Coronado 757 Coeur d'Alene The Coeur d'Alene Resort 338 San Diego Loews Coronado Bay 439 Sun Valley Sun Valley Resort 485 San Diego Rancho Bernardo Inn 287 San Diego The Lodge at Torrey Pines 170 ILLINOIS San Diego The Westgate Hotel 223 DMC Member: Chicago Travel Consultants, Inc. -

Read Book Wallpaper* City Guide Istanbul Ebook

WALLPAPER* CITY GUIDE ISTANBUL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gökhan Karakus | 128 pages | 25 Sep 2014 | Phaidon Press Ltd | 9780714868301 | English | London, United Kingdom Wallpaper* City Guide Istanbul PDF Book In stock Usually dispatched within 24 hours. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. This item doesn't belong on this page. Google Books — Loading This item can be requested from the shops shown below. Erdogan Rising. Get the latest articles and exclusive discounts delivered straight to your inbox. Here is a precise, informative, insider's checklist of all you need to know about the world's most intoxicating cities. Editions: , X. View Hotel. Following the initial email, you will be contacted by the shop to confirm that your item is available for collection. Pera Palace Hotel. Hannah Lucinda Smith. Unfortunately there has been a problem with your order. If this item isn't available to be reserved nearby, add the item to your basket instead and select 'Deliver to my local shop' at the checkout, to be able to collect it from there at a later date. DK Eyewitness Top 10 Istanbul. All forums. In short, these guides act as a passport to the best the world has to offer. Original publication date. CD Audiobook 0 editions. Buy the guides! Quick Links Amazon. Your order is now being processed and we have sent a confirmation email to you at. Haiku summary. You may also like. Preferred contact method Email Text message. We hope you'll join the conversation by posting to an open topic or starting a new one. -

Eastern Tales of Turkey

EASTERN TALES OF TURKEY ISTANBUL, URFA, ADANA, CAPPADOCIA, & ANKARA KER & DOWNEY | 6703 HIGHWAY BLVD | KATY, TX 77494 | PHONE: 281.371.2500 | FAX: 281.371.2514 | RESERVATIONS: 800.423.4236 KER & DOWNEY // EASTERN TALES OF TURKEY SUGGESTED ITINERARY AT A GLANCE DAY: ITINERARY: ACCOMMODATION: MEALS: DAY 1 ISTANBUL PERA PALACE HOTEL DAY 2 URFA MANICI HOTEL B DAY 3 ADANA ADANA HILTON HOTEL B,L DAY 4 CAPPADOCIA MUSEUM HOTEL B DAY 5 CAPPADOCIA MUSEUM HOTEL B DAY 6 CAPPADOCIA DEDEMAN HOTEL B DAY 7 ANKARA DIVAN HOTEL B DAY 8 ANKARA DIVAN HOTEL B DAY 9 ISTANBUL PERA PALACE HOTEL B DAY 10 DEPARTURE B KER & DOWNEY // EASTERN TALES OF TURKEY HISTORIC, EXPERIENTIAL TURKEY DAY 1 - DAY 2 URFA DISCOVER THE ANCIENT TALES OF URFA. After spending the first night in Istanbul, head to the ancient city of Urfa in southeastern Turkey. Here guests encounter one of the most startling archaeological discoveries of our time: Gobekli Tepe. Consisting of massive carved stones about 11,000 years old, crafted and arranged by prehistoric people who had not yet developed metal tools or even pottery, Turkey’s stunning Gobekli Tepe upends the conventional view of the rise of civilization. Continue to Harran, a city that seems to be as old as the Bible, if not older. The most distinctive aspect of Harran is its mud beehive houses, and when accompanied by the Balikligol is believed to be the place owner you may tour inside one of these unconventional homes. where Abraham was born, in a cave, and this area is considered sacred by Return to Urfa and visit the legendary Balikligol, translated to “fish pool,” a great piece followers of Judaism, Christianity of architecture and Turkey’s closest equivalent to the Taj Mahal. -

Queer Desires of Extravagant Strangers in Sinan Ünel's Pera Palas

“Built for Europeans who came on the Orient Express”: Queer Desires of Extravagant Strangers in Sinan Ünel’s Pera Palas Ralph J. Poole ABSTRACT The Pera Palace Hotel has long been a site of transnational interest. Its original intent when it was built in 1892 was to host passengers of the Orient Express, and its nickname as the “oldest European hotel of Turkey” aptly reflects this heritage. It has been the setting of Anglophone world literature, such as Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” Graham Greene’s Travels With My Aunt, and, perhaps most famously, Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. But the hotel also reflects Turkey’s own turbulent history from Istanbul’s luxurious Belle Epoque to the oftentimes nostalgic luxury of a postmodern metropolis, with Room 101 being converted into a memorial for Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, thus designating the space as museum-hotel. Pera Palas (1998), the play by Turkish-American playwright Sinan Ünel, is a complex spatio-temporal interlacing of the hotel’s/nation’s history with that of a Turk- ish family and their Anglo-American friends and lovers encompassing the 1920s via the 1950s to present time. Intermingling East and West, past and present, Islam and Christianity, traditional- ists and feminists, hetero- and homosexuality, this play is at once a multifarious love story and a polyloguous diasporic tale. “a fucking palace:” Grand Hotel When Agatha Christie visited the Pera Palace Hotel in Istanbul in the mid- 1930s and allegedly began to write one of her most famous crime novels, Murder on the Orient Express (1934), the prime time of grand hotels was already over (Karr 118). -

Pera Palace Hotel Construction Technology

ARTICLE MEGARON 2019;14(1):11-17 DOI: 10.5505/MEGARON.2018.35493 Pera Palace Hotel Construction Technology Pera Palas Oteli Yapım Teknolojisi Banu ÇELEBİOĞLU, Uzay YERGÜN ABSTRACT From the first quarter of the 18th century, a new perspective for European civilization was adopted by the Ottoman Empire and this West- ernization concept was transformed into an essential revolutionary movement in governmental and social structure. Therefore, the initials steps of implementing any change were taken with the decision of constructing the buildings with new functions that are required as the necessary structures of modern state and public, according to European architectural design models with modern building materials and construction technologies. Building materials fabricated by European industry, such as brick, steel and concrete, as well as construction technologies like brick arch, steel-frame and concrete were important determinants in the historical evolution of Ottoman architecture after the first quarter of the 19th century. One of the first structures built with the new function and construction technology of Ottoman architecture is Pera Palace Hotel (1895) designed by famous architect of this period, Alexander Vallaury. Apart from the Ottoman palaces, it’s a building that the first electricity is supplied, the first elevator is located and the first hot water is active. In this paper, the architectural characteristics of the first modern hotel structure built in the Pera region, the construction system vertically supported by prefabricated bricks and arched floor with steel beams will be carried out in the frame of the original architectural projects. The significance of the build- ing will be revealed in terms of cultural values of the Ottoman architecture. -

The Ottoman Imperial Hotels Company

Tourism Management 51 (2015) 103e111 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tourism Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tourman _ The Ottoman Empire's first attempt to establish hotels in Istanbul: The Ottoman Imperial Hotels Company * Aytug Arslan a, , Hasan Ali Polat b a _ _ Tourism Guidance/Tourism Faculty, Izmir Katip Çelebi University, Izmir 35620, Turkey b Beys¸ehir Ali Akkanat Vocational High School, Selçuk University, Konya 42700, Turkey highlights _ 19th century Istanbul lacked facilities for its influx of European visitors. The Sultan granted James Masserie a charter to establish a company to build hotels. Despite several attempts, The Ottoman Imperial Hotels Company was unsuccessful. Examines the archival company charter, travel guides, and public letters. Despite reforms, Eastern capital focused on profit from government business. article info abstract _ Article history: The number of travellers from Europe to Turkey, and especially Istanbul, increased dramatically as travel Received 12 July 2014 conditions improved pursuant to the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. However, the capital city Accepted 10 May 2015 of the Ottoman Empire was not equipped with adequate accommodations to host these visitors. Available online 29 May 2015 Therefore, they had to take some measures to deal with this problem. This study gives an account of the Ottoman Imperial Court's first attempt to establish modern hotels to meet the needs to accommodate the _ Keywords: growing number of visitors to Istanbul. This study provides the first examination of the imperial edict Regulation authorizing the establishment of the Ottoman Imperial Hotel Company and the construction of a hotel, the Hotel Company earliest documents related to this issue. -

[email protected]

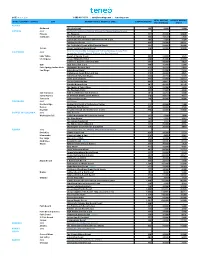

DATE: March 2016 1-800-495-0119 | [email protected] | teneohg.com TOTAL MEETING LARGEST MEETING STATE / COUNTRY / DISTRICT CITY MEMBER HOTELS, RESORTS & DMCs SLEEPING ROOMS SPACE (Indoor) SPACE ALASKA Girdwood Alyeska Resort 304 8,000 3,000 ARIZONA DMC Southwest Conference Planners (Phoenix/Scottsdale/Sedona/Tucson) Phoenix The Wigwam 331 45,000 10,800 Scottsdale FireSky Resort & Spa 204 13,924 6,800 Sanctuary on Camelback Mountain Resort & Spa 105 6,200 3,204 Talking Stick Resort (New) 496 50,000 24,556 The Scottsdale Resort at McCormick Ranch 326 50,000 10,000 Tucson Loews Ventana Canyon Resort 398 35,000 10,800 Bixel & Company (LA), Arrangements Unlimited (Orange County/Palm CALIFORNIA DMC Springs/San Diego), Cappa & Graham, Inc. (San Francisco) Lake Tahoe Resort at Squaw Creek 405 33,000 9,525 Los Angeles Loews Hollywood Hotel 628 76,000 25,090 Sofitel Los Angeles at Beverly Hills 295 10,000 3,823 Ojai Ojai Valley Inn & Spa 308 16,000 6,000 Palm Springs/Indian Wells Miramonte Resort & Spa 215 16,190 5,824 San Diego Bahia Resort Hotel 313 21,000 7,992 Catamaran Resort Hotel and Spa 310 20,000 4,876 Hard Rock Hotel San Diego 420 27,790 9,170 Hotel del Coronado 757 65,000 12,567 Loews Coronado Bay 439 24,691 13,764 Rancho Bernardo Inn 287 40,000 10,140 The Lodge at Torrey Pines 170 13,000 3,250 The Westgate Hotel 223 17,000 2,500 San Francisco Park Central Hotel San Francisco 681 23,210 9,040 Santa Monica Le Méridien Delfina Santa Monica 310 10,937 4,533 Temecula Temecula Creek Inn 130 10,000 4,000 COLORADO DMC AXS Group Breckenridge Beaver Run Resort & Conference Center 515 40,000 7,200 Denver Magnolia Hotel Denver 297 10,000 3,500 Keystone Keystone Resort and Conference Center 850 60,000 19,800 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DMC DMC Network Washington D.C.