Environmental and Behavioural Factors Associated with Mycobacterium Ulcerans Infection in the District of Lalo in Benin: a Case-Control Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. General Information

Reference: 2011/00520/FR/01/01 03/05/2013 EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR HUMANITARIAN AID AND CIVIL PROTECTION – ECHO SINGLE FORM FOR FINAL REPORT 1. GENERAL INFORMATION UNDP-USA 1.2 Title of the Action Strengthening local capacities for response and management of risks with respect to seismic events in the Provinces of Puerto Plata and Santiago, Dominican Republic. 1.3 Area of intervention (country, region, localities) World Area Countries Region America DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Cibao Region: Puerto Plata y Santiago Provinces 1.4 Start date of the Action Start date 01/07/2011 If the Action has already started explain the reason that justifies this situation (urgent Action or other reason) NA 1.5 Duration of the Action in months 18 0 months days 1.6 Start date for eligibility of expenditure Is the start date for eligibility of expenditure equal to the date of submission of the initial proposal? No If yes, explain expenses charged to the budget between date of initial proposal submission and start date of the action If no, enter the start date for eligibility and explain 01/07/2011 NA 1.7 Requested funding modalities for this agreement Multi-donor action In case of 100% financing, justify the request 1.8 Urgent action No If Yes: In case of urgent action in the framework of another ECHO decision, Please justify 1.9 Control mechanism to be applied P 1.10 Proposal and reports Submission date of the initial proposal 15/04/2011 Purpose of this submission FINAL REPORT Agreement number: ECHO/DIP/BUD/2011/92008 page 1/69 Reference: 2011/00520/FR/01/01 -

The Business Response to Remedying Human Rights Infringements: the Current and Future State of Corporate Remedy

The business response to remedying human rights infringements: The current and future state of corporate remedy Human Rights Remedy | June 2018 Australian Business Pledge against Forced Labour i Table of contents 1. Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 About this Report .................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. Context ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 The Remedy Challenge ........................................................................................................................................ 3 4. Existing frameworks and guidance on the provision of remedy ................................................................................... 4 4.1 International Frameworks and Guidance ............................................................................................................. 5 5. Legal Context .............................................................................................................................................................. -

PARTNERING for DIAGNOSTIC EXCELLENCE ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Our Vision a World Where Diagnosis Guides the Way to Health for All People

PARTNERING FOR DIAGNOSTIC EXCELLENCE ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Our vision A world where diagnosis guides the way to health for all people Our mission Turning complex diagnostic challenges into simple solutions to overcome diseases of poverty and transform lives CONTENTS Leadership Message 4 2017 in Numbers 5 Key Achievements in Country Offices 6 Taking Stock: Mid-Term Strategy Review 9 Taking Action Catalyse Development 10 Guide Use & Inform Policy 12 Accelerate Access 13 Shape the Agenda 15 Spotlight on Diseases Fever, AMR & Outbreaks 16 Hepatitis C 18 Malaria 19 Neglected Tropical Diseases 21 Tuberculosis 22 Governance 23 2017 Financial Statements 26 LEADERSHIP MESSAGE Dr Catharina Boehme Mark Kessel Chief Executive Officer Chair of the Board The year 2017 marks the halfway point in diagnostic tests are quality assured. the delivery of our 2015–2020 strategy. We continue to contribute to global We are on track, as confirmed by an research: this year we published external mid-term review, and we enter 65 peer-reviewed manuscripts, and the second half of this strategic period collaborated with WHO to develop with renewed energy and concrete plans target product profiles for new tests, as for further portfolio strengthening. well as in-depth landscape reports and market analyses of diagnostic products. In the past year, more than 15 million For TB, we provided data to support FIND-supported products were provided the WHO recommendation of the Xpert to simplify diagnosis in low- and middle- MTB/RIF Ultra assay, which will advance income countries. We added 9 in vitro TB diagnostic capabilities in difficult-to- diagnostic projects to our portfolio, diagnose populations, such as children bringing the total in development to 48. -

Integrated Control and Management of Neglected Tropical Skin Diseases

POLICY PLATFORM Integrated Control and Management of Neglected Tropical Skin Diseases Oriol Mitjà1,2*, Michael Marks3,4, Laia Bertran1, Karsor Kollie5, Daniel Argaw6, Ahmed H. Fahal7, Christopher Fitzpatrick6, L. Claire Fuller8, Bernardo Garcia Izquierdo9, Roderick Hay8, Norihisa Ishii10, Christian Johnson11, Jeffrey V. Lazarus1, Anthony Meka12, Michele Murdoch13, Sally-Ann Ohene14, Pam Small15, Andrew Steer16, Earnest N. Tabah17, Alexandre Tiendrebeogo18, Lance Waller19, Rie Yotsu20, Stephen L. Walker3, Kingsley Asiedu6 1 Skin NTDs Program, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, Hospital Clinic-University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2 Division of Public Health, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Papua New Guinea, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 3 Clinical Research Department, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom, 4 Hospital for Tropical Diseases, University College London Hospitals NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom, 5 Neglected Tropical and Non Communicable Diseases Program, Ministry of Health, Government of Liberia, Liberia, 6 Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, a1111111111 7 The Mycetoma Research Centre, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan, 8 International Foundation for a1111111111 Dermatology, London, United Kingdom, 9 Anesvad foundation, Bilbao, Spain, 10 Leprosy Research Center, a1111111111 National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan, 11 Fondation Raoul -

Health of Men, Women, and Children in Post-Trafficking Services In

Articles Health of men, women, and children in post-traffi cking services in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: an observational cross-sectional study Ligia Kiss, Nicola S Pocock, Varaporn Naisanguansri, Soksreymom Suos, Brett Dickson, Doan Thuy, Jobst Koehler, Kittiphan Sirisup, Nisakorn Pongrungsee, Van Anh Nguyen, Rosilyne Borland, Poonam Dhavan, Cathy Zimmerman Summary Background Traffi cking is a crime of global proportions involving extreme forms of exploitation and abuse. Yet little Lancet Glob Health 2015; research has been done of the health risks and morbidity patterns for men, women, and children traffi cked for various 3: e154–61 forms of forced labour. See Comment page e118 London School of Hygiene & Methods We carried out face-to-face interviews with a consecutive sample of individuals entering 15 post-traffi cking Tropical Medicine, London, UK (L Kiss PhD, C Zimmerman PhD, services in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam. We asked participants about living and working conditions, experience N S Pocock MSc); International of violence, and health outcomes. We measured symptoms of anxiety and depression with the Hopkins Symptoms Organization for Migration, Checklist and post-traumatic stress disorder with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, and used adjusted logistic Bangkok, Thailand (D Thuy MA, regression models to estimate the eff ect of traffi cking on these mental health outcomes, controlling for age, sector of V A Nguyen MA, B Dickson BA, P Dhavan MPH, R Borland MA, exploitation, and time in traffi cking. N Pongrungsee, K Sirisup); International Organization for Findings We interviewed 1102 people, of whom 1015 reached work destinations. Participants worked in various sectors Migration, Phnom Penh, including sex work (329 [32%]), fi shing (275 [27%]), and factories (136 [13%]). -

Philanthropic Foundations and Development Co-Operation

Philanthropic Foundations and Development Co-operation Philanthropic Foundations and Development Co-operation Off-print of the DAC Journal 2003, Volume 4, No. 3 www.oecd.org Philanthropic Foundations and Development Co-operation Off-Print of the DAC Journal 2003, Volume 4, No. 3 Development Assistance Committee ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shall promote policies designed: – to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; – to contribute to sound economic expansion in member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and – to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations. The original member countries of the OECD are Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The following countries became members subsequently through accession at the dates indicated hereafter: Japan (28th April 1964), Finland (28th January 1969), Australia (7th June 1971), New Zealand (29th May 1973), Mexico (18th May 1994), the Czech Republic (21st December 1995), Hungary (7th May 1996), Poland (22nd November 1996), Korea (12th December 1996) and the Slovak Republic (14th December 2000). -

Report Memoria

Memoria2010Report Tu esfuerzo, nuestro compromiso Your effort, our commitment Las líneas de este gráfico muestran la evolución del índice de salud entre 1970 y 2010, según datos oficiales del PNUD. La línea azul representa a España; el resto corresponde a los países donde interviene Anesvad. The lines in this graph show the evolution of the health index between 1970 and 2010, according to official PNUD data. The blue line represents Spain; the rest shows countries in which Anesvad works. Redacción, Edición y Fotografías: Fundación Anesvad Diseño Gráfico: Koncepto Imprenta: Mcc Graphics Writing, Editing and Photography: Fundación Anesvad Graphic design: Koncepto Printing: Mcc Graphics Esta publicación está impresa en papel con Certificación Forestal (PEFC), garantizando que la materia prima para su fabricación proviene de bosques gestionados con criterios de sostenibilidad y uso racional. This publication is printed on paper with Forest Certification (PEFC), which guarantees that the raw materials come from sustainable forests. Al mismo tiempo, la empresa editora ha obtenido la Certificación de la Cadena de Custodia, mediante la cual garantiza el seguimiento de los materiales certificados desde el bosque hasta el producto final. The publisher also has the Custody Chain Certification, by which it guarantees tracing of raw materials from the forest to the final product. Los contenidos de esta publicación están sujetos a una licencia Creative Commons 3.0 Unported. Se permite su reproducción y difusión sin fines comerciales, siempre y cuando se cite la fuente. Cualquier alteración, transformación o derivación de esta obra sólo puede distribuirse bajo una licencia idéntica a ésta. Para ver una copia, visite http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/deed.es. -

Transforming

TRANSFORMING 2012 ANNUAL LIVES REPORT TRANSFORMING LETTER FROM OUR CEO 2012 ANNUAL Dear Friends of PCI, REPORT LIVES Despite the uncertainties of the economic environment in 2012, PCI closed CONTENTS the year on strong footing with our impact, programs and financial support OUR VISION all continuing to grow. This annual report highlights some of our continuing initiatives and most important priorities as we finished 2012 and look ahead Motivated by our concern for the world’s most vulnerable in our 2013-2016 Strategic Plan. children, families, and communi- ties, PCI envisions a world where abundant resources are shared, We’ve set a very ambitious goal: to reach and help transform the lives of ten communities are able to provide million people over the next three years. We know from all our experience that for the health and well-being of their members, and children even in the most disadvantaged circumstances people have the will and the 1LETTER FROM OUR CEO 12INTEGRATION IN ACTION can achieve lives of hope, good ability to change their own lives. When we provide the tools, training and health, and self-sufficiency. resources they need, they will lift themselves out of poverty and create a future of real hope, improved health and economic self-sufficiency for their families. OUR MISSION The stories in the following pages offer inspiring examples of personal, PCI’s mission is to prevent community and national transformational change that is occurring through- disease, improve community health, and promote sustainable out all our programs around the world. Our economic and social empowerment development worldwide. -

Financial Report and Audited Financial Statements

General Assembly A/71/5/Add.8 Official Records Seventy-first Session Supplement No. 5H United Nations Population Fund Financial report and audited financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2015 and Report of the Board of Auditors United Nations New York, 2016 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ISSN 0257-0629 Contents Chapter Page Letters of transmittal ............................................................ 5 I. Report of the Board of Auditors on the financial statements: audit opinion ................ 7 II. Long-form report of the Board of Auditors .......................................... 9 Summary ...................................................................... 9 A. Mandate, scope and methodology ............................................. 13 B. Findings and recommendations ............................................... 14 1. Follow-up on previous recommendations ................................... 14 2. Financial overview ..................................................... 14 3. Internal control system .................................................. 16 4. Programme management ................................................ 18 5. Procurement management................................................ 21 6. Results-based management ............................................... 22 7. Human resources management ............................................ 23 8. Inventory management -

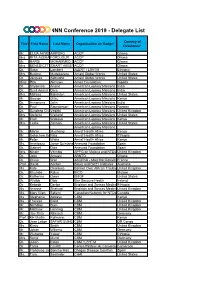

NNN Conference 2019 - Delegate List

NNN Conference 2019 - Delegate List Country of Title First Name Last Name Organisation on Badge* Residence* Mr. ELIJA AKYENAAMPOFO ACCP Ghana Mrs. RITA ABEKAHFORDJOUR ACCP Ghana Mr. HARDI MOHAMMED SANIACCP Ghana Mrs. BENEDICTTASMART NAA ASAMANUAH ABBEYACCP Ghana Dr. Saba Lambert ALERT / LSHTM Ethiopia Mrs. Busime Mudekereza Amani Global Works United States Dr. Jacques Sebisaho Amani Global Works United States Miss Rita Aimiuwu Amen Foundation Nigeria Dr. Shyamala Anand American Leprosy Missions India Dr. Sunil Anand Dara American Leprosy Missions India Mrs. Melissa Edmiston American Leprosy Missions United States Mr. George Gitau American Leprosy Missions Kenya Dr. Annamma John American Leprosy Missions India Dr. Paul Saunderson American Leprosy Missions Norway Dr. Sundeep ChaitanyaVedithi American Leprosy Missions United Kingdom Mrs. Stefanie Weiland American Leprosy Missions United States Mr. Eroll Wekesa American Leprosy Missions Kenya Mrs. Leslie Zolman American Leprosy Missions United States American Leprosy Missions Mr. Martin Muchangi Amref Health Africa Kenya Mr. Getachew GebreselassieNida Amref Health Africa Ethiopia Mr. Peter Waka Amref Health Africa Kenya Ms. Arantzazu Jorge Quintana Anesvad Foundation Spain Dr. Gabriel Diez Anesvad Foundation Spain Mrs. Nicole Vecchio APPG on Malaria and NTDs United Kingdom Dr. John Amuasi ARNTD Ghana Dr. Olivier Weil ASCEND - Mott MacDonald France Prof. David Ascher Baker and Bio21 Institutes Australia Ms. Kate Okonkwo Banner Over African TroublesUnited (BOAT) Kingdom Dr. Khumbo Kalua BICO Malawi Dr. Katherine Owen BMGF United States Dr. Wldibb Dibb Bon Secours Health Ireland Dr. Kebede Deribe Brighton and Sussex MedicalEthiopia School Ms. Arianne Shahvisi Brighton and Sussex MedicalUnited School Kingdom Ms. Mary Ellen Sellers Canadian Network for NTDs Canada Ms. -

Exploitation, Violence, and Suicide Risk Among Child and Adolescent Survivors of Human Trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion

Research Original Investigation Exploitation, Violence, and Suicide Risk Among Child and Adolescent Survivors of Human Trafficking in the Greater Mekong Subregion Ligia Kiss, PhD; Katherine Yun, MD; Nicola Pocock, MSc; Cathy Zimmerman, PhD Editorial at IMPORTANCE Human trafficking and exploitation of children have profound health jamapediatrics.com consequences. To our knowledge, this study represents the largest survey on the health of child and adolescent survivors of human trafficking. OBJECTIVE To describe experiences of abuse and exploitation, mental health outcomes, and suicidal behavior among children and adolescents in posttrafficking services. We also examine how exposures to violence, exploitation, and abuse affect the mental health and suicidal behavior of trafficked children. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A survey was conducted with 387 children and adolescents aged 10 to 17 years in posttrafficking services in Cambodia, Thailand, or Vietnam, which along with Laos, Myanmar, and Yunnan Province, China, compose the Greater Melong Subregion. Participants were interviewed within 2 weeks of entering services from October 2011 through May 2013. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, suicidal ideation, self-injury, and suicide attempts. RESULTS Among the 387 children and adolescent study participants, most (82%) were female. Twelve percent had tried to harm or kill themselves in the month before the interview. Fifty-six percent screened positive for depression, 33% for an anxiety disorder, and 26% for posttraumatic stress disorder. Abuse at home was reported by 20%. Physical violence while trafficked was reported by 41% of boys and 19% of girls. Twenty-three percent of girls and 1 boy reported sexual violence. Mental health symptoms were strongly associated with recent self-harm and suicide attempts. -

Social Impact Report As an Exercise in Transparency with the Social Base and Society in General

SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE INVESTMENT SOCIAL IMPACT ANESVAD REPORT DECEMBER 2018 DETERMINANTES DE LA SALUD SUMMARY 03 ABOUT US AND OUR WORK 04 COMMITMENT TO SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENTS CLASSIFIED 08 ACCORDING TO THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS (SDGs) INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO 10 ANALYSIS, ACCORDING TO ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL AND GOVERNANCE (ESG) CRITERIA 12 MEASURING SOCIAL IMPACT 16 SUCCESS STORIES COLLECTION OF DATA USED IN THIS REPORT We would like to thank all the fund managers who make the effort to publish an impact report regarding their funds and who have facilitated the collection of the data used in this report. The data were collected during the months of May and June 2019 and correspond to the period from January 1st to December 31st, 2018. In cases where there was no impact report for the indicated period we have used the data from the previous report published. ABOUT US AND OUR WORK At Anesvad we fight against the neglected diseases that threaten millions of people’s lives in Sub-Saharan Africa. Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws, and lymphatic filariasis are the four Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) that form the basis of our work. The manifestation of these four NTDs share similarities: it occurs via the skin, becoming extremely aggressive and sometimes resulting in life-long disability. However, the physical marks are not the only lasting consequences for those who 2018 manage to overcome these diseases: they also lead to stigmatisation, social and occupational exclusion and diminished self-esteem. At Anesvad we pool our efforts and we are therefore aligned with the World Health Organisation’s 2020 Road Map.