VOST Victoria: Coverage of the Hazelwood Mine Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “Morwell Post”

Morwell Historical Society Inc. www.latrobecityonline.com AOO 16986 W c. 1903 The “MorwellMay 2002 Post” December 2006 Vol. 23 No.6 Secretary: Elsie McMaster 2 Harold Street Morwell Tel: 5134 1149 Compiled by: Stephen Hellings Published every two months 2006 A Brief Review It has been, on the whole, a successful year for our society. A good deal of time and effort went into the move to our new premises in Buckley Street. We are now well settled in the new rooms and able to display items from our collection which had previously been kept in storage due to lack of space. Members have participated in the planning and development of Legacy Place and the unveiling of a bust in honour of Sir Stanley Savige, and also in the development and enhancement of the facilities at the Town Common. We have also enjoyed visits to other local history Societies and have been part of the Latrobe Combined History Group and the Gippsland Association of Affiliated Historical Societies. At our Annual Dinner in October guests Dianne and Graham Goulding gave us a fascinating “The Post” account of their experiences while teaching in Derham’s Hill (final) p. 2 China, and we were pleased to co-host, with Changing face of Morwell p. 4 Traralgon Historical Society, a visit by the Starling Shoot 1929 p. 5 National Trust Photographic Committee. Church Street Motors (ad) p. 6 Morwell Shire Presidents p. 7 A challenge which we face in 2007 is to increase Burglary Gude’s Arcade p. 8 our membership, which has fallen somewhat Obituary (Mrs Kaye 1906) p. -

2012 Gippsland Flood Event - Review of Flood Warnings and Information Systems

2012 Gippsland Flood Event - Review of Flood Warnings and Information Systems TRIM ID: CD/12/522803 Date: 21 November 2012 Version: Final OFFICE of the EMERGENCY SERVICES COMMISSIONER Page i MINISTERIAL FOREWORD In early June this year, heavy rain and widespread flooding affected tens of thousands of Victorians across the central and eastern Gippsland region. The damage to towns and communities was widespread – particularly in the Latrobe City, Wellington and East Gippsland municipalities. Homes, properties and businesses were damaged, roads and bridges were closed, and more than 1500 farmers were impacted by the rains. A number of people were rescued after being trapped or stranded by the rising waters. Following the floods, some communities had a perception that telephone-based community warnings and information had failed them. As the Minister for Police and Emergency Services, I requested Victoria’s Emergency Services Commissioner to review the effectiveness, timeliness and relevance of the community information and warnings. This report has met my expectations and has identified the consequences and causes for the public’s perception. I welcome the review’s findings. I am confident these will, in time, lead to better and more effective arrangements for community information and warnings and contribute to a safer and more resilient Victoria. PETER RYAN Minister for Police and Emergency Services Page ii Contents Glossary ......................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 1 1. June 2012 Gippsland flood.................................................................................3 1.1 Key physical aspects of the 2012 Gippsland flood event 3 1.2 Key aspects of information and warnings in the incident response 6 1.2.1 Key information and warnings from Bureau of Meteorology 6 1.2.2 Key information and warnings through incident management 7 2. -

South Gippsland, Victoria

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Summary of Fires - South Gippsland, Victoria: January/February 2009 ! ! ! ! Badger Reefton Upper UPPER ! Yeringberg ! Creek Yarra Dam YARRA Violet O'Keefe ! RESERVOIR ! Mcguire ! ! Mcmahons ! ! ! Town Aberfe!ldy Creek ! ! Swingler Cullen ! ! ! Map Area Legend ! Toner Coldstream ! ! Toombon ! ! ! ! Gruyere ! ! ! ! Warburton ! East Mildura -

Morwell Historical Society Inc

Morwell Historical Society Inc. www.morwellhistoricalsociety.org.au AOO 16986 W c. 1903 The “MorwellMay Post” April20022009 Vol. 26 No.2 Secretary: Elsie McMaster 2 Harold Street Morwell Tel: 5134 1149 Compiled by: Stephen Hellings Published every two months: February to December OFFICE BEARERS 2009 At the Annual General Meeting held on March 18th, the following office bearers were elected: Leonie Pryde – President Alan Davey – Vice-President and Treasurer Bruce McMaster- Archivist Stephen Hellings-Newsletter Editor Kellie Bertrand-Webmaster Ordinary Committee Members: Carol Smith, Graeme Cornell Acquisition Committee – Barry Osborne, Graeme Cornell, Joyce Cleary “The Post” There were no nominations for the position of Secretary, Porter Obituary (1966) p. 2 which remains vacant. Correspondence can be sent c/ - McRoberts Ad. (1953) p. 4 former Secretary Elsie McMaster until further notice. Cr. Hall (1909) p. 5 ANZ Bank p. 6 Morwell Police (1954) p. 7 Meetings will continue to be held on the third Wednesday Decimal Currency (1965) p. 8 of the month at 2.30 pm, and annual membership fees Sharpe’s Emporium (1966) p. 9 remain at $17.00 single membership, $20.00 couple or Woolworth’s new store (1965) p. 11 family. Morwell Fact File p. 12 Elsie McMaster PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Morwell Advertiser 14th. July 1966 PIONEER SPENT HIS 84 YEARS IN MORWELL Mr Arthur Porter, of Bolding’s Road Hazelwood North, who spent the whole of his 84 years of life in Morwell district, passed away at the Traralgon Hospital on Sunday. He was born in Morwell on October 1st, 1881, and received his education at the Morwell State School- now the Commercial Road State School. -

Croquet in Bass Coast

Croquet In Bass Coast Presented jointly by Phillip Island and Wonthaggi Croquet Clubs MAY 2018 Why Are We Here? To seek your long term support for our five year plan. To request that funding be allocated in the 2018/2019 budget for the detail design of a new Pavilion. This common design can then be built both for the Phillip Island Croquet Club and for the Wonthaggi Croquet Club. Croquet – What it isn’t! ✗✗ ✗ Croquet – What it is! • AN INTERNATIONAL SPORT PLAYED IN 19 COUNTRIES • PLAYED TO INTERNATIONAL RULES AND STANDARDS • Current World Croquet Champion: Robert Fletcher of The Lismore Club, Victoria • Current World Team Champions: Australia Croquet – What it is! South Australian Test Team of 1951 Australia wins the World Championship - 2017 Club level played by over 9,000 registered Australians and 110,000 world-wide. Registered Australian Players State Adult NSW 3,044 VIC 2,775 QLD 1,411 SA 967 WA 699 TAS 398 Total 9,294 • Source: Graeme Thomas the Australian Croquet Association Secretary Croquet Victoria • 92 Clubs • Victoria’s Croquet Headquarters: Cairnlea (West of Melbourne) – With 12 Courts, 4 floodlit, the Largest Croquet Venue in the Southern Hemisphere – Major venue in world croquet, hosting World Championships in all forms of the sport Bass Coast is home to 22% of the players in the Gippsland Region Club Membership Phillip Island 45 • Average membership in 2014 was 21. Bairnsdale 44 Average membership today is 27 Wonthaggi 40 Traralgon 35 • Since 2008 Wonthaggi membership Lakes Entrance 31 has grown from 15 to 40; a sustained rate of over 10% per annum. -

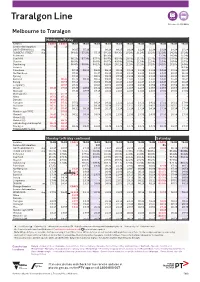

Traralgon Line AD Effective 31/01/2021 Melbourne to Traralgon

Traralgon Line AD Effective 31/01/2021 Melbourne to Traralgon Monday to Friday Service COACH COACH TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN TRAIN Service Information ∑ ∑ SOUTHERN CROSS dep 06.05 07.16 08.26 09.25 10.24 11.24 12.24 13.24 14.24 15.24 FLINDERS STREET dep 06.10u 07.23u 07.39 08.31u 09.30u 10.29u 11.29u 12.29u 13.29u 14.29u 15.29u Richmond – – – 08.36u – – – – 13.34u 14.34u 15.34u Caulfield 06.23u 07.38u 07.54u 08.45u 09.44u 10.43u 11.43u 12.43u 13.43u 14.43u 15.43u Clayton 06.33u – 08.03u 08.57u 09.58u 10.54u 11.54u 12.54u 13.54u 14.54u 15.53u Dandenong 06.47u 08.04u 08.17u 09.10u 10.11u 11.10u 12.10u 13.10u 14.10u 15.10u 16.08u Berwick – – – – – – – – – – 16.18u Pakenham 07.10 08.23 08.42 09.30 10.29 11.29 12.29 13.29 14.29 15.29 16.27 Nar Nar Goon 07.15 – 08.47 09.35 10.34 11.34 12.34 13.34 14.34 15.34 16.33 Tynong 07.19 – 08.51 09.39 10.38 11.38 12.38 13.38 14.38 15.38 16.37 Garfield 06.45 07.23 08.33 08.55 09.43 10.42 11.42 12.42 13.42 14.42 15.42 16.41 Bunyip 06.50 07.28 – 09.00 09.48 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 16.45 Longwarry 06.55 07.31 – 09.03 09.51 10.50 11.50 12.50 13.50 14.50 15.50 16.49 Drouin 05.45 07.06 07.38 08.53 09.10 09.58 10.57 11.57 12.57 13.57 14.57 15.57 16.55 Warragul – – 07.44 08.59 09.16 10.04 11.03 12.03 13.03 14.03 15.03 16.03 17.02 Warragul (1) 05.55 07.18 – – – – – – – – – – – Nilma 05.59 07.22 – – – – – – – – – – – Darnum 06.02 07.25 – – – – – – – – – – – Yarragon 06.07 07.31 07.52 – 09.24 10.12 11.11 12.11 13.11 14.11 15.11 16.11 17.09 Trafalgar 06.15 07.37 07.58 – -

The Hazelwood Coal Mine Fire: Lessons from Crisis Miscommunication and Misunderstanding

Volume 4 2015 www.csscjournal.org ISSN 2167-1974 The Hazelwood Coal Mine Fire: Lessons from Crisis Miscommunication and Misunderstanding Jim Macnamara University of Technology Sydney Abstract When a bushfire ignited the Hazelwood coal mine in the Latrobe Valley 150 kilometers (95 miles) east of Melbourne, Australia, in 2014 and burned for 45 days sending toxic smoke and ash over the adjoining town of Morwell, crisis communication was required by the mine company, health and environment authorities, and the local city council. What ensued exposed major failures in communication, which resulted in widespread community anger and a Board of Inquiry. This critical analysis examines public communication during the crisis and the subsequent clean-up, and it reports several key findings that inform crisis communication theory and practice. Keywords: natural disaster; emergency; crisis communication; emergency communication; public relations Introduction In February 2014 in the heat of the Australian summer, savage bushfires swept through the Latrobe Valley in the southern Australian state of Victoria, causing substantial damage to houses, livestock, wildlife, and the environment. In addition to constituting a crisis by themselves, the bushfires sparked a much longer lasting and potentially disastrous crisis when they ignited the Hazelwood open cut coal mine. Brown coal in the mine caught alight and burned for 45 days before being extinguished. In the process, the coal mine fire spread thick smoke and ash containing To cite this article Macnamara, J. (2015). The Hazelwood coal mine fire: Lessons from crisis miscommunication and misunderstanding. Case Studies in Strategic Communication, 4, 54-87. Available online: http://cssc.uscannenberg.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/v4art4.pdf Macnamara The Hazelwood Coal Mine Fire potentially dangerous chemicals and particles over the adjoining town of Morwell. -

Morwell National Park

Morwell National Park Billys Creek Area The Billys Creek area was added to Morwell National Park between 1989 and 1991 to provide a wider range of recreational opportunities and a greater sample of the StateÕs natural environments than were previously available in the Fosters Gully area. (See separate Morwell National Park notes). About the area Lodge Track – 2 km It is an area of great natural beauty with high From Billys Creek Weir to Morans Road. scenic values and relics of past land uses. Areas This track climbs steeply up a ridge through a of remnant Strzelecki Ranges vegetation can be variety of forest types containing Blue Gum, seen, along with previously degraded areas which Mountain Grey Gum, Messmate and Apple Box have been rehabilitated; over 25,000 trees have (But But). A strenuous walk, but the views from been planted on the creek flats between Junction the higher areas of the Park make it worthwhile. Road and the Billys Creek weir. Recreational activities include picnicking, bird watching, nature Clematis Track – 1.2 km study and bushwalking. From Billys Creek to Lodge Track. In the future a carpark and picnic facilities will be developed beside Billys Creek and the public will Climbing through a damper forest type which have access from Braniffs Road. contains Blackwoods and Musk-daisy Bush, this track joins Lodge Track half way up on its climb This brochure outlines some of the walking tracks to Morans Road but is not quite as steep. Clematis in the area ranging from steep tracks venturing and Wonga Vine can be seen flowering profusely into the more remote, but highly scenic parts of all along this track in early spring. -

Latrobe Valley Social History

Latrobe Valley Social History History Social Valley Latrobe Latrobe Valley Social History Celebrating and recognising Latrobe Valley’s history and heritage Celebrating and recognising Latrobe Valley’s history heritage and Latrobe Valley’s recognising and Celebrating Contents Acknowledgements 2 Chapter 3: Communities 69 First peoples 70 Acronyms 3 Co-existence, the mission era and beyond 71 Preface 5 Settler communities 72 Small towns and settlements 73 Introduction 7 Large town centres 74 Housing 77 Chapter 1: Land and Water 9 Town and community life 80 Evolution of a landscape 12 The importance of education 82 Ancient land, ancient culture 14 Sport, recreation and holidays 84 Newcomers 19 Women’s social networks 86 Frontier conflict 21 Church communities 87 Mountain riches 24 Health and hospitals 88 A ‘new province’ 25 Migration 91 Responses to the landscape 28 Don Di Fabrizio: From Italy to Morwell 95 Access to the Valley 30 Lost places 96 Fire and flood 33 Looking back, looking forwards 98 Transforming the land 35 Pat Bartholomeusz: Dedicated to saving a town Hazelwood Pondage 37 and a community 99 Reconnecting to Country 100 Chapter 2: Work and Industry 39 Conclusion 101 Introduction 40 Aboriginal workers 41 Bibliography 103 Mining and timber-cutting 42 Primary sources 104 Farming and the growth of dairying 44 Maps and Plans 104 The promise of coal 46 Published Works 104 A State-run enterprise for winning coal 49 Industrial History 105 Ray Beebe: a working life with the SEC 52 Government Reports, Publications and Maryvale paper mill -

Central Gippsland Junior Football League Inc

Central Gippsland Junior Football League Inc. PRESIDENT SECRETARY Mathew Snell 0430 017 240 Steve Gent 0417 113 723 [email protected] [email protected] Leaders in Junior Football www.cgjfl .vcfl.com.au 2018 HANDBOOK Including 2017 Annual Report 2017 Under 14 Interleague Grand Final Winners Central Gippsland Junior Football League Inc. A.B.N. 25 109 771 580 1 P.O. Box 20 Newborough Vic 3825 Proudly Supported by Energy Australia CGJFL LEAGUE OFFICIALS - 2018 President Mathew Snell 0430 017 240 [email protected] Vice President Grant Coultard 0411 037 317 Treasurer Mick Maroney 0423 031 626 [email protected] Secretary Steve Gent 0417 113 723 [email protected] Executive Members Mick Hanily, Nick Matthews Score Secretary Veronica Hanily 0408 134 270 [email protected] Central Gippsland Junior Football League Inc. A.B.N. 25 109 771 580 2 P.O. Box 20 Newborough Vic 3825 Proudly Supported by Energy Australia 2018 CLUB CONTACTS Hill End & Grove Rovers (1980) President Paul Mann 0402 931 668 Secretary: - Louise Paul 0498 961 057 [email protected] Hill End & Grove Rovers JFC PO Box Willow Grove 3825 Leongatha (2001) President Michael Hanily 0417 311 756 Secretary: - Alister Fixter 0458 625 362 [email protected] PO Box 27 Leongatha Vic 3953 Moe Lions (1972) President Mark Walsh 0428 564 008 Secretary: - Linda Weir 0458 276 436 [email protected] Moe Lions JFC PO BOX 85 MOE VIC 3825 Mirboo North (1992) President Mick Bradley 0499 925 770 Secretary: - Rachel Woodall 0467 466 782 [email protected] Mirboo North JFC P.O.Box 37 Mirboo North, Vic 3871 Morwell Junior Football (2003) President: Anthony Bloomfield 0438 962 055 Secretary: - Keith Kerstjens 0400860257 [email protected] PO BOX 496 Morwell, Vic 3840 Central Gippsland Junior Football League Inc. -

Ash Residue in Morwell Roof Cavities Community Report – May 2017 Contents

Ash residue in Morwell roof cavities Community report – May 2017 Contents Background 3 Project overview 4 Background research 4 About Senversa 5 Sampling plan 6 Sample collection 6 Public consultation and community engagement 7 Overview of sampling and results 8 Detailed findings 9 Indoor dust 12 Mould 12 Health investigation levels 12 Frequently used terms 13 Conclusions 14 Recommendations 15 To receive this publication in an accessible About this report format phone 1300 761 874, using the National This is a summary version Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email of Senversa’s comprehensive [email protected] final project report. Copies of Senversa’s report and all other Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, documents relating to this 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. project can be accessed © State of Victoria, May 2017 at www.health.vic.gov.au/ Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show ash-project or requested by models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual emailing [email protected]. services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. gov.au or phoning 1300 761 874. Available at www.health.vic.gov.au/ash-project Printed by Sunnyland Offset, Mildura on sustainable paper. (1704011) 2 Ash residue in Morwell roof cavities Background On 9 February 2014, embers from nearby bushfires In its third report (Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry started a fire in the Hazelwood open-cut brown Report 2015/2016 Volume III—Health Improvement), coal mine. The Hazelwood coal mine is on the the Board of Inquiry recommended that the State: southern edge of Morwell, a town of nearly “Ensure that ash contained in roof cavities 14,000 people in regional Victoria. -

Welcome to Latrobe City

WELCOME TO LATROBE CITY Latrobe City, also known as Latrobe Valley, is a vibrant regional City with a population of over 75,000 people. It is recognised as one of the four major Victorian regional cities and one of the fastest growing nonmetropolitan centres in Australia. The City is made up of four major urban centres: Churchill, Moe/Newborough, Morwell and Traralgon, with seven smaller townships of Boolarra, Glengarry, Toongabbie, Tyers, Traralgon South, Yallourn North and Yinnar. The beautiful and highly productive Latrobe Valley is located at the gateway to Gippsland in the South East corner of the state of Victoria. Latrobe City is diverse, substantial and really is a new energy in regional Australia.NED MORE INFORMATION?Contact the Latrobe Visitor Information1409 W ebsi TRAVEL DISTANCES Melbourne City to Morwell 150 km Melbourne City to Traralgon 163 km Morwell to Churchill 11 km Traralgon to Churchill 20km GETTING THERE From Melbourne Airport (Tullamarine): By Skybus: Skybus offers a convenient and frequent transport service between Melbourne Tullamarine Airport and Southern Cross railway station in central Melbourne. More information about Skybus service and timetable. By Taxi to Melbourne CBD: Taxis are on standby at Melbourne Airport, approximately 25 minute drive. By car Following City Link (electronic tollway) will bring you towards Melbourne, South Eastern Suburbs and the M1 Freeway. Follow signpost to M1 Freeway, South Eastern suburbs and Warragul from Melbourne. IMPORTANT: To travel on the City Link tollway, you will need to purchase a pass (if you do not have an E-Tag). Find out more information or purchase a City Link Pass or phone 13 26 29.