India's Tryst with 5G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(POSTHUMOUS) Since His Enrolement in the Army, Lance Naik

ASHOK CHAKRA LANCE NAIK NAZIR AHMAD WANI, BAR TO SENA MEDAL THE JAMMU AND KASHMIR LIGHT INFANTRY / 34TH BATTALION THE RASHTRIYA RIFLES (POSTHUMOUS) Since his enrolement in the Army, Lance Naik Nazir Ahmad Wani, SM**, epitomised qualities of a fine soldier. He always volunteered for challenging missions, displaying great courage under adverse conditions, exposing himself to grave danger on numerous occasions in the line of duty. This is evident from the two gallantry awards conferred on him earlier. Lance Naik Nazir, yet again insisted on being part of the assault team during Operation Batagund launched by 34 Rashtriya Rifles Battalion on 25 Nov 2018 post receipt of credible intelligence regarding presence of six heavily armed terrorists in Shopian district of Jammu and Kashmir. Tasked to block the most likely escape route, Lance Naik Nazir, moved swiftly with his team to the target house and tactically positioned himself within striking distance. Sensing danger, the terrorists attempted breaching the inner cordon firing indiscriminately and lobbing grenades. Undeterred by the situation, the NCO held ground and eliminated one terrorist in a fierce exchange at close range. The terrorist was later identified as a dreaded district commander of Lashker-e-Taiba. Thereafter, displaying exemplary soldierly skills, Lance Naik Nazir closed in with the target house under heavy fire and lobbed grenades into a room where another terrorist was hiding. Seeing the foreign terrorist escaping from the window, the NCO encountered him in a hand to hand combat situation. Despite being severely wounded, Lance Naik Nazir eliminated the terrorist. Showing utter disregard to his injury, Lance Naik Nazir continued to engage the remaining terrorists with same ferocity and audacity. -

Chinese Defence Reforms and Lessons for India

Chinese Defence Reforms and Lessons for India D S Rana Introduction Since the formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), China’s defence forces have evolved through various stages of modernisation with a focus on doctrinal changes, structural reforms, as well as reduction of forces. Post Mao era, the first sincere attempt to infuse professionalism in the outdated People’s Liberation Army (PLA) commenced in the true sense, when ‘national defence’ was made one of the ‘Four Modernisations,’ as announced by Deng Xiaoping in 1978. This boost towards military modernisation was catalysed by the reduced threat perception post disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 and greater allocation in the defence budget for upgradation post 1995, as boosted by an improved Chinese economy. The display of high-end technology by the US in the Gulf War and its outcome forced the Chinese brass for the first time to acknowledge the PLA’s shortcomings for future wars, and served as a trigger for the present stage of reforms.1 As a result of the assessed “period of strategic opportunity” by China in the beginning of the 21st century and the consequent Hu Jintao’s new set of “historic missions” for the PLA, the concept of ‘the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) with Chinese characteristics’ was enunciated through China’s 2004 National Defence White Paper. As a follow-up, the timeline for the modernisation of the Brigadier D S Rana is presently posted as Directing Staff in the Higher Command Wing, Army War College, Mhow. 138 CLAWS Journal l Summer 2019 CHINESE DEFENCE REFORMS AND LESSONS FOR INDIA PLA was laid out in three steps in the following 2006 White Paper. -

Rifleman Sanjay Kumar (13 JAK Rif)

My Kargil War Hero The Overview July 26, it was on this day 22 years ago that the Indian Army recaptured all the Indian posts in Kargil that were captured by the Pakistan Army. Since then July 26 has been observed annually, as Kargil Vijay Diwas, to honour the supreme scarifies and the exemplary courage of the Brave Hearts who laid down their lives safeguarding the frontiers of our motherland. After the Lahore Summit in 1999 the diplomatic tensions seemed to ease. But the sense of optimism seemed to be short-lived as in May 1999 Pakistan Paramilitary forces and Karshmir insurgents captured deserted but strategic posts in the Himalayan heights of Kargil. These posts were vacated by the Indian Army on the account of the inhospitable winter and were supposed to be reoccupied in spring. The Pakistani forces positioned themselves in locations that enable them to bring NH1 within its range of artillery fire. Once the scale of Pakistani incursion was realised , the Indian Army quickly moralised around 2,00,000 troops and gave a buffeting response. Backed by Indian Air Force, Indian Army launched Operation Vijay and captured the curial points of Tiger Hill and Tololing in Drass. The Army declared the mission successful on July 26, 1999; since it has been marked as the Kargil Vijay Diwas in India. Remembering the War Heroes India’s victory at the heights of the Kargil was a hard earned one. The victory came at the cost of the several supreme sacrifices by the Sons of the Soil. Captain Vikram Batra, (13 JAK RIF) Captain Vikram Batra of the 13 Jammu and Kashmir Rifle immortalised himself by fighting Pakistani forces during the Kargil war in 1999 at the age of 24. -

¼ÛT.¾.Hðgå.Gż.ºhá¼ü REG

¼ÛT.¾.hÐGÅ.Gż.ºHá¼ü REG. No. JKENG/2013/55210 Rs. 15/- R EACH VOL. 7 ISSUE 13 PAGES 8 L ADAKH B ULLETIN July 16-31, 2019 Fortnightly Special Commemorating the 20th Anniversary of Kargil Vijay Diwas Page 4-5 Find us on FACEBOOK: Reach Ladakh Follow us on twitter: ReachLadakhBulletin Visit our website: www.reachladakh.com Brief News Defence Minister lights ‘Victory Flame’ Yarchos Chenmo begins with religious fervour DISCLAIMER to mark 20 years of Kargil Vijay Diwas Reach Ladakh does not take re- sponsibility for the contents of the Advertisements Display/classified published in this newspaper. The paper does not endorse the same. Readers are requested to verify the contents on their own before acting there upon. Reach Ladakh Correspondent mo would help to promote good tradi- tional practices and discourage ill prac- NUBRA: The nine-day lDumra Khadot tices like caste system and alcoholism. Yulsum Yarchos Chenmo begins with re- ligious fervour on July 15. In commemoration with Khadot Yarchos Chenmo, the Cultural Academy Leh has Subscribe to our You Tube Channel Reach Ladakh Correspondent tyrs and all along the journey and hom- Ven. Geshe Thupstan Rabgyas (Spiritu- organized a 5-day cultural training to the age will be paid to the heroes who fought al guidance of His Eminence Ling Rin- people of this area and to mark the occa- ‘Reach Ladakh’ to get all the latest NEW DELHI: Marking the 20th anni- updates from Ladakh and don’t forget valiantly for the Nation. poche) who was the chief guest on the sion, a cultural programme was present- versary of the Operation Vijay, Rajnath occasion hoped that Khadot Yarchos to click the notification bell Rajnath Singh along with Gen Bipin ed by the trainees. -

Aan-Comics-Param-Vir-Comic

Ready and raring to go, 1 2 Bana? 4 Bana is first 5 NAIB SUBEDAR /HON CAPT to reach ... But the the top The jawans BANA SINGH men brave the break conditions and open the keep climbing bunker door SIACHEN 1987 and lob 8 grenades June 1987 Pakistanis had set up Quaid post on Siachen. The domi- nating heights allowed them to fire at Indian posts. The Indian army launched an operation to evict them. 8 Yes sir, we JAKLI was to do the honours shall not fail you 6 3 The heavy snow will give us cover, come THE LIVING on boys… LEGENDS 7 That’s them! INDIA’S FINEST Three war heroes who exemplify courage and patriotism. Read their stories in a comic strip by Rishi Kumar The troops encounter a heavy snowstorm, almost blinding them There are only three principles of warfare — audacity, audacity and audacity” —famous The explosion draws the attention 9 Bana sees them coming 10 11 12 SIACHEN HERO words from American World War II hero, George of Pakistani troops nearby and they Take that S Patton. come to investigate Eventually, the weather clears Leading a five-man army, Bana Singh, Sanjay Kumar and Yogendra Yadav have Bana Singh launched a fierce no link to Patton —other than the audacity they showed Pak1: What assault on the Quaid post “ was that, are in different conflicts for India, courageous feats that won we under held by the Pakistani army them the country’s highest wartime gallantry award, the attack? in April 1987. They killed five Param Vir Chakra. -

CERTIFICATE COURSE in BUSINESS MANAGEMENT for DEFENCE OFFICERS Placement Brochure 2021 Disciplines Ofmanagementeducation

CERTIFICATE COURSE IN BUSINESS MANAGEMENT FOR DEFENCE OFFICERS PLacement brocHURE 2021 Offering various management development programmes, IIM Indore is at the helm of training business leaders, senior executives and practicing managers from various industry and disciplines of management education. The Message Institute from the Coordinator 01 Message 02 from the 02 Director ontents The Industry Programme Speaks 03C 05 Alumni 04 Messages Batch Batch 06 Statistics 10 profiles Individual 08 Interests Placement 40 Procedure THE INSTITUTE Established in 1996, as the sixth Indian Institute of Management in the country, IIM Indore is one of the premier business schools in India. The institute offers world class education in areas of management and provides an atmosphere for genuine intellectual pursuit and professional growth. The institute placed its first batch of 36 participants in less than 36 hrs. The learning curve has only been a rising one since then. Offering various management development programmes, IIM Indore is at the helm of training business leaders, senior executives and practicing managers from various industry and disciplines of management education. Large number of consulting assignments and research programs have been undertaken over these years to assist corporate houses and public agencies address critical and strategic issues and not simply improve efficiency. IIM Indore has internationally acclaimed programmes known for quality, rigour and global orientation. Bringing further credibility to the institute with a ‘Triple Crown’, i.e. receiving all the three prominent accreditations — Association of MBAs (AMBA, UK); The Association to Advanced Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB, USA); and EQUIS, European Union, the institute is the second in the country to secure the Triple accreditation status. -

Seminar Report REDEFINING the ROLE of FIREPOWER AND

Seminar Report REDEFINING THE ROLE OF FIREPOWER AND MANOEUVRE IN FUTURE CONFLICT SCENARIO IN THE INDIAN CONTEXT April 30, 2019 Seminar Coordinator: Colonel Anurag Bhardwaj Seminar Report by: Kanchana Ramanujam Centre for Land Warfare Studies RPSO Complex, Parade Road, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi-110010 Phone: 011-25691308; Fax: 011-25692347 email: [email protected]; website: www.claws.in The Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, is an independent think tank dealing with contemporary issues of national security and conceptual aspects of land warfare, including conventional and sub-conventional conflicts and terrorism. CLAWS conducts research that is futuristic in outlook and policy-oriented in approach. CLAWS Vision: To establish as a leading Centre of Excellence, Research and Studies on Military Strategy & Doctrine, Land Warfare, Regional & National Security, Military Technology and Human Resource. © 2019, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi All rights reserved The views expressed in this report are sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India, or Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army) or Centre for Land Warfare Studies. The content may be reproduced by giving due credit to the speaker(s) and the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. Printed in India by Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd. DDA Complex LSC, Building No. 4, 2nd Floor Pocket 6 & 7, Sector – C Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110070 www.bloomsbury.com CONTENTS DETAILED REPORT 1 INAUGURAL -

The Budgetary Allocation to the Army in the Recent

• India’s• Internal Defence Security Procurement • Events’ Policies Reference & Procedures - Insert • NEW IN THIS EDITION - Map: DRDO and DPSUs Headquarters Volume 10 No. 6 `100.00 (India-Based Buyer Only) TM SP’s AN SP GUIDE P UBLICATION 2013 ST TM Finmeccanica and India: in the spirit of partnership. 2013 41 41 ISSUE ISSUE ST Editor-in-Chief Price: Inland Rs 7,495; JAYANT BARANWAL Foreign (Surface Mail): Stg. £ 415.00; US$ 735.00 SP military yearbook 110x181_11.indd 1 27/06/12 10.39 SP's MYB Cover 2013 - Final.indd 1 WWW.SPSLANDFORCES.COM27/12/12 4:07 PM 589_Rafale_Press Ad 221 276.indd 1 24/08/12 12:21 ROUNDUP IN THIS ISSUE THE ONLY MAGAZINE IN ASIA-PACIFIC DEDICATED to LAND FORCES INDIAN ARMY SPECIAL PAGE 5 Indian Army through the Ages – A Bird’s-Eye View The transformation of the Indian military for the future, through technological improvements coupled with innovative operational art will give India a distinct advantage over its potential adversaries, Minister of Defence which is vital for preserving India’s MESSAGE India sovereignty and furthering its national interests. Lt General (Retd) V.K. Kapoor It is a pleasure to learn that SP Guide Publications is coming out with a special issue to commemorate Army Day. Our Army has lived up to its tradition of valour, sacrifice and fortitude. The Army protects our land borders, both PAGE 7 during peace and in warlike situations. It takes pride in the spirit of brotherhood and comradeship without any dis- Revisiting Indian Army’s Modernisation crimination. -

Capture of Tiger Hill (Op Vijay-1999)

No. 07/2019 AN INDIAN ARMY PUBLICATION July 2019 CAPTURE OF TIGER HILL (OP VIJAY-1999) GRENADIERS was tasked to capture Tiger Hill, one of the prominent features in the Drass Sub-Sector. The initial attack was led by Captain Sachin Nimbalkar and Lieutenant 18Balwan Singh, with a Section of ‘D’ Company and the Ghatak Platoon in a multi directional attack. The team stealthily approached Tiger Hill and took the enemy by surprise. Lieutenant Balwan Singh along with Havildar Madan Lal gallantly led the Section and pressed forward against heavy odds. The Section approached and engaged the Pakistani bunkers on Tiger Hill Top. During this fight Havildar Madan Lal got severe injuries but still continued to press forward. The individual showed extraordinary courage and exemplary junior leadership and was awarded Vir Chakra (Posthumously). Lieutenant Balwan Singh in another outflanking manoeuvre took the enemy by sheer surprise as his team used cliff assault mountaineering skills to reach the top. The officer single handedly killed many Pakistani soldiers, and led his team to the top. For his leadership and unmatched gallantry, Lieutenant Balwan Singh was awarded the Maha Vir Chakra. Another prominent name associated with Tiger hill is Grenadier Yogendra Singh Yadav, who was part of the leading team of Ghatak Platoon tasked to capture Tiger Hill Top. The soldier utterly disregarded his own injury that he sustained due to enemy fire and continued to charge towards the enemy bunkers all the while firing from his rifle. He killed enemy soldiers in close combat and silenced the automatic fire. He sustained multiple bullet injuries and was in critical condition, but refused to be evacuated and continued to attack. -

Kargil War Heroes

Cdt Ritu Santosh Botre 1MAH Girls BN NCC Mumbai B group JBC thane. Kargil war heroes Captain Vikram Batra, (13 JAK RIF) "I will either come back after raising the Indian flag in victory or return wrapped in it." Captain Vikram Batra of the 13 Jammu and Kashmir Rifle immortalised himself by turning a soft-drink ad's tagline "Yeh dil mange more" (My heart asks for more) into an iconic war cry while showcasing on national television the enemy's machine guns he had captured in his first gallant exploits in the Kargil war. He died fighting Pakistani forces during the Kargil war in 1999 at the age of 24. He was given the highest wartime gallantry award Param Vir Chakra posthumously. Due to his exemplary feat, Captain Vikram was awarded many titles. He came to be fondly called the 'Tiger of Drass', the 'Lion of Kargil', the 'Kargil Hero', and so on. Pakistanis called him Sher Shah after the ferocious warrior king of medieval India. Captain Vikram’s most difficult mission was the capture of crucial peak – Point 4875. He had led his team despite high fever and got fatally injured trying to save another officer. Lieutenant Balwan Singh (18 Grenadiers) "Tiger Hill pe Tiranga fahrake ayenge, chahe kuchh bhi ho jaye." ("We will hoist the Tricolour atop Tiger Hill, come what may.") Lt Balwan Singh, now a Colonel, was the Tiger of Tiger Hill -- the decisive battle of the Kargil wara. Singh was tasked with the recapture of Tiger Hill. At 25, he led soldiers of the Ghatak platoon through a steep, treacherous path on 12-hour journey to reach the hilltop. -

DETAILS of GALLANTRY AWARDEE (CHAKRA SERIES) Name : Arun

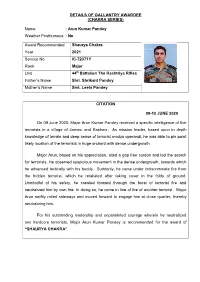

DETAILS OF GALLANTRY AWARDEE (CHAKRA SERIES) Name : Arun Kumar Pandey Weather Posthumous : No Award Recommended Shaurya Chakra Year 2021 Service No IC-72371Y Rank Major Unit 44th Battalion The Rashtriya Rifles Father’s Name Shri. Shrikant Pandey Mother’s Name Smt. Leela Pandey CITATION 09-10 JUNE 2020 On 09 June 2020, Major Arun Kumar Pandey received a specific intelligence of five terrorists in a village of Jammu and Kashmir. As mission leader, based upon in depth knowledge of terrain and deep sense of terrorist modus operandi, he was able to pin point likely location of the terrorists in huge orchard with dense undergrowth. Major Arun, based on his appreciation, sited a gap free cordon and led the search for terrorists. He observed suspicious movement in the dense undergrowth, towards which he advanced tactically with his buddy. Suddenly, he came under indiscriminate fire from the hidden terrorist, which he retaliated after taking cover in the folds of ground. Unmindful of his safety, he crawled forward through the burst of terrorist fire and neutralized him by own fire. In doing so, he came in line of fire of another terrorist. Major Arun swiftly rolled sideways and moved forward to engage him at close quarter, thereby neutralizing him. For his outstanding leadership and unparalleled courage wherein he neutralized two hardcore terrorists, Major Arun Kumar Pandey is recommended for the award of “SHAURYA CHAKRA”. DETAILS OF GALLANTRY AWARDEE (CHAKRA SERIES) Name : Ravi Kumar Chaudhary Weather Posthumous : No Award Recommended Shaurya Chakra Year 2021 Service No SS-45282W Rank Major Unit 55th Battalion The Rashtriya Rifles Father’s Name Shri. -

Seminar Report 20 YEARS AFTER KARGIL CONFLICT

Seminar Report 20 YEARS AFTER KARGIL CONFLICT July 13, 2019 Seminar Coordinator: Colonel Sunil Gupta Rapporteur: Kanchana Ramanujam and Anashwara Ashok Centre for Land Warfare Studies RPSO Complex, Parade Road, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi-110010 Phone: 011-25691308; Fax: 011-25692347; Army No.: 33098 email: [email protected]; website: www.claws.in The Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, is an independent think tank dealing with contemporary issues of national security and conceptual aspects of land warfare, including conventional and sub-conventional conflicts and terrorism. CLAWS conducts research that is futuristic in outlook and policy-oriented in approach. CLAWS Vision: To establish as a leading Centre of Excellence, Research and Studies on Military Strategy & Doctrine, Land Warfare, Regional & National Security, Military Technology and Human Resource. © 2019, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi All rights reserved The views expressed in this report are sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India, or Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army) or Centre for Land Warfare Studies. The content may be reproduced by giving due credit to the speaker(s) and the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. Printed in India by Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd. DDA Complex LSC, Building No. 4, 2nd Floor Pocket 6 & 7, Sector – C Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110070 www.bloomsbury.com CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 DETAILED REPORT 11 Aim 7 Modalities of Conduct 7 Chair 7 Opening Remarks by CLAWS Director 8 Keynote Address by Chief of the Army Staff 9 Special Address by General VP Malik Ex Chief of Army Staff 12 Special Address by General NC Vij, Ex Chief of the Army Staff and Ex Director General of Military Operations 14 Special Address by Lieutenant General Mohinder Puri, Ex-General Officer Commanding Kargil Division During Operation VIJAY and Ex Deputy Chief of the Army Staff 17 SESSION I.