Composing Educational Music for Strings in the Canadian Context: Composer Perspectives Bernard W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: a QUESTION of NATIONALISM a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satis

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: A QUESTION OF NATIONALISM A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Ronald Frederick Erin August, 1983 J:lhe Thesis of Ronald Frederick Erin is approved: California StD. te Universi tJr, Northridge ii PREFACE This thesis represents a survey of Canadian music since 1940 within the conceptual framework of 'nationalism'. By this selec- tive approach, it does not represent a conclusive view of Canadian music nor does this paper wish to ascribe national priorities more importance than is due. However, Canada has a unique relationship to the question of nationalism. All the arts, including music, have shared in the convolutions of national identity. The rela- tionship between music and nationalism takes on great significance in a country that has claimed cultural independence only in the last 40 years. Therefore, witnessed by Canadian critical res- ponse, the question of national identity in music has become an important factor. \ In utilizing a national focus, I have attempted to give a progressive, accumulative direction to the six chapters covered in this discussion. At the same time, I have attempted to make each chapter self-contained, in order to increase the paper's effective- ness as a reference tool. If the reader wishes to refer back to information on the CBC's CRI-SM record label or the Canadian League of Composers, this informati6n will be found in Chapter IV. Simi- larly, work employing Indian texts will be found in Chapter V. Therefore, a certain amount of redundancy is unavoidable when interconnecting various components. -

Season of Events

2019-2020 season of events James K. Wright, Professor of Music at Carleton University Louis Applebaum Distinguished Visitor in Film Composition presents “They shot, he scored: Eldon Rathburn and the legacy of the National Film Board” Thursday, January 23, 2020 at 7:30 pm | Walter Hall, 80 Queen’s Park The Louis Applebaum Distinguished Visitor in Composition was established by Sandra and Joseph Rotman to honour the memory of the Canadian film composer Louis Applebaum (1918-2000). James Wright is a Professor of Music at Carleton and recorded by artists and ensembles from around University, Ottawa. A McGill University Governor the globe. His Letters to the Immortal Beloved (for General’s Gold Medal recipient, Dr. Wright studied piano trio and baritone or mezzo-soprano) – settings of music theory and composition with Barrie Cabena, excerpts from Beethoven’s passionate letters of 1812, to Owen Underhill, Bengt Hambreaus, Donald Patriquin, a woman whose identity has been cloaked in mystery Brian Cherney and Kelsey Jones, and has taught – has been performed on five continents, with notable composition, music history, music perception/cognition, performances in Brazil, Portugal, China, Australia, and post-tonal music theory and analysis at McGill Canada, the Netherlands, and the USA. Two acclaimed University, the University of Ottawa, and Carleton recordings of the work have been issued by the Juno University. His scholarly contributions include two Award-winning Gryphon Trio: on the Naxos label in award-winning books on the life and work of Arnold 2015 (with mezzo-soprano Julie Nesrallah) and on the Schoenberg, and They Shot, He Scored (Montreal: Analekta label in 2019 (with baritone David Pike). -

Voices of the Land and Sea with Special Guest Jenny Blackbird

Voices of the Land and Sea with special guest Jenny Blackbird Sunday, October 21, 2018 2:30 pm Church of the Redeemer, 162 Bloor Street West MacMillan Singers David Fallis, conductor Lara Eden-Dodds, collaborative pianist Women’s Chamber Choir Lori-Anne Dolloff, conductor Valeska Cabrera, assistant conductor Eunseong Cho, pianist We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land. Program MacMillan Singers David Fallis, conductor Lara Eden-Dodds, collaborative pianist Ambe Andrew Balfour (b. 1967) Trapped in Stone Andrew Balfour Gloria Deo Healey Willan (1880-1968) She’s like the Swallow arr. Harry Somers (1925-1999) Feller from Fortune arr. Harry Somers J’entends le moulin arr. Donald Patriquin (b. 1938) Intermission Women’s Chamber Choir Lori-Anne Dolloff, conductor Valeska Cabrera, assistant conductor Eunseong Cho, pianist Of Whalers and Whales Frobisher Bay James Gordon (b. 1955) Claire Laosinsky, soprano Sorrow Song of Whales Jeff Enns Paddling Songs V’la l’Bon Vent arr. Allison Girvan Valeska Cabrera, conductor Solo Quartet: Abigail Sinclair, Ineza Mugisha, Dayie Chung, Alyssa Meyerowitz Grammah Easter’s Lullaby Pura Fé (b. 1960) The Silent Voices For those who cannot go home again Jenny Blackbird Jenny Blackbird and the Faculty of Music Singing and Drumming Ensemble Our Inland Sea Begin Alice Ping Yee Ho (b. -

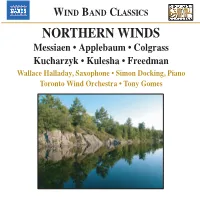

NORTHERN WINDS Globe and Mail for His “Effortless Virtuosity” in Contemporary Music, He Has Given the Performance of Several Masterpieces

572248 bk NW 10/31/08 1:21 PM Page 5 Simon Docking Toronto Wind Orchestra WIND BAND CLASSICS Australian-born pianist Simon Docking has performed both as a soloist and chamber Toronto Wind Orchestra was founded in 1994 by Dr Mark Hopkins, assisted by Tony Gomes, with a mission to give musician throughout North America, as well as in Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and professional performances of rare and unusual wind repertoire. In 1999 Tony Gomes assumed the position of Music Europe. He studied piano in Australia with Ransford Elsley, and holds a doctorate in piano Director of the ensemble. Toronto Wind Orchestra includes some of Toronto’s finest freelance performers who performance from SUNY Stony Brook, where he worked with Gilbert Kalish, and upon work in musical theatre, orchestras and the many chamber ensembles that make the Toronto music scene so vibrant graduation was awarded New York State’s Thayer Fellowship for the Arts. Praised by the and exciting. The Toronto Wind Orchestra has given Toronto premières of at least a dozen major works, and revived NORTHERN WINDS Globe and Mail for his “effortless virtuosity” in contemporary music, he has given the performance of several masterpieces. Since its inception, Canadian music has been central to Toronto Wind premières of dozens of new pieces, and collaborated with many composers from around Orchestra programming. Over the past dozen years, Toronto Wind Orchestra concerts have included Canadian wind the world, including Anne Boyd, Andrew Ford, Elliott Gyger, Matthew Hindson, Peter ensemble pieces such as Allan Bell’s From a Chaos to the Birth of a Dancing Star, Phil Nimmons’ Riverscape, Messiaen • Applebaum • Colgrass Sculthorpe and Ian Shanahan (Australia), Daniel Koontz, Eric Moe, Ralph Shapey and Michael Colgrass’ Old Churches, Oscar Peterson’s Place St. -

1961-62 Year Book Canadian Motion Picture Industry

e&xri-i METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYERtl WITH THESE CURRENT AMD CANADIAN OPENING! TORO NTO—October 2t UNIVERSITY THEATRE MONTREAL—November 2 ALOUETTE THEATRE Metro-Golduyn-Mayer present. VANCOUVER-Dec. 21 Samuel Bronston's Proaua STANLEY THEATRE IRAMA TECHNICOLOR JEFFREY HUNTER'■ SIOBHAN McKENNA • HURD HATFIELD-RON RANDELL • VIVECA LINDFORS-RITA GAM • CARMEN SEVILLA • BRIGID BAZLEN HARRY GUARDINO • RIP TORN • FRANK THRING • GUY ROLFE • MAURICE MARSAC • GREGOIRE ASLAN • ROBERT RYAN^n,^. Screen Play by PHILIP YORDAN * Directed by NICHOLAS RAY • Produced by SAMUEL BRONSTON METRO GOLDWYN MAYER PRESENTS METRO GOLDWYN MAYER presents a JULIAN BLAUSTEIN production <cMy\KMFY HI</\NI)C) Starring AS FLETCHER CHRISTIAN ri<i-\OR Howard GLENN FORD AS CAPTAIN BUGH INGRID THULIN CHARLES BOYER RICHARD HARRIS AS JOHN mills IN AN ARCOLA PRODUCTION LEE J. COBB PAUL HENREID co starring QMUTluvy qjvT ui'HTt BcyujViy PAUL LUKAS YVETTE MIMIEUX KARL BOEHN co-sTunim HUGH GRIFFITH RICHARD HAYDN »»»TARITA screen play by ROBERT ARDREY and JOHN GAY BASED ON THf NOVEL BVCHARLES NOROHOff AND JAMS S NORMIN HAH based on the novel by directed by omcnm.LEWIS MILESTONE PRODUCE 0 BY AARON ROSENBERG VICENTE BLASCO IBANEZ • VINCENTE MINNELLI TECHNICOLOR • FILMED IN ULTRA PANAVISION in CINEMASCOPE and METROCOLOR 19 CONTINUES ITS SUCCESS STORY COMING BOX-OFFICE ATTRACTIONS! BRIDGE TO THE SUN BACHELOR IN PARADISE CARROLL BAKER, James Shigeta, BOB HOPE, LANA TURNER, James Yagi, Emi Florence Hirsch, Janis Paige, Jim Hutton, Paula Prentiss, Nori Elizabeth Hermann. Don Porter, Virginia Grey, Agnes Moorehead. A Cite Films Production. A Ted Richmond Production. ★ In CinemaScope and Metrocolor SWEET BIRD OF YOUTH ★ PAUL NEWMAN, GERALDINE PAGE, TWO WEEKS IN ANOTHER TOWN Shirley Knight, Ed Begley, Rip Torn, KIRK DOUGLAS, Mildred Dunnock. -

THE CONTRAPUNTAL STYLE of HEALEY WILLAN by WILLIAM

THE CONTRAPUNTAL STYLE OF HEALEY WILLAN by WILLIAM JONATHAN MICHAEL RENWICK .Mus., The University of British Columbia, 19 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming .to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 1982 © William Jonathan Michael Renwick, 1982 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of .Music The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date March 19, 1982 Abstract Healey Willan was a Canadian composer who succeed• ed in integrating a broad range of stylistic character• istics into a personal musical idiom. It is the object of this paper to examine various elements which make up the unique style of this composer, so as to provide a foundation for a better appreciation of the value of his work. The first chapter deals with the varied influences on the composer's development, . and outlines the dif• ferent styles which affected his work. A discussion of his pedagogical methods illustrates that his teaching bears a close relation to his compositional work. -

Orchestral Music of the Canadian Centennial

! ! ORCHESTRAL MUSIC OF THE! CANADIAN CENTENNIAL ! ! ! ! ! ! Isaac !Page ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF! MUSIC May 2020 ! Committee: Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor Per Broman ! !ii ! ABSTRACT ! Emily Freeman Brown, Advisor ! In 1967, Canada celebrated its centennial anniversary of confederation. Celebrations were marked with many significant events in the decade leading up to the centennial, notably the adoption of a new Canadian flag, the construction of many cultural landmarks across the country, and Expo 67 in Montreal. In addition to these major cultural celebrations, there was a noticeable push to create and promote Canadian art. Approximately 130 compositions were written for the centennial year, with many commissions coming from Centennial Commission grants as well as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Of those works, 51 were orchestral compositions that were intended to be performed by orchestras across the country. These works form an important collection that is ripe for study into compositional trends of the time. I believe that composers, writing for such a significant cultural event in Canada, attempted, consciously or not, to codify a Canadian musical identity. I will look into whether shared compositional traits could be considered signifiers of a general Canadian style by looking at previous scholarship on Canadian identity and how it can relate to music. Specific works will be analyzed by Applebaum, Eckhardt-Gramatté, Freedman, Glick, Hétu, Morel, Surdin, and Weinzweig. !iii ! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ! Thank you to my parents, Carolyn Ricketts and Steven Page. I am very aware that I would likely not be where I am, and able to write a document like this, if both of my parents had not been musicians and had not continued to encourage me through my education. -

John Weinzweig and the Canadian Mediascape, 1941-1948

John Weinzweig and the Canadian Mediascape, 1941-1948 by Erin Elizabeth Scheffer A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Erin Elizabeth Scheffer 2019 John Weinzweig and the Canadian Mediascape Erin Elizabeth Scheffer Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2019 Abstract This dissertation explores John Weinzweig’s incidental music for radio and film and its context in Canadian cultural life. Between 1941 and 1948, Weinzweig composed music for nearly one hundred CBC radio docudrama episodes and for four National Film Board documentaries. Weinzweig’s time at the CBC and NFB was his first large scale success as a working composer, following his graduate studies at the Eastman School of Music. Weinzweig’s incidental music was publicly broadcast across Canada, and can be interpreted in light of how it represents Canada during an anxious and difficult yet significant time in the nation’s history through the Second World War and the immediate post-war era. These works, featuring new music broadcast by organizations in their infancy, helped to shape audience perceptions of a rapidly changing country. I begin by situating Weinzweig’s documentary music both temporally and philosophically. The opening chapter explores his biography, the musical context of the 1940s in Canada, and the creation of the CBC and NFB, and it closes by discussing significant themes in the works: indigeneity, northernness, dominion over the landscape, and nation and national affect. The subsequent three chapters divide Weinzweig’s docudramas and documentaries by topic: World War Two propaganda and postwar reconstruction, Canada’s north, and finally a discussion of Weinzweig’s only radio drama The Great Flood , which premiered on CBC’s ii cultural program Wednesday Night in 1948. -

Translation Quality Assessment

Voices and Silences: Exploring English and French Versions at the National Film Board of Canada, 1939-1974 Christine York Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy degree in Translation Studies School of Translation and Interpretation University of Ottawa © Christine York, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 Table of Contents Chapter One: Understanding NFB versions as a site of competing voices ................................................... 1 1.1 Interwoven threads of English and French production ........................................................................ 3 1.2 Defining a corpus ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.3 Defining concepts: Beyond source and target text ............................................................................ 11 1.4 Literature review: NFB ..................................................................................................................... 19 1.5 Literature review: Translation studies ............................................................................................... 25 1.6 Considering multiple voices .............................................................................................................. 32 1.6.1 Voice-over in film studies and audiovisual translation .................................................................. 33 1.6.2 Voice of the text ............................................................................................................................ -

Canadian Production Companies Past and Present, Including Subsidiaries of U.S

Canadian Production Companies Past and Present, Including Subsidiaries of U.S. and other Foreign-based Companies ©2006-2007 Marsha Ann Tate Last updated: February 20, 2007 @ 9:46 a.m. The following is a list of Canadian film and television production companies compiled from a variety of yearbooks, directories, and other sources published between the 1950s and February 2007. Updates to the list will be made periodically. Comments or suggestions? Please contact: Marsha Ann Tate, 222 Buckhout Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802, Phone: 814-865-7736, Email: [email protected] A AAC Fact (Toronto, Ontario) Fact-based/documentary production arm of Alliance Atlantis Communications AAC Kids (Toronto, Ontario) Children's programming-focused production arm of Alliance Atlantis Communications ABC Films of Canada Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) Able Editing & Service Ltd. (Edmonton, Alberta) Production and distribution company. ABS Productions (Halifax, Nova Scotia) Academy TV Film Productions of Canada (Toronto, Ontario) Producers of industrial and commercial films. Accent Entertainment Corporation (Toronto, Ontario) Company specializes in the production of feature films; movies-of-the-week and series. Adam Productions Ltd. (Vancouver, British Columbia) Adaptel Productions (Montreal, Quebec) Production and distribution company. Orly Adelson Productions (United States) A.C.P.A.V. (Montreal, Quebec) Production and distribution company. ADS Film Productions (Toronto, Ontario) Production and distribution company. Canadian Production Companies Past and Present, rev. February 20, 2007, Marsha Ann Tate 2 Advertel Productions Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) Manager: O. Collier Agincourt Productions Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) Agravoice Productions Ltd. (Edmonton, Alberta) A.K.A. Cartoon (Vancouver, British Columbia) AKO Productions Ltd. (Toronto, Ontario) President: A. Kenneth Orton Secretary: Ian R. -

Canadian Music Council

CANADIAN MUSIC COUNCIL CONSEIL CANADIEN DE LA MUSIQUE MUS 153 Prepared by : John L. Tung Date : April 20, 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Box Index ...................................................... ii List of abbreviations used .......................................... v Restricted documents.............................................ix CONSTITUTION AND HISTORY 1.1 Constitution ............................................... 2 1.2 History................................................... 2 BOARD OFFICE 2.1 Board office and special meetings .............................. 6 2.2 Board of directors .......................................... 9 2.3 Board office correspondence ................................. 10 MEETINGS OF THE CANADIAN MUSIC COUNCIL 3.1 Annual meetings .......................................... 13 3.2 President's annual meetings ................................. 16 3.3 Correspondence re annual meeting ............................ 16 CONFERENCE OF THE CANADIAN MUSIC COUNCIL 4.1 Conference organization .................................... 18 4.2 Conference documents..................................... 22 4.3 Conference papers ........................................ 26 4.4 Panels .................................................. 32 4.5 Conference's financial statements ........................ 34 4.6 General correspondence .................................... 39 4.7 Publication of annual conference .............................. 46 4.8 Miscellaneous ............................................ 48 MEMBERSHIP 5.1 Board members.......................................... -

FONDS LEVEL DESCRIPTION Title: Louis Applebaum Fonds Dates

Louis Applebaum fonds Inventory #254 Page 1 FONDS LEVEL DESCRIPTION Title: Louis Applebaum fonds Dates: 1931-2000 Extent: 34.2 m of textual records ca. 590 photographs; 50 negatives; 1 contact sheet ca. 330 audio tapes; 240 audio cassettes; 360 phonographs; 1 compact disc; 1 CD-ROM, 2 DATs ca. 25 film reels; 40 video tapes 2 architectural drawings; 1 stamp Biographical Sketch: Louis Applebaum (1918-2000) was a composer, conductor, and arts administrator. He was born and educated in Toronto, except for one year studying in New York with Roy Harris and Bernard Wagenaar. His career in film began in 1940, composing scores for the National Film Board of Canada, later becoming its Music Director. His over 200 film scores included productions in Canada, Hollywood, England and New York and were awarded many honours such as an Academy Award nomination (The Story of G.I. Joe, 1945), Canadian Film Award, Genie and Gemini. Applebaum was the first Music Director of the Stratford Festival and composed scores for over 70 of its plays. He founded and operated its Music and Film Festivals and conducted operas at Stratford and on tour. His fanfares have introduced every Festival theatre performance since opening night in 1953. Scores for radio, TV series and specials, numbering in the hundreds, have been heard on the CBC, CTV, BBC, CBS, NBC, and United Nations radio. His concert works in all genres have been widely performed throughout the world and include large works for symphony, ballet and the music stage. His commissions for ceremonial occasions include the inauguration of three Governors-General, the opening of Expo 67 in Montreal and visits by the Queen.