Viewed the Thesis/Dissertation in Its Final Electronic Format and Certify That It Is an Accurate Copy of the Document Reviewed and Approved by the Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

UBC High Notes Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia

UBC High Notes Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia Fall 2012 Director’s Welcome Welcome to the fourteenth edition of High Notes, celebrating the recent activities and major achievements of the faculty and students in the UBC School of Music! I think you will find the diversity and quality of accomplishments impressive and inspiring. A major highlight for me this year is the opportunity to welcome three exciting new full-time faculty members. Pianist Mark Anderson, with an outstanding international reputation gave a brilliant first recital at the School in October.Jonathan Girard, our new Director of the UBC Symphony Orchestra, and Assistant Professor of Conducting, led the UBC Symphony Orchestra in a full house of delighted audience members at the Chan Centre on November 9th. Musicologist Hedy Law, a specialist in 18th-century French opera and ballet is, has already established herself well with students and faculty in the less public sphere of our academic activities. See page 4 to meet these new faculty members who are bringing wonderful new artistic and scholarly energies to the School. It is exciting to see the School evolve through its faculty members! Our many accomplished part-time instructors are also vital to the success and profile of the School. This year we welcome to our team several UBC music alumni who have won acclaim as artists and praise as educators: cellist John Friesen, composer Jocelyn Morlock, film and television composer Hal Beckett, and composer-critic-educator David Duke. They embody the success of our programs, and the impact of the UBC School of Music on the artistic life of our province and nation. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Filumena and the Canadian Identity a Research Into the Essence of Canadian Opera

Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final thesis for the Bmus-program Icelandic Academy of the Arts Music department May 2020 Filumena and The Canadian Identity A Research into the Essence of Canadian Opera Alexandria Scout Parks Final Thesis for the Bmus-program Supervisor: Atli Ingólfsson Music Department May 2020 This thesis is a 6 ECTS final thesis for the B.Mus program. You may not copy this thesis in any way without consent from the author. Abstract In this thesis I sought to identify the essence of Canadian opera and to explore how the opera Filumena exemplifies that essence. My goal was to first establish what is unique about Canadian opera. To do this, I started by looking into the history of opera composition and performance in Canada. By tracing these two interlocking histories, I was able to gather a sense of the major bodies of work within the Canadian opera repertoire. I was, as well, able to deeper understand the evolution, and at some points, stagnation of Canadian opera by examining major contributing factors within this history. My next steps were to identify trends that arose within the history of opera composition in Canada. A closer look at many of the major works allowed me to see the similarities in terms of things such as subject matter. An important trend that I intend to explain further is the use of Canadian subject matter as the basis of the operas’ narratives. This telling of Canadian stories is one aspect unique to Canadian opera. -

Piano Manufacturing an Art and a Craft

Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Gesa Lücker (Concert pianist and professor of piano, University for Music and Drama, Hannover) Nikolaus W. Schimmel Piano Manufacturing An Art and a Craft Since time immemorial, music has accompanied mankind. The earliest instrumentological finds date back 50,000 years. The first known musical instrument with fibers under ten sion serving as strings and a resonator is the stick zither. From this small beginning, a vast array of plucked and struck stringed instruments evolved, eventually resulting in the first stringed keyboard instruments. With the invention of the hammer harpsichord (gravi cembalo col piano e forte, “harpsichord with piano and forte”, i.e. with the capability of dynamic modulation) in Italy by Bartolomeo Cristofori toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, the pianoforte was born, which over the following centuries evolved into the most versitile and widely disseminated musical instrument of all time. This was possible only in the context of the high level of devel- opment of artistry and craftsmanship worldwide, particu- larly in the German-speaking part of Europe. Since 1885, the Schimmel family has belonged to a circle of German manufacturers preserving the traditional art and craft of piano building, advancing it to ever greater perfection. Today Schimmel ranks first among the resident German piano manufacturers still owned and operated by Contents the original founding family, now in its fourth generation. Schimmel pianos enjoy an excellent reputation worldwide. 09 The Fascination of the Piano This booklet, now in its completely revised and 15 The Evolution of the Piano up dated eighth edition, was first published in 1985 on The Origin of Music and Stringed Instruments the occa sion of the centennial of Wilhelm Schimmel, 18 Early Stringed Instruments – Plucked Wood Pianofortefa brik GmbH. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Bolderboulder 10K Results

BolderBOULDER 1986 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Jon Luff M18 31:14 Jeff Sanchez M20 31:23 Jonathan Hume M18 31:58 Ed Ostrovich M27 32:04 Mark Stromberg M21 32:09 Michael Velasquez M16 32:21 Rick Renfrom M32 32:22 James Ysebaert M22 32:24 Louis Anderson M32 32:25 Joel Thompson M27 32:27 Kevin Collins M31 32:34 Rob Welo M22 32:42 Bill Lawrance M31 32:44 Richard Bishop M28 32:45 Chester Carl M33 32:47 Bob Fink M29 32:51 David Couture M18 32:54 Brent Terry M24 32:58 Chris Nelson M16 33:02 Robert III Hillgrove M18 33:05 Steve Smith M16 33:08 Rick Katz M37 33:11 Tom Donohoue M30 33:14 Dale Garland M28 33:17 Michael Tobin M22 33:18 Craig Marshall M28 33:20 Mark Weeks M34 33:21 Sam Wolfe M27 33:23 William Levine M25 33:26 Robert Jr Dominguez M30 33:26 David Teague M32 33:28 Alex Accetta M16 33:29 Dave Dreikosen M32 33:31 Peter Boes M22 33:32 Daniel Bieser M24 33:32 Matt Strand M18 33:33 George Frushour M23 33:34 Everett Bear M16 33:35 Bruce Pulford M31 33:36 Jeff Stein M26 33:40 Thomas Teschner M22 33:42 Mike Chase M28 33:43 Michael Junig M21 33:43 Parrick Carrigan M26 33:44 Jay Kirksey M30 33:46 Todd Moore M22 33:49 Jerry Duckworth M24 33:49 Rick Reimer M37 33:50 RaY Keogh M28 33:50 Dave Dooley M39 33:50 Roger Innes M26 33:50 David Chipman M22 33:51 Brian Boehm M17 33:51 Michael Dunlap M29 33:51 Arthur Mizzi M30 33:52 Jim Tanner M18 33:52 Bob Hillgrove M41 33:52 Ramon Duran M18 33:52 Ken Jr. -

Saison 2013/2014 Grußwort

Saison 2013/2014 Grußwort Liebe Musikfreunde, liebe Konzertbesucher, unsere Konzertreihe im Von-Busch-Hof gibt es nun schon mehr als zehn Jahre. Wir freuen uns über den hohen Bekannt- heitsgrad der Konzertreihe weit über die engere Region hinaus. In jeder Saison ist es uns gelungen, mit erstklassigen Künstlern beeindruckende Konzerte zu veranstalten. Von Anfang an spielte Kammermusik eine wichtige Rolle: Unsere Besucher konnten immer wieder faszinierend schöne klassische Musik erleben. Mit Schuberts “Forellenquintett” und dem Liederzyklus “Die Winterreise” erklingen in dieser Saison zwei der bekanntesten Werke der klassischen Musik. Aber auch für das Amüsement in der Neujahrsgala beim Hören und Wiedererkennen von beliebten Schlagern und von brillant gespielter Filmmusik des letzten Jahrhunderts schwärmen viele. Das fabelhafte Schellack-Orchester mit seinen Solisten entfes- selt dabei jedesmal Beifallsstürme. Interessante Kinderkonzerte, eines im November, das andere im Februar, fehlen auch in dieser Saison natürlich nicht. Ganz sicher werden Joseph Moog am Klavier und das Busch- Hof Consort im abschließenden Open Air Konzert der Saison mit der Darbietung von drei Klavierkonzerten einen triumpha- len Schlusspunkt setzen. Die gute Akustik im Saal und im Innenhof, dazu das stilvolle und behagliche Ambiente des Von-Busch-Hofs wird von vielen Besuchern gerühmt und ist eine angenehme und erfreuliche Beigabe zu den Konzerten. Künstler, die bei uns auftreten, sind immer wieder angetan von dem charmanten Veranstaltungsort, aber in demselben Maße auch von dem interessierten und aufmerksamen Publikum. Wir sind stolz auf das Erreichte. Unser Bestreben ist, auch in Zukunft unsere Zuhörerschaft mit einem anspruchsvollen Programm zu begeistern. Wir wünschen Ihnen schöne und erquickliche Stunden im Von-Busch-Hof. -

Creating Timeless Classics

PENTATONE LIMITED CREATING TIMELESS CLASSICS Sit back and enjoy Creating timeless classics Around the start of the new suffering. But PENTATONE’s founders For all their diversity, the artists We don’t dabble in technology for millennium, three music enthusiasts were unwilling to compromise their featured on PENTATONE have one technology’s sake – we believe it’s came together to launch a new vision, so convinced were they of the thing in common. They all put their the only way to truly appreciate music label that promised to new technology that they launched heart and soul into the music, these great works of art. redefine the way people listen to their own label in 2001. drawing on every last drop of classical music. creativity, skill, and determination As we celebrate 13 years of After a somewhat rocky start, to perfect their compositions. PENTATONE and prepare for a Their vision was crystal clear: to the label quickly began adding changing of the guard, it is time to offer an unrivalled classical music talented artists to its roster. Now, PENTATONE exists to extract reflect on our achievements and experience through superior audio 13 years later, PENTATONE enjoys everything that went into creating look toward the future. technology. a reputation for excellence, its these timeless classics and put it catalogue comprising some of the before the listener with a resolution This release – the first to feature The introduction of 5-channel very best that classical music has to and crispness not found anywhere the label’s new visual identity – surround sound which made this offer. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: a QUESTION of NATIONALISM a Thesis Submitted in Partial Satis

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE CANADIAN MUSIC SINCE 1940: A QUESTION OF NATIONALISM A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Ronald Frederick Erin August, 1983 J:lhe Thesis of Ronald Frederick Erin is approved: California StD. te Universi tJr, Northridge ii PREFACE This thesis represents a survey of Canadian music since 1940 within the conceptual framework of 'nationalism'. By this selec- tive approach, it does not represent a conclusive view of Canadian music nor does this paper wish to ascribe national priorities more importance than is due. However, Canada has a unique relationship to the question of nationalism. All the arts, including music, have shared in the convolutions of national identity. The rela- tionship between music and nationalism takes on great significance in a country that has claimed cultural independence only in the last 40 years. Therefore, witnessed by Canadian critical res- ponse, the question of national identity in music has become an important factor. \ In utilizing a national focus, I have attempted to give a progressive, accumulative direction to the six chapters covered in this discussion. At the same time, I have attempted to make each chapter self-contained, in order to increase the paper's effective- ness as a reference tool. If the reader wishes to refer back to information on the CBC's CRI-SM record label or the Canadian League of Composers, this informati6n will be found in Chapter IV. Simi- larly, work employing Indian texts will be found in Chapter V. Therefore, a certain amount of redundancy is unavoidable when interconnecting various components. -

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity 2 Copyright © Sarah Thornton 1995 The right of Sarah Thornton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1995 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Reprinted 1996, 1997, 2001 Transferred to digital print 2003 Editorial office: Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Marketing and production: Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF, UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any 3 form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN: 978-0-7456-6880-2 (Multi-user ebook) A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Palatino by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in Great Britain by Marston Lindsay Ross International -

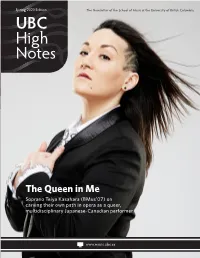

Spring 2020 Edition the Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia UBC High Notes

Spring 2020 Edition The Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia UBC High Notes The Queen in Me Soprano Teiya Kasahara (BMus’07) on carving their own path in opera as a queer, multidisciplinary Japanese-Canadian performer www.music.ubc.ca SPOTLIGHT LIBERATING THE QUEEN IN ME Photo: Takumi Hayashi/UBC In their new play The Queen in Me, soprano Teiya Kasahara (BMus’07) liberates one of opera’s most iconic villains — and challenges the industry’s centuries-old prejudices Photo: Tallulah By Tze Liew In The Queen in Me, the Queen of the Night at age 15, after seeing Ingmar Bergman’s film begins to sing her most iconic aria, “Der Hölle version of The Magic Flute. “I saw her perform For more than two centuries, the iconic Queen Rache,” like she would in any Magic Flute show. and was like, Oh God, I want to do that,” they of the Night from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte But midway through, she halts. “Stopp! Stopp remember. has been thrilling audiences with her vengeful die Musik!” she screams. Breaking the fourth spirit, bloodthirsty drive, and volatile high Fs. wall, she laments the stifling act everyone’s With this as their dream role, Kasahara dove Qualities that make her the ultimate villain, come to see; one she’s been trapped in for headfirst into voice training, made it into fated to eternal doom while the hero and over two centuries. the UBC Opera program, and honed their heroine, demure as lambs, skip off to enjoy craft for four years under the tutelage of their happy ending.