Latgalia in Mnemohistory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

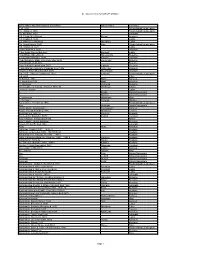

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

Path Dependency and Landscape Biographies in Latgale, Latvia: a Comparative Analysis

Europ. Countrys. · 3· 2010 · p. 151-168 DOI: 10.2478/v10091-010-0011-7 European Countryside MENDELU PATH DEPENDENCY AND LANDSCAPE BIOGRAPHIES IN LATGALE, LATVIA: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS Anita Zarina1 Received 30 September 2010; Accepted 15 October 2010 Abstract: This paper focuses on the path dependency of landscapes in Latgale, Latvia from the present perspective at the regional and local scale. During the last centuries Latvia’s landscapes have passed through radical changes, which were driven by political events. Each new political era discarded the ideas of the previous era and subsequently reorganized the land(scape) according to the new views. At the regional level the role of history is significant in analyzing landscapes while at the local level the main force is people, often themselves not knowing the history of the place but putting the existing path dependency into practise or disregarding it. The biographies of two former villages are discussed: one which is nearly deserted but filled with forgotten or neglected cultural heritage values and the other – alive and interwoven with some old (almost forgotten) cultural practises. Path dependency in landscapes is relevant only regarding the attachment of people to a place and the experience on which their further desires are based. Key words: Landscape biographies, landscape change, Latgale, path dependency Rezumējums: Raksta pamatā ir pēctecīguma (path dependence) izpausmes Latgales ainavā reģionālā un lokālā mērogā no šodienas skatupunkta. Pēdējo gadsimtu laikā Latvijā ir notikušas dramatiskas ainavas pārmaiņas, to galvenie rosinātāji – politisko varu maiņas. Katra jaunā politiskā ēra veidoja jaunas ainavas saskaņā ar tās ideoloģiju un idejām. Rakstā tiek diskutēts, ka reģionāla mēroga ainavas studijas ir cieši saistītas ar vēstures izpratni un tās lomu, kamēr lokālā mērogā galvenie ainavas veidotāji ir cilvēki un to darbības, kuri bieži vien pat neapzinās vietas/reģiona vēsturi, bet praktizē vai ignorē daudzas paražas vai telpiskās struktūras pēctecības ainavā. -

Riga Municipality Annual Report 2018

Riga, 2019 CONTENT Report of Riga City Council Chairman .................................................................................................................... 4 Report of Riga City Council Finance Department Director ................................................................................... 5 Riga Municipality state ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Riga City population.............................................................................................................................................. 6 Riga Municipality economic state.......................................................................................................................... 7 Riga Municipality administration structure, functions, personnel........................................................................... 9 Riga Municipality property state .............................................................................................................................. 11 Value of Riga Municipal equity capital and its anticipated changes...................................................................... 11 Riga Municipality real estate property state........................................................................................................... 11 Execution of territory development plan ............................................................................................................... -

Iveta Apkalna Orgue Gábor Boldoczki Trompette Autour De L'orgue

Autour de l’orgue Mercredi / Mittwoch / Wednesday 22.04.2015 20:00 Grand Auditorium Iveta Apkalna orgue Gábor Boldoczki trompette Johann Gottfried Müthel (1728–1788) Fantasie F-Dur (fa majeur) für Orgel – 6’ Jean-Baptiste Loeillet (1680–1730) Sonate pour trompette et orgue en si bémol majeur (B-Dur) (d’après / nach: Sonate pour flûte à bec et basse continue en ut majeur (C-Dur) op. 3/1) (1715) – 8’ Adagio – Presto – Adagio – Presto – Largo Vivace Adagio Allegro – Adagio – Allegro Paul Hindemith (1895–1963) Sonate für Orgel N° 1 (1937) – 18’ Mäßig schnell – Lebhaft Sehr langsam Phantasie: Frei Ruhig bewegt Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1751) Concerto pour trompette et orgue en mi bémol majeur (Es-Dur) «San Marco» (d’après / nach: Sonate pour violon et basse continue op. 6 N° 11) (arr. Jean Thilde) (–1712) – 8’ Grave Allegro Adagio Allegro — Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Präludium und Fuge D-Dur (ré majeur) BWV 532 für Orgel (~1708–1717) – 12’ Präludium – Alla breve – Adagio Fuge George Enescu (1881–1955) Légende pour trompette et piano (arr. pour trompette et orgue) (1906) – 6’ Thierry Escaich (1965) Deux Évocations pour orgue (1996) – 15’ Georg Friedrich Händel (1685–1759) Suite für Trompete und Orchester D-Dur (ré majeur) HWV 341 «Water Piece» (arr. für Trompete und Orgel) (–1733) – 8’ Ouverture Allegro (Gigue) Air (Minuet) March (Bourée) March Mille et un éclats de métal… Œuvres pour trompette et orgue Hélène Pierrakos Müthel: Fantasie en fa majeur pour orgue Musicien à peu près contemporain du dernier fils de Bach, Jo- hann Gottfried Müthel devient organiste et claveciniste à la cour du duc Karl-Ludwig II von Mecklenburg-Schwerin. -

Latvia Since 1918

Latvia since 1918 The Wolfgang Watzke Collection Latvia‘s Freedom Monument in Riga 10 LATVIA SINCE 1918 6006 / € 150 6007 / € 80 ex 6008 / € 80 6005 / € 100 ex 6004 / € 100 Detail 6009 / € 120 Detail 6010 / € 120 Detail 6012 / € 150 Detail 6011 / € 150 Detail 6013 / € 150 LATVIA SINCE 1918 11 LatVIA Lot-No. Mi.-No. Western Army Start price 6001 0/1 1919, unused/ mint never hinged and used collection with some covers including Mi.-Nr. /6/4 1-11 (without 10k.) on two covers, later issue also with multiples, gutter pairs etc., in addition some forgeries, many signed Davydoff, Hoffmann, Rucins etc., (Photo = 1 www) 300 Latvia - Issued Stamps 6002 6003 6002 1918, Women with ears of corn on their arms in front of the rising sun 5 k., black ink drawing, partly touched up with opaque white, on thin carton (104x147mm), signed on reverse, a very attractive item, unique 200 6003 Acorn branch and Corn bundle in front of the rising sun 20 k., black ink drawing, partly touched up with opaque white, on thin carton (102x147mm), signed on reverse, a very attractive item, unique 200 6004 1P 2 Sun pattern 5 k. black on map and vertical pair carmine printed on map side, without gum, the pair light bend, otherwise fine (Photo = 1 10) 100 6005 1P 1 5 k. orange as colour proof on map paper, mint never hinged, fine (Photo = 1 10) 100 6006 1 4/2 5 k. carmine, block of four printed on both sides, without gum, fine (Photo = 1 10) 150 6007 1 2 5 k. -

Kruk Latvia Statues

Conference on the Historical Use of Images Vrije Universiteit Brussel, 10-11 March 2009 Wars of Statues: Ius imaginum and Damnatio memoriae in the 20th century Latvia. Sergei Kruk In Latvia outdoor sculpture functions as a medium of political communication. Transformations of political regime engendered the alteration of representation politics aimed at attesting the new power relations. Not always the authorities can topple down a monument and erect a new one to propagate an unambiguous political message. More subtle methods are exploited to depreciate the unwanted sculptures and to break in the public sphere with new political messages. This paper conceptualises the peculiarities of this kind of political communication in semiotic terms. Among the most popular practices are renaming of monuments, change or addition of inscriptions, circulation of new explanations, permitting of natural decay and banal vandalism, modification of environment around the sculpture, and its inclusion in rituals. Outdoor sculpture as a medium of political communication Latvia has experienced several waves of erection and destruction of monuments in the 20th century. The change of representation practice coincided with the political transformations in the state. As a part of the memory rewriting project, ostensibly the commemoration of persons and events asserted the regime change and legitimised the power relations. Sculpture’s peculiar role in political communication owes to the treatment of visual icon in Russian and Latvian cultural tradition. Roman legal terms ius imaginum and damnatio memoriae are used in the title to highlight that the controversy over outdoor sculpture has deep roots in the millennia long debate on visual iconicity. -

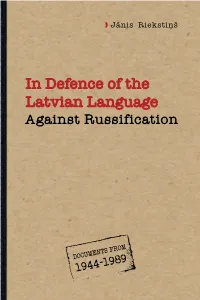

In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification. Documents from 1944-1989

the Jānis Riekstiņš of Language Defence In Latvian Against Russification Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification The Latvian Language Agency Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification Riga Latviešu valodas aģentūra / The Latvian Language Agency 2012 UDK 811.174’ 272(474.3)(093) De 167 Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification 1944–1989 Documents In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification. 1944–1989. Documents. Compiled and translated from the Russian by J. Riekstiņš. Introduction by Prof. Uldis Ozoliņš, foreword by J. Riekstiņš. Managing editor D. Liepa. Riga: LVA, 2012. 160 pages. Managing editor Dr. Dite Liepa Literary editor P. Cedriņš Reviewer Dr. Dzintra Hirša Documents utilized are from the Latvian State Archive collection of LCP CC records (PA-101. fonds), LCP Central Control and Auditing Committee (PA-2160), the LSSR Council of Ministers (270. fonds), LSSR Supreme Council (290. fonds), the Riga City Executive Committee (1400. fonds), as well as documents from collections of other institutions, that verify the Soviet policies in Latvian SSR. Many of these documents are published for the first time. Cover design and layout: Vanda Voiciša © LVA, 2012 © Jānis Riekstiņš, compiler, translator from the Russian language, foreword author © Uldis Ozoliņš, foreword author © Vanda Voiciša, “Idea lex”, cover design and layout ISBN 978-9984-815-77-0 Table of Contents Introduction: the struggle for the status of the Latvian language during the Soviet occupation 1944 to 1989 ............ 6 Foreword by J. Riekstiņš ........................................18 Section 1 Decisions and materials on the acquisition of the Latvian language .........................21 Section 2 Decisions on learning Russian. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

EIROPAS KULTŪRAS GALVASPILSĒTA EUROPEAN CAPITAL of CULTURE Juriskalniņš / Fotocentrs

ENG EIROPAS KULTŪRAS GALVASPILSĒTA EUROPEAN CAPITAL OF CULTURE Juris Kalniņš / Fotocentrs. Bird’s-eye view of Rīga Experience the Force Majeure of Culture! Rīga takes its visitors by surprise with its will introduce you to the most extensive and most Umeå 2014 external beauty as well as its rich world of interiors. significant activities of the European Capital of If you have never been to Rīga before, now is the Culture programme – and remember, whichever of time to experience the pleasure of discovering the them you choose to attend, be open-minded and diversity of Latvia’s capital city. Ancient and at the prepared to experience the unexpected! same time youthful, European and multicultural, today’s Rīga is the place to recharge your cultural Diāna Čivle, batteries. Head of the Rīga 2014 Foundation Rīga 2014 After you get to know the medieval streets of the Old Town, the Art Nouveau heritage and the shabby chic of the creative quarters, let us surprise you Kosice 2013 once more – this time with the saturated content Welcome to Maribor 2012 of Rīga’s cultural events calendar for the whole of Marseille 2013 2014. EsplanādE 2014! It is the surprising, the unexpected and even the Guimarães 2012 provocative that underpin the Force Majeure cultural The end of June will see a new building rise in programme of the European Capital of Culture. It the very heart of Rīga, between the Nativity of is the creative power that cannot be foreseen or Christ Orthodox Cathedral and the monument to planned beforehand. The miracle happens and the poet Rainis in the Esplanāde Park. -

Evidence of the Reformation and Confessionalization Period in Livonian Art

Ojārs Spārītis EVIDENCE OF THE REFORMATION AND CONFESSIONALIZATION PerIOD IN LIVONIAN ArT INTRODUCTION The singular transitional period that led from the slowly evolving me- dieval vision of the world to a new perception of life with its dynamic expression in works of history and art history texts has been given labels that reflect its chronological evolution, as well as the epithets referring to its philosophical and aesthetic content. To illustrate the variety of the social and spiritual aspects of European spiritual life in the second half of the 15th and the 16th century, literature in the humanitarian spheres exploited concepts from the Renaissance, the Reformation and Counter- Reformation. Concepts of both humanism and hedonism were used to characterize the domestic cultural content and form. However, they fail to reveal the development of the new historical period and contradic- tion-rich diversity of the material and spiritual life in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the growing dominance of economic expansion and the endeavours to acquire new knowledge along with the awareness of the tangible benefits and spiritual advantages of a university education was so characteristic of European culture. The history of spiritual evolution, with the variations related to the Reformation and confessionalization, is characterised by local regional contexts and forms of expression, but it also has a mandatory syn- chronicity with the processes of European political and intellectual life. Looking forward to the 500th anniversary of the Reformation initi- DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/BJAH.2015.9.03 24 Ojārs Spārītis Reformation and Confessionalization Period in Livonian Art 25 ated by Martin Luther, it is worth examining the Renaissance-marked – the Teutonic Order and the bishops – used both political and spiritual fine arts testimonies from the central part of the Livonian confedera- methods in their battle for economic power in Riga. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

Baltic Vintage and Classic Car Rally 2014 – LATVIA – ESTONIA – Th Th Tuesday, June 24 – Tuesday, July 01 2014

The “Baltic Classic and Vintage Car Rally 2014” is a well organized rally tried and tested in 2012 by the 20-Ghost Club, the oldest Rolls Royce club in the world, headed by Sir John Stuttard. Baltic Vintage and Classic Car Rally 2014 – LATVIA – ESTONIA – th th Tuesday, June 24 – Tuesday, July 01 2014 White nights, unspoilt nature, the Baltic sea, medieval cities, stunning landscapes, vibrant Riga, charming Tallinn and participation in 2nd Vihula Manor Vintage and Classic Car Day at the unique Vihula Manor Country Club & Spa ul Program TUESDAY, JUNE 24th – TUESDAY, JULY 1ST 2014 24.06 (Tue), Arrival in Riga Upon individual arrival in Riga we will be accommodated at the 5-star Hotel Radisson Blu Ridzene, built in the 70es as a governmental hotel. After Latvia regained indepen- dence the hotel underwent complete renovation, which gave it a very stylish Scandinavian design. Riga, founded in 1201 by the German bishop Albert, is the largest of the three Baltic capitals and boasts a real kaleidoscope of architectural styles. 14.00-17.00 The afternoon walking tour of the Old Town will acquaint us with all the splendours of medieval Riga including Riga Castle, the Dome Cathedral, St. Peter's Church, St. Jacob's Church, the Swedish Gate, the Three Brothers, the Large and Small Guild Houses and the Powder Tower. In the evening we enjoy a Latvian nouvelle cuisine welcome dinner at the stylish Restaurant La Boheme in Riga's famed Art Nouveau quarter. 25.06 (Wed), Riga – Bauska – Rundale Palace – Jurmala – Riga, 210 km The day is reserved for a day trip to the South of Latvia.