Election Rallies: Performances in Dissent, Identity, Personalities and Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan

Why Are Gender Reforms Adopted in Singapore? Party Pragmatism and Electoral Incentives* Netina Tan Abstract In Singapore, the percentage of elected female politicians rose from 3.8 percent in 1984 to 22.5 percent after the 2015 general election. After years of exclusion, why were gender reforms adopted and how did they lead to more women in political office? Unlike South Korea and Taiwan, this paper shows that in Singapore party pragmatism rather than international diffusion of gender equality norms, feminist lobbying, or rival party pressures drove gender reforms. It is argued that the ruling People’s Action Party’s (PAP) strategic and electoral calculations to maintain hegemonic rule drove its policy u-turn to nominate an average of about 17.6 percent female candidates in the last three elections. Similar to the PAP’s bid to capture women voters in the 1959 elections, it had to alter its patriarchal, conservative image to appeal to the younger, progressive electorate in the 2000s. Additionally, Singapore’s electoral system that includes multi-member constituencies based on plurality party bloc vote rule also makes it easier to include women and diversify the party slate. But despite the strategic and electoral incentives, a gender gap remains. Drawing from a range of public opinion data, this paper explains why traditional gender stereotypes, biased social norms, and unequal family responsibilities may hold women back from full political participation. Keywords: gender reforms, party pragmatism, plurality party bloc vote, multi-member constituencies, ethnic quotas, PAP, Singapore DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5509/2016892369 ____________________ Netina Tan is an assistant professor of political science at McMaster University. -

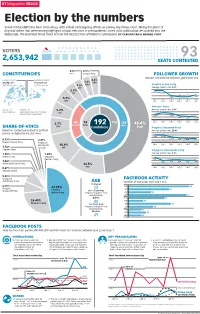

200708 BT Ge2020 in Numbers

BT Infographics GE2020 Election by the numbers Social media platforms have been abuzz with virtual campaigning efforts as polling day draws close, taking the place of physical rallies that were among highlights of past elections in pre-pandemic times. With political parties pushed into the digital age, The Business Times looks at how the GE2020 has unfolded in cyberspace. BY CLAUDIA TAN & NATALIE CHOY VOTERS 93 2,653,942 SEATS CONTESTED 0.5% 0.5% CONSTITUENCIES PPP Independent FOLLOWER GROWTH Number of Facebook followers gained per day Largest GRC Smallest SMC 2.6% Ang Mo Kio Potong Pasir 2.6% SDA 185,465 electors 19,740 electors 2.6% RDU People’s Action Party SPP Average growth rate: 2.3% 3.1% 1,332 RP 1,347 338 338 653 5.2% 516 NSP July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 Workers’ Party GRCs: 17 SMCs: 14 5.2% Average growth rate: 9.5% New: Sengkang New: Kebun Baru, Yio Chu Kang, PV Marymount, Punggol West 2,699 2,098 2,421 1,474 1,271 1,336 July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 5.7% 40 74 118 152 48.4% Female New 192PSP Male SHARE-OF-VOICE SDP Candidates PAP Progress Singapore Party Based on content generated by political Average growth rate: 22.4% parties on digital media platforms 1,539 1,539 1,119 0.19% 2.29% 932 836 776 People’s Power Party Singapore Democratic 10.9% July 1 July 2 July 3 July 4 July 5 July 6 1.72% Alliance WP Peoples Voice Singapore Democratic Party 1.48% 1.60% Average growth rate: 5.6% Reform Party Singapore People’s Party 813 1.46% 498 558 565 503 540 National Solidarity Party 12.5% 0.67% PSP July 1 July 2 -

Major Vote Swing

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 Major vote swing Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang SMC Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Chua Chu Kang Ang Mo Kio Holland- GRC GRC Pasir Ris- Bukit Punggol GRC Hong Kah Timah North SMC GRC Aljunied Tampines Bishan- GRC GRC Toa Payoh East Coast GRC GRC West Coast Marine GRC Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC MacPherson SMC Mountbatten SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jurong GRC Potong Pasir SMC Chua Chu Kang Registered voters: 119,931; Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Jalan Besar total votes cast: 110,191; rejected votes: 2,949 SMC SMC SMC SMC SMC 76.89% 23.11% (84,731 votes) (25,460 votes) PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY (83 SEATS) WORKERS’ PARTY (6 SEATS) PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih SIX-MEMBER GRC Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif Ang Mo Kio Pasir Ris-Punggol 2011 winner: People’s Action Party (61.20%) Registered voters: 187,771; Registered voters: 187,396; total votes cast: 171,826; rejected votes: 4,887 total votes cast: 171,529; rejected votes: 5,310 East Coast Registered voters: 99,118; 78.63% 21.37% 72.89% 27.11% total votes cast: 90,528; rejected votes: 1,008 (135,115 votes) (36,711 votes) (125,021 votes) (46,508 votes) 60.73% 39.27% (54,981 votes) (35,547 votes) PEOPLE’S THE REFORM PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh J Puthucheary Abu Mohamed PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Darryl David Jesse Loo Ng Chee Meng Arthero Lim ACTION PARTY PARTY Gan -

Top 1000 Searches in Google Singapore

Top 1000 Searches in Google Singapore https://www.iconicfreelancer.com/top-1000-google-singapore/ # Keyword Volume 1 youtube 3080000 2 whatsapp web 2570000 3 google 1710000 4 google translate 1570000 5 gmail 1520000 6 facebook 1220000 7 translate 1050000 8 pornhub 978000 9 sls 824000 10 whatsapp 695000 11 netflix 661000 12 cna 658000 13 yahoo 654000 14 dbs ibanking 626000 15 shopee 604000 16 google drive 599000 17 carousell 597000 18 xhamster 543000 19 edmw 537000 20 lazada 502000 21 yahoo mail 466000 22 coronavirus 453000 23 hotmail 439000 24 telegram web 425000 25 us election 407000 26 dbs 406000 27 genshin impact 401000 28 ocbc 387000 29 xvideos 378000 30 xnxx 376000 31 singapore pools 345000 32 usd to sgd 336000 33 amazon 329000 34 instagram 318000 35 roblox 318000 36 cpf 318000 37 google docs 313000 38 straits times 292000 39 mothership 291000 40 linkedin 290000 41 qoo10 289000 42 telegram 274000 43 channel news asia 272000 44 fb 272000 45 speed test 266000 46 uob 261000 47 liverpool 261000 48 mrt map 260000 49 epl 259000 50 youtube to mp3 239000 51 thumbzilla 235000 52 google classroom 230000 53 trump 223000 54 google map 223000 55 singapore news 221000 56 porn 220000 57 discord 219000 58 calculator 218000 59 nba 215000 60 english to chinese 214000 61 thank you coronavirus helpers 212000 62 foodpanda 212000 63 iras 210000 64 spankbang 206000 65 sgcarmart 206000 66 singtel 205000 67 cnn 198000 68 google maps 198000 69 posb 193000 70 taobao 192000 71 twitter 192000 72 xvideo 192000 73 ocbc ibanking 191000 74 xhamster2 189000 75 news -

Social Media and Elections in Asia-Pacific - the Growing Power of the Youth Vote

SOCIAL MEDIA AND ELECTIONS IN ASIA-PACIFIC - THE GROWING POWER OF THE YOUTH VOTE EDITED BY ALASTAIR CARTHEW AND SIMON WINKELMANN Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Singapore Media Programme Asia Social Media and Elections in Asia-Pacific - The Growing Power of the Youth Vote Edited by Alastair Carthew and Simon Winkelmann Copyright © 2013 by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 Tel: +65 6603 6181 Fax: +65 6603 6180 Email: [email protected] www.kas.de/medien-asien/en/ facebook.com/media.programme.asia All rights reserved Requests for review copies and other enquiries concerning this publication are to be sent to the publisher. The responsibility for facts, opinions and cross references to external sources in this publication rests exclusively with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Layout and Design page21 7 Kallang Place #04-02 Singapore 339153 CONTENTS FOREWORD PAGE 7 USE OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN POLITICS BY PAGE 13 YOUNG PEOPLE IN AUSTRALASIA by Stephen Mills DIGITAL ELECTIONEERING AND POLITICAL PAGE 29 PARTICIPATION: ‘WHAT’S WRONG WITH JAPAN?’ by Norman Abjorensen SOCIAL NETWORKING SERVICES AND PAGE 45 KOREAN ELECTIONS by Park Han-na and Yoon Min-sik SPRING OF CIVIL PARTICIPATION PAGE 61 by Alan Fong SOCIAL MEDIA AND THE 2013 PAGE 73 PHILIPPINE SENATORIAL ELECTIONS by Vladymir Joseph Licudine and Christian Michael Entoma SOCIAL MEDIA UTILIZATION IN THE PAGE 87 2013 MALAYSIAN GENERAL -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

The Role of the Internet in Singapore's 2011 Elections

series A Buzz in Cyberspace, But No Net-Revolution The Role of the Internet in Singapore’s 2011 Elections By Kai Portmann 2011 © 2011 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Published by fesmedia Asia Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Hiroshimastrasse 28 10874 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49-30-26935-7403 Email: [email protected] All rights reserved. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Friedrich-Ebert- Stiftung or fesmedia Asia. fesmedia Asia does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. ISBN: 978-99916-864-9-3 fesmedia Asia fesmedia Asia is the media project of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) in Asia. We are working towards a political, legal and regulatory framework for the media which follows international Human Rights law and other international or regional standards as regards to Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom. FES in Asia The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung has been working in Asia for more than 40 years. With offices in 13 Asian countries, FES is supporting the process of self-determination democratisation and social development in cooperation with local partners in politics and society. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung is a non-governmental and non-profit making Political Foundation based in almost 90 countries throughout the world. Established in 1925, it carries the name of Germany’s first democratically elected president, Friedrich Ebert, and, continuing his legacy, promotes freedom, solidarity and social democracy. A Buzz in Cyberspace, But No Net-Revolution The Role of the Internet in Singapore’s 2011 Elections By Kai Portmann 2011 Content ABSTRACT 5 1. -

Ts Ge Whitepaper

Through The Social Lens: General Elections 2020 Real Time Real Information OVERVIEW PERSONALITIES Which politicians are gaining the most attention on social media? POLITICAL PARTIES What are the top five political parties people are talking about? ATTRIBUTES ASSOCIATION Which attributes are each political party associated with? CHANNELS Where are the conversations happening? Disclaimer: This publication does not reflect any political opinions of T r u e s c o p e . Data coverage is based upon the online and social channels in SG since 15 June 2020 (updated as of 24 June 2020) PERSONALITIES Which politicians are getting the most attention on social media? PAP Opposition • PM Lee’s announcement of GE [1][2] • Dispute between Pritam Singh, Alfian Sa’at by • Leong Sze Hian Lawsuit [1][2] Dr Tan Wu Meng [1][2] • Pritam Singh’s response to criticism [1] • DPM Heng speaks on 'Emerging • CSJ to not lead a GRC and contest in Bukit Batok Stronger Together’ [1][2] SMC [1][2] • CSJ did not congratulate Paul Tambyah’s new appointment [1][2] • Tan Wu Meng’s criticism of Pritam • Paul Tambyah to lead International Society of Singh’s support of Alfian Sa’at [1][2] Infectious Diseases [1][2] • Paul Tambyah’s response to Singaporean’s not wanting to take up “dirty jobs” [1] • Minister Chan announcing paycuts for senior civil servants [1][2] • PSP to enter 3-cornered fight in West Coast • Minister Chan’s national broadcast [1][2] GRC [1][2] • Thread discussing YouTube Videos by PSP [1] • Minister Teo’s statement of the ‘full effects' • Workers' Party said -

The Singapore Opposition: “Credibility” – the Primary Impediment to Coalition Building

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School – Distinction Theses Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public (Undergraduate) Affairs Spring 2014 The Singapore Opposition: “Credibility” – The Primary Impediment to Coalition Building Brian Steinberg [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/distinction Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Steinberg, Brian, "The Singapore Opposition: “Credibility” – The Primary Impediment to Coalition Building" (2014). Maxwell School – Distinction Theses (Undergraduate). 4. https://surface.syr.edu/distinction/4 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell School – Distinction Theses (Undergraduate) by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Singapore Opposition: “Credibility” – The Primary Impediment to Coalition Building A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Brian Steinberg Candidate for B.A. Degree and Renée Crown University Honors May 2014 Honors Capstone Project in Political Science Capstone Project Advisor: _______________________ Professor Jonathan Hanson Capstone Project Reader: _______________________ Professor Mathew Cleary Honors Director: _______________________ Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: 5/1/2014 Abstract This thesis studies opposition party behavior in competitive authoritarian regimes using the Singapore 2011 general election as a case study. The study asks, what is the primary reason Worker’s Party, the strongest opposition party in Singapore, did not pursue the formation of a pre-electoral coalition? I analyzed the pre-existing theories and conducted fieldwork, interviewing opposition party leaders, academics and activists, to ascertain a direct impediment and not just a background condition to coalition building. -

Social Democratic Parties in Southeast Asia - Chances and Limits

Social Democratic Parties in Southeast Asia - Chances and Limits Norbert von Hofmann*, Consultant, Januar 2009 1. Introduction The people of Southeast Asia, both masses and elites alike, looked for many years foremost up to the United States of America (US) as a role model state. However, the war on terrorism waged by the current US administration linked with cuts in civil liberties and human rights violations, especially the illegal detention and torture of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, has in the eyes of many Southeast Asians considerably discredited the US concept of liberal democracy. Furthermore, the US propagated classical economic liberalism has failed to deliver the most basic human necessities to the poor, and the current food and energy crisis as well as the latest bank crisis in the US prove that neo-liberalism is itself in trouble. The result of neo-liberalism, dominated by trade and financial liberalization, has been one of deepening inequality, also and especially in the emerging economies of Southeast Asia. Falling poverty in one community, or one country or region, is corresponding with deepening poverty elsewhere. The solution can therefore not be more liberalization, but rather more thought and more policy space for countries to pursue alternative options such as “Social Democracy”. The sudden call even from the most hard-core liberals for more regulations and interventions by the state in the financial markets and the disgust and anger of working people everywhere as their taxes being used to bail out those whose greed, irresponsibility and abuses have brought the world’s financial markets to the brink of collapse, proof that the era of “turbo-capitalism” is over. -

Polling Scorecard

Kebun Baru SMC Yio Chu Kang SMC Sembawang GRC Marymount SMC Pulau Punggol West SMC Seletar Pasir Ris- Polling Sengkang GRC Punggol GRC Pulau Tekong Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Pulau Ubin Pulau Serangoon scorecard Chua Chu Kang GRC Holland- Ang Mo Kio Bukit Panjang Bukit Timah GRC SMC GRC Hong Kah Here’s your guide to the polls. Bukit North SMC Aljunied Tampines Batok GRC GRC You can ll in the results SMC as they are released tonight on Bishan-Toa East Coast Pioneer Payoh GRC GRC str.sg/GE2020-results SMC West Coast GRC Jalan Marine Tanjong Besar Parade Pagar GRC GRC GRC Hougang SMC Mountbatten SMC MacPherson SMC Pulau Brani Jurong Yuhua Jurong Potong Pasir SMC Island SMC GRC 5-member GRCs Radin Mas SMC Sentosa 4-member GRCs Single-member constituencies (SMCs) New GROUP REPRESENTATION CONSTITUENCIES Aljunied 151,007 Ang Mo Kio 185,465 Votes cast Spoilt votes voters Votes cast Spoilt votes voters WP No. of votes: PAP No. of votes: Pritam Singh, 43 Sylvia Lim, 55 Faisal Manap, 45 Gerald Giam, 42 Leon Perera, 49 Lee Hsien Loong, Gan Thiam Poh, 56 Darryl David, 49 Ng Ling Ling, 48 Nadia Samdin, 30 68 PAP No. of votes: RP No. of votes: Victor Lye, 58 Alex Yeo, 41 Shamsul Kamar, Chan Hui Yuh, 44 Chua Eng Leong, Kenneth Andy Zhu, 37 Darren Soh, 52 Noraini Yunus, 52 Charles Yeo, 30 48 49 Jeyaretnam, 61 • Aljunied GRC was won by the WP in 2011, making it the rst GE2015 result: • Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong made his 1984 electoral debut in Teck Ghee GE2015 result: opposition-held GRC. -

Press Release Total Votes Cast for General Election

PRESS RELEASE TOTAL VOTES CAST FOR GENERAL ELECTION 2011 Polling Day for General Election 2011 was 7 May 2011 in Singapore. The total number of votes cast in Singapore was 2,057,690 (inclusive of 44,714 rejected votes). Overseas voting was conducted at nine overseas polling stations and the overseas votes were counted on 11 May 2011 at the counting centre at ITE College Central (Balestier). There were 3,453 registered overseas electors from the 26 contested constituencies, out of which, 2,683 turned up to cast their votes. The total number of votes cast for General Election 2011 (i.e. local and overseas votes) is 2,060,373 (inclusive of 44,737 rejected votes). This is 93.18% of the 2,211,102 registered electors in all contested electoral divisions. (See Annex for breakdown by electoral divisions). ISSUED BY: ELECTIONS DEPARTMENT 11 MAY 2011 ANNEX Votes cast for General Election 2011 (by Electoral Divison) *Local and overseas votes *VALID VOTES CAST VALID VOTES CAST (Number) (%) People’s Action Party 59,829 45.28% ALJUNIED Workers’ Party 72,289 54.72% People’s Action Party ANG MO KIO 112,677 69.33% Reform Party 49,851 30.67% People’s Action Party 62,385 56.93% BISHAN-TOA Singapore PAYOH People’s Party 47,205 43.07% People’s Action Party 20,375 66.27% BUKIT PANJANG Singapore Democratic Party 10,372 33.73% National Solidarity CHUA CHU Party 56,885 38.80% KANG People’s Action Party 89,710 61.20% People’s Action Party 59,992 54.83% EAST COAST Workers’ Party 49,429 45.17% People’s Action Party 48,773 60.08% HOLLAND- Singapore BUKIT TIMAH Democratic