Investigation Into University Technical Colleges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cepals 12 Free Schools and Freedoms

CEPaLS 12: Are Free schools really about freedom? Helen M Gunter University of Manchester This text was original posted on my Tumblr Blog on 15th January 2017. This Blog has now been deleted and so I am presenting it as a CEPaLS paper. The Campaign for State Education (CASE) has reported a list of 21 ‘free’ schools or ‘studio’ schools which have been given taxpayer funding but are now closed. I am going to list them here as this will make it real: Black Country UTC Walsall. Walsall Closed University Technical College. Bradford Studio School Bradford. Bradford Closed Studio Schools. Central Bedfordshire UTC Central Bedfordshire. Houghton Regis Closed University Technical College. Create Studio East Riding of Yorkshire. Goole Closed Studio Schools. Dawes Lane Academy North Lincolnshire. Scunthorpe Closed Free Schools. Discovery New School West Sussex. Crawley Closed Free Schools. The Durham Free School Durham. Durham Closed Free Schools. Hackney University Technical College Hackney. London Closed University Technical College. Harpenden Free School Hertfordshire. Harpenden Closed Free Schools. Hartsbrook E-Act Free School. Haringey Closed Free Schools. Hull Studio School Kingston upon Hull. City of Hull Closed Studio Schools. Hyndburn Studio School Lancashire. Accrington Closed Studio Schools. Inspire Enterprise Academy Southampton. Southampton Closed Studio Schools. Kajans Hospitality & Catering Studio College - KHCSC Birmingham. Birmingham Closed Studio Schools. The Midland Studio College Hinckley Leicestershire. Hinckley Closed Studio Schools. The Midland Studio College Nuneaton Warwickshire. Nuneaton Closed Studio Schools. New Campus Basildon Studio School Essex. Basildon Closed Studio Schools. Royal Greenwich Trust School Academy Greenwich. London Closed Free Schools. St Michael's Secondary School Cornwall. -

School Admissions September 2020

School admissions September 2020 School year Children born between Reception 1 September 2015 and 31 August 2016 Infant and junior transfer 1 September 2012 and 31 August 2013 Year 7 1 September 2008 and 31 August 2009 Year 10 transfer 1 September 2005 and 31 August 2006 www.hillingdon.gov.uk/schooladmissions Foreword Dear parent/carer selection of studio schools and new university Starting a new school is a big milestone for you technical colleges. These establishments still and your child. In Hillingdon, we are committed offer traditional subjects, such as Maths, to ensuring every child has a high quality school English and Science GCSE courses, but are also place as close to home as possible. If your child able to offer additional vocational subjects, as a is due to start primary or secondary school in result of having a longer school day. September 2020, this brochure will help you Our School Placement and Admissions team make an informed choice when deciding which coordinates applications for Hillingdon school is right for your child. residents with all of the other 32 London Hillingdon Council has successfully led the boroughs, as part of the pan-London opening of brand new, modern schools in the coordinated admissions system. The team borough, as well as expanding existing schools works hard to ensure that, as far as possible, on time to ensure there are enough school you are offered your highest-preference places for Hillingdon’s residents. secondary school in London. Like many other At the primary stage, Hillingdon has a range of parts of London, Hillingdon experiences a high schools, including academies, faith and free demand for school places. -

Strategic Economic Plan

Made in the Black Country: Sold Around the World Black Country Strategic Economic Plan ‘Made in the Black Country: Sold around the World’ 31st March 2014 1 Made in the Black Country: Sold Around the World 2 Made in the Black Country: Sold Around the World EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1 THE BLACK COUNTRY STRATEGIC ECONOMIC PLAN .............................................................................................................. 10 1.1 A GUIDE TO THE BLACK COUNTRY STRATEGIC ECONOMIC PLAN ............................................................................................................ 10 1.2 THE BLACK COUNTRY STRATEGIC ECONOMIC PLAN ............................................................................................................................ 11 1.3 THE BLACK COUNTRY – OUR OPPORTUNITY ..................................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 THE BLACK COUNTRY IN 2033 – OUR OVERARCHING LONG TERM STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK ...................................................................... 12 2 OUR GROWTH STRATEGY ..................................................................................................................................................... 14 2.1 OUR STRATEGIC PROGRAMMES .................................................................................................................................................... -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Ron Dearing UTC - Impact Assessment

Ron Dearing UTC - Impact Assessment Secondary Schools Number of Number of Distance School KS4 surplus surplus Inspection Inspection Impact School name Type from UTC capacity Attainment places (May places in year rating date Rating (miles) (May 2014) 2015 2014) 10 (Jan 2015) Hull Trinity House Academy Academy Converter 0.1 600 203 65 66% Good 15-Feb-2012 Moderate The Boulevard Free Schools 1.5 600 461 120 No KS4 data Outstanding 14-May-2015 Moderate Academy Malet Lambert Academy 2.1 1535 81 3 60% Good 26-Apr-2012 Moderate Converter Newland School Community 2.2 750 48 41 47% Requires 18-Sep-2014 Moderate for Girls School Improvement St Mary's College Voluntary Aided 2.2 1550 -186 -20 78% Outstanding 8-Jul-2010 Minimal School Kelvin Hall School Foundation 2.3 1463 99 24 67% Outstanding 4-Feb-2015 Minimal School Archbishop Academy 2.5 1550 121 27 16% Good 6-Feb-2014 Moderate Sentamu Academy Sponsor Led Winifred Holtby Academy 2.5 1350 38 11 42% Requires 25-Mar-2015 Moderate Academy Converter Improvement Thomas Ferens Academy 2.8 1250 589 146 44% Inadequate 18-Jun-2014 High Academy Sponsor Led Sirius Academy Academy 3.0 1650 114 -6 42% Outstanding 14-Mar-2014 Minimal Sponsor Led Kingswood Academy 3.5 900 312 101 32% Inadequate 21-Jan-2015 High Academy Sponsor Led Andrew Marvell Foundation 3.6 1325 439 69 48% Inadequate 27-Nov-2013 High College School Wolfreton School Community and Sixth Form School 4.5 2096 592 11 66% Good 24-Oct-2013 Moderate College Cottingham High Academy Requires School and Sixth 4.8 1415 315 39 47% 7-May-2015 High Converter Improvement Form College Hessle High Academy School and Sixth Converter 5.0 1503 264 34 64% Good 11-Dec-2014 Moderate Form College Summary Within the local area of the proposed UTC, it is expected that 4 schools may feel a high impact, 8 schools may feel a moderate impact and 3 schools may feel a minimal impact. -

University Technical Colleges

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07250, 27 July 2020 By Robert Long, Shadi University Technical Danechi, Nerys Roberts, Philip Loft Colleges Inside: 1. The development and role of UTCs 2. Expenditure and Financial Position of UTCs 3. Pupil Profile 4. UTCs: Performance and Ofsted Reports 5. Commentary on UTCs 6. Policy Developments post- 2015 7. Reports on UTCs www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07250, 27 July 2020 2 Contents Summary Briefing 3 1. The development and role of UTCs 5 1.1 Conception 5 1.2 What are UTCs? 6 1.3 Opening a New UTC 8 1.4 Closure/Conversion of UTCs 11 2. Expenditure and Financial Position of UTCs 14 3. Pupil Profile 18 3.1 Free School Meals 18 3.2 Special Educational Needs 18 3.3 Gender 18 4. UTCs: Performance and Ofsted Reports 20 4.1 Pupil Attendance 20 4.2 GCSE results 21 4.3 Pupil Outcomes: Destinations 21 4.4 Ofsted Reports 22 5. Commentary on UTCs 23 6. Policy Developments post-2015 26 6.1 2015 Pause in UTC Programme 26 6.2 Requirement to inform parents 26 6.3 ‘Baker Clause’ 26 6.4 Membership of Multi-Academy Trusts 28 6.5 Impact of EBacc 29 6.6 Introduction of T-Levels 30 7. Reports on UTCs 31 7.1 Public Accounts Committee (2020) 31 7.2 NAO Report (2019) 32 7.3 Education Policy Institute (2018) 33 7.4 IPPR (2017) 34 7.5 NFER Report (2017) 36 Cover page image copyright: Laboratory by biologycorner. -

A Guide to Secondary School Admissions 2022-2022

A Guide to Secondary School Admissions 2022-2022 . HULL CITY COUNCIL Dear Parent/Guardian Starting school is a big step in your child’s life. This booklet should help make this as easy as possible by providing all of the information that you should need to help you through this process. If you live in Hull and your child is due to transfer to secondary school in September 2022 you need to have made your application by 31 October 2021. You can do this by applying online: go to www.hull.gov.uk/admissions Please read this booklet carefully and in particular, take note of the admissions criteria for the schools that you are interested in. For more detailed information about individual schools, you can contact them directly. They will welcome your enquiries and be happy to supply information about curriculum details, school uniforms, examination results and other areas of interest. Offers of primary school places will be made on 1 March 2022. If you need more information or help to use the online service, please contact the admissions team on (01482) 300 300, take a look at the information about admissions on the Council’s website: www.hull.gov.uk/admissions or call into one of the Council’s customer service centres or any Hull library. We are committed to ensuring that all children in Hull are given opportunities to achieve their potential. Starting at primary school for the first time is a key step in this journey. I hope that you find the information in this booklet helps you through the school admissions application process to achieve this as easily as possible. -

Investing in the True North Hull City Centre Delivery and Investment Plan 2018-2023

INVESTING IN THE TRUE NORTH HULL CITY CENTRE DELIVERY AND INVESTMENT PLAN 2018-2023 Introduction and purpose 1. Hull city centre is changing; it was, and is, at the City’s heart where people live, work, shop, socialise. While recent investment has radically improved the overall quality of place, connectivity and visitor experience, the trends now shaping all city centres are continuing to impact on Hull’s vibrancy and sustainability. In facing these impacts we need to work smarter. A plan is needed to understand, and enable, the form and location of investment needed to ‘right-size’ the city as part of a resurgent True North part of the UK. 2. In the UK the growth of the digital revolution and its impact on retail means that the sector has become less of a main driver of city centre economies. In order to compete and thrive, city centres need to be much more than retail destinations. They need to be places that people will visit because of their overall quality of experience, liveability and increasingly because of the range of opportunities they offer, for leisure, dining and culture. Retail is just one, but an important part of the mix, with an ongoing trend towards something more distinctive and unique. 3. Changing consumer needs and demands, including the loss of spending power to out-of-centre shopping destinations, having impacted on the performance of the UK high street retail over the past 10 – 15 years. Exacerbated by the 2008 recession, these changes have had a dramatic impact on the role and performance of city centres, perhaps more so in the marginal centres of the North of England. -

Hull 2030 Carbon Neutral Strategy

Carbon Neutral Hull An Environment and Climate Change Strategy for 2020 - 2030 1-V14-FINAL Carbon Neutral Hull Framework Chart 1: Carbon Neutral Hull Framework 2-V14-FINAL Contents: Executive Summary 4 Leadership 7 Place 9 The Approach 12 The Challenge Ahead 14 Energy: Heat 27 Energy: Power 30 Mobility 33 Consumption 36 Innovation 39 Skills and Jobs 42 Fair Transition 45 Carbon Sequestration 48 Glossary 51 Appendix 1 Hull Peoples Panel June 2019 Climate Change Infographic 52 Appendix 2 United Nations Sustainable Development Gaols 53 3-V14-FINAL Executive Summary The decision by the Council to declare a climate emergency in March 2019 is a significant point in the history and is the point at which Hull made its commitment to carbon neutrality which will be the key force shaping its future over the next ten years and beyond. A Hull Peoples Panel survey in June 2019 found that 68% of residents agree that there is a climate emergency and 77% of residents think that climate change is a threat. Addressing climate change is therefore a key issue for our residents. Our vision is for Hull to become a leading carbon neutral city within the United Kingdom (UK) by 2030, to have taken all possible action, under its control, to reduce emissions so that Hull becomes fully carbon neutral by 2030. The achievement of carbon neutrality by Hull for 2030 is a big challenge, and one that requires significant policy and funding change that can only be delivered by Government. Therefore, based upon the national net zero target for 2050, established within the Climate Change Act, and the current policy and funding landscape, Hull will aim for a minimum carbon reduction of 77% by 2030 from its 2005 carbon emissions1. -

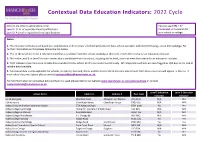

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

John Dickens a Front Line Visit to the Somme

david lundie John dickens finnish discussing A front line lessons? extremism visit to the There’s not in class somme much to learn Page 19 Page 9 Page 18 SCHOOLSWEEK.CO.UK FRIDAY, APRIL , | EDITION MANIFESTOS: WHAT THEY SAY ABOUT SCHOOLS Pages 6 & 7 Exam overhauls ‘force’ Cambridge to plan entry tests University consults on bringing back own entrance test after 29 years P 14 ‘What I hear is a lot more work for me. It makes me really frustrated’ Documents presented at a senior tutors’ committee Debra Kidd: If I were JOHN DICKENS (STC) in March, seen by Schools Week, state that @JOHNDICKENSSW Exclusive the university is “being forced” into changing its education secretary ... “well-tried system” of using AS-levels to assess which The University of Cambridge is gathering views on applicants get invited for interview. plans to bring back entrance tests – 29 years after The paper says that GCSEs “will not give us a I would consider what teachers abandoning them. reliable measure” due to their ongoing reform and If the proposal goes ahead, all school pupils applying need to do their job well to the university would need to sit the test. Continued on page 2 BUILD A BETTER SUPPLEMENT IN PARTNERSHIP WITH baccalaureate PRODUCED BY SUPPLEMENT FREE WITH THIS ISSUE 2 @SCHOOLSWEEK SCHOOLS WEEK FRIDAY, APRIL 17, 2015 EDITION 25 NEWS Cambridge rethinks admissions process SCHOOLS WEEK TEAM JOHN DICKENS CONTINUED Editor: Laura McInerney @JOHNDICKENSSW FROM FRONT Head designer: Nicky Phillips that “schools’ predictions of grades will be Designer: Rob Galt next to useless”. Sub editor: Jill Craven University departments have now been asked for their views on a “main proposal” to Senior reporter: Sophie Scott reintroduce tests from the 2016-17 admissions Senior reporter: Ann McGauran round. -

University Technical Colleges in London (Schools for 14–19 Year Olds)

University Technical Colleges in London (schools for 14–19 year olds) Name and address Date of Opening Specialism Contact Details Local Authority Area (LA web address) How to apply Elutec (East London University Website: Barking & Dagenham Technical College) www.elutec.co.uk/ Borough Council Address: September Email: Yew Tree Avenue, 2014 Product design [email protected] www.lbbd.gov.uk/admissions Direct to the school Rainham Road South, Dagenham East Telephone: RM10 7FN 020 3773 4670 Global Academy UTC Website: Hillingdon Borough www.globalacademy.com/ Council Address: The Old Vinyl Factory, September Creative, technical and Email: Blyth Road, 2016 broadcast and digital [email protected] Direct to the school Hayes, media www.hillingdon.gov.uk/schooladmissions Middlesex Telephone: UB3 1DH 020 3019 9000 UTC Heathrow Website: Hillingdon Borough Council Address: www.heathrow-utc.org/ Potter Street, Northwood, September Aviation engineering Email: www.hillingdon.gov.uk/schooladmissions Middlesex 2014 Engineering [email protected] Direct to the school HA6 1QG Telephone: 019 2360 2130 London Design and Engineering Website: Newham Borough Council UTC (LDEUTC) www.ldeutc.co.uk/ www.newham.gov.uk/Pages/Category/Schools-and- Address: Email: colleges.aspx?l1=100005 Docklands Campus, September Design [email protected] University Way, 2016 Engineering Direct to the school London Telephone: E16 2RD 07714 255 193 University Technical Colleges in London (schools for 14–19 year olds) Name and address Date of Opening Specialism