Growth on the Gold Line: Evaluating the Foothill Extension and the Potential of Transit-Oriented Development Adam E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claremont Traffic and Transportation Commission

CLAREMONT TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION MEETING AGENDA “We are a vibrant, livable, and inclusive community dedicated to quality services, safety, financial strength, sustainability, preservation, and progress with equal representation for our community.” City Council Chamber Thursday 225 Second Street July 22, 2021 Claremont, CA 91711 7:00 PM COMMISSIONERS JUSTINE GARCIA CHAIR JACK BLAIR GLORIA HERNANDEZ-LOOFBOURROW JOHN MARLER JULIE MEDERO BRIAN MCCABE SONJA STUMP Pursuant to the local emergency concerning the COVID-19 virus declared by the City Council of the City of Claremont on March 19, 2020, the Los Angeles County Department of Health’s “Safer at Home Order” issued March 19, 2020, and Executive Order N-29-20 issued by Governor Gavin Newsom on March 18, 2020, the following protocols will apply to public participation for the duration of the emergency: Members of the public will not be permitted to be physically present at meetings. To allow for public participation, the Traffic and Transportation Commission will conduct its meeting through Zoom Video Communications. To participate in the meeting from the comfort of your own home or office, download Zoom on any phone or computer device and copy and paste the following link into your web browser to access and participate in the live Commission meeting at 7:00 p.m.: https://zoom.us/j/97473747561 or to only listen from the phone dial (213)338-8477, Web ID: 974 7374 7561. Members of the public who wish to address the Traffic and Transportation Commission on any matter listed on the agenda or a subject matter within the jurisdiction of the Commission may utilize the following methods. -

January–June 2005 · $10.00 / Rails To

January–June 2005 · $10.00 / Rails to Rubber to Rails Again, Part 1: Alabama–Montana Headlights The Magazine of Electric Railways Published since 1939 by the Electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc. WWW.ERAUSA.ORG Staff Contents Editor and Art Director January–June 2005 Sandy Campbell Associate Editors Raymond R. Berger, Frank S. Miklos, John Pappas Contributors Edward Ridolph, Trevor Logan, Bill Volkmer, Columns Alan K. Weeks 2 News Electric Railroaders’ Compiled by Frank Miklos. International transportation reports. Association, Inc. E Two-Part Cover Story Board of Directors 2008 President 18 Rails to Rubber to Rails Again Frank S. Miklos By Edward Ridolph. An extensive 60-year summary of the street railway industry in First Vice President the U.S. and Canada, starting with its precipitous 30-year, post-World War II decline. William K. Guild It continues with the industry’s rebirth under the banner of “light rail” in the early Second Vice President & Corresponding Secretary 1980s, a renaissance which continues to this day. Raymond R. Berger Third Vice President & Recording Secretary Robert J. Newhouser Below: LAMTA P3 3156 is eastbound across the First Street bridge over the Los Treasurer Angeles River in the waning weeks of service before abandonment of Los Angeles’ Michael Glikin narrow gauge system on March 31, 1963. GERALD SQUIER PHOTO Director Jeffrey Erlitz Membership Secretary Sandy Campbell Officers 2008 Trip & Convention Chairman Jack May Librarian William K. Guild Manager of Publication Sales Raymond R. Berger Overseas Liason Officer James Mattina National Headquarters Grand Central Terminal, New York City A-Tower, Room 4A Mailing Address P.O. -

Reapportionment of Legislative Districts

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Propositions California Ballot Propositions and Initiatives 1928 REAPPORTIONMENT OF LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/ca_ballot_props Recommended Citation REAPPORTIONMENT OF LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS California Proposition 1 (1928). http://repository.uchastings.edu/ca_ballot_props/230 This Proposition is brought to you for free and open access by the California Ballot Propositions and Initiatives at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Propositions by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , i, , , REAPPOfiTIONMENT OF LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS. Act of Legisla- I , latu.t~ submitted to electors by referendum. Amends'Section 78 and t~'\I YES ' ... repeals ~ection 90 of Political Code. Reapportions the legislative dis- , I I- tricts of the state, defining and establishing. such districts, under I authority of Section 6 of Article IV of Constitution adopted November I NO 2, 19Z6r I (For ~II text of Measure see page 1, Part II) Argument In Favor of Reapportionment of interests of this great commonwealth: The act Legislative Districts Referendum Measure is a just, conscientious and carefully framed law. A vote ,"'yes" will sustain the law-the so- It deserves to be sustained. Vote yes on Pl'OPO- called vl\OggS Reapportionment A,ct"--enacted sition Number One on the ballot. " , by the state legislature in 19"27 by DNANI- J. M. INMAN, MOUS VOTE. The law' was enacted in obedi- State Senator, Seventp. District. ence to the mandate of the voters, who, at the gelleral election of 1926, adopted the Federal FRANK S. -

Table of Contents Agenda 3 CC 1. City Council to Approve Minutes Of

Table of Contents Agenda 3 CC 1. City Council to approve minutes of the September 15, 2015 Regular meeting of the City Council/Successor Agency to the Covina Redevelopment Agency/Public Finance Authority/Housing Authority. Minutes of September 15, 2015 9 CC 2. City Council to approve the payment of demands in the amount of $3,288,615.54. Payment of Demands 19 CC 3. Successor Agency to the Redevelopment Agency to approve payment of demands in the amount of $13,513.11. Payment of Demands 29 CC 4. City Council to approve Change Orders for Pedestrian and Metrolink Station Improvements. Resolution No. 15-7397 33 CC 5. City Council to consider agreement with Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority for MTA Transit- Oriented Development Planning Grant. LACMTA Agreement 55 CC 6. City Council to approve Change Orders for Glendora Avenue and Cienega Street Traffic Signal Installation. Resolution No. 15-7402 103 CC 7. City Council to approve Final Acceptance and filing of Notice of Completion for Resurfacing of Streets at Hollenbeck Avenue, Cypress Street, et al. Resolution No. 15-7403 113 CC 8. City Council to authorize Second Amendment to Absolute Security International Agreement for security services at Covina Metrolink Station and Parking Complex. Resolution No. 15-7404 123 CC 9. City Council to confirm the continued existence of an emergency condition for Roycove Reservoir and Pump Station. Resolution No. 15-7405 157 CC 10. City Council to amend Fiscal Year 2015-16 Parks and Recreation Department, Library Services Division Budget by $19,500 for the purchase of books and periodicals utilizing the Joseph J. -

1981 Caltrans Inventory of Pacific Electric Routes

1981 Inventory of PACIFIC ELECTRIC ROUTES I J..,. I ~ " HE 5428 . red by I58 ANGELES - DISTRICT 7 - PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION BRANCH rI P37 c.2 " ' archive 1981 INVENTORY OF PACIFIC ELECTRIC ROUTES • PREPARED BY CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION (CALTRANS) DISTRICT 07 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION BRANCH FEBRUARY 1982 • TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Pacific Electric Railway Company Map 3a Inventory Map 3b II. NQR'I'HIRN AND EASTERN DISTRICTS 4 A. San Bernardino Line 6 B. Monrovia-Glendora Line 14 C. Alhambra-San Gabriel Line 19 D. Pasadena Short Line 21 E. Pasadena Oak Knoll Line 23 F. Sierra Madre Line 25 G. South Pasadena Line 27 H. North Lake Avenue Line 30 10 North Fair Oaks Avenue Line 31 J. East Colorado Street Line 32 K. Pomona-Upland Line 34 L. San Bernardino-Riverside Line 36 M. Riverside-Corona Line 41 III. WESTERN DISTRICT 45 A. Glendale-Burbank Line 47 B. Hollywood Line Segment via Hill Street 52 C. South Hollywood-Sherman Line 55 D. Subway Hollywood Line 58 i TABLE OF CONTENTS (Contd. ) -PAGE III. WESTERN DISTRICT (Conta. ) E. San Fernando valley Line 61 F. Hollywood-Venice Line 68 o. Venice Short Line 71 H. Santa Monica via Sawtelle Line 76 I. westgate Line 80 J. Santa Monica Air Line 84 K. Soldier's Home Branch Line 93 L. Redondo Beach-Del Rey Line 96 M. Inglewood Line 102 IV. SOUTHIRN DISTRICT 106 A. Long Beach Line 108 B. American Avenue-North Long Beach Line 116 c. Newport-Balboa Line 118 D. E1 Segundo Line 123 E. San Pedro via Dominguez Line 129 F. -

TIMEPOINTS Volume 89 January/February/March 1996 Numbers 1, 2 & 3

TIMEPOINTS Volume 89 January/February/March 1996 Numbers 1, 2 & 3 Angels Flight™ Re-opens JANUARY/FEBRUARY/MARCH 1996 Page 1 ™ Timepoints January/February/March 1996 Angels Flight Reopens The Southern California Traction Review On February 23, 1996 at approximately 9:37am the offi- cial first run of the restored version of Angels Flight™ Always a Newsletter in sight produced by ended almost 27 years of “Flightless” activity between Hill The Electric Railway Historical Association & Olive Streets in downtown Los Angeles. of Southern California, Inc. TIMEPOINTS has already brought you extensive coverage Subscription included in membership. of the rebuilding process (see November 1991 issue, mov- ing the winch house and arch to Hill Street, March 1994 ERHA membership is $25.00 per year issue devoted to the restoration, January/February/March Editorial Mailing Address Circulation, ERHA Business 1995 issue, construction begins and July/August/Septem- Digital Realitites ERHA of SC ber 1995 Olivet & Sinai and more construction progress) John Heller 1 World Trade Center but the reopening of the Flight means much to Angelenos 7315 Melrose Avenue P.O. Box 32161 and is the closest thing to heritage trolley operation we Hollywood, CA 90046 Long Beach, CA 90832-2161 have... ERHA of SC1995 Board of Directors Service hours are President Alan Fishel 6AM to 10PM seven days/ Vice-President John Heller week (original hours Recording Secretary Jerry Pass were 6AM to 12:20AM Treasurer Jed Hughes seven day/week) Membership Secretary William Costley Restoration cost: $4.1 At-Large David Cameron million Paul Ward Funding: CRA and ÇPershing Square Red LineStation Contributors . -

Public Utilities Commission Records. Part II

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2v19n5dh No online items Inventory of the Public Utilities Commission Records. Part II Processed by The California State Archives staff; supplementary encoding and revision supplied by Xiuzhi Zhou. California State Archives 1020 "O" Street Sacramento, California 95814 Phone: (916) 653-2246 Fax: (916) 653-7363 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/ © 2000 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Public Utilities F3725 1 Commission Records. Part II Inventory of the Public Utilities Commission Records. Part II Inventory: F3725 California State Archives Office of the Secretary of State Sacramento, California Contact Information: California State Archives 1020 "O" Street Sacramento, California 95814 Phone: (916) 653-2246 Fax: (916) 653-7363 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/ Processed by: The California State Archives staff © 2000 California Secretary of State. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Public Utilities Commission Records. Part II Inventory: F3725 Creator: Public Utilities Commission Extent: see Arrangement and Description Repository: California State Archives Sacramento, California Language: English. Publication Rights For permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the California State Archives. Permission for reproduction or publication is given on behalf of the California State Archives as the owner of the physical items. The researcher assumes all responsibility for possible infringement which may arise from reproduction or publication of materials from the California State Archives collections. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Public Utilities Commission Records. Part II, F3725, California State Archives. Folder (F3725:6522-9318)1. Formal Applications. 1914 - 1952. -

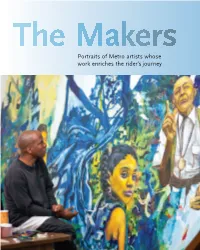

Portraits of Metro Artists Whose Work Enriches the Rider's Journey

The Makers Portraits of Metro artists whose work enriches the rider’s journey The Makers Portraits of Metro artists whose work enriches the rider’s journey Summer 2016 to Winter 2017 Union Station Passageway This exhibition is presented by Metro Art in collaboration with artist Todd Gray. Cover: Portrait of Michael Massenburg by Todd Gray. Opposite: Detail of MacArthur Park, Urban Oasis (2010) by Sonia Romero, Westlake/MacArthur Park Station. Metro Art is Artworks at Stations Art and artists transform the public transit experience. & Facilities Artworks animate the transitional moments between destinations, elevating the mood, punctuating the Photography Installations transit landscape and transporting the imagination Art Posters of Metro riders. They express the texture, little known narratives and aspirations of our region. Poetry Cards & Readings By integrating artworks into Metro’s myriad transit Music & Dance environments, we enrich the journeys of millions of Participatory Art people each day. & Performance metro.net/art Film Screenings Art Banners Community Engagement Meet-the-Artist Events Artist Workshops Art Tours Creative Placemaking Cultural Partnerships Metro Art is Detail of Long Beach poster (2013) by Christine Nguyen, Through the Eyes of Artists series. The Makers The Makers is an ongoing series of photographic portraits by Todd Gray, featuring the artists behind the artworks in the Metro system. In this initial installation at Union Station, the 30 featured artists span multiple generations, come from a variety of backgrounds, and work in a remarkable range of mediums and styles. Some are emerging artists, while others are more established. The breadth of the group is a testament to the high concentration of creative talent living and working in the Los Angeles region. -

April 2016 Pricing Bene>Ts Charging Costs $1 Per Hour with a $3 Cap Per Charge, Low Price – You Can Charge All Day for Just $3

metro.net/ev Plug in and Go Metro. ev charging fact sheet Overview How it works As a leader in sustainability and clean technology Sign up for an account on metro.net/ev. initiatives, Metro is the first transit agency in 1 the nation to integrate electric vehicle (EV) charge stations at its Park & Ride lots. The Level 2 charge stations allow riders with Download the EV Connect Mobile app, available EVs to conveniently charge their cars while using 2 for iPhone and Android. the Metro system. Park your vehicle at a Metro 3 charge station marked with the parking symbol to the right. Use the app to scan the station’s QR code. Or, touch your key fob on the reader pad 4 to start charging. Key fobs can be purchased from my.evconnect.com. 5 Plug in and Go Metro! april 2016 Pricing Bene>ts Charging costs $1 per hour with a $3 cap per charge, Low Price – You can charge all day for just $3. and users will be billed through their account. Parking is free at all charge stations except at Union Station. Convenience – Your vehicle will be fully charged when you return from your travels. Reduced Greenhouse Gas Emissions – By Locations combining an EV trip with public transit, EV charge stations are located at each of the you’ll further help to reduce our region’s overall following Metro Rail station parking lots: greenhouse gas emissions. > Union Station Expansion to More Stations – In 2016, 801 N Vignes St, Los Angeles 90012 Metro plans to expand its EV charging program Eight charge stations: P2 level (area D and M) as regional demand increases. -

Silver Platinum Silver Platinum

It is the mission of the Irwindale Chamber of Commerce to BUILD solid relationships and provide quality services which SUPPORT chamber members and businesses, in order to PROMOTE the economic vitality of our community. Volume 28, Number 8 August 2008 CORNERSTONES of Irwindale Seizing a Golden Opportunity for Valley Commerce By: Adam B. Schiff, D-Pasadena, represents the 29th Congressional District. If you commute in Los Angeles County, you spend too much time behind the wheel - 72 hours a year too much to be exact. Los Angeles is the most Platinum congested region in the nation, and this costs an average commuter $1374 a year more than others spend for time and gasoline. In fact, the average Southern Californian consumes 57 extra gallons of gas a year stuck in traffi c, and with a Silver gallon of gas approaching $5, this is a crushing burden for many families. Silver With millions of frustrated commuters stuck on our freeways, Los Angeles also has the distinction of having the worst year-round pollution in the country. It is an economic and health imperative that we reduce congestion Bronze on our freeways, cut traffi c and commute times, and decrease smog - and investing in mass transit is a big part of the answer. There is no question that the Gold Line Foothill Extension, which will extend the Gold Line from Pasadena to Azusa and beyond to Ontario Airport, will Corporate be a part of our future - but that future should be now. It will not only give AJL A. J. LONGO & ASSOCIATES )NSURANCEs&INANCIAL3ERVICES people a clean, comfortable and cost-effective way to get to work or school, ROYAL COACHES AUTO BODY & TOWING (Golden Opportunity-continued on page 9) Alexandria Hernandez named Irwindale’s 2008 Business Solution Young Citizen of the Year! Seminar: Preventing Sexual Congratulations to three of Irwindale’s outstanding Harassment teenagers: Alexandria Hernandez, Hannah Fraijo (details on page 13) and Angelica Torres. -

Bike to Metro

metro.net/moregold metro.net metro.net/moregold Go Metro La Extensión Foothill Ventura County Line Metro Gold Line SAN FERNANDO VALLEY S Chatsworth P ¢ P ¢ Nordhoff P ¢ n F o de Metro Gold Line P wood Foothill Extension ¢ P ege P P ¢ l ny ¢ ¢ P l / P P Roscoe ¢ P da n ¢ Antelope Valley Line ¢ P Sherman ¢ e a ¢ v uys m Way l d P eda o ey Co rel Ca ¢ oodley pu o u rth Holly F ampa es an N o P P P ¢ De Soto Pierce CollegeT R Balboa W Se V W Vall La N P ¢ /Highland ¢ P P ¢ P ¢ ¢ ¢ /City of Hope P Downtown Universal City ¢ Citrus Studio Citywood / Vine rn / e anoga olly st FillmoreDel MarMemorialLake Park Allen Sierra MadreArcadia VillaMonroviaDuarte IrwindaleAzusa APU C H e College wood ¢P South Pasadena arner Ctr¢P /W W olly od Highland Park HOLLYWOOD H wo y AZUSA oll Southwest Museum Guía de destinos Arcadia a Azusa H Destination Guide Arcadia to Azusa ¢P Heritage Sq Vermont/Sunset F P ¢ Lincoln/Cypress P P Vermont/Santa Monica ¢ Chinatown San Bernardino Line Civic Center/ El Monte ¡Todos abordo de Vermont/Beverly LAC+USC Medical CtrCal State LA Rediscover Gold on the Metro DOWNTOWN Grand Park ¢P Union Station ¢ Metro Gold Line! KOREATOWN LA EL MONTE Gold Line Foothill Extension! t Little Tokyo/ nt o Pershing Sq ¢P Arts Dist rmo estern e / EAST LOS ANGELES W V Aproveche del servicio directo y conveniente / ormandie / /N 7th St/Metro Ctr Take advantage of the direct and convenient estlake Aliso W / o Wilshire Wilshire entre el Centro de Los Angeles y Azusa. -

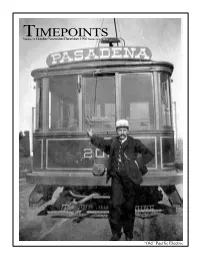

TIMEPOINTS Volume 90 October/November/December 1996 Numbers 4, 5 & 6

TIMEPOINTS Volume 90 October/November/December 1996 Numbers 4, 5 & 6 “Old” Pacific Electric OCTOBER/NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 1996 Page 1 Timepoints October/November/December 1996 Three newBefore Red Line the GreatStations Merger The Southern California Traction Review Pacific Electric circa 1906 Rare is the surviving material on the original California char- Always a Newsletter in sight produced by tered Pacific Electric Railway in comparison to its direct de- The Electric Railway Historical Association scendant; the great and powerful Pacific Electric Railway of of Southern California, Inc. the post 1911 merger. While browsing through the offerings Edited by John Heller at a swap meet, ERHA president Alan Fishel chanced upon a tattered photo album almost 100 years in age. Image his de- ERHA membership is $25.00 per year light upon finding inside mostly trolley photos, specifically ERHA OF SC the “Old” Pacific Electric in and around Pasadena! 1 WORLD TRADE CENTER The unknown camera buff was certainly a PE crew member PO BOX 32161 as well as an early amateur photographer. The prints them- LONG BEACH CA 90832-2161 selves are very small, home printed and are not holding up www.erha.org well with time... but, we have run each of them through the ERHA of SC1996 Board of Directors computer, and ‘tho far from perfect, thanks to Alan’s generos- President Alan Fishel ity in sharing them, we have a special treat for our readers. Vice-President John Heller Equipment and car numbering Recording Secretary Jerry Pass This Pacific Electric came along relatively late amongst the Treasurer Jed Hughes dozens of local streetcar operators and was also the strongest Membership Secretary William Costley financially due in no small part to the large participation of At-Large Ralph Cantos multimillionaire Henry H.